It’s Thanksgiving weekend in the U.S., and I’m giving thanks for the beautiful place I live which I’ve gotten to know better through my 2020 life experiment, The Year of Living Locally.

Case in point, a recent hike our family went on in nearby Santa Clara. My wife Andrea picked out a perfect #LocalYear hike for us at Ulistac Natual Area (UNA). Perfect because I wanted to get to know the land and heritage of my area better during 2020.

According to Ulistac Natural Area Restoration and Educational Project, the local non-profit responsible for the land, UNA is the only dedicated natural open space in the City of Santa Clara.

UNA’s 40 acres of undeveloped land along the Guadalupe River, not far from the largest nearby city, San Jose, is a tiny oasis of natural beauty in a giant suburban desert. It’s also a work in progress as UNA and its many volunteers attempt to return the tract to pre-colonial condition.

As we hiked the area, I started to grok how difficult that’s going to be. Just across the street from the entrance is a sprawling townhouse development. Tall levees straightjacket the river. There’s a large, concrete flood control pump house in the middle of the park. I also noticed several towering eucalyptus trees, an invasive species from a different continent over 7,000 miles away.

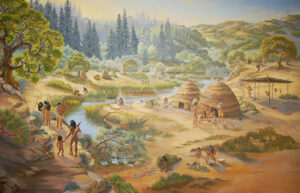

However, the most significant thing about the land isn’t what’s there today — it’s what’s missing, the Ohlone. That’s the name for the various indigenous peoples who tended the land in the area for up to 3,000 years before European colonization. The name of the preserve is derived from their language. It refers to one past use of the area — a place to weave baskets. Today, the Ohlone don’t have a reservation, a great injustice, although there are private efforts to repatriate land and provide a basis for the small number of remaining Ohlone to revive their culture.

While on top of a levee, I got a sense of how beautiful the valley must have been under Ohlone care. With a little research, I learned it was a paradise made even more bountiful by the Ohlone’s land management practices. An unrestrained river fed fertile bottom land. Herds of tule elk, pronghorn, and mule deer roamed the grasslands and forests. Streams teemed with salmon, perch, and stickleback. Waterfowl were plentiful and a key Ohlone food source. As is the case today, man and beast enjoyed one of the most hospitable climates on the continent. The first European to set eyes on Santa Clara Valley, Jose Ortega, called it, “Llano de los Robles,” the valley of the oaks.

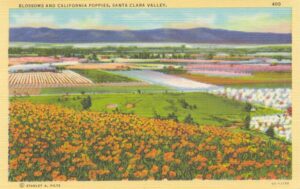

Much later, after the Ohlone were decimated by European settlers, it was called The Valley of Heart’s Delight due to the abundance of orchards, flowering trees, and plants. I’ve seen old postcards of the valley. The adjective idyllic would not be an exaggeration. It was a paradise too, though of a vastly different kind.

Underneath all the subdivisions, office parks, and asphalt is some of the best soil in California. As a longtime gardener here, I can attest to the fertility of the soil. You can grow almost anything here.

Now the area is famously known as Silicon Valley. It’s a real life example of a place where, as Joni Mitchell sang, “they paved paradise and put up a parking lot.”

While Silicon Valley is celebrated globally as a regional economic powerhouse, it looks much different from a historical perspective. To me it looks like paradise destroyed twice. My appreciation for the beauty that remains is intensely bittersweet. The area’s incredible economic success seems a grossly insufficient consolation prize. The march of time can’t be stopped, but surely much more of what once was could have been carried forward to enrich us all. Instead, our shared heritage — both indigenous and colonial — has been almost completely wiped out. Tiny, broken fragments remain like this precious preserve. All for what? So few got rich in treasure, while we’re all left poorer in soul.

On this Thanksgiving weekend, I’m keeping this complicated history in mind, meditating on what has been lost, and giving thanks for the beauty that has been saved. We can’t rewrite history, but we can write a future with more soul, wisdom, and reverence for our shared heritage.