America is becoming increasingly and dangerously waterlogged. And it’s not just rural areas. Cities are especially vulnerable to a phenomenon called urban flooding because they are less permeable than their rural counterparts due to concrete surfaces and inadequate infrastructure. Runoff overflow can turn streets into rivers. According to the Natural Resources Defense Council, by the end of the century, floodplains could increase by as much as 45 percent, with climate change causing heavier rains and more storms. Fixing deteriorated pipes and building more infrastructure will help cities, but it’s expensive and disruptive. Fortunately, cities have another solution that’s cheaper, more sustainable, and can lift up communities and provide jobs: a back-to-nature approach called “green infrastructure.”

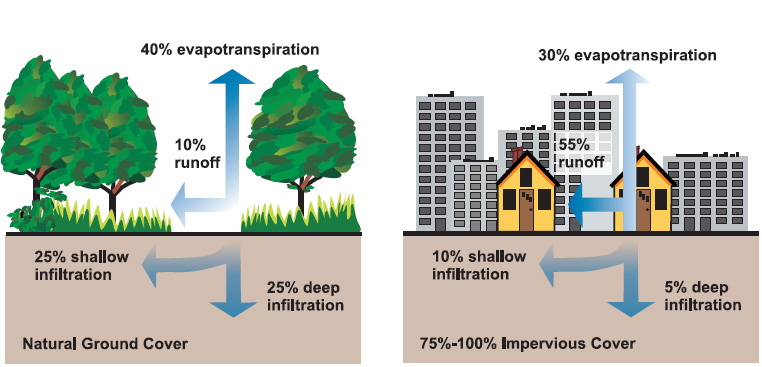

Green infrastructure is, at its core, about utilizing nature to manage storm-water. Pavement is impermeable, but vegetation and soil have an innate ability to manage water before it ever reaches a city’s sewers. Through strategically planted trees, parks, and wetlands, cities can reduce strain on their sewer systems, and reduce pollution at the same time. The Democracy Collaborative recently released a report recommending the use of green infrastructure as a community-based climate adaptation strategy.

Johanna Bozuwa, who authored the report, said in an interview: “We’re seeing the power of nature, every day. Some of our man-made solutions can’t stand up to what is happening around us… nature knows how to deal with these things better than we do, and it’s been around so much longer. The biomimicry community has found that we can use what is already here for our benefit and it will have positive ramifications.”

Green infrastructure is an appealing policy solution because it has benefits far beyond storm-water management — research has long shown that increasing vegetation and green space increases quality of life in a community. “The exciting thing about green infrastructure is obviously this storm-water management piece,” said Bozuwa. “But if we are literally ripping up concrete and putting in trees, or shrubs, or even parks, that is going to have a multiplicity of benefits.”

Besides the positive impact on people’s health, green infrastructure also has the capacity to lift up communities economically through well-paying, quality local jobs. “So much of the infrastructure [for water] has been disinvested in the United States and as there’s a mounting issue of climate change, storm-water infrastructure is becoming more and more apparent as a necessary intervention in order for us to have climate resilient cities,” said Bozuwa. “We zeroed in on green infrastructure because we saw some of this potential for job creation and providing jobs to underserved and marginalized communities.”

Because green infrastructure is a distributed solution that requires longer-term maintenance but lower upfront costs, it is ideal for worker cooperatives (democratically owned and operated businesses) and social enterprises (nonprofits that have a fee-for-service component) in low-income communities where jobs are needed. Green infrastructure workers can be trained on the job and the work can offer upward mobility while increasing climate resilience. However, to work as a community resiliency model, Bozuwa emphasized that green infrastructure initiatives will have to be carefully designed to avoid displacement and gentrification: working deeply with the community, coordinating with existing unions, and led by residents.

In her report, Bozuwa mentions several case studies of effective green infrastructure initiatives, one of which is the nonprofit group Verde’s landscaping project in the majority-Latinx Cully neighborhood of Portland, Oregon. Verde Landscape is a social enterprise landscaping firm with a four-year training program that can lead to long-term employment or prepare participants to start their own businesses. One of the things that struck Bozuwa about the Verde project is that it was started by an existing community group that works on affordable housing, Hacienda CDC, which is based in the neighborhood.

“One really interesting piece [in my fieldwork] was the persistence with which this activists and community organizers are thinking about the displacement potential of green infrastructure if we don’t design our housing and think of these things as systems,” said Bozuwa. “And that is a reason why the Verde model is so compelling.”

Bozuwa and the Democracy Collaborative were attracted to green infrastructure as a route to long-term, community-led climate resilience. She is hopeful that green infrastructure will continue to be put in place in cities around the United States. Green infrastructure projects are already around the country in cities like Seattle, Washington DC, Oakland, California, Buffalo, New York, and others.

Some U.S. cities are already under consent decrees, agreements with the Environmental Protection Agency to reduce storm-water runoff and sewer overflow. Green infrastructure could be part of that commitment. Green infrastructure can work very effectively alongside traditional gray infrastructure, such as structures made of concrete, and act as a community development tool at the same time. Climate resiliency will require both large-scale infrastructure projects and smaller ones, but greening America’s cities from the ground up is a climate solution worth getting behind.

##

This article is part of our series on disaster collectivism. Download our free series ebook here.