The Academy of Sciences in San Francisco—a marvel of sustainable architecture and engineering—contains a participatory exhibit called “What’s your carbon footprint?” which is part of a larger installation on climate change in California. Its design is ingenious: Six sliders measure factors like home energy use, air travel, public transportation and carpooling, and so on.

As you estimate how many airplane flights you take each year, how many miles you bike, and so on, you move weights up and down the sliders—and these combine to weigh how much carbon you produce, from major emitter to light footprint.

As you estimate how many airplane flights you take each year, how many miles you bike, and so on, you move weights up and down the sliders—and these combine to weigh how much carbon you produce, from major emitter to light footprint.

I spent an hour watching people from all over the United States measure their carbon footprints, and the results were quite depressing. Nearly every person came down solidly as a “major emitter”—or, as the scale accusingly puts it, as an average “unmindful American."

Families of three or more sat especially heavy on the earth. Predictably, most of these families drove everywhere, rode very little public transport, and did not walk or bike on a daily basis.

“We suck,” said one woman to her boyfriend, her shoulders slumping—but she could have been speaking for everybody that afternoon.

“We suck,” said one woman to her boyfriend, her shoulders slumping—but she could have been speaking for everybody that afternoon.

My own footprint is vanishingly small—it's the same as the average Brazilian or average Chinese, according to the scale. The reason for this is simple: We don’t own a car. Plus, we’re a family of three living in a two-bedroom apartment in the city—we actually share our Victorian with three other people, six in one house.

So I get to feel pretty smug, don’t I? But I don’t think it’s intrinsic virtue that makes my family into “conscientious Americans,” as the scale would have it. This arises from our circumstances in the city, and the fact that we don’t have a lot of disposable income—what surplus we have we generally plow into my son’s education.

I interviewed several of the families with heavy carbon footprints, mainly to find out if the scale would cause them to go home and rethink their lifestyles. One dad from San Ramon, California, said yes, but it was tough: He had to travel by plane at least six times a year for work, and air travel is a carbon-breathing monster, as we learned. His children’s school was a ten-minute walk away, which helps, but he felt that their city was arranged so that they needed a car to get anywhere.

His answer was fairly typical: Most people felt they were doing what they could, but they had trouble envisioning any other kind of life. They’d consider small changes, sure—many told me that they were already trying to drive less, if only to save money—but truly shrinking their carbon footprint would demand such a revolutionary overhaul of their (largely suburban or exurban) lives, they couldn’t imagine it.

“I think the government and corporations need to do more,” said one mother of two, expressing a sentiment common among the more thoughtful museum-goers I interviewed. “I’m just one person. I’d like to see more bike lanes and I’d like to see towns like ours designed differently, so that we could walk more. I think we need incentives to do things like take the train, and the trains have to be clean and reliable. And I think business could do a lot more. A lot of air travel isn’t necessary; we can teleconference.”

It might sound as though people like this mom are avoiding personal responsibility, but I think they are just seeing the situation accurately: As Green Metropolis author David Owen suggests in his Shareable Q&A, sustainability is a context, not an individual act of virtue. If that context is urban, then we have to ask ourselves: What can we do to make cities more attractive, especially to carbon-producing families?

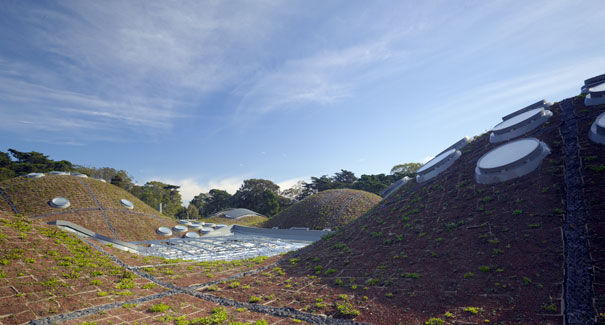

It's not a matter of aesthetics; cities have suburbs beat on that front. Architects like Tzannes Associates in Sydney, Australia, have proposed bottling the suburbs in a skyscraper, with modular gardens, parks, sporting fields, community centers, and homes stacked on top of each other (the green pillar above). This might help attract some affluent families to the city, but a proposal like this does nothing to respond to the main reasons why families flee, namely quality of schools and cost of living. Developments like these also need to be coupled with accessible, pleasant public transportation, as I'm sure the architects would readily agree.

From this perspective, the best thing any of us can do to save the earth is to raise money, march, and vote for ballot initiatives and politicians that encourage urban density, education, public transportation, and social equality–not things we think of as being environmental issues. The first step in that process—the way to create a sense of urgency—is through exhibits like “What is your carbon footprint?” I could see the impact in people’s eyes, as the scale hit bottom with a clunk. They could see themselves as part of the problem. The trick is to help people to see themselves as part of the solution, as well.