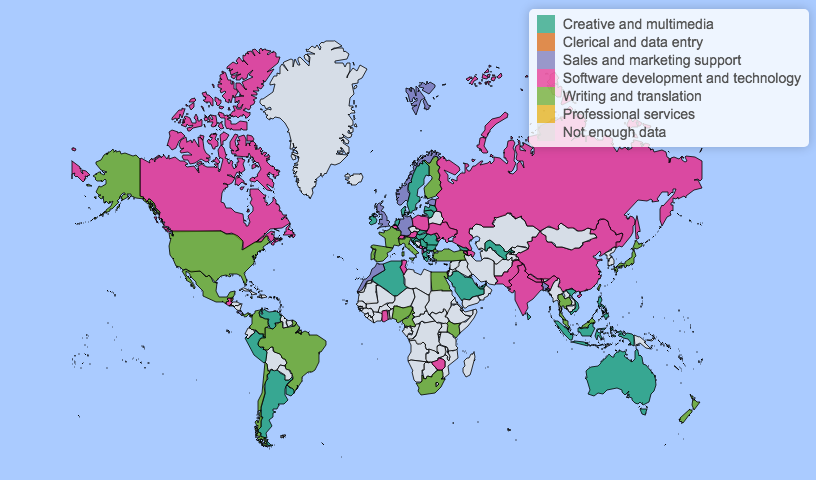

This month, researchers at the Oxford Internet Institute, part of the University of Oxford, England, released their first worker supplement to the Online Labour index, which measures the gig economy in real time. The supplement — complete with an interactive map — details the contribution of a number of countries to the global freelance marketplace. It's a fascinating snapshot of where freelancers are working across the world, and it is especially interesting to note the burgeoning freelance market in developing nations. Here's an excerpt from the report with a few of its key takeaways:

"The largest overall supplier of online labour according to the data is the traditional outsourcing destination India, which is home to 24 percent of the workers observed. India is followed by Bangladesh (16%) and United States (12%). Different countries' workers focus on different occupations. The software development and technology category is dominated by workers from the Indian subcontinent, who command a 55 percent market share. The professional services category, which consists of services such as accounting, legal services, and business consulting, is led by UK-based workers with a 22 percent market share."

The Online Index, which launched in 2016, tracks trends in the gig economy and measures changes in the use of online labor platforms globally. It's spearheaded by Otto Kässi and Vili Lehdonyirta, both researchers at the Oxford Internet Institute. They bill the Index as the first indicator for the online gig economy equal to that of more conventional workforce indicators, like ones produced by the Bureau of Labor Statistics in the U.S. The research group found that in 2016, the online gig economy grew by an incredible 26 percent.

"Before we published our data, the previous attempts of measuring the market have either concentrated on a single platform or on individual snapshots of the data," Kässi said. "We, on the other hand, use a consistent methodology across all of the platforms we track. Further, we publish our aggregated data as an open data set, so anyone can download it and do their own analyses."

The supplement expands that project even further. "We thought that even the very basic questions of the online freelancing market were not properly addressed," Kässi said. "Where are the workers? What kind of work is offered and where?" These questions are essential in not only understanding the scope of the freelance market, but also in designing policies and programs that protect workers. The report and interactive map derive data from large online platforms for freelance workers and employers, including Fiverr, Freelancer, Guru, and PeoplePerHour. Researchers also developed a tool that allows anyone to search the data sets and create visualizations of their own findings. Andrew Karpie, a research director for the advisory firm, Spend Matters, performed his own analysis, which he published in a blog post.

Karpie found that the work exchange is largely happening between the U.S. and some developing countries in Asia. He wrote that "from our perspective, this is likely true for three main reasons: (1) wage arbitrage (frequently), (2) lower transaction costs and (3) supply of skilled labor/talent (with shortages in the U.S.)."

Here's his list of key takeaways:

-

Roughly 60% of online workers are located in Asia (namely India, Pakistan, Bangladesh and the Philippines).

-

The largest occupational categories of online workers are software/IT (30%+), creative and media (25%+), and sales and marketing (under 20%). Writing and translation is also important, at about 13%

-

Harkening back to the demand-side data of our prior article, on the demand side, the U.S. and Canada account for over 50% of the global total projects requested. About 65% of all projects requested in the U.S. and Canada are software/IT and creative and multimedia projects (about 40% and 25%, respectively).

While Karpie is working on the business side, Kässi said that these new data points are already being used by academics to guide their own qualitative data collection. Because the map is frequently updated with fresh details, researchers may now be able to track changes in the digital marketplace, and he said it will be interesting to see the stability of each country's freelance pool.

For example, he points to a digital job training program in Kenya called the Ajira Digital Program. If the program takes off, "this should be visible in our data as well," he said. The program, which is sponsored by the Kenyan government, used index data to develop targeted training. Theoretically, the map could show how "large economic shocks to individual countries might percolate into online freelancing labour markets as extra labour supply from those countries."

That's speculation for now, he says. Past research suggests that the entry point to the online market can be difficult for fledgling freelancers. Since the supply of workers far outpaces the demand for the work, there might be "inertia" in the index, according to Kässi. Also, the index only tracks the largest online markets, which are in English so the distribution across non-English language markets might be different.

Kässi was surprised by the contribution of highly developed countries —10 percent of online workers are in the U.S. and seven percent in the U.K. "This means that there is a population for whom digital freelancing is legitimate source of at least some income even in some rich western countries."

Header image is a screenshot of the Online Labour Index's interactive map.