On August 29, 2023, Georgia Attorney General Chris Carr filed an indictment against 61 members of the movement to Defend the Atlanta Forest and Stop Cop City. The indictment alleges a vast criminal conspiracy on the part of the activists, weaving them together in a legal scheme so fantastical that one of the accused is cited for being reimbursed for Elmer’s Glue.

It’s a patchwork case with Carr — the announced 2026 Georgia gubernatorial candidate — creating a veritable Charlotte’s Web; scrawling words in the web in a desperate ploy for attention. Unfortunately, it also represents a brazen assault on social justice organizers reminiscent of the FBI’s surveillance and attacks on the Civil Rights and Black Power movements in the 1960s and 70s.

In order to justify the harsh charges, each carrying up to 25 years in prison, Carr attempts to link the protestors together based on their shared commitments to collective welfare and mutual aid. In other words, the State of Georgia is currently arguing that participation in mutual aid projects and practicing solidarity constitutes furthering a criminal conspiracy.

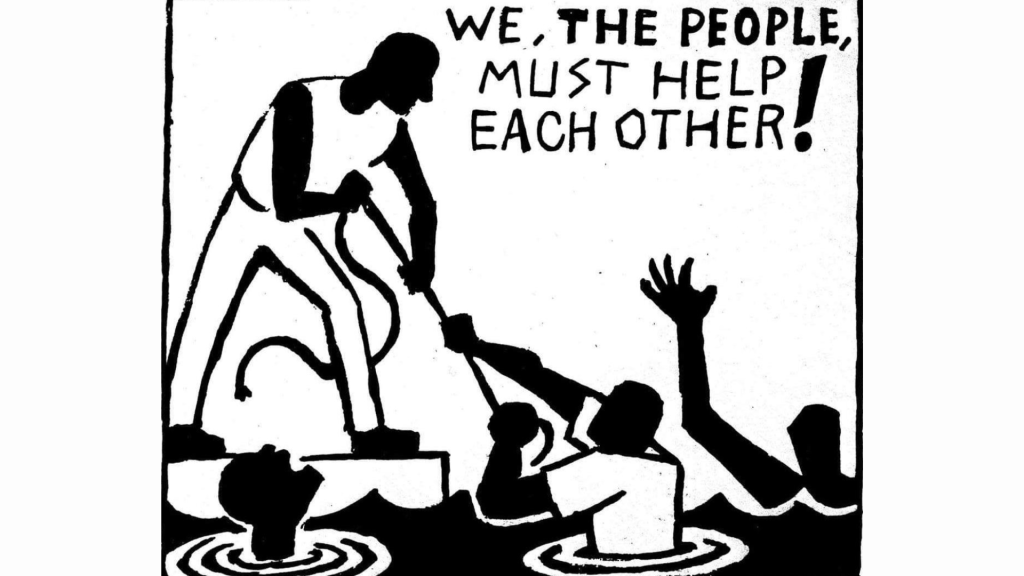

If Carr is going to try to make a twisted image of mutual aid tantamount to terrorism, we should all get clear on what mutual aid really is.

What is mutual aid?

Mutual aid is a term used for the part of social movement work where people provide for each other’s direct needs like food, health care, housing, or transportation. Social movement struggles are often motivated by frustration that people can’t get the basic things they need to live because corporations, bosses, and governments have organized life to make them exploitable. Movements respond by providing directly to people in crisis while fighting to change the systems that are causing those conditions. For example, workers will support each other while on strike so that they can eat and pay rent, while mobilizing to change the conditions.

In the movement to Stop Cop City, three organizers with the Atlanta Solidarity Fund find themselves in the middle of this legal storm. Adele MacLean, 42, Marlon Scott Kautz, 39, and Savannah Patterson, 30, were arrested over the summer on charges of charity fraud and money laundering. Now, Chris Carr has added RICO charges to that list.

But these organizers aren’t frauds out to steal money from unsuspecting donors to spend it on terrorists, as Carr’s indictment suggests. They are people engaged in social movement work to support people in crisis and stop harmful government action. In addition to working with the Atlanta Solidarity Fund to bail people out of jail, MacLean, Kautz and Patterson also operate a mutual aid effort called Food 4 Life ATL, which has distributed tens of thousands of meals in just a few short years, similar to other food justice mutual aid projects all over the country. According to the State of Georgia, those meals were evidence of a crime.

Atlanta has a vibrant network of mutual aid projects providing things people need to get by, and mobilizing people to fight back together. EndstateAtl, a Black queer feminist effort to “build the future we imagine,” helps people pay their power bills, provides food, creates events to connect people, and has a library.

Metro Atlanta Mutual Aid Fund helps people who are out of work — due to COVID-19 and other crises — pay their bills. Community Movement Builders’ mutual aid program helps Black residents living in southeast and southwest Atlanta to buy food, water and other basic supplies. Kamau Franklin, founder of Community Movement Builders, describes the practice as central to the group’s organizing philosophy.

“We believe mutual aid is a core element in demonstrating alternative ways to be in community with each other,” says Franklin. “It is a way that is reliant on the participation and politicalization of those who are in the community. We pack together, distribute food and toiletries together, and engage in political education together. This is how we create communities that have power and challenge those who have power over us.”

And these are only a few of many. Chances are, no matter where you’re living, there are mutual aid projects on the ground meeting the needs of everyday people and helping mobilize people to fight for change together in their communities.

Mutual aid in U.S. history

There is nothing new about mutual aid — it has been part of organized resistance for the entire history of this country, and before this country existed. As Ariel Aberg-Riger illustrates beautifully, Black people escaping slavery were supported by large mutual aid projects in the northern cities that received them, and helped them find housing and basic necessities.

Similarly, migrant communities in the late 1800s to early 1900s established mutual aid networks to receive people arriving at ports with nothing but the clothes on their backs, not speaking the language, and needing community help to survive in a new place. The Underground Railroad itself can be understood to be a big mutual aid project: it was part of the resistance to the slavery system overall, and it was direct support to individual enslaved people to get them out of that system.

Or, consider the Montgomery Bus Boycott. To implement the boycott, working class Black people, especially women, and their allies coordinated transportation for tens of thousands of Black workers in Montgomery for over a year — organizing rides, raising money to buy cars, creating schedules for pick-ups and drop-offs — a giant mutual aid project that gave them the leverage to fight the segregated bus system.

The Black Panther Party’s free breakfast program is perhaps one of the most famous examples of a 20th century social movement providing direct support with basic needs to a community as part of building power to fight back. The breakfast program was a place for people to get something they needed and connect about why Black people were so impoverished in the U.S. and build a shared sense of empowerment about how Black people could take care of each other.

Today, mutual aid projects are very visible in communities facing all kinds of criminalization and imprisonment. Prison-letter-writing projects exist all over the U.S. to support people who are isolated inside prisons, facing the nutritional deprivation, health care denial, and violence that is ubiquitous in the massive U.S. prison system (the largest in the world).

Similar projects exist focused on people in U.S. immigration detention prisons. Mutual aid is also visible at the U.S. border, where groups like No More Deaths have been putting water in the desert to try to prevent the deaths of those making dangerous crossings, and providing medical aid to migrants.

Which is all to say: Mutual aid is something that people in all kinds of social movements do and have done.

Carr’s indictment focuses on mutual aid and solidarity being something anarchists do, and hopes to justify criminalization by scaring people with the word “anarchist.” It’s true, some activists involved in the Stop Cop City campaign are anarchists — meaning that they want to abolish borders, police, and militaries — and some are not anarchists, but everyone involved in Stop Cop City, and in defending the forest, are like the people in movements described above. They are opposed to police violence and racism, and are fighting for a world in which people have what they need to live, and trying hard to give each other what is needed to survive right now.

People from many different movements and political philosophies do mutual aid projects to help each other out, and to recruit people to fight for change together. Within strategies like those used in Atlanta – where people actively occupied a forest while dealing with police harassment, bringing together community for conversations, providing food and rain protection, getting a generator, and other basic things that were mentioned in the indictment — are practical, standard parts of organizing.

We join social movements because we care about unfair and harmful things that are happening to ourselves and others, so it makes sense that social movements address those conditions directly with material support to people for basic needs. Movement combines directly attending to those conditions with working to try to change the system itself, such as by stopping the expansion of police infrastructure.

How to make helping people a crime

There is nothing new about police and prosecutors targeting mutual aid efforts for criminalization, unfortunately. The Black Panther Party’s free breakfast program is a good example. The Panthers’ mutual aid projects, which they called Survival Programs, such as free clinics, an ambulance service, schools, and elder accompaniment programs, were very popular. Law enforcement saw these programs as a threat because they helped people see what the Panthers were opposing (impoverishment and abuse of Black populations) and legitimized the Panther’s resistance.

J. Edgar Hoover, head of the FBI at the time, while describing the Party as “the greatest threat to internal security of the country,” famously focused on the free breakfast program. In many cities where the Panthers provided breakfast, cops raided and destroyed their food rather than see it go to those in need. Attacking the Panthers’ mutual aid projects went hand-in-hand with law enforcement infiltration of the organization, arrests and assassinations of the members.

Other examples of the criminalization of mutual aid include the Trump administration’s raids on the No More Death’s humanitarian aid stations at the U.S./Mexico border, as well as the more recent arrests of people trying to offer free food in places like Houston, Texas and Bullhead City, Arizona.

In fact, there is a long history of people being criminalized for offering free food to unhoused people, and— in the period since 2020 when mutual aid projects expanded to support rising numbers of unhoused people — more cities are passing ordinances to criminalize providing this form of mutual aid. Even before the sharp rise in mutual aid projects and city efforts to criminalize them, arresting people for giving out food to the poor was common in U.S. cities. In November 2019, members of the Atlanta chapter of Food Not Bombs faced police harassment and arrest for giving out food outside an apartment complex in Decatur.

Why do police — from local law enforcement to the FBI — care so much about people giving out free food and other necessities? Why would J. Edgar Hoover or Chris Carr suggest that such basic community care is a threat to social order and the nation, and is somehow connected to terrorism? It’s because mutual aid is, in fact, incredibly important to liberation struggles.

Law enforcement agencies seeking to repress social movements recognize that mutual aid is a vital part of resistance struggles that seek to change conditions, including movements that oppose the racist policing and punishment system. If they recognize it, then we should too.

An on-ramp to movement

Mutual aid is one of the main ways that people join movements. Sometimes they show up needing something, and people in the movement offer it to them and invite them to join the fight to change these conditions for everyone. They may simply find out about what’s happening and want to help those suffering and fight for change. Most people active in social movements are doing mutual aid work of one kind or another. So it makes sense that if police and prosecutors want to suppress movements, they will try to make mutual aid a crime.

In the case of the Stop Cop City indictment, Carr is fabricating an outrageous narrative that people engaged in a campaign to stop an unpopular police expansion project are actually a criminal conspiracy, and, therefore, every time they buy food, put up a tent or make a flier, it is a crime.

Anyone who cares about people being able to oppose bad government action should be concerned about this, but it goes beyond that. In the age of climate collapse, as more and more people are in crisis and lack basic necessities — and as the government continues to be utterly inadequate at supporting the growing numbers of poor, unhoused, and displaced people — anyone who cares about our ability to step up ministration for each other should be worried about this indictment.

This indictment criminalizes both our ability to oppose projects that destroy the environment and expand policing, and our ability to support each other’s survival.