Extreme heat is already the deadliest climate and weather-related hazard in the United States and cities are getting hotter because of climate change and the urban heat island effect. Communities everywhere need to proactively address inequitable heat risks, but compared with other more visible hazards like flooding, heat governance is underdeveloped. In the first Cities@Tufts lecture of 2022, Sara Meerow synthesizes the current state of extreme heat governance research and practice and outlines a framework for urban heat resilience.

We have included the transcript, graphic recording, audio, and video from “Urban heat resilience: Governing an invisible hazard” presented by Sara Meerow on February 9, 2022.

About the presenter

Dr. Sara Meerow is an assistant professor in the School of Geographical Sciences and Urban Planning at Arizona State University. She is an interdisciplinary scholar working at the intersection of urban geography and planning to tackle the challenge of making cities more resilient in the face of climate change and other social and environmental hazards, while at the same time more sustainable and just. Her research, which has been published in a wide range of academic journals, includes more conceptual studies of urban resilience as well as empirical research on city governance of resilience, green infrastructure, and climate change adaptation in a range of cities. Sara leads the Planning for Urban Resilience Lab at ASU and some of her research group’s current projects focus on planning for extreme heat, flooding, and multifunctional green infrastructure. She holds a PhD from the School of Natural Resources and Environment (now the School for Environment and Sustainability) at the University of Michigan and an MS in international development studies from the University of Amsterdam.

Shareable is partnering with Tufts University on this special series hosted by professor Julian Agyeman (Co-chair of Shareable’s Board) and Cities@Tufts. Initially designed for Tufts students, faculty, and alumni, the colloquium has been opened up to the public with the support of Shareable, and The Kresge Foundation.

Cities@Tufts Lectures explores the impact of urban planning on our communities and the opportunities to design for greater equity and justice.

Register to participate in future Cities@Tufts events here.

Listen to the Cities@Tufts Podcast (or on the app of your choice):

“Urban heat resilience: Governing an invisible hazard” Transcript

Sara Meerow: [00:00:06] Heat justice needs to be central to planning for urban heat, and that means not just making sure that heat risks and strategies are going to be fairly distributed, but also recognizing that they haven’t been historically — and then customizing strategies to actually really meet the different needs that these communities have.

Tom Llewellyn: [00:00:26] Can a cooperative cities framework address the unequal impact of automated traffic fines in Black and Brown communities? How can alternative land governance models help us respond to our climate challenge? Is there an equity measurement scheme that can bring clean energy programs and investments to frontline communities? These are just a few of the questions we’ll be exploring this season on Cities@Tufts Lectures, a free, live event and podcast series where we explore the impact of urban planning on our communities and the opportunities to design for greater equity and justice.

[00:00:56] I’m your host, Tom Llewellyn. Welcome back for season three. We’re glad to have you with us. Today on the show. we’re featuring Sara Meerow’s lecture, “Urban Heat Resilience: Governing an Invisible Hazard.” In addition to this audio version, you can watch the video, check out the graphic recording and read the full transcript on Sharable.net. While you’re there, take some time to get caught up on all of our past lectures, and now here’s Professor Julian Agyeman who will welcome you to the Cities@Tufts Spring Colloquium and introduce today’s lecturer.

Julian Agyeman: [00:01:36] Welcome to the Cities@Tufts colloquium, along with our partners, Shareable, the Kresge Foundation and the Barr Foundation. I’m Professor Julian Agyeman and together with my research associates Perri Sheinbaum and Caitlin McLennan, we organized Cities@Tufts as a cross-disciplinary academic initiative which recognizes Tufts University as a leader in urban studies, urban planning and sustainability issues. We’d like to acknowledge that Tufts University’s Medford campus is located on colonized Wampanoag and Massachusetts territory.

[00:02:10] Today, we are beyond delighted to welcome our first speaker of 2020 to and that is Sara Meerow. Sara is an assistant professor in the School of Geographical Sciences and Urban Planning at Arizona State University. She’s an interdisciplinary scholar working at the intersection of urban geography and planning, and she’s looking at tackling the challenges of making cities more resilient in the face of climate change and other social and environmental hazards.

[00:02:40] She also is, I think, looking at issues of justice and sustainability, justice, sustainability, strangely enough. And Sarah’s current projects focus on planning for extreme heat flooding and multi-functional green infrastructure. And I was saying to Sara before that several of my thesis advisors who are looking at green infrastructure are actually using Sarah’s work. So as an academic, you’re work often does get cited. She’s got a Ph.D. from the School of Natural Resources and Environment, now the School of Environment and Sustainability at University of Michigan, and she has an MS in International Development Studies from the University of Amsterdam. Her talk today is “Urban Heat Resilience: Governing an Invisible Hazard.” Sara, a Zoom-tastic welcome to the Cities@Tufts Colloquium. Thank you, Sara.

Sara Meerow: [00:03:29] Great. Thank you so much for the introduction. I don’t really need to do anymore in terms of introducing myself. I really appreciate that. And obviously your work on just sustainability, Julian, has been long an inspiration to me, going back to my PhD, so it’s really an honor to be here. And while my work is more broadly focused on planning for urban resilience, today I’m really going to focus on one particular hazard that I’ve been thinking a lot about lately, which is extreme heat. And no matter where you’re at, you probably notice that it’s getting hotter, right? So 2010 to 2019 was the hottest decade on record, 2020 was the hottest year, and we’ve seen numerous record breaking heat waves in recent years, many of which have had really unfortunate and deadly consequences. And I think people are starting to take notice.

[00:04:20] And so why is it getting hotter, right? I probably don’t need to tell all of you that temperatures are increasing globally due to climate change. So the Earth has already warmed over one degree Celsius, almost two degrees Fahrenheit. That might not sound like a lot, but even a small shift in global average temperatures can mean a big increase in the number of extreme heat days. And in fact, the latest IPCC report that just came out, the 6th Assessment Report, includes this graphic that you can see here that just one point five degrees of warming right, which is basically our current target, a heat event that would have previously occurred once in 50 years is now expected to occur eight times in the same period. So we’re looking at a lot more really hot days everywhere.

[00:05:08] And urban areas are actually warming at an even faster rate than surrounding areas because of something called the urban heat island effect, which is a phenomenon where urbanized areas are hotter than their surrounding or natural areas because of the built environment and waste heat. And this combination of climate change and the urban heat island effect means that cities are dealing with much more extreme heat than they used to. So just for example, I’m here essentially in the city of Phoenix, right? And from 1970-2018 temperatures in the city increased an average of 2.4 degrees Celsius — over 4 degrees Fahrenheit — which is more than twice the average for the whole contiguous U.S. So that warming trend, I think, really becomes clear if you look at something like Phoenix’s climate stripes. So you just see that recent years, it’s a lot hotter than it used to be.

[00:06:05] It’s also clear that heat exposure and these increases are not evenly distributed across cities. So there have been several recent studies, including one by Vivek Shandas, who I know was a previous speaker in this series, just last semester, have shown that neighborhoods that were formerly red-lined or often were higher percentage minority neighborhoods are hotter today due primarily to differences in characteristics of the built environment and vegetation that are due to those legacy effects and of racism and underinvestment in these areas.

[00:06:38] So why should all of this worry, right? Well, I think for a starter, the most obvious is that heat kills. It’s already the deadliest weather related disaster, killing thousands of people each year. And just for example, where I am in Maricopa County, Arizona, they do quite a lot of analysis of heat-related deaths, and it’s very clear that they’ve been on the rise. So in 2020, there were more than three hundred heat related deaths, which really shattered previous records. And in addition to heat related deaths and even a larger share of illnesses, there are other impacts that heat causes to quality of life, the economy, water and energy use, and even communities that traditionally haven’t worried a lot about heat — they’re having to do that now. I mean, just look at what happened last summer in the Pacific Northwest, which had previously not been an area that people really thought of as a concern for extreme heat, right? And now they had this extremely deadly heat wave.

[00:07:42] Also, we know that all of these heat impacts aren’t evenly distributed across the population — they’re not equitable. Just to give an illustration, if we dig back into the Maricopa County heat deaths in 202, we can see the black and American Indian residents perished at much higher rates than the rest of the population. So 15 percent of those who died were African-American while they actually only account for six percent of the population in Maricopa County and four percent of those who died were American Indian, while they’re just two percent of the population. We also can see that actually more than half of those who died were experiencing homelessness. So clearly, heat is also an equity issue.

[00:08:25] So hopefully, this gives you just a very brief introduction to the extreme heat challenge. Now I’m going to shift gears a little bit and talk about some of the work that I’ve been doing on how we actually tackle this problem with heat governance. So to start off, my colleague at the University of Arizona, Ladd Keith, who I’ve been doing a lot of this heat work with, we set out to try and figure out how urban planners in communities across the U.S. are thinking about extreme heat. So what we did was we conducted a survey on two different samples to really get as wide as possible a range of perspectives. So the one that I will reference throughout the rest of this talk was a stratified random sample of urban planners from 69 cities of different sizes and different climate regions. So again, we really wanted to get cities of different sizes, as well as across different climate regions, heat risk levels to really understand what is the current state of practice on heat. We also had a convenient sample of another nearly one hundred planning professionals from across the US, which you can see the gray map where they were located.

[00:09:31] So when it comes to heat impacts, one of the big takeaways from our survey was that more than 80 percent of the planners who responded said that their communities were impacted in some way by heat. The top five most commonly reported impacts were to energy and water use, urban vegetation, public health and quality of life. On the other side, retail and economic development were not as commonly reported impacts. So given the high rate of reported impacts, it’s not that surprising that the majority of planners indicated that they were somewhat to very concerned about extreme heat impacts overall, as well as to economic, environmental and health impacts specifically. So planners were most concerned actually about impacts to the environment and public health, a little bit less so those economic impacts, which relates to what they also reported, right? And planners, interestingly, were more concerned about climate change as a contributor to urban heat than they were to the urban heat island — despite traditionally arguably planners having more influence over the urban heat island, right?

[00:10:41] Oh, and I see there’s a question about the response rate to the survey, so we sent it out. I believe it was to 111 cities and received 69 responses, so it was an over 60 percent response rate. So we were pretty happy with that and had a good representation across the regions and the different city-size groups as well.

[00:10:59] So in addition to the survey, Ladd and I also dug into the academic literature on heat planning to really try and assess this current state of research, as well — so we look at practice, we also looked at research on heat planning. And what our systematic literature reviews suggested is that really the vast majority of studies have focused on heat modeling. So modeling urban heat islands, modeling or mapping vulnerability, along with some focus on the relationship between specific design elements and features and characteristics and cities and heat. But there’s really not been a lot of work that’s focused on how we actually manage this hazard, right? So just seven percent of the heat planning studies in our sample dug into planning or governance processes — actually focused on how we deal with heat, right? And the few papers that did that really mostly concluded that current efforts to deal with extreme heat are very fragmented, that it’s often a really invisible problem that’s not necessarily prioritized and no one’s really responsible or accountable for dealing with it.

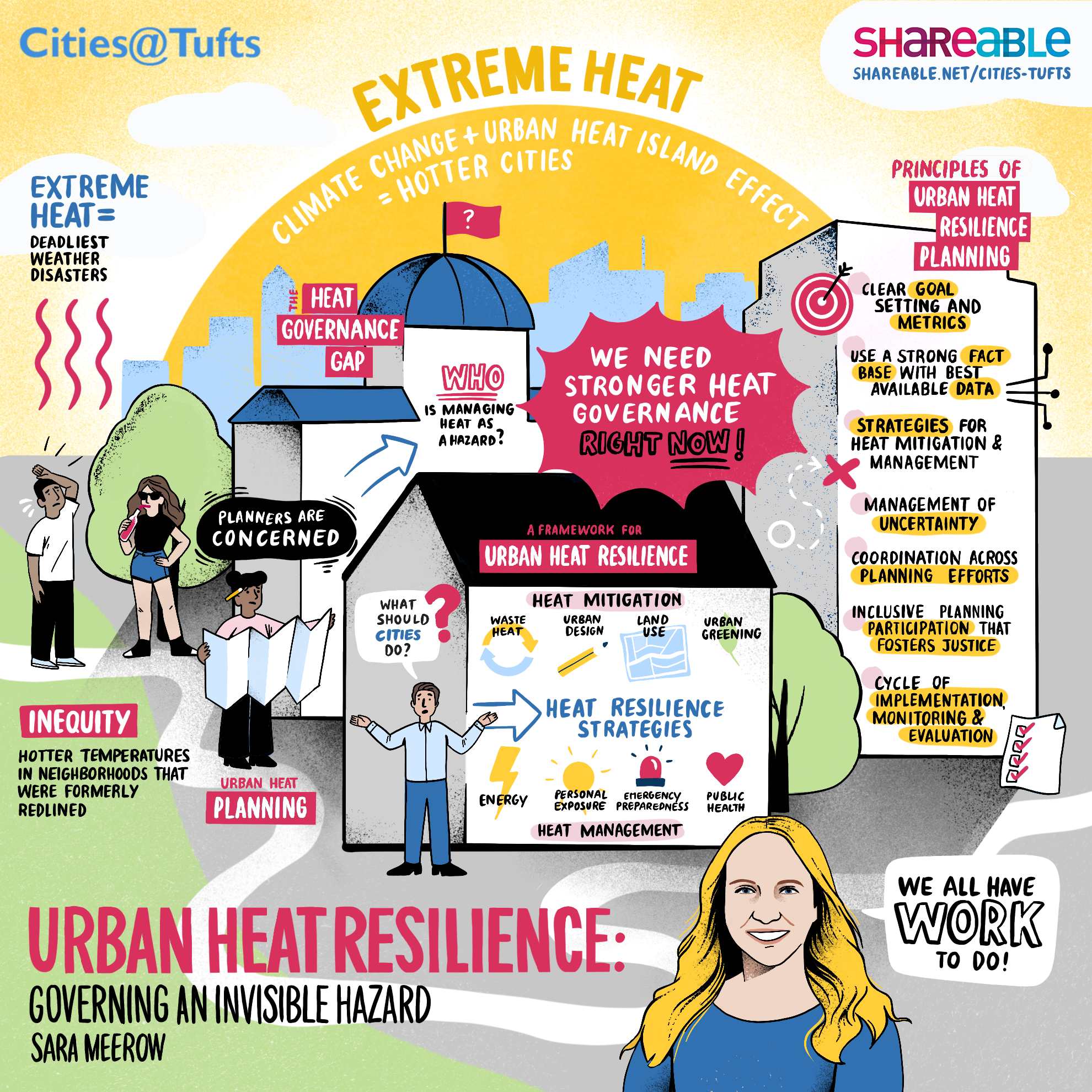

[00:12:11] So I would argue, as we did in a recent comment in Nature, that we need stronger heat governance right now. And when I say heat governance, what I mean are the actors, strategies, and processes, as well as institutions that actually guide decision making for both mitigating heat and cities — so reducing heat — and managing the impacts. So in our comment, we outlined six guiding principles for what we thought was needed for better heat governance. So first, we said that equity needs to be front and center because we know that these risks are highly uneven, as I’ve already talked about. Second, we need to invest in both mitigation and management strategies, and these need to be connected. We need more consistent metrics for both of these goals. We need to coordinate all of these initiatives again so that mitigation and management aren’t siloed and as well that we integrate our plans, and we need stronger heat institutions at the local level. This might mean, for example, having heat officers or a dedicated heat office as several cities have tried to do now. Or at the national level, a clear agency that is really responsible for coordinating heat policy, which at the moment is somewhat lacking.

[00:13:25] So that’s really kind of sketching out a big picture of what’s needed for heat governance. But for a particular city that wants to proactively plan for extreme heat, what should they do? Where should they start, right? So Ladd Keith and I are actually currently finalizing what will be an open access — so publicly available report for the American Planning Association on Urban Heat Resilience. And in it, we lay out a framework for heat resilience. And so I’m going to spend the rest of my time today walking you through some of the key points from this framework.

[00:14:05] So first, I want to recognize that resilience can be a very fraught term, right? This is something that I’ve done a lot of work on, and in the past report, we decided to adopt the definition that some colleagues and I proposed several years ago for urban resilience because it is a very ambiguous term. And this definition recognizes that resilience is not just resisting change or bouncing back from, in the context of heat, both chronic and more acute heat risks, but actually bouncing forward or actively changing parts of the city that aren’t working well. And we highlight that different contributors to urban heat in combination with the efforts and strategies that are employed to address heat are ultimately going to shape a city’s resilience and therefore the impacts that heat is going to have on these different urban systems.

[00:15:00] So in our framework, we include seven principles for urban heat resilience. We adapted these from a broader set of seven principles for strong climate change planning that Sierra Woodruff and I outlined in 2020 Perspective in the Journal of the American Planning Association. And so, again, I’ll walk through some of these. So the first principle focuses on the importance of laying out clear goals for heat planning. So these are generally going to fall into two buckets which I’ve already alluded to — these are mitigation and management. So mitigation is essentially about cooling the city. This is primarily reducing how much the built environment is going to contribute to this urban heat island, adding vegetation to cool city as well. Whereas heat management is about how we actually prepare and respond to the extreme heat that we aren’t able to actually mitigate.

[00:16:01] And so we argue that cities really need to be thinking about both of these. They need goals and objectives for both, and then they need corresponding metrics that they’re going to actually track over time, right? So some citywide metrics for mitigation could look like something like reductions in land surface temperatures, which are really quite readily available from satellite imagery or increases in the percent of tree canopy cover across the city or across specific neighborhoods. Since there’s been a lot of work showing that vegetation cover, shade and heat are quite related to each other. On the heat management side, cities might want to track, for example, and reduce heat related deaths, hospitalizations or illnesses — just again as a couple of examples.

[00:16:47] Now, as we start discussing these goals right, it’s already probably clear that communities are going to need information on current and future heat risk. And this is our second principle — what we refer to as having a strong fact base for urban heat. And a challenge here is that really there are a lot of different types and sources of information that are potentially relevant for communities. Because as I’ve always alluded to, there’s different factors that are actually contributing to the overall urban heat risk. And these risks are changing rapidly, right? So communities may want to try and combine different sources actually into a single platform or portal. For example, Pima County in Arizona has tried to do here with their resiliency planning web tool, which includes, for example, information on social vulnerability, as well as physical heat exposure based on land surface temperatures.

[00:17:43] So what information are planners using now? What does the current fact base broadly look like? Well, in our survey, we asked about this and found that over 70 percent of the respondents said that they were using some kind of heat information. And so the most commonly used were reportedly vegetation maps, a heat index, and historic temperature data. Future scenarios on the other side were the least commonly used, and we asked planners whether they didn’t use the information because they didn’t see it as useful or because it wasn’t available, with the idea being that actually this latter category are information gaps, which researchers and other climate service providers have an opportunity to actually fill and help communities with. So that’s what you’re seeing here.

[00:18:32] And so what were these gaps? Well, planners said that they were included future scenarios, land surface temperatures, air temperature data and heat vulnerability maps. And I think this is interesting because actually some of these already exist for quite a lot of communities. So in particular, land surface temperatures, are, as I mentioned, already, quite readily available from satellite data. For example, the Trust for Public Land has actually created heat severity maps for every city in the U.S. based on Landsat satellite — land surface temperature data. And these can help too show communities where some of the relatively hotter neighborhoods are or to determine how much hotter a particular city is maybe than surrounding areas. So helping to quantify this urban heat island. And so this could guide policies that have as their aim to actually reduce the island.

[00:19:23] But I think it’s important to note that land surface temperatures are not the same thing as the heat that you or I actually experience in a particular place. So land surface temperatures really shouldn’t be the only information that communities use for heat planning, ideally. So for example, if you’re trying to plan out specific mitigation strategies in a particular neighborhood, say, to keep residents cool, then land surface temperatures are probably not actually going to be the most useful. Instead, you might want to really try and measure your air temperatures, or even more ideally mean radiant temperature, which is influenced a lot by shade. It’s a reflection of also the actual radiation — solar radiation — that you’re receiving, and it’s a lot closer to what people feel. But unfortunately, of course, there are so often tradeoffs, right? It’s more complex to measure. And so this recent study that I’ve put up here by Kelly Turner and colleagues showed that actually land surface temperature from satellites’ data and mean radiant temperatures were not always very closely related in particular neighborhoods and really kind of cautioned against using this remotely sensed data for very localized mitigation planning.

[00:20:39] And then, of course, this is all on the mitigation side. Then when you want to try and tackle management strategies you need information about who is at risk. And this is really the goal of heat vulnerability indices like this one, which is produced by the NIHHIS or the National Integrated Heat Health Information System (NIHHIS). The key point I want you to take away from all of this is that the different information about heat, a different package maybe of fact base is going to be needed and useful for different heat related goals and for different planning scales.

[00:21:11] All right. Moving into the next principle, what do you do with this information? So there are different strategies for achieving heat mitigation and management goals that you’re going to use this information for. In our framework, we’ve categorize them and I’m not going to have time to go into each of them in depth and talk about the evidence and specifics. But I do want to give you a little bit of a rough sense of what they are. So on the heat mitigation side, we’ve identified four subcategories, which we tried to visualize them in this graphic here, of what a community that actually was employing them might look like. So, with respect to land use, we see that open spaces have been conserved. Surface parking is minimized. Buildings are going to be oriented and shaped in order to maximize shade and increase ventilation. They’re going to be also designed so that they would maximize shade for pedestrians specifically and also to increase energy efficiency, which reduces waste heat. A variety of shade structures are included and shown here, which would shelter pedestrians, park users, as well as those waiting at transit stops. The streets have been covered in cool pavements. And there’s different sorts of urban vegetation and water features incorporated into the site design. Additionally, waste heat is further reduced in the community through promotion of bicycling and walking. So reducing car use. So these, again, are an example of some of these heat mitigation strategies and what they might look like.

[00:22:40] On the heat management side, strategies would include policies and programs that focus on energy systems, particularly ensuring that residents — all residents — have access to reliable and affordable indoor cooling that’s also efficient. Strategies geared towards reducing personal exposure to heat, enhancing public health measures and also preparing for heat emergencies. So in the community, again, pictured here, ideally you would have a resilient electricity grid that’s powered by different forms of renewable energy. In this case, we’ve shown rooftop solar and wind. You have buildings that are air conditioned shade, structures, trees and different sort of umbrellas help to reduce personal heat exposure for pedestrians and children outdoors. You would also have regulations governing how people can be outside and working outdoors and making sure that they’re safe as well as in schools. You have public health interventions, which also could include informational signage and water distribution if needed. And then the community has a resilience hub, which can serve as a shelter, a cooling center, so to speak, for people who need it during a particular heat emergency.

[00:23:54] So I’ve laid out some of the ideals. Which of these strategies are cities currently employing? Well, according to our survey, one point here is that around 90 percent of the planners said that they had implemented one or more heat strategies. The majority of them said that they were implementing urban forestry, emergency response strategies, weatherization programs, and manmade shade structures. So these were all used in the majority of communities. So we do see a mix of mitigation and management strategies, but we do see that very few communities — really a minority — actually had regulations or dedicated staff for heat and also a minority working heat vulnerability assessments. So there is clearly a lot of room to really scale up efforts.

[00:24:44] Now, moving into the fourth principle here, because of how complex and varied urban climates and cities are, it’s really difficult to predict exactly how effective each of these strategies are. Because it really varies by climate, it varies and how they’re implemented, right? But communities should try and recognize some of these sources of uncertainty and ultimately try and prioritize strategies, we argue, that would be beneficial under a variety of different features if it’s possible at all. So in other words, this means really trying to prioritize first some of these no regret or lower threat strategies.

[00:25:24] For example, this is a green infrastructure or low impact development installation on ASU’s campus here, which is designed to provide shade for students outside the student union. But on the rare occasions when it does rain here in the desert, this installation also helps to capture a stormwater and reduce flooding in this high traffic zone on campus. So I think this is one of these things that has multiple benefits. Great. So we can all agree that we should have goals, information and strategies, right? But who’s actually going to do it? So this brings us to the fifth principle, which is the importance of really coordinating heat action.

[00:26:04] So I’ve already said that no one really at present owns heat in most places. Heat mitigation seems more in line with what a lot of urban planners and designers are thinking about. Heat management on the other side tends to be more the domain of emergency managers, public health officials and departments. But at what level of government is this a county problem? Local city problem, right? Should the federal government be taking action and which plans should really be addressing and dealing with heat within a city? Should he be integrated across all plans? Or should their community start developing standalone heat resilience plans? Well, we asked about this in our survey when it confirmed really that he planning is currently quite fragmented, so the majority of planners did say that they were addressing heat and at least one of their plans, but no one plan category addressed heat in the majority of communities.

[00:27:02] So the most common place to address heat or sustainability, climate and resilience plans, perhaps not that surprising, but only about thirty 36 of our respondents said that they were addressing heat in these type of plans. On the flip side, zoning codes and regulations were least common. And that’s a little bit unfortunate because often these tend to have some of the strongest teeth, right? Or most likely that they’re going to be followed and implemented. It’s also interesting to note I think that only a small minority of planners said that their communities were actually integrating heat into their hazard mitigation plans, which does seem like a fairly obvious place where it could be addressed.

[00:27:40] So because cities really rarely have these standalone heat plans at present, and we can clearly see that heat strategies are integrated into different types of plans. We argue that we need to think about a community’s plans as an integrated network that’s going to collectively shape heat risk and resilience. So just to give you a little example, a city’s Parks and Recreation plan might call for new green space that helps to mitigate heat. The Climate Action Plan might also work towards heat mitigation through calling for new vegetated roofs or walls — new green infrastructure. But then we have a transportation plan that’s adding new surface parking lots and calling for road expansions that are actually going to exacerbate the urban heat island and are ultimately going to negate some of these cooling effects from other plants.

[00:28:29] So with support from NOAA’s Climate Program Office — their Extreme Heat Risk Initiative — Ladd Keith and I are currently working with Phil Berke, a planner at UNC Chapel Hill, as well as the American Planning Association, to develop, essentially, a step by step process that communities can use to identify some of these contradictions in plans like this that I talked about and really to assess how the different policies that are planned in these different community plans. For example, new development or new green space, how they would affect heat in different parts of the cities. Because what we found going through plans is that there’s a lot of discussion about new development and green, et cetera, but it’s rarely actually explicitly connected to what impact it will have on heat.

[00:29:19] And so this project — what we’re calling the Planned Integration for Resilience Scorecard for Heat or PIRSCH — builds on the original plan Integration for Resilience scorecard that Phil Berke and his colleagues developed for thinking about flooding and how it was integrated — how flood risk was integrated across community plans. How does it work? Well, basically first, you identify the different plans that are shaping land use and the built environment in a community, this network of plans. Then you read through those plans, you identify the spatially explicit policies, you categorize and roughly score them based on whether they would increase or reduce vulnerability to heat or heat risk. And then you add up those scores so that you can get an overall sense of the cumulative impact of the full network of plans on different neighborhoods, so you actually map them out. And so this gives you a sense of which neighborhoods are being prioritized for policies, which ones are future plan developments likely to increase heat in, where are they likely to reduce heat? And you can also compare these with exposure or vulnerability maps to try and get a sense of whether plans are targeting the highest risk areas.

[00:30:28] So we’re actually currently piloting this for five cities. But we’ll also be developing a guidebook so that other communities can apply the same approach to try and assess their plans and their impacts on heat. So if communities are going to avoid contradictory policies and if heat planning is going to be successful, it’s going to require coordination. And this is going to include different levels of government as well as genuine engagement with communities. So I put up here a picture of one example of a project that I think really tried to do this here in Phoenix. I was not directly involved with this, but it was the nature’s cooling systems project where they worked with several high heat risk communities to really develop and co-create heat action plans through a series of participatory workshops.

[00:31:13] And as further evidence of this need for multilevel governance on heat, I think it’s just worth noting that when we asked our survey respondents which level of government should be responsible for heat, ultimately they really said that it ran the gamut right from the local level, all the way to the federal level that everyone had a role to play. And I also believe that heat justice, I hope that’s come through here, needs to be central to planning for urban heat. And that means not just making sure that heat risks and strategies are going to be fairly distributed, but also recognizing that they haven’t been historically. And then customizing strategies to actually really meet the different needs that these communities have. So community members should be part of this process. They should be helping with developing research and implementing these strategies, even if this engagement takes time, as I think the nature’s cooling systems project did show.

[00:32:07] And so I think that planning for heat equity, like planning for resilience more broadly, is going to require distributional, recognition, and procedural equity. And one concern I have is that in my research on resilience planning more broadly, I found that really there’s a lot less recognition and procedural equity in plans than there is focus on distributional equity. And even that is quite variable and somewhat spotty. So I would just say that let’s please not make this mistake — the same mistake with heat planning now.

[00:32:40] And finally, last but not least, given the urgency of the threat, I think we need to make sure plans actually get implemented. Especially because the science of urban heat is evolving quite rapidly. It would really be beneficial to actually monitor and evaluate whether strategies work. And so here I see a lot of opportunity for researchers to actually partner with communities to do this monitoring. Just as an example here, some of my colleagues have been working with the city of Phoenix to try and monitor a cool pavement pilot project and see how it’s working over time. So I think we should have more really. And finally, I think it needs to be acknowledged that planners really do see a lot of barriers to advancing heat resilience. In our survey some of the most significant were those related to human and financial resources as well as political will. So I do think that we all have work to do in raising urban heat on the agenda and actually making sure that we’re dedicating resources to addressing it.

[00:33:41] So I know I’ve gone through our heat resilience framework pretty quickly here. There is obviously going to be a lot more detail in our over hundred page report, which I’m happy to report will be published at the beginning of April and freely available. And you can also find more information on the survey, as well as some of these other studies that I’ve talked about is listed here. So I’ll just end by acknowledging that all of this work has been very collaborative, very grateful to my co-authors, as well as my institution and those who have come before me here. So thank you and I’m happy to take any questions — which I see there are a couple in the chat.

“Urban heat resilience” discussion with Julian Agyeman

Julian Agyeman: [00:34:21] Well, Sara, thank you so much. That was a fantastic tour de force and a call to action. Yeah, amazing. And you know, it’s interesting just this difference between mitigation and management, simple things that sometimes we miss this. And one thing that sort of strikes me is we’ve had the last 42 years of neoliberal privatization, deregulation — that’s the context in which this super coordination is going to have to happen. We’re not used to it in many ways. I used to work in local government in London, in the 80s, and we were still fighting against that neoliberal wave. But now, 40 years on, it is pretty much complete. How do we get to the situation where we can do what we need to do?

Sara Meerow: [00:35:17] Yeah, I mean, I think that’s a great question. I think what communities have been doing, which is trying to be creative and finding partnerships in getting resources where they can. So I think at the, maybe, say like, government level, that trying to be creative and find resources where you can work together, right? And I think that’s where making sure that we’re not working in silos because resources are so limited that let’s make sure that, for instance, if we have a storm water focused organization, that they’re also communicating with people who are thinking about heat to make sure that if we have the opportunity, we can plan green infrastructure, say in places that are also high risk for heat, something like that. So I think just using things as efficiently as possible and actually coordinating things, at least making sure that we’re not working at cross-purposes, right? So that’s one.

[00:36:06] I think the other thing is really just spreading the word and making it impossible to not take action. I think that we are in some way — in some places, I think, starting to reach this point with heat. So it seems like here in Phoenix, heat is a big enough concern that the city created a dedicated office of heat mitigation and response and has a dedicated heat officer that’s actually funded by the city, which was the first one to do that. And I think it’s because it is such a big issue here. People are worried, they’re worried about these heat deaths like I showed and the trends. They’re worried about impacts to the economy and the future of the city. And so I think that if it is urgent enough, there’ll be some action. But I still I do see the challenge right, and I think it’s just going to require resources to really deal with this. And I think it has to be coordinated and that is challenging and a highly decentralized, privatized context.

Julian Agyeman: [00:37:01] Ok, so I’m going to take moderator privilege and have two quick questions. Who in the U.S., which city in the U.S. do you think is moving in this direction most comprehensively?

Sara Meerow: [00:37:13] Yeah, that’s a great question. I mean, I feel like it’s hard to not be biased a little bit, but I do feel like Phoenix is really a leader in this space as the first city that actually has created this dedicated office that is funded by the city and is actually combining mitigation and management. I think that seems very promising at a city level. I think there’s other cities now that have chief heat officers. So like Miami-Dade County, has one, but that is funded by a philanthropic organization. So it’s not coming from the city, per say, I think may happen in the future. City of Los Angeles is also now planning to have a heat officer as well. So I think that they are probably going to be becoming a leader in the space as well. So those are two that I guess I would point to, and I think often it’s out of necessity. Obviously, it’s Phoenix being one of the hottest cities in the country.

Julian Agyeman: [00:38:07] Ok. And the second question was globally, I mean, we heard that Athens in Greece has a heat officer. I mean, our cities globally. Sydney, Australia. I mean, are these changes happening in those cities as well?

Sara Meerow: [00:38:21] Yeah, I think my sense is yes, although I admittedly have been focusing much more on what the current state of affairs is in the U.S., I haven’t done as much research internationally. I would like to in the future, and I am very interested in seeing how this — what we found for the U.S., how it compares more broadly. But yes, I do think certainly there have been other cities that are thinking about this in the wake of there’s been some pretty horrific heat waves in Europe in recent years, and that has led to a lot of government actions. France had a pretty big national plan in the last decade to try and address and reduce heat deaths. But my understanding is has been pretty successful. I haven’t studied it personally, but I think, yeah, so I think, yes, we’re seeing more and more of this, and I think people are — just the media attention that all of this is received, right, I think is a reflection of the fact that people are worried about this.

Julian Agyeman: [00:39:20] Great. Ok, let’s go to questions. Aggeliki from our department is asking, “did you quantify heat reduction through the implementation of different plans or did you have the numbers taken from other studies?”

Sara Meerow: [00:39:33] Yeah. So just to clarify, we’re not quantifying how much each of these policies are actually reducing heat. I think that would be far too difficult given often how not detailed these strategies are in plans — it would require complex modeling. So but we’re we’re definitely not there. All we’re actually doing is just scoring them either one, if it would reduce heat risk, if we think it would reduce heat in the built environment, of negative one if we think it would add to heat, and then we’re actually also scoring something that hadn’t been done in the flooding applications of the planned integration for resilience, is we’re flagging all of the policies that we believe would have an impact on heat, but from the way it’s written, it’s not clear what it would be. We would need more detail. So we’re flagging these and scoring those as a U.

[00:40:24] And what we’re actually finding is there’s a larger number of these policies that we’re tagging as U’s than there are ones or negative ones. And I think what I still think this is important because it’s basically just showing communities, look, we think that your plan development is going to have an impact on heat and you’re not really thinking about it at the moment necessarily, you’re not making that explicit. It’s probably worth taking a little bit of time to think about this because if you have a lot of development that does increase heat in a particular neighborhood, that might be problematic in the future. So just sort of flagging this as well, that’s something to consider.

Julian Agyeman: [00:40:56] Great. We have a question from GG, “What do you think should be the level of detail of personal thermal exposure information to be useful in a heat early warning system?”

Sara Meerow: [00:41:08] I think more broadly, this question of how do we assess like personal thermal exposure and how detailed does this information need to be? I mean, it’s really hard because actually the the heat that people experience is very contextual. So different people are going to experience that differently, be impacted by it differently. And there are ways to measure and model that. But it is very individual and one of my colleagues, Ariane Middel, has done a lot of work on this and has built these special carts that try to get to that measure mean radiant temperature and taking those around and showed, for example, how different types of urban design features — how shaded areas versus cool pavement covered, but not in the sun areas, how these impact the kind of heat that most people would experience. But as I understand it, that is still not necessarily the same for every person.

[00:42:04] And so I think you’ve got to give some sort of rough indication based on the average of what is this wet bulb temperature, which is kind of a sense of like how your body is going to feel it because it adds in humidity as well as the heat. But again, like it depends if you’re in the shade or you’re in the sun, how things are going to feel and everything. So I think trying to get people to understand this, that there are different ways of measuring heat and these matter and land surface temperature is different than air temperature, which is different than, say, mean radiant temperature. I think, yes, we do need to have that.

[00:42:35] And I think trying to approximate what it is that people will feel is really important. And so that’s why I think an emphasis on — there’s been some calls to talk more about wet bulb temperature, right, as opposed to just air temperatures, because that is important, adding in that humidity part. So yes, I think this is really important in trying to get people to understand — putting it into terms that people can understand, how long if you’re exposed to this, how long can you be outside and exposed to this temperature before you’re likely to start getting heat stroke or something like that. But again, that’s not — I haven’t done as much on those individual level exposure and public health communication aspects, but I think they’re really important.

Julian Agyeman: [00:43:14] You have a question from Laurel Williams, “Can you speak to the resources versus benefits of programs like white pavements in terms of felt heat in neighborhoods.”

Sara Meerow: [00:43:25] Yes, the cool pavements are a tricky one. So this is where it gets at what is your goal for heat and that this is kind of the challenge, right? So like what some data has shown is that these cool pavements, by being more reflective, they are quite effective at reducing surface temperatures and can contribute to reducing the urban heat island overall. But for pedestrians that are walking on them at certain times of day, they can actually feel hotter because of that radiation reflecting off of the pavement. Yeah. So there’s a question of like, OK, you need to think about, well, is your goal improving the felt, the experienced temperature — the say mean radiant temperature for the pedestrians on that street, on that pavement? Or is it about overall reductions in the urban heat island?

[00:44:16] I think some of my colleagues might argue that we should probably focus more on those pedestrian’s needs, but it depends. And so that just might say, OK, there might be places where you don’t have a lot of pedestrians or any pedestrians, maybe like rooftops, it might be more important to put those kinds of reflective coatings on it. And then for places where you have a lot of pedestrians, there you might want to focus more on shade because that’s actually going to have a bigger benefit for the people who are using it. So I think it’s just the right goals and right solutions for the right place, which is tricky, right? Of course, we all want simple solutions, and I think it’s often not the case that those exist.

Julian Agyeman: [00:44:55] Ok, we have a question from Lucas Belury who asks, “What existing adaptive coping strategies do we already see from folks living under the threat of heat? And then how can we, as policy makers, from city planners to governors, advance those existing practices?’

Sara Meerow: [00:45:12] That’s a great question. I haven’t done as much again on individual actions. I tend to think more at the city level, but I think the most common adaptation coping strategy for heat is cooling technology — air conditioning, fans — they’re very effective, and that’s what most people use is getting out of the heat and into those places. But not everyone has access to it, right? And I think that’s a really important point from when we think and prioritize heat equity, is to say yes, of course, if you add a lot of inefficient air conditioning to a city, it is going to add waste heat and it’s going to ultimately make it hotter, contribute to climate change. So that can be problematic. But for some people, we need to provide cooling. And yes, we can try to make those efficient. We can try and make those as efficient as possible. But I think it still needs to be done because we should not be letting people die from heat. That’s unacceptable, I think. And one heat death is one too many, really.

Julian Agyeman: [00:46:14] Ok. Bryn Lindblad asks the question, “Elected officials have a capital bias — they like putting in new things, but there’s a shortage of funds for maintaining green infrastructure. Any recommendations for resourcing the maintenance of green infrastructure?”

Sara Meerow: [00:46:30] That’s a great point. I completely agree. And this is a big issue. I mean, I don’t have a perfect answer there other than to say that that needs to be built into the initial plan. We should not be implementing green infrastructure if we don’t have the resources and the funds to maintain it over time. And I think that just needs to be built into that initial cost calculation and into any kind of cost benefit calculation. So that would be the key is I think we just need to do. It in terms of how it’s done, Yeah, I mean, I think that’s going to vary and what the exact funding mechanisms are for it.

Julian Agyeman: [00:47:06] We’ve got another question, “What current action is being taken policy wise at the federal and state levels to address the racial and class bias surrounding many zoning laws and laws related to climate change that allow Black, Brown and poor and low-income neighborhoods to be built in ways that aren’t heat and climate resilient?

Sara Meerow: [00:47:26] Yeah. So this is actually finally receiving some attention at the federal level. I’m not as familiar with all of the state level actions, but I think there has been a lot of discussion in some of these big bills that have been being discussed — some paused, some have been, with the infrastructure bill, others with the Build back Better, a little bit more stalled at the moment. But discussions about building in things for, for instance, trying to work towards having greater tree canopy equity programs to address some of these disparities, definitely. There’s been a lot of discussions about environmental justice as well, but I think I don’t necessarily know of exact laws to tell you that are addressing these exact disparities. But I think there’s certainly a lot of discussion and recognition of it, and I think more effort to try and address it, but probably needs to be more.

Julian Agyeman: [00:48:24] Joel Robinson wants to go global again. “Has there been much comparative research on urban heat mitigation strategies in comparable climates around the globe? What might American planners learn from planners working on these issues in different climates? We acknowledge that heat is a global issue, but the research seems to be so context specific, and it makes me wonder what kinds of knowledge exchanges can promote a more global approach to the crisis.” Great question, Joe.

Sara Meerow: [00:48:51] Yeah, that is a great question, and I think there are opportunities. I think there’s been a lot more — so the area that I’m most familiar with is the green infrastructure as a heat strategy as well as providing other benefits, right? And I think there is some exchange of information across borders and for example, looking at arid cities and communities and very much look at, for example, work that’s been done in Israel or in Australia to inform places like Phoenix or vice versa when it comes to that. Because honestly, that’s more comparable in terms of how green infrastructure is actually going to work than it is to look at what New York City or Philadelphia are doing and compare that to Phoenix.

[00:49:35] So I do think thinking about more about where are there comparable climates and risk profiles and then trying to learn across those. I think there’s a lot of benefit to doing that. I think one potential barrier there, though, I mean, I think there is some of that definitely happening. And also across like these — there’s so many more of these city networks now at a global scale where you have these, say, chief heat officers or chief resilience officers in different cities that are part of the former one hundred Brazilian cities network or the C40 cities, which are getting together and exchanging information and creating reports and plans and things that maybe get looked at by these other cities.

Sara Meerow: [00:50:12] So I think there is that. But one challenge sometimes I’ve found is just terminology can be a big barrier, right? So just as an example: Green infrastructure. Different terms are used for it in different places. So in Australia, they have this idea of water sensitive urban design. In the UK, they have sustainable urban drainage systems. So you have WSuDS, you have SuDS. Here have LID and green infrastructure. And in some ways these are very similar. And so as I was saying, if you look up green infrastructure, arid environments, you don’t get a lot of results. There hasn’t been a lot of monitoring data. But if you add in some of these other terminology, like those water sensitive urban sites, you actually find that there’s been quite a bit of work on this in Australia. And so sometimes it’s as simple as these terminology issues that can get in the way of information exchange. So I think trying to figure out, OK, what are these terms that mean the same things in different places? And how can we learn from each other and try and speak a little bit more of a common language around these things? I think that can help this learning, too.

Julian Agyeman: [00:51:13] Great point. And we’ve got one question that I’ve just got to ask. We’re running out of time rapidly. But Sara, 30 seconds, “Does density increase urban heat?”

Sara Meerow: [00:51:24] Not necessarily. I think if it’s done well, it can actually really improve it. If you orient buildings and shade buildings so that they provide shade, they maximize efficiency, then don’t have as much cars. You have less waste heat, right? I think the density can actually be an improvement. It really depends. We should not assume that dense equals that it’s going to be hotter. I think that that has sometimes been the case when we’ve just built dense places that are just covered in pavement. But we can design them in better ways to make density not necessarily a hot spot.

Julian Agyeman: [00:52:01] Great. Well, Sara, there are so many more questions — questions that I have, but what a fantastic opening presentation to the 2020 to spring colloquium at Cities@Tufts. Thank you so much. Can we show affection anyway that the technology allows us? I’m going to clap, but other people will put their little hands up or whatever. Thank you again, Sara. Good luck with tenure. If you need me to write a letter to anybody, please —

Sara Meerow: [00:52:28] Thank you, Julian.

Julian Agyeman: [00:52:29] I have a feeling I don’t need to.

Sara Meerow: [00:52:32] Thank you.

Julian Agyeman: [00:52:32] Next colloquium is Sara and our’s friend Linda Shi. It’s on February the 23rd. Linda Shi’s from Cornell. She’s talking about “Collective Land governance for a Changing Climate.” There’s a theme emerging here, so —

Sara Meerow: [00:52:45] Yeah, she does great work. That’s guaranteed to be a good talk.

Julian Agyeman: [00:52:48] It will be excellent talk. Thank you, everybody. See you on the 23rd.

Tom Llewellyn: [00:52:55] We hope you enjoyed this week’s lecture. You can access the video, transcript, and graphic recordings of Sara Meerow’s presentation on Shareable.net. As Julian mentioned, our next live online event is Wednesday, February 23rd, when we’ll feature Linda Shi’s lecture: Collective Land governance for a Changing Climate. Click the link in the episode notes to register for a free ticket. And if you can’t be there next week, you can always find the recording right here on the podcast.

[00:53:22] Cities@Tufts Lectures is produced by Tufts University and Shareable with support from the Kresge, Barr and Shift Foundations. Lectures are moderated by Professor Julian Agyeman and organized in partnership with research assistants Parri Sheinbaum and Caitlin McLennan. “Light without Dark” by Cultivate Beats is our theme song. Robert Raymond is our audio editor. Zanetta Jones manages Communications. Allison Huff manages operations. Fraulein Anke made the graphic recording. Caitlin McLennan created the original portrait of Sarah Meerow. And the series is produced and hosted by me, Tom Llewellyn. Please hit Subscribe and eave a rating or review wherever you get your podcasts and share it with others so that this knowledge can reach people outside of our collective bubbles. That’s it for this week’s show. Here’s a final thought:

Sara Meerow: [00:54:08] We need stronger heat governance right now, and when I say heat governance, what I mean are the actors strategies and processes, as well as institutions, to actually guide decision making for both mitigating heat in cities. So reducing heat and managing the impacts.