Urban agriculture has a long and diverse history throughout the world. Its health, social, and economic benefits for communities have been the subject of many studies and advocacy efforts seeking recognition of urban food production as a legitimate use of city space and as “real” agriculture. In the US, the past decade has seen policy support for urban food production expand at multiple scales of governance.

At the same time, new forms of high-tech, commercial urban agriculture have emerged, often funded through private investment and venture capital. Understanding the implications of these shifts for racial and economic inequity, within the broader US context of social inequality, is important in designing and implementing more socially just urban agriculture policies. In this talk, Kristin Reynolds discusses recent evolutions in urban agriculture practices and policy, their implications for racial and economic equity, and her current work to inform more socially just urban agriculture policy through her Food and Social Justice Action Research Lab.

About the Presenter

Dr. Kristin Reynolds is Chair and Assistant Professor of Food Studies at The New School in New York City. As a geographer with expertise in international agricultural development, she is interested in understanding how uneven power dynamics in the food system originate and articulate at different community and geopolitical scales. Using critical and participatory action research, her work focuses on informing the creation of more socially just food systems through scholarship, policy, and activism.

Her current research areas include: urban agriculture policy in the US and, France; small-scale heritage grain production and food sovereignty in Eastern France; and inequities experienced by immigrant and racialized farm workers in Southern France. As a part of her scholarship and food systems work, Dr. Reynolds collaborates regularly with community-based food and environmental organizations and supporters.

Dr. Reynolds is an Affiliated Faculty with the Yale Center for Environmental Justice at Yale School of the Environment; a Research Associate at the European School of Political and Social Sciences in Lille, France; and a Specialist with the US Fulbright Program. She holds a Ph.D. in Geography and M.S. in International Agricultural Development from the University of California, Davis.

About the series

Shareable is partnering with Tufts University on this special series hosted by professor Julian Agyeman (Co-chair of Shareable’s Board) and Cities@Tufts. Initially designed for Tufts students, faculty, and alumni, the colloquium has been opened up to the public with the support of Shareable, and The Kresge Foundation.

Cities@Tufts Lectures explores the impact of urban planning on our communities and the opportunities to design for greater equity and justice.

Register to participate in future Cities@Tufts events here.

Listen to the Cities@Tufts Podcast (or on the app of your choice):

Urban Agriculture, Racial and Economic Equity Transcript

[The timestamps in the transcript correspond with the audio version of this lecture.]

Tom Llewellyn: Hey, Tom here, just wanna make a quick ask before we get started. If you’ve been enjoying this show and you wanna help us grow our audience and reach more people, one of the most helpful things you can do is to leave us a five star rating and review on Apple Podcasts or just the rating on Spotify. It’s super easy to do and will only take a few moments of your time, but it will make a huge difference for us, because the algorithms on these apps are designed to push forward shows that get more ratings and reviews. If you’re listening on either of these platforms you don’t even have to pause the show to rate it. With your support we’ll be able to keep this project going, so, thanks for helping us out. And now, on with the show.

[music]

Kristin Reynolds: We think about urban agriculture as the growing of food and non-food crops like flowers for example and the raising of livestocks in and around cities, but also its integration into the social, economic, and ecological fabric of the urban landscape. Urban agriculture may not produce the highest and best use when we are talking about the urban planning in sense of the term in terms of the use of urban space, but it produces multiple and intersecting benefits. We talk about these in categories such as health benefits, increased access to healthy food, opportunities to spend time outside, social benefits in terms of interacting with neighbors that one might not otherwise interact with, youth development, economic benefits like food affordability, and in the case of organizations that create jobs, creating some jobs in the community, and then ecological, increasing biodiversity, helping to reduce urban heat island effect. So we talk about these intersecting benefits as part of the overall picture of urban agriculture and what it brings to the city.

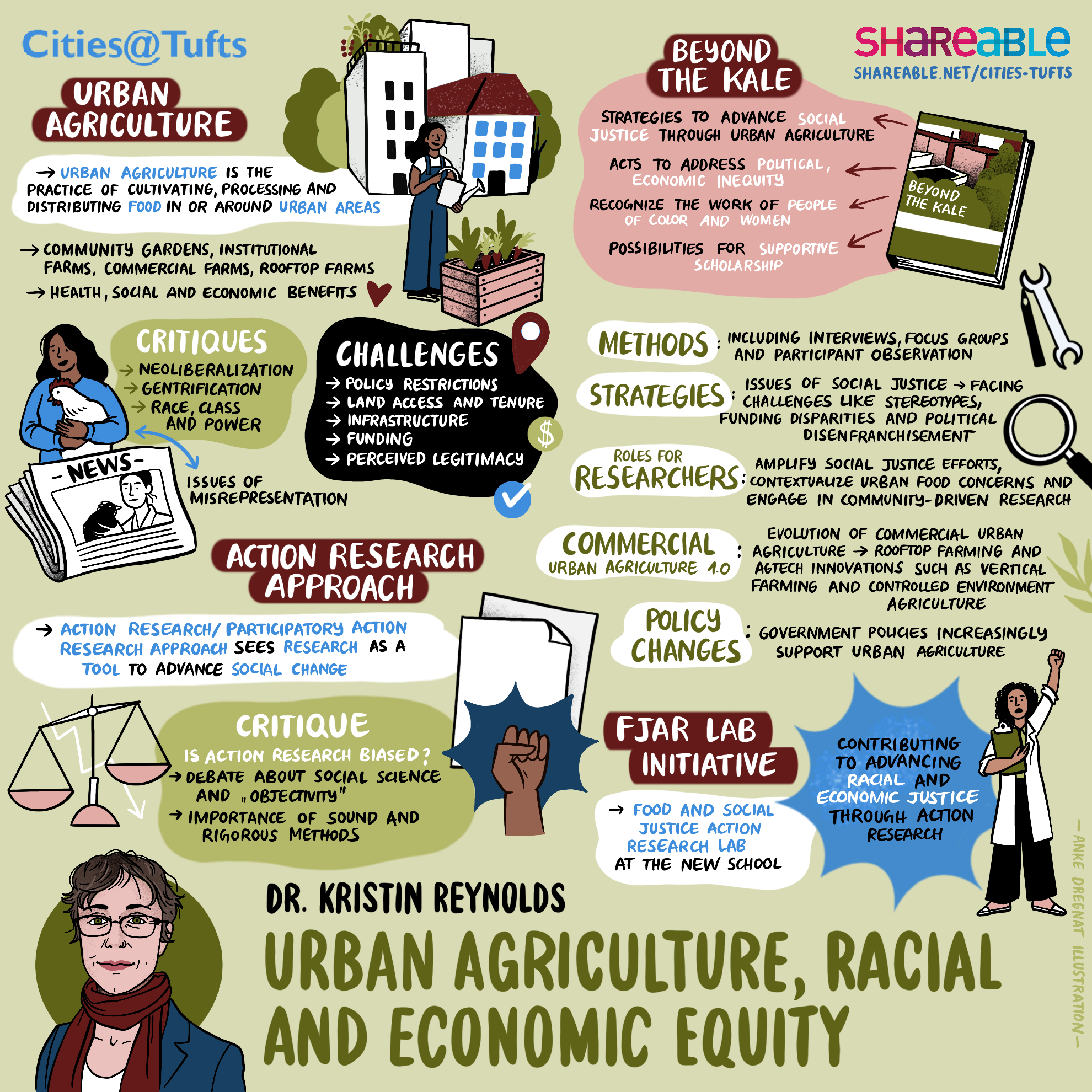

Tom Llewellyn: Welcome to another episode of Cities@Tufts brought to you by Sharable and the Department of Urban and Environmental Policy and Planning at Tufts University with support from the Barr and Shift Foundations. Today’s show features a lecture from Dr. Kristin Reynolds who discusses recent evolutions in urban agriculture practices and policy, their implications for racial and economic equity, and her current work to inform more socially injust urban agriculture policy through her Food and Social Justice Action Research Lab. In addition to this podcast, the video, transcript, and graphic recordings are available on our website, just click the link in the show notes. And now, here’s host of Cities@Tufts, Professor Julian Agyeman.

Julian Agyeman: Welcome to our Cities@Tufts Virtual Colloquium. I’m Professor Julian Agyeman and together with my research assistant Deandra Boyle and Mariam Bakari. Under our partners Shareable and the Barr Foundation, we organize Cities@Tufts as a cross-disciplinary academic initiative which recognizes Tufts University as a leader in urban studies, urban planning, and sustainability issues. I’d like to acknowledge and we would all like to acknowledge that Tufts University’s Medford campus is located on Colonized Wampanoag and Massachusetts traditional territory. We are delighted today to host my friend and longtime colleague, Dr. Kristin Reynolds, Chair and Assistant Professor of Food Studies at the New School in New York. As a geographer with expertise in International Agricultural development, she’s interested in understanding how uneven power dynamics in the food system originates and articulated different community and geopolitical scales.

Julian Agyeman: Using critical and participatory action research, her work focuses on informing the creation of more socially just food systems through scholarship, policy and activism. Dr. Reynolds first book, and I gotta say people here, this is my favorite book title ever, period. Beyond the Kale: Urban Agriculture and Social Justice Activism in New York City, which she co-authored with Nevin Cohen, examined the work of community-based activists to advance social justice through urban agriculture and roles that research and scholarship can play in such initiatives. A forthcoming book, Radical Food Geographies: Power, Knowledge and Resistance, co-edited with Colleen Hammelman and Charles Levkoe, will be published next year. Kristin, a Zoomtastic welcome to Cities@Tufts, over to you.

Kristin Reynolds: Thank you very much Julian for that lovely and glowing introduction. I’m so happy to be here and thank you for inviting me to speak with you all today. I also want to begin by acknowledging that The New School, located in Manhattan, is located on traditional and unseated Lenape territories and acknowledging this part of the social justice practice that I attempt to employ in all of the work that I do as a scholar, as educator. I’m very happy to be here with you all talking today about some of my work on urban agriculture and using action researchers approaches to advance racial and economic equity. I’ll give some background to how we think about urban agriculture in this field, a little bit about what I mean when I’m talking about action research. And then provide a few, three examples from some of my past. And thank you for the shout out on Beyond the Kale and current work in this area.

Kristin Reynolds: First of all I want to say that there’s not one singular history of urban agriculture in the United States. There are in fact multiple histories that intersect with each other. I wanna give some highlights that will be good background for the rest of the talk. To begin, what do we mean when we talk about urban agriculture? In the field, that is in the scholarly field, but I think also in the literal field, you think about urban agriculture as the growing of food and non-food crops like flowers for example and the raising of livestocks in and around cities but also its integration into the social, economic, and ecological fabric of the urban landscape. Urban agriculture may not produce the highest and best use when we’re talking about the urban planning sense of the term in terms of the suburban space, but it produces multiple and intersecting benefits.

Kristin Reynolds: We talk about these in categories such as health benefits, increased access to healthy food opportunities to spend time outside, social benefits in terms of interacting with neighbors that one might not otherwise interact with, youth development, economic benefits like food affordability, and in the case of organizations that create jobs, creating some jobs in the community, and then ecological, increasing biodiversity, helping to reduce urban heat island effect. So we talk about these intersecting benefits as part of the overall picture of urban agriculture and what it brings to the city. On this infographic, which comes out of another project that I was part of, we see some ideas of what the forms of urban agriculture are. And so I think community gardens are usually most familiar to people, folks growing for themselves or their families or their extended community on a small plot.

Kristin Reynolds: Beauty farms where people are working together, often these are youth projects, growing food for sale or even to give away in low income communities. Institutional farms and gardens, like those at hospitals or school gardens, where these are used for therapeutic and or educational purposes, as well as growing the food. And then commercial farms, which I’ll talk more about a bit later, but as the name suggests, farms in cities that are selling their products. So that’s kind of an overview of what we talk about when we mean urban agriculture. So, as I noted, there are diverse histories that get told about urban agriculture in the United States. So I’ll start with this narrative, which is that there are centuries of examples of people growing food in cities.

Kristin Reynolds: The late 19th century is the pinpoint that is often placed on government support for urban agriculture, with the Pingree potato patches. It was land that was provided to urban residents by the mayor of Detroit, seeking to address food insecurity in the wake of economic downturn, as well as to quell potential unrest. In the early 20th century in New York, progressives of that era, who were fearing the loss of what they saw as good values in the wake of increasing industrialization and loss of contact with nature, created children’s gardens that brought children. And you might note from this picture, rather well-to-do children outside to engage in green work, to learn about agriculture and food, and to be outside. In both World Wars, in the United States, as well as other countries, including the UK, the federal government created a program… Well, programs, including Victory Garden programs in which the government provided education and tried to promote the use of gardening in cities in order to divert rural agricultural products from urban consumers to the Allied war effort.

Kristin Reynolds: A statistic is that at one point in the ’40s, 44% of vegetables consumed in the United States were grown in cities. If you’re interested in government videos, I encourage you to look up Victory Garden videos and you’ll see lots of very convincing educational footage from the time. And then, so these were largely government-driven urban agriculture initiatives. And in the ’60s and ’70s began a new era of urban agriculture and urban farming that was more grassroots-driven. Here I put a picture of the Boston Urban Gardeners, a group that was created in the 1970s to build gardens in the city of Boston. This also took place in New York. So for those who are not familiar with New York, these are the five boroughs, Manhattan, the Bronx, let’s go this way, Queens, Brooklyn, and Staten Island.

Kristin Reynolds: And so in other cities like Boston, during this time period, there was economic crisis, fiscal crisis, globally, as well as in the city’s budget, and unscrupulous landlords who would burn down apartment buildings so they can collect insurance money. So this, combined with racist policies of the time, created a situation in which there were lots that were seen by some as vacant, though that term, and we can discuss later the contestation of that framing of land, but that there were lots that might have started out looking like this. That gardeners, farmers, individuals living in the communities, or not living in the communities, kind of took these spaces over and started to make community gardens on them. At that time… So this was the beginning of the grassroots movement for urban gardening in New York. The city government followed suit creating the Green Thumb Program, which is part of our New York City Parks and Rec Department, and to this day manages the majority… Well, a large number of the community gardens in New York City.

Kristin Reynolds: And at this time, there were also federal HUD block grants that provided funding for gardens in low income communities, which brings us to the reality that many of the gardens in New York City are located in low income neighborhoods. Skipping through a few decades, gardens, I talked a little bit about the social benefits but gardens are also used and continue to be used, not only as places to grow food, but also as spaces where communities can continue to live their cultural practices such as this example of a casita in a community garden in the Bronx, casitas being among other cultures, also using these small structures in a the garden as a place for social gathering. And this is a Puerto Rican run garden. So those are a few examples of urban agriculture and its history in the United States.

Kristin Reynolds: But I’d like to always feel it’s important to introduce some critiques to urban agriculture and then I’ll talk a little bit more about the second narrative. So, first of all, that it is true, this part is not a critique. It is true that urban farms and gardens often sell their products in the city, and often that is in an effort to provide food access to those who can’t afford healthy and fresh vegetables. Now the critique, and I think this critique is more relevant probably in the scholarly world than it is on the ground grassroots community world but it’s important to highlight nonetheless, is a question of whether using commercial sales of garden products in the city to address food security is just representing neoliberalization. That is the supporting the rollback of government, social service, and social safety networks. Or addressing deeper issues, that surround food security by simply selling food. So here’s one critique that exists.

Kristin Reynolds: A second critique is that, because of the fact that gardens can increase property values, urban gardens when they’re created in neighborhoods that are low income, can end up pushing out a long time residents. So this is a critique that’s taken very seriously. This one is certainly not just an academic debate. And then finally, I want to talk about the politics of representation, as they relate to race, class, and power in the system. So what you see on the screen is the image of an article that was published in New York Magazine in 2010, called, What an Urban Farmer Looks Like.

Kristin Reynolds: And in this article there were beautiful photographs of urban farmers, most of whom were white folks, which doesn’t represent the reality of urban farming in New York City. And this was problematic in terms of how it’s presented. What is this like up and coming trend in New York. I always want to be fair when I talk about this, that many of the gardeners that were featured in this piece, including the person that you see on the slide, were very vocal about the fact that they didn’t think that this represented New York City urban agriculture, that this needed to present in more diverse picture. And so that was important. And coming back to the point about representation, when we see these kinds of narratives that say, here’s what an urban farmer is, here large on the screen, this can reinforce political and financial inequalities, insofar as media representation can bring political policy attention, it can bring funding from large or well deep pocketed people and organizations. So these are critiques that are important to keep in mind when we talk about urban agriculture and its potential benefits.

Kristin Reynolds: And these patterns are particularly bothersome. And I’m speaking mostly today to the context of New York ’cause it’s the context that I know the best, particularly bothersome when we recognize what the reality is in terms of folks who have been leading urban agriculture in New York for its at least many decades history. It’s diverse. The city is diverse, and the leadership in urban agriculture is diverse. So these are three individuals and one group that I’ll talk a bit more about later, who are very much leaders in the food justice, environmental justice, and urban agriculture community here in the city. Yonnette Fleming, who also goes by Farmer Yan. La Finca del Sur, which is a group in the South Bronx led by women of color and their alleys, that’s how they describe themselves Ray Figueroa at the France of Brook Park, in the South Bronx, an elder Abu Talib who is one of the leaders of the Taqwa community farm in the Bronx.

Kristin Reynolds: So before moving on, I want to close out this piece about the kind of general concepts in urban agriculture by talking about general challenges. So some of these include policy restrictions in cities that, for example, disallow people to grow food in their front lawns, or grow, raise particular livestock. These are challenges confronted by urban farmers in many cities throughout the world, not just in the United States. Challenges having access to land or having land tenure in New York. There’s been a long-term debate about how long gardeners are able to use or have access to the sites, that land that is owned by the city. And for structural challenges like accessing water are also something that is experienced in lots of places, accessing things that you might find very easily in rural areas like straw or fencing, right? So these are general challenges. Funding for small items, large and small, from seeds and tools to fencing and generators.

Kristin Reynolds: And then finally, the challenge of perceived legitimacy or illegitimacy, I suppose, in terms of thinking about urban agriculture and whether it is a legitimate or good use of urban space, when we think about this context of highest mass use, the potential to use that space for other things like income generating rents or housing. And then in terms of legitimacy as quote-unquote “real agriculture.” And so this is also a challenge throughout the world. Couple of these images on the right hand, my right hand side anyway of the slide, demonstrate some of the government actions in New York City that have basically kind of enacted or acted on this perceived lack of legitimacy for urban agriculture in the city.

Kristin Reynolds: Giuliani, when he was mayor in the ’90s, sought to sell off many of the city owned gardens. Those were eventually saved by a couple of non-profit organizations. And this came back in about 2015 and ’16, when de Blasio’s administration had also proposed to sell off gardens in order to build housing. So these are examples of general challenges to urban agriculture that we discussed. They can be felt more by some communities and particularly as related to what I’ll be talking about in a little bit. Low income communities, those that are experiencing the brunch of structural racism vis-a-vis policymaking. So I want to then close this section by saying that despite these debates and challenges and drawbacks and critiques, I always like to point out that I think urban agriculture is a positive, a net positive for our cities. And then delving down deeply into how exactly, it can help to advance justice and sustainability is an important part of our work as scholars.

Kristin Reynolds: So coming to action research, and this term gets thrown around a lot and it can mean lots of different things. So to frame what I want to talk about here, I consider, or the way that I use action research is as seeing research as a tool to advance social change. This can be participatory action research that means action research that involves community members and the design, conducting research, analysis, writing up results, et cetera. But it doesn’t have to be participatory. And I think that’s an important part of this work that oftentimes these words get used interchangeably, but as we’ve found in some of our research, sometimes the participatory part isn’t wanted or needed by communities, but the research can be contributing to their work nonetheless.

Kristin Reynolds: So, action research has diverse roots in various thinkers throughout the world. Three, that I’ll highlight. WEB Du Bois, who in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, worked with African American folks in communities near Atlanta to conduct surveys documenting racialized inequality, and disparities in their community. And his work more broadly was among the leaders in establishing the fact that racism is a structural rather than an individual reality in our society… Or problem in our society, I should say. Kurt Lewin in the 1940s worked with workers in industrial factories in the United States to conduct research to improve their practices. And he in fact was the first, as far as I understand it, to use the exact term action research. Paolo Frere was an educator in Brazil who taught folks in Brazil who were not literate how to read, so that they could address some of the political challenges they were facing on their own without being reliant on outside researchers or elites to engage in that work. And so these are some of the key figures that you hear about when we talk about urban… Sorry, not urban agriculture, action research.

Kristin Reynolds: And so then there’s, of course, critique. And I wanna talk about the critical approach. So a critique sometimes of action research is whether is this biased because there’s an objective to use the research for social change, does that mean that it can’t be considered like solid research. And a couple of responses to this are, first, that there’s a debate about this question of objectivity in all of social science that goes back hundreds of years. The fact that it’s action research doesn’t mean that it’s more biased or less biased that has to do with the integrity of the research and also, again, connects, or we can be reminded of the fact that in social science, there’s this debate about whether because we as social scientists are looking at social problems, we can never actually be objective, right?

Kristin Reynolds: So that’s a large debate. I won’t go further with that unless anyone wants to talk about it in the Q and A. But, I think that it’s important then to, for those using action research, as all research, to use sound and rigorous methods, we don’t bias our results. We use standardized data collection processes et cetera, so that we can get the best data that we can to inform the changes, whether it’s about food justice, environment, other social problems the best data that we can. And then the last thing I’ll say on this is that there are also critical approaches, Maria Elena Torre, Michelle Fine and their colleagues at the Public Science Project at the CUNY, City University of New York. Talk about this approach of critical participatory action research which encompasses all of what I’ve just talked about, but also is specifically using feminist standpoint theory, thinking about positionality of researchers, recognizing the positionality of researchers following the lead of community when conducting participatory research. And recognizing the diversity of thinkers that have been tributaries to the broader field of action research. So this is the approach that I tend to follow in my work in seeking to use their action research or research to inform positive change towards racial and economic justice in the food system.

Kristin Reynolds: So now I’ll give three short examples from my work using these approaches. The first is the illustrious Beyond the Kale: Urban Agriculture and Social Justice Activism in New York City, with Nevin Cohen, my colleague, we published this book in 2016. We had four overarching goals for this study and the book itself. First, we wanted to understand what strategies urban agriculture activists and leaders in New York were using to specifically address social justice. That is racial justice, economic justice, gender justice, those kinds of questions through urban agriculture. Beyond the general benefits like improving food access or providing outdoor space for people together.

Kristin Reynolds: We’ve specifically wanted to speak with folks of color and women who were leading this work. And I guess I skipped around, so I’ll just finish that point. The reason that we wanted to do that is we wanted to help to shift the narrative through our work away from this thing that we were seeing. Like I talked about a few minutes ago, this tendency to say, “Oh, look in the media, look at this new urban agriculture activity that’s cropping up.” And all you see is like white hipsters, right? And we knew that wasn’t true. And so we wanted to use the skills that we had and the access that we had to publishing to help shift that narrative.

Kristin Reynolds: Coming back to this point here, we wanted to understand how specifically folks and groups, using urban agriculture, were addressing political and economic inequity in the city. And then coming down to the last point, we wanted to ask, learn, understand if there are possibilities for social scientists like ourselves to use our tools of research and our access to publishing, et cetera, to support this kind of on the ground work. The project built on a project that we were part of prior to the, Beyond the Kale Cloud five Borough Farm, in which we, with a group of additional researchers, sought to understand and document the whole landscape of urban agriculture in New York, propose policy recommendations and metrics and evaluation tools to understand what was happening broadly. In that study, we heard from people that there were racial, economic and gender based disparities throughout the urban agriculture community in New York City.

Kristin Reynolds: And because we weren’t focused on this and we weren’t able to write too much about this in this publication Five Borough Farm, we thought we’re just going to do another study on this so that we can really investigate or dig into to this problematic. So we conducted interviews with farmers and gardeners and non-profit staff. Again, explicitly trying to speak with women, identified folks of color who were leaders in the field. We held a focus group. We held a public forum at the new school where we invited some of the folks that where we were speaking with in the interviews, as well as those working in academic institutions, to have a conversation about whether or how we might collaborate together to work on food and social justice issues or what scholars could do.

Kristin Reynolds: We engaged in participant observation, policymaking and activism, reviewed documents with policy documents. And our approach was a grounded theory approach, and that means that we weren’t trying to test a theory and see if it was true on the ground, but rather listen to people as we ask them and they responded to the questions that we asked, and try to kind of understand some broader trends and themes that we were hearing from people on the ground. This map shows the sites of all of the people that we interviewed. So we made an effort to have representation in all of the boroughs and we were happy that we succeeded in doing that.

Kristin Reynolds: So we heard a few things, so this is… I know you’ve seen this slide before, that’s intentional, I wanted to talk more about what these groups do. So Yonnette Fleming, she also is known as Farmer Yan, leads workshops for women farmers and women in the community that are focused on food justice, but also confronting patriarchy in their lives and confronting racism in the food system. She’s a very adamant and vocal leader in this field, and she also now does a lot of work with youth of color leadership programs in her community. La Finca del Sur, as I mentioned, is a farm that describes itself as being run by women of color and their allies.

Kristin Reynolds: They hold events and hold a safe space on this farm, which is, if I remember correctly, a couple acres in size in the South Bronx, in order to create safe spaces for women, but also to connect with the reality of women farmers in the global South, which are some of the communities of origin for some of the participants in this farm. Noting often that in some places of the world, women-identified farmers make up 50% or more of the farmers, though the representation is often that agriculture is a male activity. Ray Figueroa is at Friends of Brook Park and has since become the president of the New York City Community Garden Coalition, and he runs programs that are both, bringing folks to the farm to engage in policy advocacy that brings together advocacy for gardens and for housing. As you might imagine, oftentimes, I’m sure it’s true in many… I know it’s true in many cities, garden advocacy is pitched against affordable housing, like why should we build a garden when we can build affordable housing.

Kristin Reynolds: Ray has worked with colleagues to have bring those two advocacy communities together and argue for both of those things, both and kind of approach. He also runs an alternative to incarceration program for youth, and we can recognize that the majority of youth in New York City who are involved in the criminal justice system are Latinx and are Black African-American youth. And so there’s this multiple layers of justice that are embedded in the work that Ray Figueroa is leading.

Kristin Reynolds: And then finally, again, Elder Abu Talib, who is one of the leaders at the Taqwa Community Farm in the South Bronx who uses this farm to pass on agricultural traditions to younger generations to make safe spaces, again, for youth in a place where there’s not a lot of other kind of greenery and outdoor space where youth can just gather and be free.

Kristin Reynolds: So these are ways that these particular individuals and organizations that they work with are using urban farm sites to specifically work on racial and economic and gender justice issues that step beyond, again, just the other important part of this, which is growing food. And then I would like you to ask you to think back to what I mentioned in terms of general challenges to urban agriculture, land access, funding. Well, in the interviews with these folks, we heard about those challenges and others that are connected to the reality of unequivocal power and privilege as it plays out in the New York City environment. So the reality of political disenfranchisement in low-income communities, not having the easy access to city council members, for example, to try to advocate for a change in a local law to support a particular agricultural activity, and having limited financial resources in the community. Stories like needing a few hundred dollars to buy a generator, and then the individuals in the community don’t just have that in their pockets, whereas in a more wealthy community, that might be the case.

Kristin Reynolds: Stereotypes like, and I’m reporting on what we heard in our research, stereotypes like farmers that might come and sell at a farmer’s market in a low-income community thinking, “No, folks in that community don’t like fruits and vegetables, or thinking, “It’s too violent and dangerous, so I won’t sell my products there, I won’t go there.” To be clear, these kinds of stereotypes are really what some of the groups are even responding to, right? They can’t get farmers from the rural settings, or they couldn’t, to come and sell at their markets, so they’ve then grown their own. A challenge of not being trendy. I’ll talk in a few minutes about commercial urban agriculture, rooftop farming, these things that you see that are like the new face, the non-human face of up-and-coming urban agriculture. And so what we heard from folks is that funders were like, really excited about rooftop farms, or they’re really excited about, these controlled environment agriculture spaces, and people just doing kind of boring old farming in the ground weren’t trendy enough, or weren’t exciting enough for funders to be giving them money. Of course, this was not across the board, but it was a challenge confronted and expressed by some of the folks that we spoke with.

Kristin Reynolds: So a lot of these, you see this quote, I’m sure by now you’ve read this quote on the slide by food justice leader Karen Washington, who kind of sums up some of this power and privilege, unevenness as she has seen it play out in her community with respect to urban agriculture and the food system more broadly. But I wanted to close this slide by just mentioning that there also was mentioned that there was less support funding for quote-unquote “radical work”, and specifically, farmers and gardeners spoke about wanting to do, and they were doing, anti-racist work, anti-racism work on their farms and gardens with youth, with adults. But that funders didn’t wanna to hear about that. They had to learn how to use, like, more placating language. They couldn’t talk about this. Now, I think that some of this has shifted following the murder of George Floyd in 2020. Remember that this research was conducted almost 10 years ago now. But I would suspect that some of this remains true. And so these are challenges that have been experienced more specifically than the broader challenges of land access, and the broad challenge of needing funding.

Kristin Reynolds: And so as a final point from this book, before I move on to another couple of quick examples. We specifically asked questions, as I mentioned, about what roles researchers might play. Oftentimes, this comes about in the end of a book or the end of a publication, and those writing just kind of think about it and write what they think would be good, which is great. And we can also ask folks on the ground. So we asked that question, in a few different ways. Here are some of the things that we heard, that we researchers from the outside can highlight and legitimize urban agriculture and social justice activism. That’s what we tried to do in this book. And right now I am recording on it.

Kristin Reynolds: But that rather than focusing on documenting constantly, like the types of urban agriculture that exist out there, what about like lifting up this critical and important work that’s being done that is often not highlighted in media. Again, yes, a little bit more now, I think, but the point still stands. Contextualizing urban food concerns in terms of, it’s not just about whether there’s a supermarket there, but it’s about inequitable food access is about, it’s about racialized poverty, it’s about multi generational unemployment, right? And that this is a role that scholars can play when we can write pieces and conduct analyses that really contextualize what’s going on in the broader social and economic structure.

Kristin Reynolds: And then finally, this part is about approaches and that we heard folks tell us we don’t really need you to ask more questions about what we’re doing. And I don’t mean interview questions, but broad research questions, but rather like take a different approach, engage with us in community driven research, work with us on participatory action research, in some cases, not everybody said this. And I think this is really revelatory. And in the research world, you’re always thinking about what’s the newest research question. And that continues to be true. But then also stepping back to think about how we enact the social justice practices that we write about theoretically, in the work that we do as researchers and scholars.

Kristin Reynolds: So that’s a quick overview of that book, I’ll talk about briefly about two more current projects. And the first is about some evolutions in commercial urban agriculture and policy. So I’m speaking from a couple of research briefs that I’ve written in the past few years that pertain more specifically to New York City, and Paris, I did some work with a colleague, Siquel Andali and then I will talk… I’m also talking about some ongoing work with a PhD student here at The New School. So commercial urban agriculture, I call it like 1.0 people growing food in the city and selling it. So Andrew Coté is a well-known beekeeper in New York City who sells at the green markets all over the place, you can look him up, he’s a social media star.

Kristin Reynolds: And Brooklyn Green was the first large outdoor rooftop farm, commercial, and they have a nonprofit arm. And Gotham Greens is a rooftop greenhouse, they have rooftop greenhouses in New York and other cities like Chicago. And this is a picture of their greenhouse in Brooklyn on the top of a Whole Foods Market. So this is what I call commercial urban agriculture, 1.0 And then there’s ag tech. Now this doesn’t just pertain ag tech of the term is not only about urban agriculture, but of course, that’s what I’m focused on here today. And there’s… I don’t have time to get into a complete disambiguation of terms here. But ag tech broadly is the use the use of technology and agriculture, of course. We can debate about what you consider, well we consider technology.

Kristin Reynolds: But when I’m speaking about urban ag-tech, it’s… Examples like you see here on the slide, vertical farming, which may be small scale or large, in warehouses, like you see in this photo, controlled Environment agriculture, well, they’re all controlled environment agriculture, actually, meaning they’re not outside, they’re controlled in terms of humidity, temperature and whatnot. So this is a photo of the company Square Roots that grows in shipping containers. Oftentimes, a lot of these types of production practices are using grow lights. So like the pink has been this kind of, it’s the color du jour.

Kristin Reynolds: And growing mushrooms, like Smallhold does in, again, controlled environments, this one is controlled remotely and can even be controlled at a distance and other in restaurants and homes. And at my last count, there were at least 25 such sites in New York City proper, and maybe slightly higher by now. But this is what I’m talking about when I’m talking about like ag tech and commercial urban agriculture. And we’ve also seen recently policy changes at multiple levels of government.

Kristin Reynolds: Look, making it easier for urban agriculture… Or communities to be zoned for urban agriculture, comprehensive plans that are addressing urban ag, there’s one in the works in New York City, policy papers and proposed legislation such as this one, which was put out in 2020 by now Mayor, Eric Adams, but he was then Borough President and mayor or candidate, claiming that urban agriculture could be part of kickstarting again, New York’s economy, you can see the reference to the pink lights here. And at the state level, California was a leader in 2013, creating what it called agriculture incentive zones that gave incentives for private landowners to make their land and cities available for commercial agriculture, urban agriculture use.

Kristin Reynolds: And I forgot to mention that, though I don’t know a lot about it, but maybe we talk about it later, but I know that there has also been a recent legislation in Boston, back to the municipal level to also support commercial urban farming. At the federal level, United States Department of Agriculture agencies began to pay attention to urban agriculture as the commercial and rooftop farming scene was ramping up. So they included them in their annual outlook for, started creating programs. This was the agricultural marketing service and the farm service agency, which grants loans to farmers. And then the US Farm Bill of 2018 created what is called the Office of Urban Agriculture and Innovative Production. Through that, provision in the farm Bill, excuse me, this office and a director position was created.

Kristin Reynolds: A granting program was created to support this type of activity, as well as a federal and local county offices and committees to advise, Secretary of Agriculture on supporting urban agriculture and innovative production. So these are all positive steps for urban agriculture writ large. But there are some narrative shifts that are also taking place that we need to pay attention to, including a tendency, and here I’m also referring to some work by colleagues, Goodman and Miner in 2019, as well as Fair Brown been fair, and Julie Guzman and colleagues who have had a large project looking at this tech sector. So solutionism a narrative that urban agriculture, ag tech in particular, is going to help solve food insecurity under climate change, contribute to urban sustainability. This is being pitched in both business and government sectors, as you can see represented by these images on the slide.

Kristin Reynolds: But we have to question this and in first in terms of the types of products that urban agriculture tends to produce. It’s not staple crops like grains and tubers, but rather salad greens. But also in terms of the solutionism is create… Pitching urban agriculture as the silver bullet without necessarily compelling us to look beyond why we have food insecurity and why we’re seeing increasing environmental degradation and climate change.

Kristin Reynolds: And then the second part of this is the pitch of profitability. You look online, you’ll see lots and lots of this narrative, that urban ag tech is going to be a great investment for venture capitalists. There are mixed results in the latest report from the ag tech firm, AgFunder that does an annual census of controlled environment agriculture. But nonetheless, this pitch is often the triple win, planet, food security, environmental sustainability, and profitability. But then when we see all of this happening, we have to take pause, I think, and think about the effects that the legitimization of commercial urban agriculture in particularly high tech urban ag, might have on the structure of the field, or it might be called a sector in this case. What does it mean for community based and grassroots organizations that are trying to grow food for their communities and do some of the things that I talked about, in the Beyond the Kale book. And then second, what effects might this have on racial or economic equity in the food system? So this is something that I’m addressing in a paper I’m writing with my, one of my graduate students, Edric Godfrey, here at the New School. So I know I’m out of time, but I just wanna close by talking about a new initiative that I’m starting called, The Food and Social Justice Action Research Lab at The New School.

Kristin Reynolds: I have another graduate student, Constance Smith, who is helping me with this. Our vision is to contribute to racial and economic justice through action research, to collaborate with community-based organizations and institutions including BIPOK, and people of a global majority led groups, and to build relationships with community members and others consumed with food and social justice to collaborate together in ways that seem fit. So this is being… I’m kinda building this out within our food studies program. Information is at this website that you see on the slide. So we, in 2022 and ’23 last year, had conversations with community leaders to ask them what might we be able to do through research to support your work? We wanted to understand what are some similar initiatives that exist in New York at The New School so that we can build upon and contribute to this community, and not be duplicative.

Kristin Reynolds: And then we were exploring new collaborations so that our first project, and I know that Dr. Kara A. Woods was on the call at one point. I don’t know if she’s still here or not, but if you’re, hello. Our inaugural project is looking at the social equity implications of this new office of urban agriculture through a racial equity lens. And so this is a project that’s in process, so I won’t report on any findings at this point, but what we’re seeking to understand is the implications when we think about the discriminatory practices of on part of the USDA toward farmers of color throughout many decades, history, and what we’re seeing in terms of racial equity with the rollout of these farm bill mandate, these farm bill created programs. The work is supported by the socially disadvantaged farmers and policy research center at Alcorn State University. And so we’re happy to be in collaboration with those folks and with Dr. Woods.

Kristin Reynolds: And so to conclude, I just wanna try to bring this all together. That we need to recognize, first of all, the significance of urban agriculture’s multiple benefits. And this is something that’s really often spoken about in urban agriculture work. But going beyond that, we also have to think about the structural dynamics of urban agriculture. When we think that, or we want to say that urban agriculture produces social benefits or social justice benefits, we need to really examine those claims in the context of a given initiative or project. What do narrative capture mean for racial justice? What does it mean to just say urban agriculture, a garden’s there, an urban farm is there, now we’ll have food security. And so I think that throughout all of this, I hope what I’ve communicated is that… Or no matter the format of urban agriculture, we need to be asking like deeper questions about social and economic inequality and inequity.

Kristin Reynolds: And then finally, I think that there are real roles that action researchers can play in supporting this work on the ground. I think we’re in the turning point with urban agriculture in US policy. It’s not to be overly optimistic, but there’s certainly much more attention in actual policy action taking place. And so it’s a call, I suppose to get an invitation to those of you who are here who are engaged in research or want to be engaged in research or studying to think through how that work might be able to best contribute to this broader picture of advancing racial and economic equity in the food system. So with that, I will thank you very much, and I’m happy to take your questions.

Julian Agyeman: Well, thank you so much, Kristin. What a great survey and expansive look across this vibrant field, which, as we know, is changing all the time. Several questions. First one from Ivy in Chicago. Ivy says, “In Chicago’s Southside, community gardens are seen as a tool of gentrification. What can we do to support these lands staying in neighbor’s hands and not being converted to development?”

Kristin Reynolds: Yeah, that’s a great… Obviously, a great question and always a conundrum in cities where housing is expensive. I live in New York. We have a big affordable housing crisis here. I think that… Maybe I’ll say two things, because I don’t know what your involvement is, the person that asked the question in urban agriculture. If one is thinking that, “Oh, there’s an empty lot, there should be a garden there.” Talk with the community. Does the community want that? Or if you’re part of the community, still, talk with the rest of your community. Because I think a lot of times, the questions about gentrification are certainly first and foremost about affordability in housing. But it’s also about a community self-determination. And so in what ways are those of us who are interested in urban agriculture as an activity engaging with that problematic? And I have this question all the time, and sometimes the answer is like maybe a garden shouldn’t go there.

Kristin Reynolds: But I think the other broad question is, or point is to get involved in policy advocacy. You have the ward system in Chicago. Speak with your local, your representatives, find out what’s happening in terms of city zoning, and make those connections as I was speaking about one of the actor, the people in here in New York, make those connections between advocacy for housing justice and housing affordability and advocacy for community gardens and food access because they’re often pitted against each other. But I think that what I’ve seen here in New York is that when strategic alliances can be built, that can help address this equity from a broader lens than being about one versus the other. But I think, gentrification is such a conundrum because of the affordability crisis, so, couple thoughts.

Julian Agyeman: Right, thanks, Kristin. Bobby Jones, a long question, but I’m gonna cut to a really important point. “Speaking more broadly, what are some of the tangible ways commercial urban ag folks can show solidarity with the more traditional diverse urban ag that’s not focused on commercial production?”

Kristin Reynolds: Well, I think a lot of times my answer begins with talk with the communities, because I don’t know the answer for all communities, of course. But beyond that response and a lot of times, okay, so if there’s narrative capture or capture of policy makers attention happening, can those that are engaged in this high tech commercial urban ag say, Well, yes, we are part of urban agriculture. And there’s this other part of urban agriculture and we want those folks to be in policy making decisions and conversations as well. So, passing the mic, I guess, is what I’m saying, or making the mic more inclusive. And maybe, if this comes back to asking the groups, but a lot of times community [0:50:24.9] ____ groups are also in need of funds of some sort. So when we’re seeing, $100 million dollars put into a venture, can some of that be used, re-granted or be given I suppose to organizations if they need it. But again, I come back to you ask them.

Julian Agyeman: Good. Thank you. Joel Robinson, who’s, I think, an architect, because he, she, they, say, “Do you think it’s possible for a role for architects, designers, etcetera, in socially responsible growth sharing urban agriculture, or does that always end up being somebody’s vanity project, taking control away from the grassroots organizers? Elite capture, is that happening?”

Kristin Reynolds: Yeah, I think so. I think I might have missed the key word in the question about sharing or, but…

Julian Agyeman: Yeah, I think the the question is about architects, designers. Is there a role for them in socially responsible and pro-sharing urban agriculture?

Kristin Reynolds: Yeah, I mean, I’m sorry to keep saying the same thing, but I think it has to do with asking the community and I work at The New School, and we have a large design school here. So I can time to time interact with design students or design labs that are… Of course, everybody’s interested in urban agriculture ’cause it’s exciting and it’s fun. And I think that what I’ve seen is that sometimes the design field doesn’t take that approach. I know there’s the whole field of user-centered design. So I think that’s part of it. But then… Again, what does the community want? And I mentioned a few minutes ago that I often get questions like this just even having conversations with people in my daily life about how to best help build gardens. And another answer I often give is to be clear in what you want to do in terms of the help. Do you wanna help the community? Do you wanna build a garden? And sometimes those answers don’t go together. And if you wanna build a garden, that’s great, and find where that makes most sense in terms of the community desires. If you really wanna help the community, kind of the same answer from a different angle. What does the community need and want and how can you use your skills as an architect to help support that.

Julian Agyeman: Thanks Kristin. We have a question from Patrizia La Trecchia, University of South Florida. Thank you for a great talk. You were mentioning the narrative that agriculture is a male activity. Patrizia is interested in women’s presence in emerging farming, or emerging in farming communities in Southern Italy, where historically women have been denied land owning because of inheritance laws and rules. And she says, “Today’s communities of young farmers are appropriating rural traditions from remote areas revealing an increasing feminization of agriculture. Is there a feminization of agriculture in the US as well?”

Kristin Reynolds: Well, I’m not that familiar with the Italian agricultural context. I do know a bit about France where I spend a lot of time, in terms of the United States. So here’s a question that also connects back to statistics. The USDA, if for those who aren’t familiar is our main agency that collects agricultural statistics in the United States. And there’s this five year, every five years census of agriculture where they collect those types of statistics. What has changed over time with the USDA census of agriculture is that they’ve changed the categories. And I won’t get too much into the weeds here about this, but they’ve changed the categories such that more female identified farmers are showing up in the agricultural census. And so we see that in terms of statistics that’s true. In terms of, has there been an actual shift on the ground? What do I wanna say about this, it’s not really my area of research right now, but I did work on this many years ago when I worked in California that I think that there’s the recognition piece of it. And you started, I think this question started out in terms of the narrative.

Kristin Reynolds: But then there’s also the different, like small scale and community spaces that are flourishing now that allow more collaborative work with… Among farmers who might not have found community. And so to specifically speak to this question of gender, again, I’m stepping a little out of the area of what I work on, but I know a little bit about it. When I used to work on this topic, when I lived in California, I had worked in extension, I heard from people talking about how the… Like purchasing supplies was male dominated, the salespeople wouldn’t even speak with women farmers. Like all the equipment was suited for large bodies. And I think that over time the building out of a community of women, but also I wanna bring into this quest, into this topic. LGBTQ identified farmers has indeed, I think made more openings for farmers who are not men. Not only to farm, but also to have a farming community that supports them in their work.

Julian Agyeman: Thanks. I think we’ve got probably time for one last question. And that goes to Rahul. “Are there any examples of non-commercial urban gardening ventures that have successfully gotten the attention of commercial funds, policy makers, philanthropists in any way? And what did they do? How do you manage the non-commercial and commercial pressures?”

Kristin Reynolds: My first answer is, I’m not totally sure, but what I wanna say next is.

Julian Agyeman: Absolutely.

Kristin Reynolds: Because I mean, the reason I paused is because when I… Funding for non-commercial gardens and farms is foundation grants, public monies and individual donations, funding for commercial high-tech urban ag, like I’ve been talking about is at least coming from the private sector. And a lot of times it’s coming from venture capital. And so those funding streams don’t necessarily meet. That’s why I kind of paused. But the example I wanna give is in fact about… I mentioned Karen Washington. She’s a major food justice leader and community gardener here in New York City, who, with three colleagues several years ago was able to begin farming outside of the city, in a place called Chester in New York. It’s called Rise & Root Farm. I was just there last weekend for one of their annual harvest events.

Kristin Reynolds: And so it’s a group of women identified, two Black farmers, three LGBTQ farmers who have started this community farm building on the work that they have done in the city, and certainly being able to have access to financial support through the networks that Karen Washington and her colleagues had built and to start this farm, which is both addressing these like representational and equity to land access questions, but also directing the food that they grow to lower income communities. So I know it’s not exactly an answer to that question, but for me it is an example of community gardens and garden leaders focused on justice issues, being able to leverage some of the social capital, I suppose that they have to start farming outside of the city in a more commercial but certainly community oriented sense.

Julian Agyeman: Well, Kristin, thanks so much for sharing your knowledge, your expertise, and your answers to questions are fantastic. Let’s give Cities@Tufts thank you to Kristin.

Kristin Reynolds: Thank you very much for having me.

Julian Agyeman: Thank you. And our next colloquium is on October 25th, and it’ll feature Maya Singhal, who’s a PhD student talking about her doctoral research, How to Fight a Mega-Jail. Fascinating. Thank you. And see you in a couple of weeks time. Thank you. Bye-bye.

Tom Llwewllyn: We hope you enjoyed this week’s presentation. Our next lecture, How to Fight a Mega-Jail with Maya Singhal will take place on Wednesday, October 25th. Click the link in the show notes to register for a free ticket. Cities@Tufts is produced by Tufts University and Shareable with support from the Barr and Shift Foundations. Lectures are moderated by Professor Julian Agyeman and organized in partnership with research assistants, Deandra Boyle and Mariam Bakari. Light Without Dark by Cultivate Beats is our theme song, Robert Raymond is our co-producer and audio editor. Additional communications, operations and funding support are provided by Paige Kelly, Allison Hoff, and Bobby Jones. And this series is co-produced and presented by me, Tom Llewellyn. Please hit subscribe, leave a rating or review wherever you get your podcasts and share with others so this knowledge can reach people outside of our collective bubbles. That’s it for this week’s show. We hope to see you next.