“Infrastructure Apartheid to Liberatory Infrastructures” – this phrase highlights a fundamental shift in our framing of both harms and solutions, respectively, from individual and direct, to systemic and distributed. Dr. Carrasquillo and the Liberatory Infrastructures Labs’ aim, as they continue to not only challenge the theoretical framings but also engineering approaches, is to research and pilot fieldwork that ultimately brings us closer to an envisioned future where liberation can be realized. This edition of Cities@Tufts highlights both theory and current research from the lab that demonstrate how they are examining, critiquing, and working towards this goal.

About the Presenter

Maya Elizabeth Carrasquillo (she/her/hers) is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering and is the Principal Investigator of the Liberatory Infrastructures Lab (LiL) at the University of California, Berkeley. The mission of LiL is to develop systems of critical infrastructure that support liberation and restorative justice for all, particularly of historically under-resourced and historically marginalized communities. LiL is committed to evaluating, designing, and implementing just and liberatory critical infrastructure for current and future generations.

Dr. Carrasquillo holds a B.S. in Environmental Engineering, a minor in History from the Georgia Institute of Technology, and a Ph.D. in Environmental Engineering from the University of South Florida. She is a Huelskamp Faculty Fellow which recognizes a promising new assistant professor in UC Berkeley’s College of Engineering for their innovative research. She is also the Inaugural Faculty Director of UC Berkeley’s new initiative for Community Engaged Education in Civil and Environmental Engineering (CEE2). Dr. Carrasquillo is a certified Envision Sustainability Professional (ENV SP) and EcoDistricts Accredited Professional.

About the series

Shareable is partnering with Tufts University on this special series hosted by professor Julian Agyeman (Co-chair of Shareable’s Board) and Cities@Tufts. Initially designed for Tufts students, faculty, and alumni, the colloquium has been opened up to the public with the support of Shareable, and The Kresge Foundation.

Cities@Tufts Lectures explores the impact of urban planning on our communities and the opportunities to design for greater equity and justice.

Register to participate in future Cities@Tufts events here.

Listen to the Cities@Tufts Podcast (or on the app of your choice):

Infrastructure Apartheid to Liberatory Infrastructures Transcript

[music]

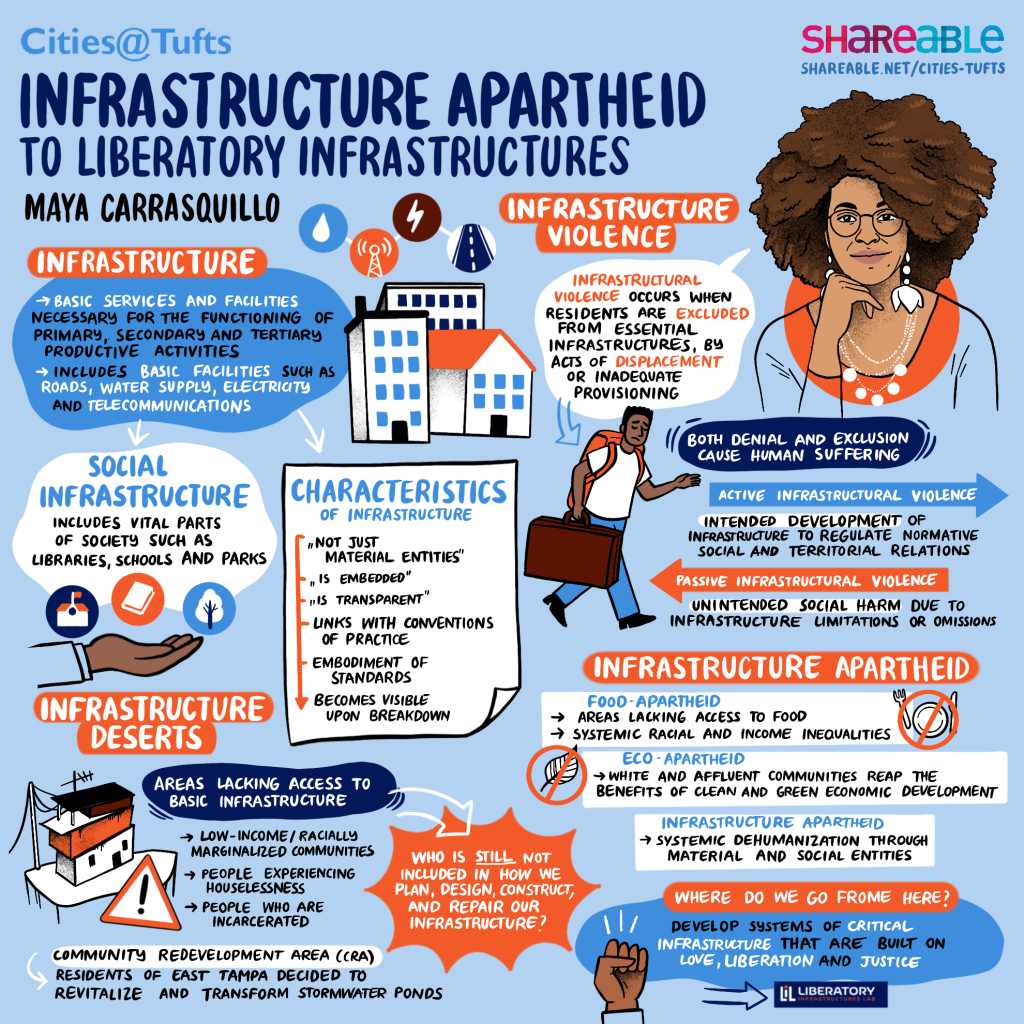

0:00:06.4 Dr. Maya Carrasquillo: Thinking about infrastructure apartheid as systemic dehumanization through material and social entities that are observed, felt, and lived across racial, economic, and geographic spatialization. Thinking about infrastructure as it is established, it is therefore embedded through existing and interlocking systems of domination, oppression, and dehumanization. Challenging this notion of infrastructure being transparent to those who are most affected by its presence, whether positively or negatively, it is seldom, if ever, transparent. Its links with conventions of practice is the very thing that reproduces harm, violence, and warfare when embodying these standards that were built by and for the dominant majority through historical legacies of colonialism, imperialism, racism, sexism, all of the isms can go on and on and on. And this idea becomes visible upon breakdown.

0:00:54.2 Tom Llewellyn: Welcome back to another episode of Cities@Tufts, brought to you by Shareable and the Department of Urban and Environmental Policy and Planning at Tufts University with support from the Barr and Schiff Foundations. Today’s show features a lecture from Dr. Maya Carrasquillo, who discusses infrastructure apartheid to liberatory infrastructures. In addition to this podcast, the video, transcript, and graphic recordings are available on our website. Just click the link in the show notes. And now, here’s the host of Cities@Tufts, Professor Julian Agyeman.

[music]

0:01:40.2 Julian Agyeman: Welcome to our Cities@Tufts virtual colloquium. I’m Professor Julian Agyeman, and together with my research assistants, Deandra Boyle and Mariam Bakari, and our partners Shareable and the Barr Foundation, we organize Cities@Tufts as a cross-disciplinary academic initiative, which recognizes Tufts University as a leader in urban studies, urban planning, and sustainability issues. I’d like to acknowledge, and we would all like to acknowledge that Tufts University’s Medford campus is located on Colonized Wampanoag and Massachusetts traditional territory. We are delighted to host today Dr. Maya Carrasquillo, Assistant Professor in the Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering and Principal Investigator of the Liberatory Infrastructures Lab, or LIL, at the University of California, Berkeley. LIL’s mission is to develop systems of critical infrastructure that support liberation and restorative justice for all, particularly of historically under-resourced and historically marginalized communities.

0:02:42.7 Julian Agyeman: LIL is committed to evaluating, designing, and implementing just and liberatory critical infrastructure for current and future generations. Dr. Carrasquillo holds a BS in Environmental Engineering and a minor in History from Georgia Institute of Technology, and a PhD in Environmental Engineering from the University of South Florida. Her research has primarily studied the intersections of stormwater management, environmental justice, and complex hydro-social systems. I like that complex idea, hydro-social. Particularly focusing on historically underserved communities to develop a conceptual framework for equitable decision making. Maya, a Zoom-tastic welcome to Cities@Tufts. Over to you.

0:03:29.3 Dr. Maya Carrasquillo: Good, I guess, afternoon for everyone joining on the East Coast. I’m West Coast time, so it’s still morning for me. I’m so excited to be here. And I have a lot of slides to get through, so I’m going to share screen and jump right in. But yeah, really looking forward to being here to present today, and yeah, sharing this space with you all. Just a second. All right, are you seeing my slides okay? Hearing no objections, I’m going to assume that everyone can see. Well, yes, thank you again for that introduction, Julian. Again, really excited to be here, and thank you for the invitation to present this evolving work and framework for my research and my group’s, my lab’s research. So yeah, the title, Infrastructure Apartheid to Liberatory Infrastructures. All right, so title, Liberatory Infrastructures, Infrastructure Apartheid. I’m gonna walk through kind of three main buckets for the presentation today. I wanna give you a little bit of introduction to me, my orientation for this work. As I mentioned, this is an evolving and a constant area of thinking of scholarship for me and my lab.

0:04:45.8 Dr. Maya Carrasquillo: And so I want to kind of walk you through that intellectual journey a bit today and share that evolution of where the work started. And as we start to think more about what does liberatory infrastructures, what can it look like, what does it look like, how are we thinking about it, sharing a bit about some of the work that my lab group is doing today. So motivation… I like to start with the scripture that really hits on this idea of what it looks like to actually care for our brothers and sisters. So it says, “For I was hungry and you gave me something to eat. I was thirsty and you gave me something to drink. I was a stranger and you invited me in. I needed clothes and you clothed me. I was sick and you looked after me. I was in prison and you came to visit me. Truly, I tell you, whatever you did, for one of the least of these brothers and sisters of mine, you also did for me.” So this is one of the scriptures that really grounds a lot of the work. And even as we start to think about what does liberation mean and caring for others and kind of challenging ideas of dehumanization that I’ll get into a little bit more.

0:05:49.6 Dr. Maya Carrasquillo: Yeah, this really kind of grounds a lot of my thinking in this work. So you heard the bio. I’ll jump through the slide pretty quickly, but a little bit about me. As Julian mentioned, I graduated, did my BS in environmental engineering at Georgia Tech. Originally from upstate New York. So I am very familiar with part of the country that you all are in. And I apologize right now for I’m assuming what is probably pretty frigid weather in Boston. I am the youngest of three siblings. This is a picture of my mom and my sister. We actually all graduated at the same time when I finished my bachelor’s. As I mentioned, did my bachelor’s at Georgia Tech and was involved very actively with organizations like the National Society of Black Engineers, our African-American Student Union. And it was in these spaces that I really began to think about kind of challenging what I saw as normative practice in engineering.

0:06:42.7 Dr. Maya Carrasquillo: My background as an environmental engineer and kind of sitting in this interesting space as engineering undergrad, but also in what is probably now to date the largest and still predominantly Black city in the US and seeing maybe the disconnect between this very prominent PWI in the middle of Atlanta and the infrastructure that as a campus we were building that was harming our neighbors next door. And so really began thinking about what does it look like to actually integrate community engaged practices in engineering more concretely. So I went to do my PhD in environmental engineering at the University of South Florida. From my PhD, I jumped into consulting. I did a brief stint in consulting before joining faculty here in civil and environmental engineering at Berkeley. In my spare time, whatever that actually looks like, I also lead outreach for my local church and also sermon worship as well. And as I believe, Deandra, I am getting married in less than two months. So very exciting and busy, but full season for me.

0:07:51.0 Dr. Maya Carrasquillo: A little more context. So I come from a family of activists and educators. And I like to highlight this because I think, again, as you understand my position and how I approach this work and even what motivates it, highlighting my family’s history and particularly the women in my family and the legacy of activism and scholarship and that tradition that they hold, I really believe is a huge part of why I am and have always gravitated towards this work myself. So from left to right in this picture is my great aunt Jackie, my great great, great grandmother Ola, my great, great, great grandmother Nori, my great grandmother Elizabeth, and my late grandmother Elizabeth as well. In particular, I like to highlight some of the work of my great grandmother Elizabeth, who I bear her name through my middle name and will also be taking her last name as well. But my great grandmother in particular was an activist and educator in Harlem, was actively involved with March of Dimes, held leadership positions with Washington Heights, the Democratic Club.

0:09:06.2 Dr. Maya Carrasquillo: And so, again, coming from this tradition of activism and education and community involvement has very much so driven so much of the work that I do. And it is because of the women who have preceded me in my own life that I am where I am today. So let’s dig into the work. How it started. So before we jump in, again, I’m an engineer. I know that the term infrastructure is very loaded. And when we say it, people may have different understandings of what that means. So I want to level set a bit before we jump into the rest of the conversation to make sure that when I say infrastructure, we’re operating from the same understanding. And again, because I come from the tradition of engineering, a lot of definitions will often focus on basic services. This definition highlights primary, secondary, and tertiary productive activities. We can debate what productive actually means, but in terms of functionality in a society. So in its wider sense, it embraces all public services from law and order through education and public health to transportation, communications, and water supply.

0:10:13.0 Dr. Maya Carrasquillo: Infrastructure can include all essential systems and facilities that allow the smooth flow of an economy’s day-to-day activities and enhance people’s standard of living. It includes basic facilities, excuse me, such as roads, water, supply, electricity, telecommunications. So most definitions that you’ll see of infrastructure, again, coming from my tradition, civil and environmental engineering, often refers to built and material infrastructure systems. What’s often excluded from even our orientation as a field when we think about infrastructure is social infrastructure. In the classes I teach, I like to ground it with this perspective. And so we think about social infrastructure, it’s built, but also the non-built, non-material spaces that can include libraries, schools, playgrounds, parks, athletic fields, and swimming pools. Things that are vital parts of social infrastructure, but really vital parts of society and the ability for us to gather and operate from person to person.

0:11:18.4 Dr. Maya Carrasquillo: So within our field and our tradition, there are accepted characteristics of infrastructure. I’m going through this slide because it’s going to come back up later, but some key points to highlight on this slide is that infrastructure, as kind of just spoke about, it can include social, so it’s not just material entities. It’s embedded, so it exists within established networks and relationships. It’s often understood to be transparent, which again is an idea that we’re going to come back to later. So this idea that when it’s being used, it’s often not noticed or we don’t think about it. So here in the US, I’m sure everybody already today has turned on tap water. We’re very privileged to have that opportunity, but you do it so subconsciously at this point. It’s a daily part of your routine. You don’t actively think about it. It’s there. We use it on a regular basis. Toilets can be included. I’m jumping to all the water infrastructure ’cause I am a water engineer by training, but you get the idea that these are systems that we use but don’t actively think about.

0:12:19.8 Dr. Maya Carrasquillo: Links with conventions of practice, embodiment of standards. Again, we’re gonna come back to all of these later. The last one is that it becomes visible upon breakdown. So again, this idea that a lot of infrastructural work happens in the background and it’s not until it’s necessarily broken or no longer functioning as intended that it’s noticeable. So again, these are accepted characteristics of infrastructure. Now in my research, we kind of characterize critical infrastructure. I have a different working definition of critical infrastructure than the Department of Homeland Security, but on this slide highlights six categories or six sectors of critical infrastructure as defined by Department of Homeland Security, particularly as it relates to matters of national security. Within this, we’re not gonna spend too much time on this slide, but we can understand that defining an infrastructure is a political act that focuses attention on certain aspects of infrastructure while ignoring others. So this kind of jumps into the evolution of my thinking.

0:13:19.5 Dr. Maya Carrasquillo: Again, I am situated in engineering and so much of what we talk about when we think about infrastructure is in built material systems. I’m gonna spend the next few minutes talking about the evolution of my own thinking in my scholarship and how it’s shifted from traditions of civil environments engineering to thinking about infrastructure and critical infrastructure broadly, and this distinction between infrastructure deserts and what’s the title of the talk was called, Infrastructure Apartheid. So this is a picture of what was formerly the largest encampment in northern California called Wood Street Commons. So situated just outside of Interstate 80 in Oakland, in West Oakland in particular, Wood Street Commons housed, I believe, around 450 or so houseless individuals for several years. So it was not only just the largest encampment in northern California, but also the longest standing.

0:14:25.2 Dr. Maya Carrasquillo: Living in the Bay Area and moving to the Bay Area, I think what became so striking to me was the extent of houselessness and really began thinking about infrastructure as it related to persons experiencing houselessness. And that kind of sparked a lot of the thinking originally around what was, what I was calling infrastructure deserts. This idea that our infrastructure, particularly in the US, is built on grid systems, whether that’s water, whether that’s energy, what we consider to be some of these critical infrastructures that people depend on for their day-to-day lives are so grid dependent. And so the question began to emerge that if you are not connected traditionally to one of these grids, how do you access food, water, energy? Again, what we consider to be basic needs infrastructure. Began thinking about this in the context of these contemporary policies where we are with the current administration.

0:15:28.4 Dr. Maya Carrasquillo: So between Justice40, the bipartisan infrastructure law, and so much of what we’ve seen actually emerged federally around thinking more critically about environmental justice and particularly addressing and providing services for those or funding for those who are considered to be the 40% most marginalized, underserved, disadvantaged, all the language that the White House and this administration has used across federal agencies. But again, as I began thinking more and more about this challenge, this very real challenge of houselessness in the Bay Area, just how widespread it is, still began thinking about even some of the policies, the language that were being used. And with these new policies and funding, although still focusing on justice more explicitly, there’s still a question of who is still not included and how we plan, design, construct and repair our infrastructure systems.

0:16:26.6 Dr. Maya Carrasquillo: Again, getting back to this idea that our infrastructure is so grid dependent. And so as a result, there are people, if you’re disconnected from the grid, you’re disconnected from these services. And so then how do you get it? So this kind of began the thinking around infrastructure deserts. The date only found one actual working definition. This is out of a team funded NSF project out of Texas Southern University. But so they define infrastructure deserts as low income neighborhoods with highly deficient infrastructure, including street tree canopy, sidewalk, food access, medical service access, and our most prevalent deficient infrastructure types across the city. So again, this comes out of a project based out of Texas Southern and really began thinking about what does this definition include? What does this definition not include? And I was thinking about in the Bay Area, kind of shifted it a little bit.

0:17:26.2 Dr. Maya Carrasquillo: So not just focusing on low income neighborhoods, but infrastructure deserts are more broadly places within these infrastructure grids, as we’ve talked about, where segments of the population are either limited in access or completely disconnected from basic infrastructure, such as food, energy, water, and housing. And this can extend beyond these, but again, thinking critical needs infrastructure. So again, original thinking and how our group was beginning to think about this was kind of bucketed into these three categories. So what is very, very common in this space of EJ social justice work, even in engineering tradition, low income and racially marginalized communities. I mentioned what motivated much of this thinking was the question of infrastructure and service provision for people experiencing houselessness. And then really began thinking about this more broadly, again, if connected to the grid. So if you’re someone experiencing houselessness, but then also the question of what if you’re incarcerated, what does that look like? And this can also extend to communities that may be in unincorporated areas of a city or in the county. So they don’t have direct access to city services, but their services come from the county. And so even that creates a disparity.

0:18:43.0 Dr. Maya Carrasquillo: So again, recognizing that even within spaces that are already hyper-connected, there’s still significant segments of the population that don’t have access to these basic needs. And so starting with the first one, and this is again where much of my previous and original research kind of started thinking about this from the context of lower income, and racially marginalized communities. So I wanna bring us to East Tampa, Florida. I did my PhD at the University of South Florida, and much of my previous research focused and worked alongside residents in this community, East Tampa for a few characterization information is a community [0:19:27.5] ____ area, so under Florida Sunshine Law is an area that is explicitly listed as a blighted community in need of economic redevelopment, and so East Tampa in 2004 became designated as a community redevelopment area or CRA. Still remains the largest CRA in the State of Florida. Not unlike a lot of communities that experience environmental injustice, it’s located between two major highways that cut between Tampa, so I-275, that goes north and south on its western border, and I-4, which is the main highway that’ll take you to Orlando from Tampa along that southern border.

0:20:12.4 Dr. Maya Carrasquillo: And so, as you can imagine, East Tampa is situated within these two highways, has experienced historical challenges around environmental injustice from air quality, transportation and traffic, things of that nature. One of the things that after spending many, many years working with residents in the community, the thing that kept coming up, particularly around stormwater was, why is it that we have the largest or the most stormwater ponds compared to any other community in the City of Tampa? And then the follow-up question was, okay, we have the largest number of stormwater ponds. Why do they look this way? They were considered to be eyesores for many of the residents that live in East Tampa, and so this kind of began the thinking around, okay, well, this is a pain point for residents here, let’s dig into the history, let’s understand why it is that stormwater was built the way it was, stormwater infrastructure, excuse me, was built the way it was in East Tampa. How does this, again, compare to the rest of the city? What were the decision points that led to this observation that we now see as stormwater being eyesores and the largest number of stormwater ponds in this particular community.

0:21:25.4 Dr. Maya Carrasquillo: So just to give you a snapshot, this was a picture that was taken in 2018, so a few years old, but still pretty characteristic of what we would see when we would go around and do an assessment of stormwater ponds in East Tampa. So this notion of these stormwater ponds being eyesores, especially when located in residential areas, which is where the majority of the ponds were, If someone steps outside of their home, they see large ponds, steep slopes, fencing and depending on time of year, a lot of algae growth. And so this kind of characterized a lot of what became the pain point and the source of pain, but again, still that question of what is the history, why are these ponds built this way? And those from the engineering would argue, okay, there were a lot of technical decisions that went into this decision, but as I’m sure this audience knows, that’s not always the case, or there’s still things that lead to decisions being what they are. So in East Tampa’s case, there were a number of decisions that went into it. Part of the research was doing interviews with residents and management stakeholders between the city and also within the community. And so one of the things that came out of it was the rich history in East Tampa.

0:22:45.2 Dr. Maya Carrasquillo: This quote highlights that people tend to think that there’s no buy-in to the community, but that’s not true, there’s a rich, rich history in East Tampa. We had a hospital, at one point a lot of nursing homes that are still in East Tampa, and 22nd Street, which is one of the main through Streets, had a large number of businesses and still does today, and becomes one of the main attraction point for people when they come in and out of the community. So with stormwater ponds being a particular pain point for residents, the residents came up with a solution because they are CRA, they had access to city resources, and so the residents of East Tampa decided, hey, we wanna revitalize these ponds, we want them to be spaces of attraction, we want them to be places where we can take pride in our own neighborhoods. So, shifting forward a few years, residents decided to invest money in revitalizing four of these storm water ponds. These were large beautification efforts, millions of dollars went into each revitalization project. Pictured here are several of the leaders at the time, the then Tampa Mayor Pamela Iorio is pictured here with one of the community leaders and also one of the decision makers at the time on the CRA board, Bishop Thomas Scott.

0:24:02.4 Dr. Maya Carrasquillo: And in this picture where it says Robert L. Cole, Sr. Community Lake, it’s a renaming of the lakes or the ponds from ponds to lakes, so that it could also be not just a space of attraction, but a place that actually honor the legacy of leaders in the community and so pictured here is also Robert L. Cole himself, who the pond was named after. So after this particular pond was revitalized, this is a snapshot of what it looked like after the revitalization effort, so you can see some of the physical infrastructure that was put in. They have is double decker gazebo, there’s actually two that sit on a pond, the decorated rain barrel, and even a sign of better health of the pond itself is the wildlife that’s present. And so this is again, just a snapshot, but really what this project uncovered was the legacy of history and leadership in the decision-making processes, and this question that kind of sparked the research of why is it that our stormwater looks the way it looks. Why is our system built the way it’s built? And one of the things that came out with the interviews with the city in particular was what leads to this idea of infrastructural violence. And so in this tradition, before we jump even to infrastructure apartheid, there’s this legacy tradition of understanding infrastructure from the infrastructural violence comes out of anthropology traditions.

0:25:31.7 Dr. Maya Carrasquillo: And so we understand infrastructure, again, is not just a material embodiment of violence, structural or otherwise, but often it’s instrumental medium in so far as the material organization in form of a landscape, not only reflect but also reinforce social orders, thereby becoming a contributing factor to reoccurring forms of harm. It is the collectively held nature of infrastructure that makes it such a powerful site for not just thinking about society’s responsibility to itself and to each of its members, but also for identifying those who undermine this responsibility about how to build more just cities. Infrastructural violence, again, comes out of this orientation of anthropology, and I stand for this idea that in some cases, official disregard for the urban poor is fundamentally illustrated by inequitable access to basic services and the planning, governance and decision-making processes that sit behind infrastructure provision. These decision-making processes are embedded across multiple layers of governments, agencies and actors in a way that impedes accountability to the public and obscures the responsibility of a state.

0:26:43.4 Dr. Maya Carrasquillo: So again, this comes out of anthropology. So Rogers and O’Neill published this paper and then had a whole call for papers specifically around this topic, but Rogers and O’Neill referred to this phenomenon as infrastructural violence. It’s derived through the concepts of infrastructural power by man, emphasizing institutional regulation of society by elites, infrastructural violence also links up with infrastructural warfare coined by Graham producing infrastructure provision that induces human suffering. So under this tradition of infrastructure violence, characterized as either active or passive, so active infrastructural violence speaks to the conscious development of infrastructure to regulate normative social and territorial relations, articulations of infrastructure that are designed to be violent whether in their implementation or in their functioning, and in particular for it to be characterized as active infrastructural violence, it implies a clear intent to induce harm.

0:27:46.9 Dr. Maya Carrasquillo: Now, passive infrastructural violence is where the socially harmful effects derived from infrastructure’s limitations or omissions rather than its direct consequences, so oftentimes, especially in engineering, we think of this as unintended consequences in particular. So Rogers and O’Neill also state that the concept of infrastructural violence shifts our perceptions, excuse me, from the conventional understanding of infrastructure as material and technical urban systems to infrastructure as social technical regimes. So, infrastructural violence occurs when residents are either excluded from essential infrastructure, such as water and sanitation services by acts of displacement or inadequate infrastructure provisioning. Both denial and exclusion cause human suffering. And so infrastructural violence also takes place through articulations of infrastructure that are designed to be violent. So we are gonna pause here and think this tradition of infrastructural violence, and I teach on this topic, both to grad students and undergrads, and this class in particular, this semester really began thinking and challenging this notion of, okay, well, why does it have to be categorized? And is it maybe harmful to try to categorize infrastructure as either passive or violent?

0:29:06.7 Dr. Maya Carrasquillo: I tend to agree with their thinking on this, and so I wanna get us to think about why is infrastructural violence enough? And the questions that I’ve asked, those question that my students have asked, are thinking about a solution, and are we absolving ourselves and each other from collective responsibility by reducing the articulation of harm to more individualized acts of violence rather than systemically induce? So when we start to even think about how we characterize and define infrastructural violence as either passive or active, how do you determine if someone intended to cause harm, and even as we think about it in terms of individualized acts of racism, does intent negate impact? And I think where we start to dig into this understanding of impact regardless of intent, violent and characterizing infrastructure as violent, in my opinion, I think becomes more insufficient to actually characterize what’s really happening and where our practices have been designed to not only induced harm, but dehumanization. So infrastructure apartheid and thinking about it from this orientation comes from the tradition and maybe some of the language that’s used in a couple other spaces.

0:30:27.7 Dr. Maya Carrasquillo: So food apartheid and I have to give a shout out to Julian because he actually was the first person to challenge my framing from infrastructure deserts and to really begin thinking about infrastructure apartheid. And so food apartheid coined by Karen Washington, this quote from her says, “When we talk about food apartheid, the reason why we bring it up is because food desert doesn’t cut it, food desert doesn’t open up the conversation that we need to have when it comes to race, when it comes to inequality, when it comes to so much.” So food desert is defined by USDA as a low-income census tract where either a substantial number or share of residents has low access to a supermarket or a large grocery store. The term is inadequate because the term implies that a lack of affordable and fresh foods is just a geographic problem. The word desert makes it seem like these communities are lacking when they are actually filled with life, and then the term makes the problem of food access and security seem like a natural phenomenon and absolves responsibility.

0:31:28.5 Dr. Maya Carrasquillo: There’s also the framing of eco-apartheid, which was first coined by Van Jones in 2007. So eco-apartheid defines a situation which White and affluent communities reap the tremendous benefits of clean and green economic development, while communities of color fall further behind in a state of eco-apartheid benefits of the new economic activity that the green wave generates will bypass the very communities most in need of new investment, new jobs, and a better environmental stewardship. So this is the original quote from Van Jones. A colleague and friend of mine, Dr. Antwi Akom extended this definition a bit further and he quotes saying, “Although powerful Jones’s definition of eco-apartheid’s constructed as if it were a socio-economic phenomenon, that could happen to communities of color in the future, rather than an ecological component of structural racialization that began in the past is happening in the present and is informing the future.” So an eco-apartheid approach helps to illuminate the ways in which historical legacies, individual structures and institutions work together to distribute material and symbolic advantages and disadvantages along racial lines.

0:32:47.2 Dr. Maya Carrasquillo: I wanna revisit this slide. These are accepted characteristics of infrastructure that we spoke about a little earlier. So as a reminder or a refresher, these characteristics include infrastructure is not just material entities as embedded as transparent, they link with conventions of practice, embodiment of standards and become visible upon whenever we visit the slide, because this kind of spurred a lot of the thinking and maybe some of the challenging about framing…

0:33:20.0 Julian Agyeman: Hi, Maya, you’ve frozen. Maya, you’re back.

0:33:24.0 Dr. Maya Carrasquillo: I’ll take it from the top of the slide ’cause I think that’s maybe where I got cut off. So just to reiterate, thinking about infrastructural apartheid, as systemic dehumanization through material and social entities that are observed, felt and lived across racial, economic and geographic spatialization, if we kinda go through the characteristics of the accepted characteristics of infrastructure, thinking about infrastructure as it is established, it is therefore embedded through existing and interlocking systems of domination, oppression and dehumanization, challenging this notion of infrastructure being transparent to those who are most affected by its presence, whether positively or negatively, it is seldom if ever transparent. Its links with conventions of practice is the very thing that reproduces harm, violence and warfare when embodying these standards that were built by and for the dominant majority through historically, colonialism imperialism, racism, sexism, all of the isms can go on and on and on. And this idea of it becomes visible upon breakdown. Its breakdown, I would argue, is perpetually visible in experience because it is a broken system built on broken standards and conventions of practice. And so again, as we kind of lean into this tradition of thinking about infrastructure from an apartheid understanding rather than one that is violent, it removes this idea that with different actions, the outcomes can be shifted.

0:34:55.3 Dr. Maya Carrasquillo: I think when we say violence, it puts too much onus on individual decision makers and decision making, and once we start to… To a broader understanding, even if originally intended with this infrastructural violence framing to one of apartheid, I think it actually better characterizes… I guess I had it on the next slide, the legacy of understanding of infrastructure through violence and warfare speaks more to the effects of the system and how we experience it rather than what causes our experiences with the system to be hurt and our responses to the system to be one of outrage. So again, this is my ever-evolving thinking of this topic, it’s quite interesting, situated, being situated in an engineering department and approach in this way with this vantage point. And happy to share more about that if you have any additional questions. So characterized structural apartheid, how we’re thinking about it. Where do we go from here? In the words of Dr. MLK. So really just wanted to spend the last few minutes with you all to share a little bit about my research lab, as Julian mentioned in her bio.

0:36:16.0 Dr. Maya Carrasquillo: We are the Liberatory Infrastructures Lab, originally changed the name from Jedi lab to Liberatory Infrastructures because I thought Liberatory Infrastructures better characterize what we are striving towards, this idea of liberation, even pushing beyond just justice, for us to really think about what does it look like to build on a foundation of love, liberation and restoration, particularly for those who have been historically subjected to under-resource and marginalization across legacy and time. So our works kind of spans these four application areas, if you will. So I’ve mentioned before food, energy, water, more recently, and I guess by default of me being in engineering data science just happens to be one of the major areas that our work is also spanning to, which is not a space I thought I would end up in, but research always takes you in unique ways and in different pathways. So all of our work is community-grounded, we have very rich partnerships, I’ll go through a few examples and some of the projects that we’re working on within the same thinking of apartheid characterization of infrastructure and recognizing that a systems theory approach is actually what helps to situate it.

0:37:36.9 Dr. Maya Carrasquillo: We engage in the practice of systems thinking and analysis across all of our projects, which helps to frame a lot of the theory and frameworks that we use to really ground our scholarship, especially with engineering. And then thinking about what this looks like in translation, so beyond just the academy, how does this translate to practice and policy and the broader education of engineers as well. So this is my lab, love to highlight them. I think it’s not just about the work that we’re doing, but who is doing the work and getting a chance to create space for a lab that is predominantly women of color is really what motivates a lot of this work. And probably unsurprisingly, a lot of the thinking and the framing of the work as well.

0:38:24.0 Dr. Maya Carrasquillo: And so it’s such a joy to be able to work with a large group of women of color in engineering and across campus who are thinking about this work with a very just focus. So just to highlight, I’m gonna go through three projects pretty quickly. So probably the closest project that is aligned with previous work that I highlighted is this Green Stormwater Infrastructure by and for Communities. It’s funded by EPA’s Water Quality Improvement Fund, which is an interesting grant to be on as an academic because it is not a research grant. But it also, it opened up the door to work with some really great partners in the Bay Area. So San Francisco Estuary Partnership, two community organizations based in Richmond East Oakland, respectively, Urban Tilth and Hood Planning Group.

0:39:09.5 Dr. Maya Carrasquillo: And then the Research Center, San Francisco Estuary Institute and our lab and a very large and multi-faceted project. But really the idea, and particularly from our vantage point is, as Engineers, we bring a unique perspective. And as we think about Green Stormwater Infrastructure beyond planning, this really is an implementation, design and implementation-based project. And so we’re really trying to challenge how do we actually think about what it looks like to incorporate community perspectives and standards into design criteria for Green Stormwater Infrastructure. And so again, very multi-faceted project. The goal coming out of this, particularly for the City of Richmond and Oakland over the next four years, is to develop this community-led neighborhood GSI plan, and hopefully lead to some revitalization and/or implementation projects between both of these communities, respectively.

0:40:03.4 Dr. Maya Carrasquillo: I’m really excited to highlight this project. So my most senior PhD student, Bhavisha Kalyan, is finishing up her work and really situated it within the community of Newark alongside an activist group, the Newark Water Coalition. Her work started with this idea, and similarly thinking about answering the question that the community organization was posing. So in this case, it was, where is lead and how are we being exposed to it? And so through this process, she… Oops. Wrong direction. Here we go. So through this process, alongside the Newark Water Coalition, they established and they developed a mobile lead testing unit, went around to, I believe it was about 350 households, testing water, paint, soil, and dust samples across the city of Newark. This work has gained quite a bit of traction.

0:40:58.3 Dr. Maya Carrasquillo: So they’re actually replicating a couple of mobile lead testing units in two other New Jersey cities. And this idea that in this particular project, so much of her research was driven by the community, but then also alongside. And so there was an opportunity to train high schoolers, local college students that were back home for summer breaks. And so this has been a very integrated project that has led to, most recently, the publication of a community voice paper in the Environmental Justice Journal in their special issue for liberation science. So really proud of this work and the work that she’s gonna be doing and hopefully we’ll be able to continue as a future faculty.

0:41:44.0 Dr. Maya Carrasquillo: The last project that I wanted to highlight is probably the newest in terms of timing, but then even thinking. So one of my students, Jasmine McAdams, is a member, is a PhD student in our energy resources group. And she is really interested and motivated by thinking about the impact of energy grid disruptions for incarcerated populations. She has personal motivations for wanting to do this work, but we’ve been really motivated. And as we’ve been digging into this topic in particular, I wanna highlight this book by Judah Schept, “Coal, Cages, Crisis.” And it really speaks to this trade-off between this just energy transition and how that has actually become a mechanism for implementing or building prisons in Central Appalachia.

0:42:34.5 Dr. Maya Carrasquillo: So her work is taking an interesting form and probably going to have more of a political economy framing, but really excited about the different methods that she’s going to be using. And I think the framing and helping us to challenge even some of the norms of how we’re thinking about climate and what are just transition that we’re making for climate impacts. But what are the trade-offs that we have to think about as we’re engaging in this work and for whom. I’m kind of getting back to this, who is still being excluded, even in our attempt to implement environmental justice.

0:43:09.5 Dr. Maya Carrasquillo: Admittedly, don’t really have major takeaways from this other than, like I said, this is an evolving framing. The ongoing question in my brain, and I’m sure for others as well as you’re listening to this is, how do we, especially again being situated in engineering, reconcile the legacy of engineering and infrastructure apartheid with this hopeful, idyllic aspiration to embed love, liberation, and justice into the systems that we create? And is this possible, or do we have to just burn the whole system down? I don’t know.

0:43:39.4 Dr. Maya Carrasquillo: Again, it’s an evolving space of thinking and research for me and my group, but really excited to answer any questions or just have a conversation about that. And then, as I mentioned, we’re just continuing to expand our research. Well, my students are really digging into their projects and so excited to see where it goes, and I think really challenging the legacy of dehumanization in our field and in our practice and how we build systems and just challenging the conventions of what do we consider to be critical infrastructure, how do we think about critical needs, and for whom, in the process of not just doing research, but in practice as well.

0:44:18.4 Dr. Maya Carrasquillo: So I’ll leave with this this last scripture, “Learn to do right, seek justice, defend the oppressed, take up the cause of the fatherless, plead the case of the widow,” and again, this point to really hit on defend the oppressed, this is, I think, more timely than not to really think about how we situate not only our work but ourselves in the world that we are existing in today, and so this continues to be my motivation, this continues to be the scripture that my lab’s work is founded on and so I’m excited to continue this thinking and just to continue to try to bring this good work into the world of academia. Anyway, I’m gonna take a sip of water. Thank you all for listening. Happy to take any questions.

0:45:09.1 Julian Agyeman: Well, Maya, what a fantastic trip. I could have spent a couple more hours having you unpack a lot of the things in there. There’s so much rich work. And I’m proud that our chance conversation in Toronto led to you rethinking the notion of desert to one of apartheid. And I think you should get tenure on that alone, okay? If you don’t, I’ll be writing to the Regents Of The University Of California. Okay, we’ve got some questions.

0:45:42.4 Dr. Maya Carrasquillo: That’s recorded. So just, so y’all are witnesses to that. Julian is gonna write a letter to you. [laughter]

0:45:49.2 Julian Agyeman: Hey, I’ve written to the Regents Of the University Of California before. I’m a nuisance in their eyes. Okay, first question from my friend, Deb Guenther from Mithun in Seattle. What are the aspects of your work that seem to resonate with the average engineer?

0:46:05.6 Dr. Maya Carrasquillo: Hmm. That is a great question. I’m chuckling. So one of my students just went through prelim on Monday, and that was one of the comments that came up. It’s like, “Oh, how does this connect to the engineering coursework?” You know, and I think this is actually what motivated the shifting to infrastructure broadly. I think as we begin to situate the work in this convention of design and recognizing that, hey, we have design criteria, there are standards that we have to adhere to and all the things that engineers like to say. The more we can make this a standard practice, at least my hopeful thinking is, if it becomes standard, then it becomes convention and that becomes how we operate. I don’t know that I can say that my work resonates well with engineers. [laughter] Probably not very surprising. But I think if nothing else, especially at least within Civil and Environmental Engineering, you will find that most people who get into this particular subfield of engineering are very altruistic. Almost everybody has entered into the space because they wanted to make the world a better place, in whatever respective tradition they find themselves in.

0:47:20.9 Dr. Maya Carrasquillo: And so that being the motivation for the work, I think even those who may not fully get it, they have questions and they’re interested because it gets back to their core of, I wanna make the world a better place with engineering, and this is how we can maybe do this. So that’s my long answer to your question. But yeah, definitely challenging some of the conventions in engineering. And as you can imagine, there’s some pushback and maybe some reluctance to do that.

0:47:46.0 Julian Agyeman: Great. Thanks. We got a question from Sharon. Do you work with communities who are reclaiming spaces for growing food or even just re-vegetating to avoid urban heat islands?

0:47:57.8 Dr. Maya Carrasquillo: Yes. So that’s some of the motivation for the GSI by and for communities project. Both locations in Central and North Richmond and deep east Oakland are very concrete, not a lot of green space, a lot of challenges around air pollution. So even just being able to work alongside communities that recognize that as a pain point. And even though small interventions and decentralized interventions at the very least, we can articulate and work alongside them to understand, hey, this is something that can help with capturing poor air quality or help alleviating urban heat islands. And so that is one of the things that we are thinking about for that particular project. I think there was another part to that question, but hopefully that I got to, most of it.

0:48:46.1 Julian Agyeman: We’ve got another question here. This is quite a long one from anonymous participant. Anonymous participant, because you’ve asked a good question, I’m going with this, but we do like to actually see names, FYI, in the future for obvious reasons. So anonymous participant says, “Thank you. Curious about how an analysis of colonialism and particularly the concept of predatory inclusion complicates our understanding of infrastructure apartheid from a grassroots praxis perspective. Can you discuss the conflict between when ethical reconciliation of infrastructure development is feasible/worthwhile versus situations in which obstructing colonial development may be the most strategic move towards a more just world outcome, e.g., do we need equitable distribution of oil infrastructure or to keep fossil fuels in the ground?” I think that’s the longest question.

0:49:40.8 Dr. Maya Carrasquillo: Great question.

0:49:42.9 Julian Agyeman: Yeah.

0:49:43.9 Dr. Maya Carrasquillo: Long but beautiful question.

0:49:45.7 Julian Agyeman: Sure.

0:49:46.9 Dr. Maya Carrasquillo: That is… I love that question so much because it kind of gets to the core of one of the things that I challenge my students to think about is, so engineers, our tradition is build, build, build, build, build. [laughter] And the question really is, does it need to always come down to building something? I think even the legacy and the tradition of engineering is being so focused on building more, building more, like you said, has its roots in colonialism, imperialism. There’s constantly this lack mentality of we don’t have enough. So even that notion, you’re absolutely right.

0:50:23.1 Dr. Maya Carrasquillo: And I think even as we think about infrastructure apartheid, being that built infrastructure has led to these legacies. The question really that we start with is, do we need to build? And if not, what does restoration, what does justice in this context look like? It doesn’t always need to be a large infrastructure project that’s going to cost billions of dollars that we’re probably going to need to tear up in 50 years anyway. And that’s honestly where we kind of get out a lot of the work. And one of the richness about working alongside partners in this is that we as engineers get to challenge the notion amongst our own community that we don’t always need to build. And that doesn’t need to be the solution in how we approach this work.

0:51:00.4 Julian Agyeman: Okay.

0:51:02.4 Dr. Maya Carrasquillo: Hope that answers the question

0:51:02.5 Julian Agyeman: I’m just noticing a couple of questions about recording. Yes, this will be recorded. Tom, can you resend the link, the shareable link, if it’s available? This will be both a podcast and this direct recording that you see here. We’ve got a question from MT. Hi, as a young Black and disabled person with no background in engineering, but rather heal in justice and learn stewardship, I’m wondering if you have advice for how to learn more about technical liberatory engineering. Are there programs or mentorship opportunities you know of? Thanks so much for your work. And everybody is saying, thanks for your work, Maya. So, you’re on the right track.

0:51:45.5 Dr. Maya Carrasquillo: Good to hear. [laughter] I think, admittedly, I’m struggling with the question, and I think maybe it’s… The framing of it is technical liberatory engineering. I wanna call this out ’cause this is often what I hear sometimes in the discipline, and you know, there’s times that technical, I think is weaponized to maybe demean the nature of the work. I argue that if this helps us to do our traditional technical work better, it is inherently technical. I’ve worked with systems, I’ve worked with people, people are far more complicated. And so thinking about this work and even a qualitative orientation even that my group takes to unpack some of these realities, I would argue that that is the technical liberatory engineering that we’re really leaning into.

0:52:40.3 Dr. Maya Carrasquillo: And I think for those of us who are in this space, be it characterizes equity, justice and engineering, most of us young, junior assistant professors on the tenure track, most, if not all of us have that same orientation where we do very deep community-engaged work, and that becomes the substance of the technical scholarship that we’re bringing to the field. Hope that answers your question.

0:53:06.5 Julian Agyeman: Great, thanks. We have a question from Meredith Levy, Tufts alumni and doing great work in the Boston Metro area, great presentation. Since many of these infrastructural systems are inter-tangled and one relies on the other, how do you begin to unpack that, to un-track, redress the resulting apartheid?

0:53:33.1 Dr. Maya Carrasquillo: That is a great question and a very complex one that admittedly we are still exploring. I think the short answer is, this is why we take a systems approach to it, and systems thinking, systems theory in and of itself is flawed to some degree or limited, I should say, not flawed, but limited in the extent that in the traditional way that We think about systems thinking and framing, there needs to be some bound on the system in order to really be able to analyze it, that has its limitations. But from a practical standpoint, that is how we begun to think of the work. What does that look like to disentangle that when you actually transition it from academic scholarship to practice is a totally different beast and not one that admittedly we have an answer to yet.

0:54:25.2 Julian Agyeman: Right. Okay. I think we’re just about out of time, but let me just… We do have a question from La Trecchia who is in Tampa and who is a professor at the University of South Florida.

0:54:42.4 Dr. Maya Carrasquillo: Awesome.

0:54:43.5 Julian Agyeman: Where she founded the Environmental… I love your work and I’m fascinated by what you shared about East Tampa and food apartheid. I’ve reflected on this quite a bit lately. I regularly shop in the Sanwa Farmer’s… In East Tampa, which seems to be a critical resource for disadvantaged communities. So more of a pointer than a question. So that really resonated. We are out of time now, so our next Cities@Tufts session will be on the 6th of December, where Dr. Dana R. Thomson will present on co-design in global development data initiatives. Maya, fantastic presentation. I am gonna be watching your work as I’m sure many of our people are. I want people in the watch room, the UEP Urban planning students, what are the implications of infrastructure apartheid, Maya’s Fantastic work, for urban planning? Let’s start thinking about that, and if anybody wants to do some research with me on what are the implications, email me and let me know and we’ll link in with some of the work that Maya is doing, and let’s see what the urban planning response could be.

0:56:00.1 Julian Agyeman: Could we offer something to a simple engineer who is trying to understand all of these issues? Again, Maya, thanks. Can we give a round of applause for Maya Carrasquillo?

0:56:15.7 Dr. Maya Carrasquillo: Thank you, Julian. Thank you, everyone. It’s been a pleasure.

0:56:17.2 Julian Agyeman: Stay safe, everybody. See on the 6th.

0:56:19.8 Dr. Maya Carrasquillo: All right.

[music]

0:56:25.7 Tom Llewellyn: We hope you enjoyed this week’s presentation. As Julian mentioned, our next lecture, co-design and global development data initiatives with Dr. Dana R. Thomson will take place on Wednesday, December 6. Click the link in the show notes to register for a free ticket. Cities@Tufts is brought to you by Tufts University and Shareable with support from the Barr and Shift foundations. Lectures are moderated by Professor Julian Agyeman and organized in partnership with research assistants, Deandra Boyle and Muram Bacare. “Light Without Dark” by Cultivate Beats is our theme song. Robert Raymond is our audio editor. Additional communications, operations and funding support are provided by Paige Kelly, Alison Huff and Bobby Jones. And the series is co-produced and presented by me, Tom Llewellyn. Please hit subscribe, leave a rating or review wherever you get your podcasts and share with others so this knowledge can reach people outside of our collective bubbles. So for this week’s show, here’s the final thought.

0:57:20.6 Dr. Maya Carrasquillo: As we kind of lead into this edition of thinking about infrastructure from apartheid, understanding rather than one that is violent, it removes this idea that with different actions, the outcomes can be shifted.

[music]