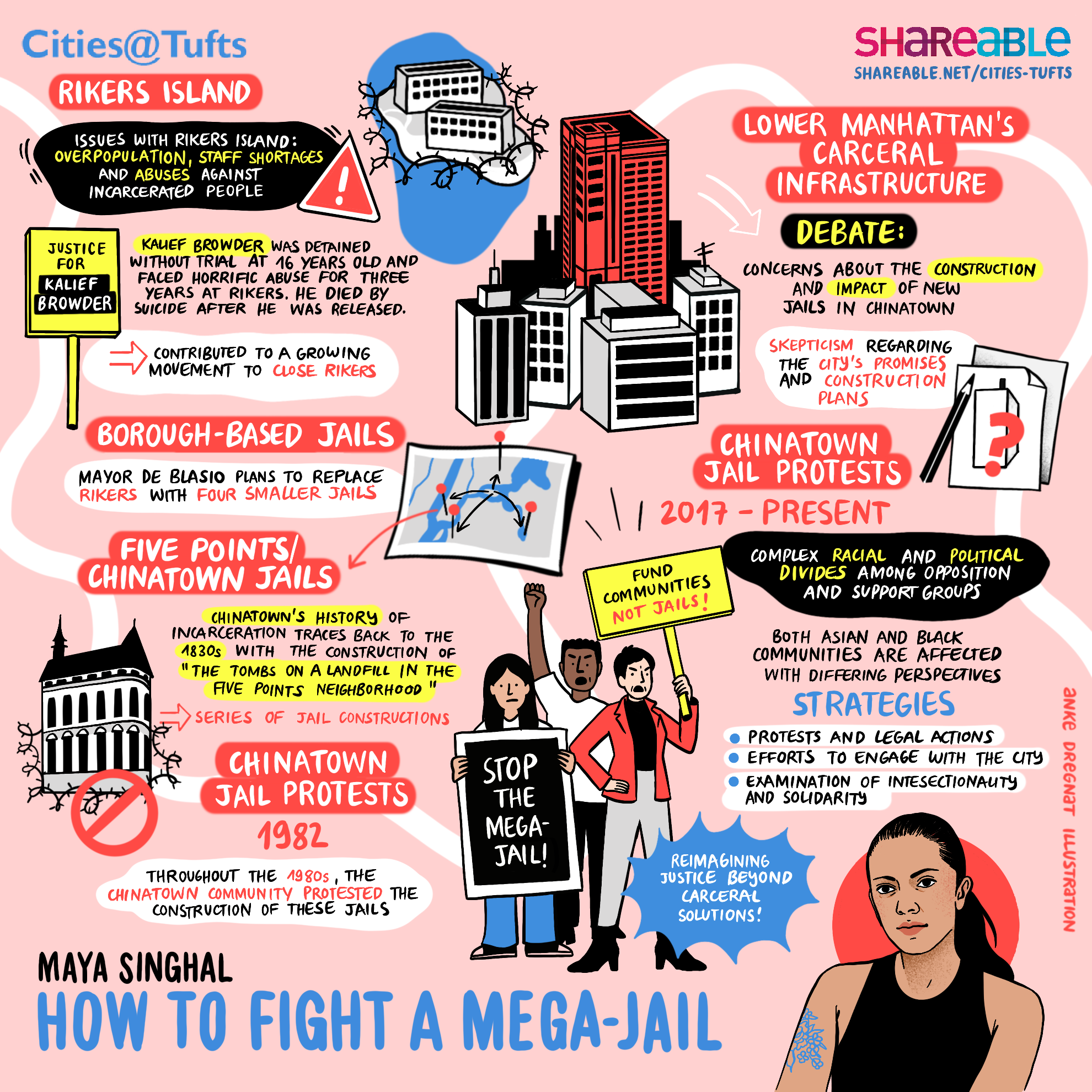

In 2017, New York City committed to a plan to close Rikers Island Jail Complex and build four smaller jails around the city in Manhattan’s Chinatown, Downtown Brooklyn, Mott Haven in the Bronx, and Kew Gardens in Queens. The Chinatown jail is planned to be built on the site of the current jail in the neighborhood, but rather than repurposing or remodeling the building, the city plans to demolish it and build a 300-foot mega-jail, which would be the tallest jail in the world. The fight against the new Chinatown jail has drawn together a diverse coalition concerned about the effects of the jail on the Chinatown population and the predominantly Black and Latine populations incarcerated inside it. This episode of Cities@Tufts explores how concerned groups are working to bridge their differences and develop strategies to fight the new jail construction.

Maya Singhal is a Postdoctoral Research Associate at the Center for the Study of Race and Ethnicity in America and the Watson Institute for International and Public Affairs at Brown University. They completed their PhD in Anthropology at Harvard University, and they also hold MA degrees from the University of Chicago and New York University and a BA from NYU. Singhal’s research is interested broadly in how people navigate violence across generations. More specifically, their recent work deals with crime, capital, and mutual aid in African and Chinese diasporic populations. Singhal’s current book project is an ethnographic and historical study of African American and Chinese American self- and community defense in New York City and the histories of extralegal neighborhood protection (e.g. gangs, neighborhood patrols and associations, etc.) that inform these present-day efforts towards safety.

About the series

Shareable is partnering with Tufts University on this special series hosted by Professor Julian Agyeman (Co-chair of Shareable’s Board) and Cities@Tufts. Initially designed for Tufts students, faculty, and alumni, the colloquium has been opened up to the public with the support of Shareable and Barr Foundation.

Cities@Tufts Lectures explores the impact of urban planning on our communities and the opportunities to design for greater equity and justice.

Register to participate in future Cities@Tufts events here.

Listen to the Cities@Tufts Podcast (or on the app of your choice):

How to Fight a Mega-Jail Transcript

[music]

0:00:10.5 Maya Singhal: Taking seriously concerns about the spatial impacts of the jail on Chinese communities can help us to evaluate the limitations of promises of ethical jails and the anti-Black racism of mass incarceration reform. It should prompt us to push for better futures than allegedly more ethical mega-jails, to instead imagine a world where we do not put people in cages and burden communities with housing these institutions.

0:00:35.9 Tom Llewellyn: Welcome to another episode of Cities@Tufts Lectures where we explore the impact of urban planning on our communities and the opportunities designed for greater equity and justice. This season is brought to you by Shareable and the Department of Urban and Environmental Policy and Planning at Tufts University with support from the Barr Foundation. In addition to this podcast, the video, transcript and graphic recordings are available on our website, shareable.net. Just click the link in the show notes. And now, here’s the host of Cities@Tufts, Professor Julian Agyeman.

0:01:10.4 Julian Agyeman: Welcome to our Cities@Tufts Virtual Colloquium. I’m Professor Julian Agyeman, and together with my research assistants, Deandra Boyle and Muram Bacare, and our partner, Shareable and the Barr Foundation, we organize Cities@Tufts as a cross-disciplinary academic initiative, which recognizes Tufts University as a leader in urban studies, urban planning and sustainability issues. We’d like to acknowledge that Tufts University’s Medford campus is located on colonized Wampanoag and Massachusett traditional territory. We’re delighted to host today Dr. Maya Singhal. Maya is a postdoctoral research associate of the Center for the Study of Race and Ethnicity in America, and the Watson Institute for International and Public Affairs at Brown University.

0:01:57.8 Julian Agyeman: They completed their PhD in anthropology at Harvard University, and they also hold MA degrees from the University of Chicago and New York University, and a BA from NYU. Maya’s research is interested broadly in how people navigate violence across generations. More specifically, their recent work deals with crime capital and mutual aid in African and Chinese diasporic populations. Maya’s current book project is an ethnographic and historical study of African American and Chinese American self and community defense in New York City, and the histories of extra legal neighborhood protection through gangs, neighborhood patrols, associations, et cetera, that inform these present day efforts towards safety. Today Maya is gonna talk about her doctoral research, How to Fight a Mega-Jail. Maya, a zoomtastic welcome to Cities@Tufts.

0:02:58.7 Maya Singhal: Thank you so much, and thank you for inviting me, Julian, and Deandra and Tom for all your help organizing and putting this together. So I guess I’ll just begin. Oh, and I’ll say that also, I’m currently a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Chicago, so I actually left Brown last semester. This talk is called How to Fight a Mega-Jail, but that title is somewhat misleading. I am going to talk about strategies that people in New York City have taken to fight the promise of a 300-foot tall jail in Chinatown. However, as yet, these strategies have merely stalled the project. Demolition is well underway on the old jail paving the way for the mega jail construction to come. I was initially interested in the Chinatown Jail because of the diverse coalition opposing it. From abolitionists to conservative business owners and across the spectrum of age and race, many people around lower Manhattan have voiced their opposition to the jail construction.

0:03:57.3 Maya Singhal: However, since 2020 and the Movement for Black Lives and Stop Asian Hate, the racial politics of the jail plan and its locations have become both more explicit subjects of debate and somewhat more complicated. Chinatown is often portrayed as an ethnic enclave, a neighborhood filled with prejudiced immigrants who do not take kindly to outsiders and especially Black and Brown ones. Yet tense coalitions have been built between abolitionists concerned about the effects of carceral expansion on Black and Brown people, and those who feel that the new jail will both embody and invite anti-Asian violence. On the other hand, the jail plan has also found vocal supporters in many Black communities for reasons I’ll talk about in a minute. And many in this group read the opposition to the Jail from Chinese people as indicative of Chinatown’s anti-Blackness.

0:04:46.8 Maya Singhal: In this talk, I’m going to discuss the Black and Chinese coalitions and conflicts that have been developed through debates about the city’s jail plans. I wanna trouble neat narratives about racial and political divides. Instead, it seems to me that support and opposition to the jail has split groups less along racial lines than by what I can only describe as trust in government. As the city tries to garner support for the jail plan, it’s promising increased business, investment in the neighborhood, more humane jail conditions, support for incarcerated people, and easier access to the jails and courts. However, the city’s track record for keeping their promises in the jails is spotty at best. But now I’m getting ahead of myself. So to understand debates about… Excuse me, around the Chinatown Jail, we first have to discuss the city’s current jail system, much of which is based on Rikers Island, the 2019 borough-based jail plan, and the history of jails in Chinatown.

0:05:47.4 Maya Singhal: On May 15th, 2010, a 16-year-old African American teenager named Kalief Browder was arrested for allegedly stealing a backpack. Browder was held on Rikers Island without trial for three years, about two years of which he served in solitary confinement. During this time, he was exposed to extensive violence from other incarcerated people, as well as from the Department of Corrections or DOC guards. Finally, during a stint in solitary, in 2012, Browder attempted to end his life. It was the first of several attempts during and after his incarceration. In 2013, Browder’s case was dismissed without a trial or a verdict. And on June 6th, 2015, Browder committed suicide in his home at the age of 22. The most unique thing about Browder’s case was the publicity it received, which contributed to a growing movement to close Rikers. Rikers Island Jail Complex opened in 1932 and has been criticized heavily since for overpopulation, staff shortages, and abuses to its incarcerated population.

0:06:47.9 Maya Singhal: In a 2019 report, the US attorney wrote that quote a deep-seated culture of violence is pervasive throughout the adolescent facilities at Rikers, and that adolescents incarcerated there have sustained a striking number of serious injuries, including broken jaws, broken orbital bones, broken noses, long bone fractures, and lacerations requiring sutures. Further, the report cautioned our focus on adolescent population should not be interpreted as an exoneration of DOC practices in the jails housing adult inmates. Our investigation suggests that the systemic deficiencies identified in this report may exist in equal measure at the other jails on Rikers.” Adolescents were removed off the island in 2018 as part of the effort to improve conditions. However, concerns still remain for Rikers incarcerated adult populations. Rikers Island Jail Complex currently consists of eight facilities housing more than 6000 incarcerated adults, almost 90% of whom are being detained pretrial.

0:07:47.7 Maya Singhal: According to the Center for Court Innovation, people with felony indictments wait an average of 10 months for their cases to be resolved unless they go to trial instead of taking a plea deal, in which case they wait an average of a year and a half. According to the Vera Institute, 30 people have died in New York City DOC custody or immediately following their release since the beginning of 2022, including two people already this year. So in 2017, then Mayor, Bill de Blasio pledged to close Rikers, and two years later, the New York City Council approved a plan to replace it with four smaller jails in Chinatown, Manhattan, Downtown Brooklyn, Kew Garden’s, Queens, and Mott Haven, Bronx by 2027. The plan is currently estimated to cost more than $8 billion, although that figure is sure to increase as construction begins. The Chinatown Jail is planned to be built on the site of the current Manhattan Detention Complex, which you can see here on the right, but there’s been a jail in Chinatown since the neighborhood was called Five Points.

0:08:46.5 Maya Singhal: Before it was Five Points, the land was Collect Pond, which was filled poorly in 1817. Originally a place where African Americans lived on the border of the city, Five Points became an immigrant neighborhood, first for Irish and German populations, then for Italians, Eastern Europeans, and finally by the 1870s, the Chinese. The Halls of Justice were built on the swampy Five Points landfill between 1835 and 1840 to replace the Colonial-era jail in City Hall Park. You can see the picture of that on the left. Resembling an Egyptian mausoleum, the prison was quickly named The Tombs, and that nickname has long outlasted the building, which started sinking only five months after it opened. The darkness and dampness, not to mention the structural problems of the sunken building were not enough to stop the city from incarcerating more than 400 people at a time in a building originally designed to house 200 by the 1880s.

0:09:40.7 Maya Singhal: By the early 1900s, the Halls of Justice were replaced by City Prison, which you can see here in the middle, which was in turn replaced by the 1940s by the Manhattan House of Detention. In 1974, the Manhattan House of Detention closed due to a lawsuit over conditions in the jail. And in 1983, the Manhattan Detention Center opened in its place. Another tower in the center was built in 1990 after the city was ordered to close the Men’s House of Detention on Rikers Island. Throughout the 1980s, the Chinatown community protested the construction of these jails. In fact, in 1982, the New York Times reported that 12,000 people marched from Chinatown to City Hall to protest the Manhattan Detention Center plan. According to one lifelong neighborhood resident, the impressive turnout was achieved by the neighborhood’s restaurant and sweatshop owners pushing their workers to join the protest. As the New York Times explained, resistance was primarily mounted on the basis that the neighborhood already has its fair share of carceral institutions.

0:10:47.6 Maya Singhal: Today, opponents of the Chinatown Jail make much the same argument. Chinatown and its immediate surroundings are home to the NYPD’s Manhattan Central Booking, NYPD headquarters, city, district, and county courthouses, and two jails. So they insist that they should not be labeled as NIMBYs, an acronym for Not In My Backyard. Rather, they ask why predominantly White neighborhoods cannot house more of this carceral infrastructure. Furthermore, many Chinatown residents worry about the effects the jail construction process and the day-to-day use of the new building will have on the neighborhood. The current Manhattan Detention Center already casts a long shadow over Columbus Park, one of the few open spaces for recreation in the neighborhood. Originally, the new building was planned to be 450 feet tall, but Chinatown City Council members fought to reduce the height to 300 feet to keep it closer to the height of the criminal court next door.

0:11:43.7 Maya Singhal: The new building is also planned to have fewer beds than the current detention center, but will supposedly have more therapeutic beds and resources for incarcerated people. The Brooklyn, Queens, and Bronx Jail similarly had height reductions in the plans in 2019. However, now that demolition and construction on the jail sites is underway, some of these plans seem to be shifting. In an attempt to fit more beds into the Brooklyn jail, many of the promised therapeutic beds will be removed and the building’s height will be increased by about 40 feet. Chinatown residents worry these changes foreshadow similar ones for the Manhattan jail. Many are also concerned about the city’s ability to construct such a large building on the precarious landfill without impacting the surrounding apartments. While some business owners have come to support the jail plan in hope that jail staff and the families of incarcerated people will bring additional business to the neighborhood, other people worry that the jail will create too much congestion and parking shortages in Chinatown’s narrow streets.

0:12:42.6 Maya Singhal: Many in Chinatown also speculate about the financial incentives for the borough-based jail plan. They argue that the jail plan was pushed through the City Council without conducting proper studies of the land or exploring the option of remodeling the current Manhattan Detention Center building, which is only a few decades old. Given the city’s haste to construct a completely new building, many have speculated about the influence construction companies have had on the city’s plans. The new jails are also being constructed under design-build contracts, meaning that a company will be awarded the contract before they design the buildings, although the companies will still have to have the plans approved by the city before construction begins. People have a range of concerns over design-build contracts in general, but especially for projects as complicated as these jails, they worry that these contracts often go over budget and that the work quality can sometimes suffer because in this kind of contract, the engineer works for the contractor instead of for the client.

0:13:40.0 Maya Singhal: So in short, the clearest winners in the jail plan are the construction and demolition companies. But meanwhile, many people from Black and Brown neighborhoods most affected by mass incarceration have actually argued in favor of the borough-based jail plan. One person formerly incarcerated on Rikers told me the plan gives him hope that incarcerated people will be treated better with the oversight of their communities rather than being out of sight and out of mind on Rikers. He said that many people he knows also look forward to more easily visiting their incarcerated friends and family in the neighborhood jails. Family members of currently incarcerated people have expressed hope for the new jails design plans to make the entrances and visitors rooms more welcoming. Other formerly incarcerated people believe that there will be less violence when people from different boroughs can be incarcerated separately, and some public defenders support the plan because the borough-based jails will make it easier for them to see their clients and for their clients to be transported to court.

0:14:39.9 Maya Singhal: However, even the most proponents of the plan agree that the promise of replacing Rikers with borough-based jails will not be effective unless the city’s jails are put in federal receivership to remedy the systemic problems of the DOC. While receivership might help address some of the corruption and violence in the DOC, there’s a level of violence that is also just inherent to incarceration. As such, the original borough-based jail plan hinged on dramatic decarceration from 9400 people in 2017 to 5000 by 2026 when the new jails were originally supposed to open. When the plan was announced in 2019, there were about 7100 people in the city’s jails and prison abolitionists wrote a slew of articles in Op-Eds arguing that given record low crime and incarceration rates, there was no need to build new jails. The founder of the closed Rikers campaign, Glen Martin asked, given the dramatic reduction in the prison population, why the city even needed 5000 new beds, there are already currently approximately 2800 beds in our borough jails.

0:15:46.3 Maya Singhal: Martin wrote, if we’re truly aiming for decarceration, we should not grow that number. As Ruth Wilson Gilmore has noted, there’s a long history of using overcrowding as an excuse to build more jails and prisons, which are quickly filled to the point of overcrowding. Increased jail and prison construction has historically preceded increased incarceration, rather than being a response to crime. Abolitionists worry that borough-based jails would be constructed, but overcrowding would be used as an excuse to keep Rikers open leading to even higher incarceration rates. This possibility has seemed especially probable since Eric Adams became mayor of New York. Opposition to the borough-based jail plan has also been mounted from non-abolitionist groups around the city, but particularly from Chinese Americans in Chinatown and African Americans in the Bronx. The jail site in Mott Haven in the Bronx is located in the middle of a plan by Diego Beekman Mutual Housing to improve the neighborhood through affordable housing and economic opportunities.

0:16:48.2 Maya Singhal: Arline Parks, the CEO of Diego Beekman had planned to acquire the NYPD tow yard where the jail is planned to build mixed income housing, a supermarket and other community resources. In Chinatown, the opposition has been headed by Neighbors United Below Canal, or NUBC, an organization, excuse me, founded in 2019 by Christopher Marte, an African Dominican New York City Council member, and Jan Lee and Howard Huie, two Chinese American Chinatown landlords in residence. NUBC has organized protests and information sessions about the jail, and they’re working with architects and engineers to understand and explain the effects the jail construction might have on the neighborhood. As demolition continues, the organization has collected complaints from Chinatown residents about the noise and dust, and concerns about their large cranes that loom over their apartments. Their strategy for their campaign has often prompted them to focus on spatial concerns about the jail, as those tend to be the only ones the city is willing to entertain.

0:17:50.8 Maya Singhal: This emphasis has sometimes come off as cold to people concerned about the human impacts the jail might have on people in the neighborhood and those incarcerated inside it. In February 2020, four months after the City Council approved the borough-based jail plan, NUBC and a handful of other petitioners, including the American Indian Community House, sued the city alleging that it had pushed through the jail plan without proper investigation of the adverse impacts of constructing the Chinatown Jail. Their lawsuit was successful at first, but was overturned on appeal. In 2022, artists, Kit-Yin Snyder and Richard Haas filed a lawsuit to stop the jail demolition under the Visual Artist’s Rights Act to preserve their artwork that is displayed on the Manhattan Detention Center building. This lawsuit too merely stalled demolition. So if you’ve never heard the term Mega-Jail before my talk, that might be because NUBC and their PR team coined it in 2019 to brand their opposition to the Chinatown Jail.

0:18:51.8 Maya Singhal: While they have portrayed the jail as a looming monstrous threat to the neighborhood, the city themselves have also enlisted the help of the Global Strategy Group to help garner support for the borough-based jails, highlighting formerly incarcerated people and their families who endorse the plan. Jan Lee, one of the NUBC founders, has speculated to me that he thinks the city is also offering formerly incarcerated people jobs in the new jails to encourage them to support the plan. While the fight foreign against the borough-based jails can often come off as very grassroots and local, I think it’s really important to note how many expensive PR and legal battles are going on behind the scenes to help shape public opinion.

0:19:33.3 Maya Singhal: In some ways, Stop Asian Hate Campaigns in response to anti-Asian violence since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic have also been a boon to the anti-jail coalition who have used the language of Asian hate to discuss the impacts of the Chinatown Jail. In fact, in April, 2021, during his campaign for Mayor, Eric Adams spoke at NUBC Press Conference opposing the jail. And you can see that in this picture on the left. “By placing a skyscraper of a correctional institution in this community, it’s only gonna continue to overshadow the voices of the everyday New Yorkers who are in this community,” he said. “I know this community, as a police officer, I was assigned to this community. I know how much they’ve endured, and so if you wanna stop the thoughtlessness that goes into what the community has experienced with the recent level of hate crimes, let’s stop the institutionalizing of the hate we’re seeing in government.

0:20:25.4 Maya Singhal: I join NUBC today in saying, no new jails, no building up a jail in this location. We can do a better job, and I know it’s possible to solve the problems we’re facing in incarceration without the destruction of communities.” Adams was elected Mayor of New York in November, 2021, and he still supports his predecessor’s plan to close Rikers and his office has said that it intends to follow the law and build the borough-based jails regardless of his former opposition to them. However, the decarceration parts of the jail plan have always sat at odds with Adam’s law and order politics. Adams has argued for re-instituting legal stop and frisk, the controversial NYPD Anti-Crime Unit and quality of life policing, which has often been called Broken Windows Policing. In the first six months of his administration, misdemeanor arrests for crimes like subway fair evasion and petty theft increased by 25%.

0:21:22.6 Maya Singhal: Since taking office, Adams has also rolled back to Blasio’s prison reforms, courting the DOC Guards Union, arguing for the use of solitary confinement and firing the DOC’s Deputy Commissioner for Intelligence and Investigation who had been working to process backlogged DOC use of force cases. By the beginning of 2023, Adams had started to talk about the increasing incarceration rates and a plan B for the jails that might keep Rikers open to address the dearth of beds in the planned neighborhood jails. As such, Adam’s adoption of the language of Asian hate highlights some of its limitations. A robust analysis of the structural racism that impacts working class Chinese populations might help to explain why Chinatown in the Lower East Side, which is historically a Latina neighborhood, have such a high volume of carceral institutions, homeless shelters, and drug treatment clinics. Instead, hate presents the issue of violence as an individual one.

0:22:20.8 Maya Singhal: People have prejudices that they enact on bodies they perceive to be Chinese. In the case of the jail, the language of hate highlights the individual policy decision to put a jail in Chinatown, rather than the structures of interrelated anti-Blackness and anti-Chinese racism that have created a carceral system that requires cheap land for constant updates and expansions because the promise of new and more ethical jails always seems to create institutions that are overcrowded, under-resourced and violent. The final strategy for fighting the mega-jail that I wanna discuss is protest. On April 7th, 2022, the city of New York announced that the Gramercy Group would be erecting fences around the Manhattan Detention Center on April 11th to prepare for demolition. The next day, NUBC put out a call for a protest at the jail at 7:00 AM, the morning of the 11th. On April 10th, NUBC posted on Instagram about the protest adding, “Remember to bring your ID.”

0:23:22.4 Maya Singhal: Descriptive warning was the only indication they gave before the action that the protest was not legal and that they were planning to get arrested blocking the Gramercy Group’s fences. When I arrived at the detention center for the protest, two minutes after 7:00, the speakers had already started and NUBC had set up a Black truck behind them on which they were projecting a video of the NUBC Press Conference at which Mayor Adams had called the construction of the jail institutionalizing hate when he was campaigning in 2021. People were handing out posters with Adam’s face and slogans like, “Hypocrites say one thing and do another. How can we trust you and you said no jail here?” Written in English and Chinese. Non-abolitionists, that is people without a systemic critique of policing, seemed to focus strongly on Adam’s hypocrisy. At another NUBC protest, Arline Parks, one of the most prominent opponents to the Bronx Jail said, “We, implying African American and Chinese people, had voted for Adams because he said he was not going to build the jail.”

0:24:22.8 Maya Singhal: Instead, she suggested that Adams had broken these campaign promises. But some of the abolitionist activists in Chinatown speculate that many people protesting the jail have a certain discomfort with the fact that Adams is a Black person in a position of power contributing to systemic violence against Asian people. “They don’t understand he’s a cop,” one activist told me. In other words, it might make sense that Adams might, for instance, frame the building of the jail’s institutionalized hate rather than as systemic racism. He doesn’t approach issues with a nuanced analysis of race and governance, he instead seems to see them as a lot of police officers do. Dismissive or unaware of how race shapes the way he treats individuals, he instead sees criminals and crime as the problem. Soon after I arrived at the NUBC protest, a woman came up to me with some information sheets entitled, ‘Know Your Rights’.

0:25:16.3 Maya Singhal: She explained that the protest was an act of civil disobedience. “If the cops ask us to disperse and we do not disperse, we could be arrested,” she told me. “Do you plan on being arrested today?” I said no and she walked away without giving me an information sheet. Actually, none of the protesters were arrested that day. The construction fences were not erected either. But after two days of protest, 10 activists, including the wife of former Presidential and New York Mayoral candidate, Andrew Yang, were arrested for civil disobedience as they blocked the Gramercy Group trucks. The activists were released later that day and their lawyer said that the court was unable to locate summonses for about half the arrested protesters. The other half were issued 24-hour adjournments in contemplation of dismissal, meaning if they weren’t arrested in the next 24 hours, the charges would be dropped and their case would be sealed.

0:26:07.3 Maya Singhal: Many abolitionist activists in Chinatown have been critical of what they see as the spectacle of these arrests. As a group of White people and prominent Chinese landlords and politicians, the protesters had little to lose from their arrests and little to fear from law enforcement. What did they intend to accomplish by getting arrested once? The construction fences went up around the jail, anyway. According to Jan Lee, one of the NUBC founders, the spectacle was the point. “We don’t think Eric Adams actually wants to build the jail,” he told me. “Furthermore, Adams appears to be gearing up for a presidential bid,” Jan explained. “He’s sensitive about his optics.” During the civil disobedience actions around the jail, NUBC drove the truck with the video of Adams saying, “Building the jail’s institutionalized hate around the city,” hoping to show Adams that they can publicly embarrass him. The arrests, Jan said, were meant to show Adams how serious they were, that their constituents would go to great lengths to stop the jail.

0:27:03.4 Maya Singhal: NUBC’s strategy was to get Adam’s attention, but stop short of alienating him from their cause. In short, they imagined their law breaking as illicit political strategy aimed at convincing Adams to work with them. As with the other strategies, the protest merely stalled jail demolition. NUBC’s more recent approach to the Chinatown Jail has been to try to work with the city to minimize its effects on the community. They have held information sessions to make residents aware of the concerns their architects and engineers have about the city’s building plans, and they’ve attended the city’s community meetings about design guidelines for the jail to try to ensure they have a seat at the design table. Meanwhile, another group called Youth Against Displacement has taken over protesting the city picketing outside of design meetings. They have also maintained a presence outside of the Museum of Chinese in America, which accepted money from the city as part of the city’s concessions to the neighborhoods in exchange for building the jail.

0:28:00.3 Maya Singhal: Youth Against Displacement argues that accepting these funds was an endorsement of the jail in the neighborhood., and they have been on the frontlines pushing a boycott of the museum, which has gone on ever since. Similarly, Youth Against Displacement argues that attending any of the city’s design meetings for the jail is acceptance of the jail’s construction. They worry that construction of the jail will be the death of Chinatown, although they have been less clear about their feelings about the other neighborhood jails. To some Black and Brown people from other parts of Manhattan, Chinatown’s opposition to the jail was racist. At the meeting about the jail’s design guidelines, I sat in front of two women from Harlem who had incarcerated family members and who vocally argued that Chinatown’s residents did not care about incarcerated people. To them, the choice of the jail site made sense because of its proximity to the courthouses.

0:28:47.8 Maya Singhal: However, more importantly, Rikers was so violent that it was as if the land itself were cursed. When Chinese people raised concerns that merely changing the jail site from Rikers to Chinatown without changing DOC leadership would simply export violence from the island to the new jail, the women insisted that these Chinese people did not understand the extent of violence on Rikers, it had to be closed immediately and the Chinatown Jail would inherently not experience the same levels of violence. The jail debate has thus created odd conflicts and coalitions. Although the government’s mismanagement of the jails is the cause of so much anti-Black racist violence, the government has positioned themselves as the saviors of these same populations through the promise of better jails. And many Black and Brown people desperate to see their loved ones in safer places than Rikers believe them. Meanwhile, Chinese people who for a range of reasons from leftist to conservative do not want a jail in Chinatown are allied with abolitionist activists who do not believe that constructing more jails can solve the violence of mass incarceration.

0:29:55.1 Maya Singhal: Chinese people stereotyped as a model minority with increased social mobility are easy targets for claims about anti-Blackness. And it’s true that some people in Chinatown are opposed to the jail for racist reasons. However, I find it puzzling to argue that Chinatown residents in their opposition to the jail are more racist than the government, which has yet to create a jail that could reasonably be called humane, and which targets Black and Brown people for incarceration while systemically defunding their neighborhoods. An effect of the model minority myth seems to be that Asian people’s prejudices are often treated as if they have more structural or systemic effects than they really do. Asians are often conscripted into White conservative projects like the fight against affirmative action or pushes for increased policing. However, I think the critiques I often hear of Asian people are outsized to Asian Americans actual political power, but White conservatives didn’t need Stop Asian Hate to push for more police funding, but because Asian concerns have so often been conscripted into conservative projects, I think we can forget that anti-Asian racism actually does have pernicious effects.

0:31:08.0 Maya Singhal: Asians were targeted for increased extralegal violence during the pandemic. For example, one of the questions I return to in my research is as we work towards building cross-racial solidarities, what are Chinese and Asian people more broadly allowed to ask for? Activists I work with often use phrases like we want a world where we can all be safe, but what does that really mean? What does safety look like on the ground in everyday life? And is there a way that Asian communities can ask for their neighborhoods to stay safer while we work towards safety for other Black and Brown people targeted for legal and extralegal violence? In other words, is there a way to take Asian concerns seriously while we work towards a better world for everyone? How would treating anti-Asian racism seriously in the context of other forms of racism changed the way we imagine our political coalitions and goals? To bring these questions back to the Chinatown jail, I wanna argue that taking seriously concerns about the spatial impacts of the jail on Chinese communities can help us to evaluate the limitations of promises of ethical jails in the anti-Black racism of mass incarceration reform.

0:32:16.2 Maya Singhal: It should prompt us to push for better futures than allegedly more ethical mega-jails, to instead imagine a world where we do not put people in cages and burden communities with housing these institutions. Thank you. And there’s my contact if anyone wants to reach out afterward.

0:32:32.5 Julian Agyeman: Thank you, Maya. That was an extremely interesting and informative talk. I knew a little bit about this, but I didn’t know as much as you’ve ventured. One piece missing Maya, your own personal positionality. What drives you to go into this is your PhD study, that’s a long time of studying. What is your motivation and could you say a little bit about your own positionality?

0:33:01.5 Maya Singhal: Yeah. I guess I stumbled upon prison abolitionists, like organizing. When I was in New York, I started working with a lot of students who were involved in various jail support and paying people’s bails and stuff like that. And then I did a master’s at the University of Chicago where I was working with a think tank in one of the prisons there that they were doing research because Illinois doesn’t have parole, so I was helping them complete some of the research that they wanted to do as part of that. So I think I got involved with all of these little jobs and people I met here and there. And then more recently, I’ve been working with this organization called Study and Struggle that provides a political education curriculum in and outside of prisons, mostly in Mississippi and Alabama. And I do a lot of their website and curriculum stuff.

0:33:53.3 Maya Singhal: So I think the question of abolition, the jails, is really important to me, but I think doing research in Chinatown also helped me to realize that you don’t need to be an abolitionist to see the problems of jails and that you can get people who don’t have those beliefs to get on board with really radical calls. People in Chinatown were chanting. They had Eric Adams, who is a police officer and absolutely believes incarceration saying things like no new jails. And it was a really interesting moment of bringing all these people in, and I would see people who started out just they didn’t want a jail in Chinatown and through the activism, they came to be abolitionists over the course of learning way more about how jails actually function. So I think for me, it was something that I was passionate about, but it was also really interesting to see how activists grow over time, and that was something that in my research really mattered to me to see we don’t come into this work completed. And so the jail fight has been a really fascinating site.

0:35:01.5 Julian Agyeman: Sure. Thank you. The racial politics of this are fascinating, aren’t they? Can you say a little bit more about that? There’s so many questions in my mind, the African American and Chinese group that formed the group and then the African American critics of this. Can you just say a little bit more about the racial politics, and then of course Mayor Adams himself who is a complicated character anyway. Yeah.

0:35:31.8 Maya Singhal: Yeah, it’s fascinating. So I think the one thing I didn’t mention about Neighbors United Below Canal is one of the founders, Chris Marte, who’s the City Council member now for that district, his brother, Coss Marte, was actually incarcerated both in The Tombs and also in Rikers, I think for drug trafficking charges. And he then founded this gym in Chinatown or in Lower East Side that does a body weight workout and all their trainers are formerly incarcerated because he found that body weight… When he was in prison, he was doing lots of body weight workouts and he was like, I’m gonna bring the prison workout. So it’s a little bit gimmicky, but it’s also this really interesting abolitionist space in a way because he brings these people in and if they don’t have a place to live when they get out of jail, he lets them house in the gym.

0:36:24.2 Maya Singhal: And then now actually, he was the first person to get a license to sell weed legally in New York City. So he has… The gym is called CONBODY and his weed distribution, his weed store is called CONBUD. So it’s just really fascinating like all these characters that are… And then Chris Marte also speaks Chinese for some reason, and all the Chinatown politicians have Chinese name. But it’s really interesting to have these Afro Dominican men who are so involved personally in this prison fight and working with the Chinatown community. So I think one of the things that I noticed ’cause people imagine Chinatown to be very just Chinese, and I think there’s a way to live in Chinatown and experience that, but I also think that there’s a way that Chinatown is actually much more complicated and diverse and has a really interesting relationship that’s building, especially with young people in the neighborhood that’s building these coalitions.

0:37:23.4 Maya Singhal: So that’s an interesting sort of side of the racial politics. And then there’s the way that I think because Eric Adams was a Black police officer, his campaign promises to not build these jails, which were… If you had a sort of critique of Eric Adams ever, I think it was really confusing why he would say he wouldn’t wanna build the jails ’cause if anyone wants to build the jails, it’s definitely Eric Adams. But I think the way that he was positioned, made him a more acceptable figure for a lot of the sort of more moderate Black and Chinese business owners and politicians, and that plays into the way that they imagine him. And then there’s all sorts of… I think Rikers Island is really scary. 30 people dying in the last two years is a really astonishing number for… And mostly pre-trial detention. So I think the other thing is, is I have a lot of sympathy for people who are like at any cost, get my friends and family off of Rikers Island. I think that when we’re talking about $8 billion of investments in more carceral institutions, there’s certain other financial questions that come into play. But I understand, I think the impetus at this point because Rikers is such a violent place. So across the board, it’s very complicated I think.

0:38:55.3 Julian Agyeman: It just occurred to me, and I’d never thought of this before, but as you’re speaking, there’s a principle in planning, transportation planning or planning for roads and this idea build them and they will come. You build more roads, more people come to fill the roads. Is that the same principle in carceral terms? You build more prisons… It seems to me you’re saying that pretty strongly, but build more prisons and you’re gonna fill them.

0:39:21.1 Maya Singhal: That’s the claim that Ruth Wilson Gilmore has always made. She’s always said that they build prisons at times that may or may not have any correlation to the crime rates. And then they always fill them to the point of overcrowding. And that’s the case with every single jail that has been at the site of the Manhattan Detention Center now, every Chinatown Jail has always been filled, far overcrowded.

0:39:46.8 Julian Agyeman: Okay. We got a question from Hugh Lester. You previously presented on this topic to an American Studies Conference. Maya, people are coming back to see you again. [chuckle] Was there a paper published in the proceedings or otherwise? Hugh apparently couldn’t find it.

0:40:04.3 Maya Singhal: No, there was not a paper for that. Although I think we might be doing an online version of that panel at some point. I’m not totally sure because American Studies this year was really Palestine-oriented, so that panel actually got pushed to an online thing later. So I guess stay tuned. Yeah.

0:40:24.2 Julian Agyeman: Okay. We got a question from Laurie Goldman who’s a lecturer here at Tufts. How have you seen the role of historical and anthropological research in shaping and organizing campaigns and coalition work, both mega-jail protests and abolitionist campaigns?

0:40:42.4 Maya Singhal: That’s a really good question. I think one of the things I was really interested in was one of the first things that NUBC did was go into the New York City archives and look for documents about this jail plan. And so they actually did find some things from, I think the late ’70s or something where people were suggesting that we needed to have smaller jails, but they meant smaller jails, like a hundred people in a jail as part of a rehabilitative space so that you could have things that are more incorporated into the community and that don’t have the kind of like large scale that allows for the kind of like DOC corruption we see today. So there’s this interesting move towards understanding… And people bring up like the Chinatown, like ’80s protests and things all the time because I think the way that people are working to convince the community that they can protest is by highlighting these older struggles and trying to understand where this jail plan comes from and how it’s been in their minds corrupted by different sort of forces in governments and in business.

0:41:52.3 Maya Singhal: That’s a really interesting non-professional historian angle. I think as an anthropologist, I’ve tried to be helpful in giving people working towards these issues a better sense of all the different kinds of people who have investments and what the investments are and like what you would need to do to convince people that you’re right. ‘Cause I think at the heart, I’m sort of an abolitionist and I want them to succeed. So as an activist and a scholar, I think my role is that I see a really big section of the community, and I think a lot of the people who are heading this, the people who have the money and can navigate the donations for these kinds of campaigns ’cause they are really big PR machines, they tend to be on the older side and they’re not necessarily talking to as many of the younger activists as I am. So I think as far as trying to be another, if not particularly expert, but at least having a different perspective voice in these, that’s the role that I see myself as an abolitionist and as a anthropologist.

0:43:09.8 Julian Agyeman: Thanks for that. So we have a question from Rahul Ramesh. How do you take the concerns of formerly incarcerated with the abolitionist activists? What do you say to formerly incarcerated folks when they’re in support of the jail? This seems like such a deeply personal issue for them. I guess also another part of my question is, how do activists square these dreams of abolition with the very real on the ground considerations of the formerly incarcerated and their families?

0:43:38.4 Maya Singhal: Yeah, that’s a really good question. I heard Ruth Wilson Gilmore speak a few… Maybe last year, and she said something about the jail plan specifically about this issue. And what she was saying is that as scholars, and especially when we’re like anthropologists or she’s a geographer, we can often just say that we want to just agree with what the communities we work in say, you wanna agree with people who are most affected by these issues. But we also do have expertise that they don’t always have. And we have sometimes a better sense of the long history of jail construction, even though they understand their lived experiences of the jails, but we might be able to contextualize it differently. And so we can’t always listen to them in that way. We can’t always just agree that their ideas are right because we have a different context.

0:44:32.6 Maya Singhal: And I think it’s important to say it is absolutely an essential goal to close Rikers. They’re right in that sense. It’s just that the history of building jails in New York and around the country suggests that building a jail is just going to create more incarceration. And so ultimately, even though it might hold the promise of more ethical world, we can’t always support that just because affected communities want us to because they might be missing some of those histories. And I think, I don’t know if that’s what you say to people because that’s hard to process, but I think as a political stance, there’s a way that we have to separate the fact that we want people who are incarcerated to have better conditions, but not at the expense of creating the conditions for far more incarceration. And probably also the same conditions in the long run because things don’t seem to get that much better with a lot of the… As the jails were constructed, the Manhattan Detention Center was supposed to be a more ethical jail at the time, and then The Tombs ended up being really dangerous, and yeah.

0:45:50.3 Julian Agyeman: Another question coming up from Hugh Lester. The land for Chung Pak was gifted to the city by the Chinatown community. This caused the North Tower to be taller than otherwise when it was designed. Would you care to comment on this? Is this something you…

0:46:08.7 Maya Singhal: I’m not sure.

0:46:11.2 Julian Agyeman: Hugh, are you able to put your question maybe in a slightly different format to Maya?

0:46:17.8 Hugh Lester: Sure. Okay. The land that the city owned at the time that they were considering building the North Tower of the Manhattan Detention Center, included the land that the Chuck Pecks Daycare Center currently sits on. That land was gifted to the community so that they could have a senior center. And that caused the North Tower of the Manhattan Detention Center to be taller. It otherwise would’ve been, but it was to give something back to the community so that they would accept the jail project. And I didn’t know if you were familiar with that history, but when they argued that the jail casts a long shadow and all that, the existing North Tower, speaking of that, no one ever mentions the fact that that senior exists because of that exchange.

0:47:15.6 Maya Singhal: That’s really interesting. I don’t know that I knew that, but I think this is also why people have spent a lot of time in the recent debates around the jail, talking about not accepting any concessions from the city because it is like a tacit acceptance of whatever the city decides to do as the exchange happens. So that’s why the Museum of Chinese in America I think is being boycotted so aggressively right now because… And being protested so seriously because they took a lot of money from the city. And I think by saying we’ll take whatever for our community, then the city has, it’s like giving them the sort of agreement to go ahead and do whatever they’re going to do, whether or not people would rather have it that way. So I think that’s part of the tricky kinda negotiations that are happening right now.

0:48:19.5 Julian Agyeman: Thanks. Final question. And it’s another one from Rahul Ramesh. I really appreciated your talk. Thank you. Do you know if these same racial dynamics or other community dynamics are present in the abolition fights across the country, like the Stop Cop City movement in Atlanta?

0:48:40.2 Maya Singhal: I have to say I… And maybe this is just because my relationship to Stop Cop City is through Study and Struggle and all of my comrades that are in the south and organizing against it. I actually don’t know a single person who is pro Cop City. So I can’t really tell you because the only thing I see is a pretty blanket. We would rather have a forest than a police training grounds. So I’m not really sure. I think it’s also complicated because it’s not clear that police training grounds have any benefit of any kind because increased police training doesn’t usually result in any actual improvement in the ways in which police are racist. So I think that it doesn’t quite have the same dynamics as the Rikers debate because the issue with Rikers is like, they’re kind of pros and cons both ways, which I don’t see in Cop City.

0:49:37.6 Julian Agyeman: Great. Maya, thanks so much for this. This has really opened my eyes. I’m dying to delve in and get some more information here. And Maya did put her new coordinates. Maya, would you accept emails if people have some questions?

0:49:53.3 Maya Singhal: Yeah, absolutely. Feel free to reach out.

0:49:56.2 Julian Agyeman: Thank you so much for that. Let’s give a great round of applause for Maya. Thank you.

0:50:01.4 Maya Singhal: Thank you so much for having me.

0:50:03.3 Tom Llewellyn: We hope you enjoyed this week’s presentation. Click the link in the show notes to access the video, transcript and graphic recording, or to register for free tickets to our upcoming lectures. Cities@Tufts is produced by the Department of Urban and Environmental Policy and Planning at Tufts University and Shareable with support from the Bar Foundation, Shareable donors and listeners like you. Lectures are moderated by Professor Julian Agyeman and organized in partnership with research assistants, Deandra Boyle and Muram Bacare. Light Without Dark By Cultivate Beats is our theme song. Paige Kelly is our co-producer, audio editor, and communications manager. Additional operations, funding and outreach support provided by Alison Huff, Bobby Jones, and Candice Spivey. Anke Dregnat illustrated the graph recording. And this series is co-produced and presented by me, Tom Llewellyn. Please hit subscribe, leave a rating or review wherever you get your podcasts, and share it with others so this knowledge can reach people outside of our collective bubbles. That’s it for this week’s show. Here’s a final thought.

0:51:04.7 Maya Singhal: As Ruth Wilson Gilmore has noted, there’s a long history of using overcrowding as an excuse to build more jails and prisons, which are quickly filled to the point of overcrowding. Increased jail and prison construction has historically preceded increased incarceration, rather than being a response to crime.

[music]