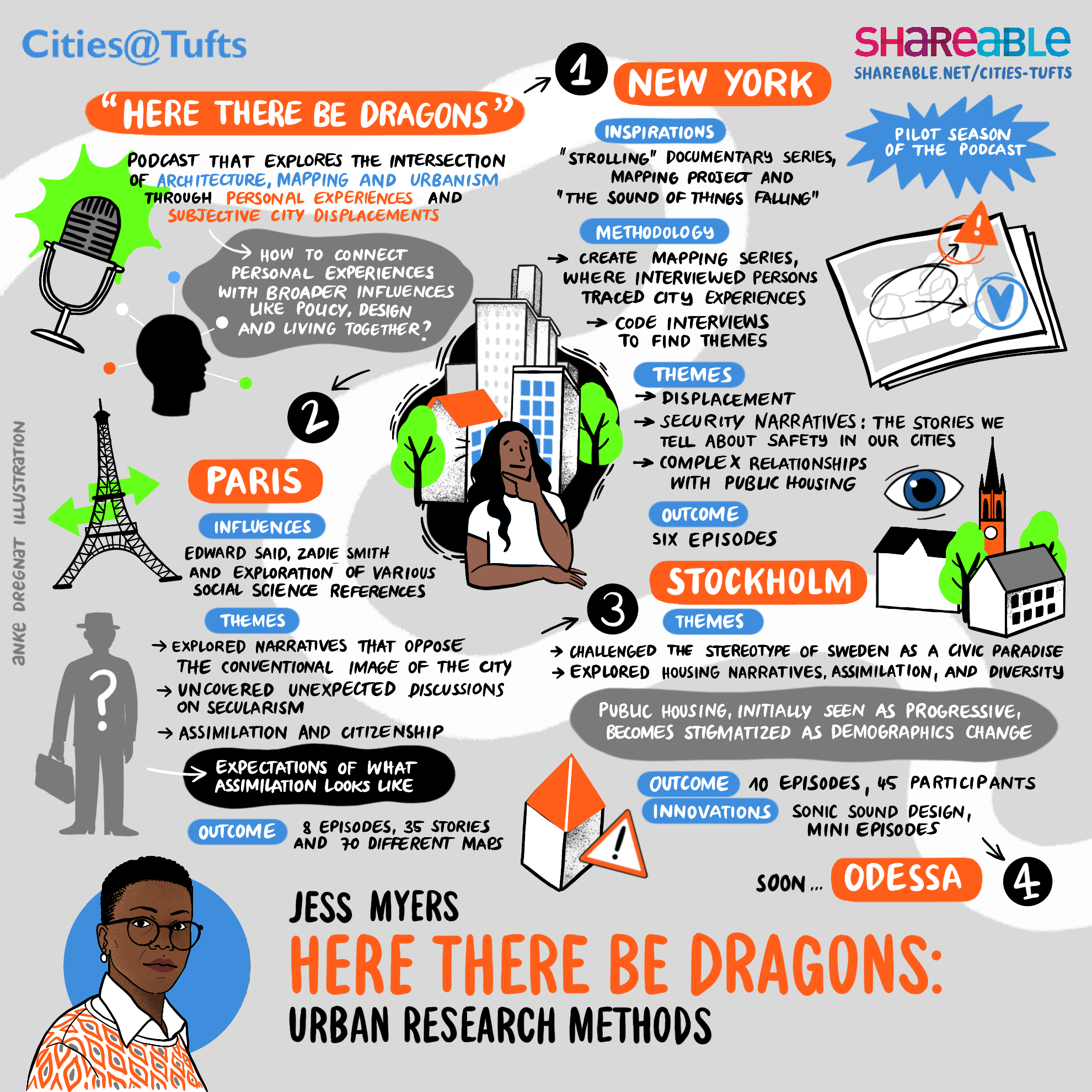

In this Cities@Tufts episode, Jess Myers discusses her eight years working on the research, design, and production of the urbanism podcast Here There Be Dragons. HTBD starts with residents first and seeks to forefront methods from the social sciences as crucial techniques in the analysis of the built environment. The podcast covers one city per season. Myers has sat down with residents in New York, Paris, and Stockholm to discuss what inspires their feelings of belonging and tension in their cities. Through these interviews HTBD traces a post occupancy study of urban policy, design decisions, and social attitudes.

Jess Myers is an urbanist and assistant professor of architecture at Syracuse University whose practice includes work as an editor, writer, podcaster, and curator. In the past, Jess has worked in diverse roles—archivist, analyst, teacher—within cultural practices that include Bernard Tschumi Architects, the Service Employees International Union, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, and Rhode Island School for Design.

Her research engages sound and multimedia platforms as a means to explore politics and residency in urban conditions.

Her podcast Here There Be Dragons takes an in-depth look at the impact of security narratives on urban planning through the eyes of city residents in New York, Paris, and Stockholm.

Her work can be found in Urban Omnibus, The Architect’s Newspaper, Log, l’Architecture d’Aujourd’hui, Avery Review, The Architectural Review, Places, Dwell, and the Funambulist Magazine. Her 2022 exhibition, A Pause Is Not A Break, was recently on “view” in Providence Rhode Island, Ames, Iowa, and Ottawa, Canada.

About the series

Shareable is partnering with Tufts University on this special series hosted by Professor Julian Agyeman (Co-chair of Shareable’s Board) and Cities@Tufts. Initially designed for Tufts students, faculty, and alumni, the colloquium has been opened up to the public with the support of Shareable and Barr Foundation.

Cities@Tufts Lectures explores the impact of urban planning on our communities and the opportunities to design for greater equity and justice.

Register to participate in future Cities@Tufts events here.

Listen to the Cities@Tufts Podcast (or on the app of your choice):

Here There Be Dragons Transcript

[music]

0:00:23.5 Jess Myers: By security narratives the stories that we tell about safety in our cities. And security narratives about New York are very powerful for me in my own life and in my own understanding of getting used to New York because they have such a political power. So essentially, if we say these neighborhoods are so dangerous and we don’t drill into but why and who is endangered and by what kind of violence or things like this, we begin to pathologize certain neighborhoods even though they have an enormous amount of meaning to the people who are living in them.

0:00:49.8 Tom Llewellyn: Welcome to another episode of Cities@Tufts Lectures, where we explore the impact of urban planning on our communities and the opportunities designed for greater equity and justice. This season is brought to you by Shareable and the Department of Urban and Environmental Policy and Planning at Tufts University, with support from the Barr Foundation. In addition to this podcast, the video, transcript, and graphic recordings are available on our website shareable.net. Just click the link in the show notes. And now, here’s the host of Cities@Tufts, Professor Julian Agyeman.

0:01:25.5 Julian Agyeman: Welcome to our first Cities@Tufts virtual colloquium of 2024. I’m Julian Agyeman, and together with my research assistants, Deandra Boyle and Muram Bacare, and our partners Shareable and the Barr Foundation, we organize Cities@Tufts as a leader in studies, urban planning, and sustainability issues. We’d like to acknowledge that Tufts University’s Medford campus is located on colonized Wampanoag and Massachusetts traditional territory. We’re delighted to host Jess Myers, who’s an urbanist and assistant professor of architecture at Syracuse University. Jess’ practice includes work as an editor, a writer, podcaster, and curator. In the past, Jess has worked in diverse roles, archivist, analyst, teacher, within cultural practices that include Bernard Tschumi Architects, the Service Employees International Union, MIT, and RISD.

0:02:23.5 Julian Agyeman: Her research engages sound and multimedia platforms as a means to explore politics and residency in urban conditions. Her podcast, ‘Here There Be Dragons’ takes an in-depth look at the impact of security narratives on urban planning through the eyes of city residents in New York, Paris, and Stockholm. Her work can be found in Urban Omnibus, The Architect’s Newspaper, Log, The Journal l’Architecture d’Aujourd’hui and the Avery Review. She had an exhibition in 2022, ‘A Pause Is Not A Break’, which was recently on view in Providence, Rhode Island, Ames, Iowa, and Ottawa, Canada. Jess, a Zoomtastic welcome to Cities@Tufts and over to you.

0:03:13.1 Jess Myers: Hello, thank you so much for having me. I am Zooming to you from Syracuse, which is the unceded territory of the Haudenosaunee and Onondaga Nation. So, today I’m going to be talking to you about the podcast, ‘Here There Be Dragons’, how it got started, what its sort of methodological underpinnings are, and what its progress has been over the course of three seasons and a little bit about what I’m working on with it now.

0:03:41.8 Jess Myers: So, I’m going to go ahead and share that. Also if anyone is being a timekeeper, really feel free to put a five minute warning or something like that in the chat because I sometimes can take these detours that take some time. So, I’ll share my screen. I like to call this conversation on being methodical. This was my studio, my desk that I had in Stockholm when I was doing the field research there. I like to use it as a backdrop ’cause it is the way that I work, just like a desk and speakers and headphones and people coming to talk to me in these often very strange corners of their cities. Often when we think about the intersection of architecture and that same mapping or urbanism, I think one of the strongest or perhaps first voices that come up in that regard are the situationists, are Guy Debord, who are speaking about a very sort of personal, the reave through the city, what we can understand on a subjective level of displacements through the city or what we can understand of an individual subject’s displacements in the city.

0:04:55.5 Jess Myers: And I think while that has definitely been influential, what was missing for me in my understanding of urbanism after my architecture education was really how do these things work together as a network? So, not just one or two subjective understandings of the city, but how do you connect those understandings to the city to the influence of policy, of design, and of living together really? So, I drew some other influences in my first year of working on the podcast, which was very much as a grad student, as a researcher at MIT. So, some things that came in that influenced me a lot were the filmmakers, Cecile Emeke, a young Black British filmmaker had been making this web series at the time, this was back in 2014, 2015, called ‘Strolling’. And essentially what she would do was follow Black residents, Black citizens of European cities around their cities as they talked about their relationship to various neighborhoods over time. And I thought that was an interesting way to understand and interconnect a different sort of perspective on the right to the city.

0:06:17.2 Jess Myers: I was also very in influenced by The Mapping Project, which is by a French Moroccan architect. Essentially interviewed folks who were trying to cross from Africa’s northern coast into Europe, essentially crossing the Mediterranean. And instead of doing all of these things of sensationalizing that effort, she simply gave each interviewee a marker and they just traced, this is where we met the smugglers, this is where we tried to cross. This is where we landed, where I was first deported, where I came back. So, you really get an understanding unattached to, let’s say, other ideological narratives of like why and how people make that journey. And then lastly, there is a novel by a Colombian novelist, Juan Gabriel Vasquez, called ‘The Sound of Things Falling’, that is about reestablishing a relationship with the city after an act of violence had happened there.

0:07:15.2 Jess Myers: How do you bring yourself to trust a city again? So from here, I worked on the, essentially pilot season for ‘Here There Be Dragons’. I had very crucially no idea what I was doing. I was using a program I didn’t understand, which was logic. I was just learning the methodologies of interviewing. I was also just learning the methodologies of field recording and very… Again, making a lot of rookie mistakes around recording people in empty echoing spaces, for example. But I learned a lot from doing this season. One of the methods that I developed in this season was creating two map series where every person that I interviewed would all trace what they were describing to me on these maps, where they outlined spaces where they felt alert or uncomfortable or in danger in red spaces of comfort in blue, and these sort of displacement that they made through the city in black.

0:08:22.0 Jess Myers: And then they would do that twice. So, we would see one from either their childhood or from the first moment that they moved to the city, and then the last from their current understandings of the city. So, this season yielded six episodes, and the way that these episodes came together was by using, again, a methods from the social sciences where I would transcribe and code each of the interviews that I had done. And in this season, the sample size was seven people. And essentially, instead of setting themes for the episodes in advance, I would code the transcripts, which meant looking for keywords or key concepts that were repeated over and over again in separate interviews. And then I would use the coding code language as the episode theme, and it allowed for these themes to flow a little bit more naturally. So, instead of pushing people to give their perspective on a certain thing, and to fit that into an episode season, to find what the natural resonance is between different interviewees.

0:09:36.4 Jess Myers: And for this season, what was interesting to me was it was focused on a city that I grew up next to. I’m from New Jersey. There’s just so much mythology about New York. And again, the thing that drew me to even start this season was in thinking about questions of security narratives and by security narratives and stories that we tell about safety in our cities and security narratives about New York were very powerful for me in my own life and in my own understanding of getting used to New York because they have such a political power. So, essentially if we say, these neighborhoods are so dangerous and we don’t drill into, but why and who is endangered and by what kind of violence or things like this, we begin to pathologize certain neighborhoods even though they have an enormous amount of meaning to the people who are living in them.

0:10:33.8 Jess Myers: So, these are the themes that emerged from the first season. And from this experience, I went on to turn this project into my thesis project for at MIT and it… I’m getting ahead of myself. I just wanted to play also a little clip from this season. And again, one of the things that came up over and over again was public housing. And I think that in this way, often in the news you hear public housing talked about only as a problem. And in the interviews what came up was a little bit more complicated was what are people’s relationships to public housing from living in them, to living by them, to being told different narratives about them. So, that came up over and over again naturally in the interviews. So, I’m just gonna play a clip from that episode, from the public housing episode.

0:11:30.4 Jess Myers: How does the reputation of public housing change when your family lives there, when your family’s history is tied up in this piece of New York history?

0:11:39.8 Speaker 4: I think the projects to my family just represent a time period. Like I still have family in the projects very much. And I think it’s like a gift and a curse, like a lot of things went down on the projects, which you also had some really great times in the projects as well. Just inside of that space. It is like, I could never talk down on the projects by any means because not to say but I grew up there, you know what I’m saying? I went to my family’s houses and I lived in buildings my entire life. So, I over-stand what it’s like to live in the projects and/or project buildings.

0:12:16.6 Jess Myers: And from there, again, like I said, I developed this into what became my thesis project or my thesis submission for masters in city planning at MIT. So, the next season I focused in on Paris and began taking in a broader range of influences in terms of building narratives or perspectives, essentially what you might call, how do you build a narrative out of even opposing understandings of the exact same space. So, definitely looking at Sayeed and looking at Zadie Smith’s writing were really helpful in developing season two, but also really digging down into different reference points from the social sciences.

0:13:02.5 Jess Myers: And also, when I was much younger, I did go to a social sciences school in Paris and worked with one of the Fassin brothers or took a class from one of the Fassin brothers. And it led me down this path of like really drilling into different social sciences references for the city that peel back this understanding of Paris as this sort of picturesque city or even the city, Paris is a city that wants to demonstrate itself as a very progressive environment, but really drill down into what residents themselves were experiencing based on different policy regimes, design regimes, and urban planning regimes that had passed through the city.

0:13:42.5 Jess Myers: I had also began taking a course with the artist Renée Green, who is a writer and a filmmaker in her own right, but we were watching essentially essay films. The class was really focused in on essay films. And one film that had really influenced me, it was a film by the Vietnamese American filmmaker, Trinh T. Minh-ha who made a film called ‘Shoot for the Contents’. And I’m not gonna go into explaining too much about it. Besides the way that it approaches translation is very interesting. She stages every act of translation as a conversation between a speaker, a translator, and a listener.

0:14:24.5 Jess Myers: So, I wanted to take that on too as being attentive to the way that in a, you develop a sonic relationship to translation, which is still something that we try to push in in the podcast. And then also I met my producer, Adélie Pojzman-Pontay who is quite an experienced radio journalist and helped shape more standard practices in radio making that made the podcast again sound much more professional and brought her, I think really establish season one as being very much the pilot and season two as being something where I was stepping more effectively into tools of radio making. So here we had 35, a sample of about 35 different interviews, different stories. So, that was I guess, 70 different maps and eight different episodes this time. So again, this season is really emerging naturally from the coding of the interviews because I did the field research for this season right after the kosher market shootings and the shootings that happened in the Place de la République region and the Grande Stade de France.

0:15:44.8 Jess Myers: What I was expecting from the pre-research that I had done and from the news that was coming out at the time was that people would really want to talk about things like policing. They would wanna talk about violence, they would want to talk about maybe immigration. But really what struck me was how much people wanted to talk about secularism. And this is something that I very much learned and I’m grateful to in the method of the podcast, is that it gives you enough space to push aside preconceived notions of what you think the focus of the work is going to be and more nimbly move forward with what is actually being discussed in the interviews. And again, so what people were discussing in terms of in relation to their safety in public spaces was thinking about how, because France has such a both rigid and deeply confusing understanding of secularism, that people were very much paranoid about how do I represent myself in public space in an extremely secular way. But at the same time, were being questioning of whose secularism matters most. Who gets to display that they are a part of religious community and who doesn’t. And the clip that I have from is from the community episode and is very much grappling with that idea of who gets to make these public displays claiming their participation in certain religious communities in Paris and Paris’s public environments.

0:17:28.2 Jess Myers: In previous episodes we talked about communities and minorities in France, we’ve also mentioned how some communities are allowed to exist and be visible while others are not. Frank also explained how the nationwide debate about same-sex marriage showcased the double standard that exists between communities. This led him to question his own community.

[foreign language]

0:17:53.1 Speaker 5: I have a lot of doubts about my own religion, especially with the demonstrations against same sex marriage. I thought it was very aggressive of French Catholics to demonstrate their religion like that. It didn’t go over well with me at all. I thought it was extremely violent. I don’t think that they realized the violence that it can instigate the target that they put on their backs. They feel totally protected. And I think that if Jews or Muslims demonstrated like that, there would’ve been very violent reactions against them physically violent.

0:18:24.0 Jess Myers: So again, in this moment, other researchers, because of the, because of so many interviews independently bringing this up, we brought in other researchers like Mayanthi Fernando or Mehammed Amadeus Mack, who were talking about practices of secularism. And again, this expectation in this period of moving beyond a melting pot idea of multiculturalism and being even more, having even more expectations of what assimilation looks like for immigrants in this country and also even the question of immigrants in France is quite complicated because one, after World War II, “Immigration from the colonial holdings at the time was very heavily recruited in order to rebuild after World War II”. And also in that period, if you were under, let’s say the colonial regime of France, technically you had a French citizenship. So, in the moments after independence, it was when this narrative of actually the people living here are not French, they are some floating immigrant status that that never leaves, which means that you constantly have to prove your assimilated status in public space even when you are like a third, fourth generation Parisian. So, what kept coming up over and over again is the moving goalpost of what an assimilated person looks like.

0:19:58.0 Jess Myers: And one of the things that comes up very much in Mehammed Amadeus Mack’s work is that the immigrant body in public space is expected to have even more progressive ideals than the host country to prove that they are assimilating civically into this host city or host country in question. So, that was something that I found and learned a lot from in doing the Paris season. So, moving on from after graduating, I thought that the podcast was over because I wasn’t sure how to fund it. I wasn’t sure how to move it forward, so it fell into a long period of silence until I ended up going to a brief residency program at the Canadian Center for Architecture and met a Swedish architect and journalist there who asked if I might be interested in doing a program in Stockholm and potentially a season on Stockholm, which ended up working out, and again, built in a new set of pre-research focusing on this stereotype that we have about again, Scandinavia in general and Sweden in particular, as this civic paradise in a way where everything goes really well and everyone gets… The social safety net is strong and there’s much more civic cohesion and things like this.

0:21:26.5 Jess Myers: But the reason for why that cohesion existed was, is very much security narrative in itself, especially in North America. And a narrative that was being pushed at the time, so this would’ve been 2018, 2019, was that the reason why these spaces were able to have ‘civic cohesion’ was because of their homogenous nature. But at the same time, the fact that Sweden had been one of the most open asylum and refugee programs in the world, in especially the ’60s and ’70s, early ’80s, was that you did see a lot of different types of diversity in Stockholm that you would not see in other cities. So you have Chileans, former Yugoslavians, Lebanese people from the Levant region in general, Sudanese, Ethiopian, all mingling within this space and because of the housing program that was developed in Sweden at the time, folks from all of these different spaces living in public housing, so in fact, this public housing, and also public housing in Sweden is housing that is for the public, it’s not quantified for any specific socioeconomic class.

0:22:50.1 Jess Myers: But yeah, so you would see folks who were living in these communities together and actually much more diverse than let’s say the city center that was what? I guess the political designation is ethnically White Swedes. So I also, for the Stockholm season, met someone that I have been collaborating with very closely since 2020, Adrian Lilly, who’s a phenomenal sound artist in her own right, and also an extremely precise and talented sound designer. So again, the sound of the podcast begins to change and we start interrogating sound as an aspect of the research and how do you use sound again to trigger some of these moods and atmospheres that are being discussed in the interviews. I also started working with a really fantastic group of students at… It was the first time I was able to bring student workers into the podcast, which was also, just was a huge lift. And they were able to do things like ensure that we had transcripts on the website so we could just widen who was able to experience and listen to the podcast.

0:24:00.5 Jess Myers: So, here we had a sample size of 45, and we were able to use new interview techniques in this season, like being able to talk to young people, folks from the age of 12 to 18, which was fantastic. We, in this season we’re also able to change up interview strategies and interview people as pairs or in groups, which was also really interesting and added more texture I think to the interviews as well. But again, kept the same methodology of setting the themes of each episode based on the coating of those interviews afterwards. So, this season produced 10 episodes, our first double feature, which was on the idea, so in the season on Stockholm, what came up so often was the specter of housing. The interesting thing about these housing programs in Sweden is that they also, similar to housing in the US or in France, went through these periods of, when they first get built they are symbols of progress and of the future.

0:25:19.6 Jess Myers: But as they gain, let’s say, new tenancy of not just working class Swedes, or not just ethnically White Swedes, but also new immigrant Swedes, there concurrently builds this security narrative around housing that there’s something dangerous or unassimilatable about the housing projects, even though they are very Swedish [laughter] that they were a Swedish policy very much conceptualized within the framework of Democratic socialism, which is the, or had been the, I think party in power for maybe 70 years from the 1920s, 1930s to, I want to say their coalition began to break down in the ’90s, early 2000s. So again, getting into this idea of, what do people mean when they’re talking about segregation or what are people talking about when they mean housing insecurity and really digging into those ideas. The clip that I’m about to play you is from that season, it’s from episode three about, again the challenges of moving, because you can still get a lease in these, what are called Million Programme housing, these public housing. However, it can take, the wait time for an apartment can take up to 20 now 30, 35 years. So, I’m just going to play that clip quickly.

0:26:54.5 Jess Myers: Waiting time. When you get to the front of the line, you win the jackpot, a lease you can hold for the rest of your life. But waiting can literally take a lifetime, 20 years or even longer.

0:27:10.5 Speaker 6: I might be dead by the time my name comes up, maybe.

0:27:11.4 Jess Myers: These lines can get so long that Stockholmers used to put their children on the housing queue as soon as they were born. Although, now the rule is you have to be at least 18 to be on the line.

0:27:21.4 Speaker 7: I started to live in Vaxholm.

0:27:22.6 Speaker 8: And we put church kids in that line.

0:27:25.3 Speaker 7: And I lived in Solna.

0:27:27.7 Speaker 8: When they were born.

0:27:28.5 Speaker 7: I lived in Stureby. That was like six years when I was first put in this queue out in Jakobsberg.

0:27:36.0 Speaker 8: And if you are put in that line, you will get that apartment by your 30. [laughter]

0:27:39.1 Speaker 7: A White contract.

0:27:40.9 Speaker 8: I’m not sure you can do that anymore. Put babies in the line.

0:27:44.7 Speaker 7: I found a place in Björkhagen.

0:27:48.9 Jess Myers: But again as you can probably hear with bringing Adrian in as a collaborator, one of the things that we really drilled down to talk about is what is the sonic character of the podcast meant to be and how can that again, lift the research? And something that we focused on was this image of imagining a crowded public square and me as the host guiding someone through a crowded public square where they could overhear conversations about the city that might interact with their own concerns about their own cities.

0:28:24.7 Jess Myers: And an image that I really like from Adrian is the idea of holding… When are you holding your listener by the hand? Very didactically laying out information and then letting that hand go and allowing them to have almost a sense of exploration through the sound design, which is something that we continue to work on. Another aspect of that comes through in how we work on translations, because there were so many English speakers in this particular season, we only had a couple of folks who wanted to speak in Swedish or wanted to speak… Actually, we had a couple of folks who wanted to speak in Spanish because again, as I said, there’s a very significant Latin American community in Stockholm. We played with different ways of designing that translation, that active translation in the sonically. So, in some instances when we are doing a sound collage, which is juxtaposing many people’s answers, like you just heard, we would leave Swedish speakers untranslated. So, it would sound…

0:29:29.4 Jess Myers: If you were not a Swedish speaker, it would sound as if the next person after who was speaking after the spoken Swedish was translating that Swedish. But if, and you would get the same idea as if you were a Swedish speaker and you understood the Swedish as well as the English, then it would sound like a conversation between those two voices. Or in another instance where we were translating a Spanish speaker, we put the English speaker in one ear of the headphones, we panned it to the right and then we put the Spanish speaker in the left headphone to again, make it sound as if two people are talking on either side of you. And one is translating for the other. Because the thing that we tried to grapple with was the idea of the English translation is trampling the original speaker as opposed to working with them or in conversation with them.

0:30:25.0 Jess Myers: And we thought about ways of, how do you bring that out in a sonic quality? So, another thing we were able to do in the Swedish season, and then I think after this I will conclude, is there are moments that happen in the interviews that are interesting discussions that don’t quite align with any of the coding in the interviews. And it’s a shame to not spotlight those moments, like a very interesting story or a very particular expertise. So, we created these very short minis, I forget 10 episodes of minis where we just focused in on maybe one or two people speaking. But for the most part, just one story of someone’s expertise. So, we spoke to someone who was a fashion designer and she talked about how the clothes and the idea of assimilation play out in public space in Stockholm, or we talked to someone who was an investigative journalist in the ’90s, was focused on the rise of skinheads. Skinhead culture in the center of the city. And we did an episode spotlighting him. We spoke to two curators, who were the first black curators of the ethnographic museum in Stockholm.

0:31:58.9 Jess Myers: And they were talking about how the museum was pushing the repatriation conversation in the museum system in Sweden. So, we did a spotlight on that. And then one of the, my favorite [laughter], is we talked to a urban marine biologist who really focused on non-human traffic moving through the city of Stockholm. And his particularity was fish traffic, because Stockholm is a city that’s in the middle that is on this dividing line between a freshwater lake and the Baltic sea, so that makes it a very ecologically diverse city as well. So, it was interesting for him to spotlight this idea of how do you also design cities for non-human movement? So, we did a spotlight on that as well. And I think for me, the work on the podcast has been practice and one, how do you think about public presentation of research in a different way? And also, how can the medium of sound be something that highlights and picks up aspects of the research that might not be captured in, let’s say, a journal article?

0:33:14.6 Jess Myers: It’s… I’ve learned a lot from this methodology, essentially. I’m currently working on season four, which was focused on Odesa, Ukraine, which was the city that we chose before the current invasion. But in this moment, we decided to continue to work on it and at the same time, switch up our methodologies in a way where we could continue to pursue the interviewing, and also include people who are diaspora from Odesa. So, interviewing folks who are displaced from the city as well, which is the first time we’ve done that. So, I’ll be curious to see how the field research for this current season builds into a cohesive understanding, or maybe in-cohesive understanding of Odesa, but that’s the process that I’m in right now.

0:34:25.2 Julian Agyeman: Great. Thanks so much, Jess. That was a really interesting presentation. Mediator prerogative. I got a few questions ’cause you and I spoke before, you and I both spent time in Stockholm and I think Stockholm comes as a bit of a shock to a lot of Americans who think, and Brits, who think Sweden is full of tall blonde haired people. And in a lot of parts it is, but Stockholm, as you rightly say, is incredibly diverse. In fact, a lot of the Scandinavian cities like Copenhagen, Oslo, Helsinki are very diverse, reflecting, again, as you’ve said, the long social welfarist, social democratic traditions of these countries.

0:35:17.1 Julian Agyeman: But you use one word in relation to Paris, and I think it’s a very accurate word, assimilation. I’ve noticed that the Swedes and the Danes use the word integration. We don’t use these words so much, do we anymore? When you talk of assimilation and integration, that seems more like America in the ’60s. Can you say a little bit about that? Because it seems that these issues are to the fore with a lot of the people that you spoke to.

0:35:49.6 Jess Myers: Yes. I also think that these issues are driving politics in a major way across Europe and North America. And I think that what we’re seeing is a lot of, let’s say, ideological regime changes in what it means to live in a, let’s say, multicultural society, which again, you might find to be a dated word. The idea of multiculturalism may be more tied to the UK in the ’90s, for example. I find that it is imperative to talk about, especially if you’re ever talking about safety or security, the expectations of, let’s say, living in a ‘host country’, and these moving goal posts of what it means to be successfully civically integrated.

0:36:42.1 Jess Myers: This is something in this research, especially for France, I have to say, I relied heavily on the writing and thinking of folks like Eric and Didier Fassin, of Maurice Blanc, Sylvie Tissot, and of Mehammed Amadeus Mack and Mayanthi Fernando, who I mentioned, because they’re all talking about this idea of changing expectations and manipulations of narrative around integration that have been pushing politics. So, even in the language of there is a European immigration crisis, what does that, or even in the United States, the idea of a ‘migrant crisis’, what does that mean?

0:37:31.8 Jess Myers: And who does it say is in crisis? And this is also a temporal question because you are pitting the very real and present danger that many folks who are attempting to immigrate whether within the “Legal means” or outside of it are actively fleeing from conflict zones actively fleeing from often famine often fleeing from different types of let’s say extra-legal violence fleeing from state violence as well. So, we’re pitting that against the possibility of perversion that the Americas or Europe might face should they take on quite frankly their international responsibility of accepting refugees and asylum seekers.

0:38:32.5 Julian Agyeman: Just going a little bit further with that. So, two things became very immediate and obvious to me. One so one of the immigrant neighborhoods on the outskirts of Stockholm is called Tensta. You might have gone to Tensta and I went there and you get on these beautiful subway cars and it’s not a horrible looking flanky 1969 screeches when it goes around the corner coming into Harvard. This is beautiful new railways. You get out to Tensta which is the suburb and it’s ’60s ’70s Swedish housing and it’s nice. The neighborhood is full of trees and bike paths and the housing stock is very good quality. So, the immigrants were obviously put in not in an immigrant neighborhood but in a Swedish neighborhood that was built for what you said “White indigenous Swedes”. And I got talking to the Somalis and some of the immigrants there and they said,”Yeah. We’ve got no gripe about where we live and the conditions. It’s just we’re excluded from Swedish society.” So, that was one thing that I noticed.

0:39:50.4 Julian Agyeman: And then the second one of the reasons that I have connections in Stockholm is that I was an examiner on a PhD fascinating PhD where Dr. Karin Bradley at KTH. She was looking at how do immigrants to Sweden become Swedish. She found that a very strong narrative was the Swedish nature and sustainability narrative. Swedes they like going to their homes in the mountains. They like sustainability. And she said some of the immigrants really hold on to this and they developed Swedish like lifestyles to become Swedish. But she said there was a lot of pushback from some immigrants. They were saying you’re talking about sustainability. You’ve got two cars. You go on two foreign holidays a year. You’ve got a home here in Stockholm and up in the mountains. In what way are you sustainable and don’t talk to us about sustainability. We exist on meager means. And so, I thought these two things were really interesting how to become a national of a country. You almost have to take on the national narrative unchanged. And I think that fits very much… And I’m going to give you a link to Karin Bradley because I think you and Karin could have some very interesting conversations. But anyway so it’s just a point and how the experiences of Swedish immigrants to Sweden, immigrants to France and immigrants to the US how they have very different sort of trajectories expectations et cetera. So yeah.

0:41:33.0 Jess Myers: I definitely agree. Yeah I love Tensta. I think it’s a fabulous place. Also something that is under… It’s I think the Million Programme in general is under-discussed in the US. But I will also say that the tenants organizing that happens is also under-discussed. So, something that’s really wonderful about Tensta too and about a number of other Million Programme housing developments is I think in the late ’70s early ’80s they organized towards this quite successful gallery space. But then rather than just using it as a whatever Tensta Konsthall like regular gallery space they also use it as organizing space for tenants as well. And they use it for language learning classes. They use it for questions about the immigration paperwork. They use it about organizing towards repairs things like that. So, I found that aspect of folks living there to be quite strong. And this idea of organizing towards those resources that you’re seeing yourself shut out of was an aspect of the way that people understood their own safety.

0:42:50.3 Julian Agyeman: But one little challenge I want to put to you…

0:42:51.1 Jess Myers: Please tell me.

0:42:53.0 Julian Agyeman: Well, a challenge I think it would be a great podcast. I was talking to some of the Somali guys in Tensta and I said “You live actually in a very nice place. If we were to bring some Somali refugees from Boston to Tensta they would walk around and say wow, you guys made it big. You got it good here. Looking at the physical environment.” And so I think it would be good to bring groups of immigrants together from different cities and just see how their daily social spatial practices are et cetera. Anyway we can sort of…

0:43:25.6 Jess Myers: Okay, wait. This is a fabulous thing because it already exists in like different kernels in Stockholm. So, there’s this one organization called the…

[foreign language]

0:43:30.7 Jess Myers: Which the quote-unquote… Many of the Million Programme neighborhoods are called the suburbs even if they are like within Stockholm. And…

[foreign language]

0:43:35.6 Jess Myers: Is a city to rural solidarities organization. So, talking to folks who are placed in whether they’re in a city context or rural context and then they build that out to other countries with similar conditions of like city and rural quite close to each other. And then there’s another program that is more of a food program. I’m forgetting the name but I’m remembering. I am forgetting this woman’s last name. Her first name is Sarahswati. She’s very interesting. She does a lot of urban farming work which is interesting in Stockholm because a lot of refugees and people who are refugees in the ’70s and asylum seekers in the ’70s were also farmers or agricultural workers. So there are these spaces like one that’s called Husby Gourd where folks come together and talk to each other about different farming techniques that they used in their own context and then also connecting that out to other cities in the region who have similar context. But yes I think this is just… It’s a fabulous idea.

0:44:58.9 Jess Myers: But okay let me jump into these questions. So, for the question from John about the maps. This is a very good question. It’s driven me a bit crazy. The primary use of the map is really as a tool to get people to talk and to talk in a precise way ’cause often when we’re describing our cities we can be a little bit vague and I noticed that early on. So, I thought okay if you put this base map in front of folks and they have to draw and then describe what they’re drawing they will help which produces like an interesting artifact but it’s not necessarily a research instrument I would say. We use them it’s almost as if they stand in as avatars for the people themselves. So, we never put up images of our interviewees for example like this was again the whole point of one of the main points of using audio.

0:45:50.7 Jess Myers: So, again what they play and especially I have to say in the Stockholm season they were pretty vital because folks needed to be drawn out and the maps were a way of drawing people out. And it has also become a challenge because in the Odesa interviews that I’ve done so far I’m not sitting with people we’re often talking over Zoom which presents its own challenges both in terms of field recording and also in terms of just the active interviewing. So, we’ve tried different strategies around how do you bring that mapping component or help draw people out into that precise descriptive language way. But I don’t think that we’ve been managed it quite yet. References and methods looking at the policies in Stockholm. Oh yeah. There are so many fabulous researchers as I mentioned in Stockholm. I’ll give you a few names.

0:46:51.3 Jess Myers: One is Jennifer Mack fantastic researcher and writer. Another is Erik Stenberg who’s at KTH and really focuses in on the Million Programme. He has an essay and a book called ‘Small Interventions’ that’s quite good. There’s a research and architecture office called Secretary Office that focuses in on how new development in Stockholm has been such a stark difference from the ideals of a Million Programme and is often being built with building technologies that are actually much worse. Whereas the Million Programme housing is pretty solid even after I think what we ended in the ’70s so they should be many of them 60-70 years old. So, those are prefabricated concrete panel constructions. And there’s new construction methodologies that are coming although they’re being advertised as being much greener are often have much shorter lifespans. They’ll likely have to be rebuilt in 15 to 20 years.

0:48:06.8 Jess Myers: How have your interviewing techniques changed over time? What a good question. I think I’m much more comfortable moving into the follow-up question territory. I think especially when you start out and IRB is so terrifying [laughter] you’re like okay I can only ask these specific questions and this is something that I’m still developing is how do you chase down the specificities of an individual’s experiences? And I think the more that you’re able to do that actually that you have more runway for connecting it to other interviews, you’re giving them spaces where they’re really driving into what they are the most familiar with. And then you actually find language that comes up over and over again. Like for example even been in the Odesa interviews that I’ve done so far the use of the term Soviet. So, if folks were born before Ukrainian independence in ’91 they’re not identifying themselves as Russians.

0:49:06.3 Jess Myers: They’re identifying themselves as having been a part of the USSR which is a huge distinction. And also it’s a different understanding of sovereignty as well. I’m actually gonna jump to Louise’s ’cause there were two in that regard this idea of sound and the design element of sound. Yeah. That does a lot actually to the point where right now or in between seasons I’ve been doing a lot of research just drilling into sound. And that was a part of the presentation that I was like okay I’ll hold off on this part because it will take us on quite a lengthy detour. But for me I’ve been looking at researchers like Nina Sun Eidsheim or Jennifer Stover who are thinking of the politics of listening and how you play with the acculturation of people’s ears. For example I’m sure many of the people who listen to the podcast do not know that I’m a Black person.

0:50:05.6 Jess Myers: And I think there’s an assumption there is this kind of sheen over the radio voice or over the podcasting voice that it is this middle class like White space. And in the sound you can play with that you can play with the announcement of actually I look like this in order to make a point and an argument about the research which is something that I did in the segregation episode of the Stockholm season. Again which creates a kind of a moment. It at times can create this moment of dissidence in your listeners. And when I say acculturation what I mean is that there are depending on how you grew up the environments you grew up you have habits of listening. And I think the interesting thing about ears is as many other people have also said there’s no ear-lid, right?

0:51:05.4 Jess Myers: The idea is that your brain is always taking in sound and then reprioritizing it for you, right? So, you’re actually taking in a lot of information and then your brain is actively de-prioritizing a ton of it. So, by acculturation it’s this question of what has your brain learned how to prioritize and deprioritize? What are you used to focusing on? What kind of sound are you used to focusing on? And what kind of sound are you used to de-prioritizing? So, that’s again something that we play around with in the sound design. It’s borrowing a technique from this radio producer and concert pianist Canadian from who was doing this work in the ’70s ’60s late ’60s ’70s named Glenn Gould who has a very famous work called The Solitude Trilogy which is really about the Canadian imaginary of the north of the Arctic of the Canadian “what is now Canada of the Arctic”.

0:52:05.3 Jess Myers: And he invents this technique called ‘Counter Punctual Radio’. And if you are a musician you might know that the counter punctual is like multiple voices singing or speaking or acting at once. And the idea is that the different acculturation of ear will pick out different voices from that chorus, will focus in on different voices from that chorus. And what you hear is based on the acculturation that you brought in. And the interesting thing about that too is that then when you listen again and again you slowly pick up different voices within that chorus. So, it creates this re-listening possibility.

0:52:41.5 Julian Agyeman: Can we all give her a virtual hug to Jess Myers from Syracuse University. Jess fantastic.

0:52:49.2 Jess Myers: Thank you so much for having me. I really appreciate it.

0:52:53.2 Julian Agyeman: Yeah.

0:52:55.2 Tom Llewellyn: We hope you enjoyed this week’s presentation. Click the link in the show notes to access the video transcript and graphic recording or to register for free tickets to our upcoming lectures. Cities@Tufts is produced by the Department of Urban Environmental Policy and Planning at Tufts University and Shareable with support from the Barr Foundation Shareable donors and listeners like you. Lectures are moderated by Professor Julian Agyeman and organized in partnership with research assistants Deandra Boyle and Muram Bacare. Light Without Dark By Cultivate Beats is our theme song. Paige Kelly is our co-producer, audio editor and communications manager. Additional operations funding and outreach support provided by Alison Huff, Bobby Jones and Candice Spivey. Anke Dregnat illustrated the graphic recording. And this series is co-produced and presented by me Tom Llewellyn. Please hit subscribe, leave a rating or review wherever you get your podcasts and share it with others so this knowledge can reach people outside of our collective bubbles. That’s it for this week’s show. Here’s a final thought.

0:53:54.8 Jess Myers: Instead of setting themes for the episodes in advance I would code the transcripts and then I would use the code language as the episode theme and it allowed for these themes to flow a little bit more naturally.

[music]