For over 15 years, Jesse Richards has run a successful blog sharing his views on everything from Tolstoy to comic books to artists such as Whistler. It has become a montage of his diverse passions and fusion of his thinking about our future. Jesse is also the author of the book The Secret Peace: Exposing the Positive Trend of World Events and a former product manager with community self-organizing platform Meetup. “Bad news is easy to see; it jumps out at you," says Jesse. "Positive trends are often slow and less dramatic. It takes extra work to see them, and to report them in an interesting way.” In this interview, he explains the forces pushing society towards peace.

Rachel Botsman: Please, can you briefly describe your background and what inspired you to write on this particular subject?

Jessie Richards: I grew up with parents who taught me about human rights and participated in a wide range of community service projects. I was continually hearing about equality and peace. I studied Gandhi's work a lot, too. As an adult, I also became interested in critical thinking as a topic, especially after reading Carl Sagan's The Demon-Haunted World a decade ago, and that led me into examining media bias. In putting the two things together, I began to see that trends and clues of progress toward world peace are being neglected by the media. So I set out to uncover them, and link them together.

The number of nuclear weapons in the world.

The number of nuclear weapons in the world.

RB: What do you say to skeptics who challenge your premise, given the Great Financial Crisis, dire wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, pressing unresolved environmental concerns, and so on?

JR: I didn't know "Great Financial Crisis" was capitalized, but at least we're not calling it the Second Great Depression any more. Crises will always exist. The book doesn’t claim that everything is perfect now, just better than it used to be. In other words, we can take any bad piece of news from the present and find worse stuff in the past. What would you rather be caught in the middle of: the war in Iraq, with 4,000 US casualties, or the Vietnam War, with 58,000? Looking for a job today, with a 9.7 percent unemployment rate, or during the Depression, which was up to 24 percent (and with terrible working conditions at the jobs that did exist)? Fighting ragtag terrorists that can't blow up their own underwear, or fighting Nazi Germany? Running the risk of getting heart disease as an older adult, or dying in childbirth, as 25 percent of babies did for most of human history? It's hard not to sound callous, since our dangers today are very real and should be treated seriously, but compared to the past, we already live in a utopia. That's part of the secret in The Secret Peace.

RB: What is your favorite example of a positive trend buried beneath bad news?

JR: There are some really dramatic statistics in the book, such as how few nuclear weapons are left in the world today; how much poverty has decreased; how much land is being protected worldwide; and how health and life expectancy are increasing. But one of the most surprising ones is definitely terrorism. Terrorism, and I admit this is a difficult concept, is a good development, a sign that violence is ending. Terrorism is the last gasping breaths of human violence. It's pathetic. Our enemies are only terrorists because they are weak and lack armies. The history of war is one of a smaller and smaller percentage of humanity fighting, and an even more rapidly decreasing percentage dying in battle. Scholar Jonathan Schell describes this really well.

RB: One of the arguments in the book is not to try to eradicate threats such as terrorism but to “limit it at as much as possible so it dissipates on its own.” Can you expand on what you mean by this idea?

JR: Well, crime is a good example. Does anyone think we can achieve a world with no crime? No, but crime rates have dropped dramatically in the past 20 years. We expect crime will occasionally happen, but we still work hard to keep it at the most minimal level we can. Another good example was the wave of terrorism that hit the West at the turn of the twentieth century: anarchists. They were arguably more successful than today's terrorists (they even killed some heads of state), but they faded away because their philosophy could not appeal on a large scale. Terrorism is a last resort; most people will do almost anything else to accomplish their goals if given the opportunity. The percentage of Muslims for whom terrorist violence has an appeal is thankfully small, and we can work to make it smaller.

The percentage of the world living in extreme poverty.

The percentage of the world living in extreme poverty.

RB: Why do you think the mainstream media is so addicted to bad news?

JR: Well, it's the media's job to report bad news; it does serve an important function. Nevertheless, we still end up with a three-fold problem: not reporting the good news, not giving enough context, and sensationalizing the bad news to be even more dramatic than it actually is. Bad news is easy to see; it jumps out at you. Positive trends are often slow and less dramatic. It takes extra work to see them, and to report them in an interesting way.

RB: How do you think we can break this negative media culture cycle?

JR: I think context is the important one. Context when presenting numbers and statistics, and historical context when describing current events. It depends a lot on education; we should be teaching kids, not just facts, but how to find facts and how to sift through the news for themselves. The news also has to more clearly delineate between fact and opinion. Less of an us-vs.-them attitude, whether between political parties or between countries, would of course always be helpful, too. For now, it's up to each of us to make sure we get accurate information. I'm a big fan of The Week, a newsmagazine that aggregates a lot of other news sources.

RB: I believe we are in a wonderful time of transition moving from away being passive consumers to active participants with the voices, knowledge, and power to shape democracy and society again. What are your thoughts on this idea and how does it relate to The Secret Peace?

JR: You hit the nail right on the head. In the book, I identify three forces that are pushing society toward peace: the creation of increasing amounts of information (knowledge, technology, the arts, culture, wisdom); how many more people have access to that information thanks to the Internet and widespread education; and a new global perspective that looks at the earth and humanity holistically. Each of these compounds upon itself as well as influences the others, hence progress snowballing faster and faster.

The rise of independence and democracy in Africa.

The rise of independence and democracy in Africa.

RB: How did your experiences as a manager at Meetup influence your chapter, “Technology: Audience Participation”?

JR: Seeing people self-organize into local community groups firsthand is an incredible experience. I've met tons of Meetup Organizers who are true leaders in their communities. Seeing what a good job they do gives me great faith in all the new sites and technologies coming up — which are all about empowering individuals to be active participants, as you mentioned. This is the theme that runs through the chapter.

RB: What has surprised you the most since you joined Meetup about how people self-organize into community groups? Do you have a favorite example?

JR: I think what surprises a lot of people is how "normal" and friendly other people are. Meetup.com gets a lot of feedback to that extent. It's perhaps a little less of a surprise to me, but still reassuring. I have yet to attend a Meetup, even when dropping in on events not in my own topics of interest, where I did not see smiling faces and hospitable people: "Welcome to the Sailing Meetup! You've never sailed before? Let me tell you about it," or "You've never played Magic: The Gathering? No problem, let me show you how." I am convinced that if you were to personally meet them and engage them in something they care about, 99 percent of people on earth would just be nice folks you could have a good conversation with.

RB.: It's 2020, how do you think technology will have transformed democracy?

JR: I think people will be able to participate online in many new ways, mainly at the local level. I think states and cities are going to innovate here before countries do. And with more influence at the local level, people will also need access to clear data showing how similar policies have worked or not worked elsewhere. Also, there will be few secrets. Dirty politicians will not stay dirty for long. Corrupt deals and failed initiatives will be uncovered much more quickly. We might keep making mistakes, but we will learn about them faster, and more easily equate consequences with their specific causes.

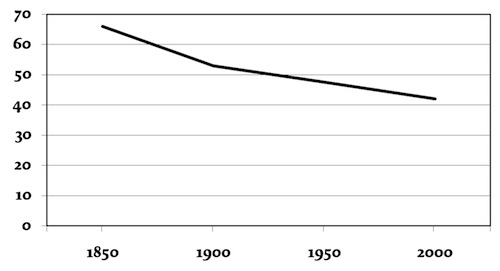

The workweek of the average American, in hours.

The workweek of the average American, in hours.

RB.: What surprised you the most whilst researching and writing the book?

JR: The speed of the good trends. I knew I could identify amazing improvements when comparing today to 100 or 50 years ago, but the changes in my lifetime alone have been impressive, and I'm only 32. When I was born, for example, the world's literacy rate was around 65 percent, and now it's 83 percent. The percentage of the world's population living in extreme poverty has dropped by more than half since then, to below 20 percent. The Millennium Development goals were only set in 2001 and are very ambitious, and yet a surprising number of countries are on track to meet the goals by 2015.

RB: What is the key message you hope readers takeaway, head and heart, from your book?

JR: Most of the events of the world are not random, capricious, and arbitrary, but are within our control. There are not a few good people interested in peace and adrift in a sea of negative criminals and monsters splattered over the media; rather, most people are good, and most citizens are working toward peace in their own humble way, and the media points out the exceptions. We need to overcome apathy and fear, and actively work toward peace, since what we do does matter and can make a difference. We need to keep up the good work.

RB: By the way, I noticed on your wonderful blog the Picasso quote, "Art washes from the soul the dust of everyday life." Why does this resonate with you?

JR: There's the issue of context again, and seeing the big picture instead of being caught up in details. It's easy to get preoccupied by our day-to-day activities and forget that transcendent beauty can be found everywhere. As an artist myself, I think one of the duties of art is to remind us of that truth.