What if there were a better way of living? A way that was more environmentally sound, more economical, more conducive to the building of community, and didn't require huge monetary investments? What if this new method of existence was already visible, and people were already participating in it, in places we had never thought to look?

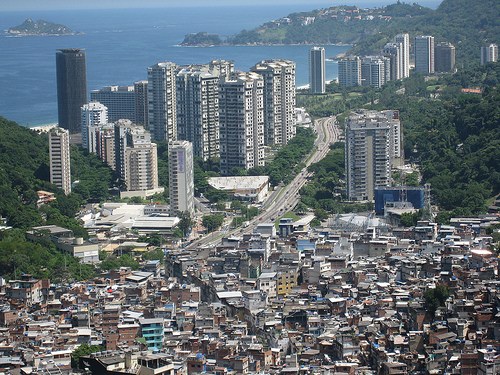

Today, in the world's most underdeveloped countries, locations where the impact of formal rule or government and capital is scarce, people are creating this other way of life. You might know these places by their other names: slums, favelas, and ghettos. We believe that these settlements offer lessons on natural development patterns, on more efficient resource and commodity use, and on sustainability. There’s this book we have, Informal City: Caracas Case, which depicts quite vividly the “informal city” phenomenon.

Environmental futurist Stewart Brand and San Diego architect Teddy Cruz have spent years trying to learn and communicate the lessons of these places: They’re high-density and walkable, two goals most urban designers consider of utmost importance when planning multibillion-dollar neighborhoods for hip, wealthy Americans. Commerce and housing in these informal cities mingle freely to the betterment of both residents and shopkeepers. In the West, we hear a lot about the need to recycle. Slum residents have always made use of post-recycled material more effectively than anyone else, including the stuff no one else will take.

Credit: Julio Aguiar

Credit: Julio Aguiar

In a March 2009 Boston Globe article, writer Rebecca Tuhus-Dubrow points out that some countries have begun to “mitigate the problems with slums rather than eliminate the slums themselves.”

As Cruz remarks in the article, these inhabitants hold to “sophisticated, participatory practices.” They have “a light way of occupying the land. Because people are trying to survive, creativity flourishes.”

These areas are the most vulnerable to floods and natural disasters, as recent events in Haiti make clear. The total absence of planning is not a goal for urban planners to strive for. But people in these areas have been surviving and developing with very little capital or government involvement, and they’re becoming increasingly good at it. If we can learn what these places have to teach us, we can find better ways to live in our own local habitats.

We call our interpretation of this idea the self-generative community, or SGC.

Credit: Ramon Llorensi

Credit: Ramon Llorensi

The Self-Generative Community

Modern life is frustrating and disappointing; we work too hard to spend too much for things we hardly want. The most obvious alternative to our feelings of technological discontent and disconnect is leaving the world behind, quitting the high-stress job, abandoning society with its regulations and failing institutions, moving somewhere temperate, and looking out for oneself. This is popularly referred to as “going off the grid,” meaning the electrical grid, but really referring to any and all sense of society or obligation.

We propose living on the grid of a new urban fabric that distributes self-generated resources—food, learning, skills, human talent, and labor—and creates natural connections among inhabitants and nature. This way of living draws from the lessons that the world’s poorest inhabitants have to give us without romanticizing the difficult and unfortunate aspects of impoverishment. The SGC is a portrait of humanity not at its poorest, but at its most resourceful, responsible, and aware of its surroundings. The objective of the SGC is to realize homegrown socioeconomic sustainability by investing in the proper handling of the natural environment and technology.

How do you create an SGC? We see three steps, which involve uncovering the natural resources of the area, tapping into the appropriate use of both natural and social capital (such as building partnerships, cooperative business enterprises, etc.) in order to further the economic development, and finally integrating a sophisticated mix of programs into a high-density model.

Credit: Alicia Nijdam

Credit: Alicia Nijdam

Step One: Restore. Reconnect the Earth and the Sky

Restore, in this context, refers to bioremediation or restoration of the natural cycles as needed. Nations in the developed world have altered the urban landscape to a point where water hardly reaches soil for filtration and drainage, and rooftops squander solar energy that nature had used productively. There are better ways to treat both those resources.

If you’re talking about building an SGC at one particular urban area, fulfilling step one can be as simple as ripping out urban pavement that isn’t actively supporting a structure and allowing rainwater to be absorbed into the ground. Communities around the world function effectively with a lot less pavement around than do people in the industrialized world. Again, the point is not to create a situation without adequate land grading, or where un-zoned structures impede the flow of rainwater, possibly causing flooding. This is an unfortunate fact of life in many of the world’s poorest communities. We propose simply the removal of unnecessary pavement in an intelligent, considered way.

Does your city not want you to rip up the sidewalk? Some local governments are giving ideas like this serious attention. Starting in June 2010, the state of Maryland will be enforcing a new law stipulating that, if you’re developing a site of a particular size, you’ll need to meet the highest water-management requirements. But for a picture of what truly effective water management looks like, go to a forest.

Credit: Alessandro Casagrande

Step Two: Plant and Energize the Seeds

This refers to the building of new social, economic, and environmental infrastructure based on cooperative capacity, or the amount of time and talent the neighborhood is willing to invest to make their area economically self-sustainable.

Harvesting renewable energy sources locally to generate immediate revenue and help sustain development is one key to realizing step two. This could mean passive solar energy co-ops, where neighborhoods build their own photovoltaic systems on rooftops. It could mean inner-city biofuel-crop growing, perhaps in basement hydroponic gardens. It could be all of the above. The idea is to start harvesting available renewable energy and use it to power local businesses, or sell it back into the grid. Power generation becomes a community business. In this way, it’s integrated seamlessly into the area’s future development.

This is directly connected to the informal city way of life. We in the developed world commonly misperceive slums as economic dead zones, as basket cases, when in fact they’re hotbeds of self-sustaining commerce. That’s as it should be.

Informal cities are also mixed use in their layout. That means commercial, residential, and light industrial/agricultural activities take place side by side. The key here is to capitalize on cooperative relationships, seek potential partners within the community, and develop strategies for integration. Meanwhile, the SGC must also be adaptable and versatile. Communities change constantly; SGCs reflect and support that change.

Credit: Arden

Credit: Arden

Step Three: Nourish, Breathe, and Grow

The third step is to introduce a series of connected programs between local government and the community. In terms of proposing programs to fit community needs, there is no one-size-fits-all strategy. We presented a plan to the city of Baltimore a few years ago called Hidden Walls. The plan involved rehabbing blocks of abandoned row houses. This was a high-unemployment inner-city neighborhood. The community in that situation needed a means to build equity and value into their area. They also needed to shelter their kids from the notorious Baltimore drug-dealing scene. Our final proposal was a modern iteration of the Middle Ages manor village, but with high-speed Internet and without a feudal lord. The programs we proposed were geared mostly toward community education and neighborhood economic development.

We suggested different program solutions at another location in Dallas, where the community was trying to make use of abundant sunshine and open space. The key is to add new programs and transform the relationships of the actors as more people move to the location and change it. There is no formalist approach to building a self-generating community. It’s more systematic; complexity grows itself naturally in keeping with how community actually develops.

In the context of every city and in the life of every neighborhood, there is a synergy that brings up the potential to develop something unique, to rebuild the urban environment to reach its fullest potential. There is no MAKE GOOD button for creating a more equitable environment, just like there is no GO AWAY for unwanted elements and no PUT THERE for discarded resources.

To regenerate our cities and communities and restore our feeling of place, we must stop perceiving ourselves as mere consumers. If we can become inhabitants, constituents, and producers, we can achieve a different sort of habitat, one that is environmentally, sociologically, and culturally self-sustaining precisely because it honors all of these vital areas of life, equally.

Credit: Leszek Wasilewski

Originally published in THE FUTURIST. Used with permission from the World Future Society