In southern Oregon, Annie Hoy was about to head to the third training session for entrants in her contest for startups — but she wasn’t sure if she’d reach her goal of five applicants by the mid-August deadline.

Getting entrepreneurs to throw their hats in the ring was taking a bit more hand-holding than in Silicon Valley, where you can’t toss an iPhone without knocking a fledgling founder in the head. That’s not just because Hoy’s prize money, at $3,000, was miniscule compared to the millions offered in some entrepreneur pitch competitions, or because tiny Ashland, whose main economic driver is a well-known Shakespeare festival, lacks a tech startup culture.

It’s because Hoy’s competition is built around a different model altogether: cooperatives. “The feedback from people who have gone through the introductory class is: ‘Oh my god, how do I write a business plan about a co-op? I’ve written a business plan for my regular business, but I don’t know anything about a co-op,’” said Hoy, who’s worked for the Ashland Food Cooperative for a quarter-century, and is running the competition for a local alliance called Rogue Co-ops. “It’s hard enough to start a sole proprietorship. Starting a co-op is a long and complicated ordeal when you get right down to it, and it’s not just you – you’ll have members that you’ll engage in order to make it go.”

Cooperatives are increasingly taking a page from the Silicon Valley playbook and launching cooperative accelerators, academies, incubators and at least one contest – Hoy said Rogue’s competition is the first – to help build the next generation of cooperatively-owned businesses. Their goals are in line with the zeitgeist: democratizing ownership and giving employees, consumers, and communities a stake in the businesses where they shop or work. Co-op accelerators and incubators like Start.coop in New England, Sismic in Montreal, and Green Worker Cooperatives in New York, are grooming new cooperatives to think beyond just their local communities and build business models that can scale, allowing them to connect to new regions and demographics.

Joint ownership and democratic control are at the core of co-operative principles, though co-ops can be structured so that instead of making collective decisions directly, members vote for representatives who set policy and oversee management decisions. Sharing ownership typically means sharing wealth. The vast majority of worker co-ops in the United States had a pay ratio of 2-to-1 between top leaders and line workers, as compared to the 303-to-1 average CEO-to-worker pay ratio of large corporations, according to a 2017 report from the Democracy at Work Institute.

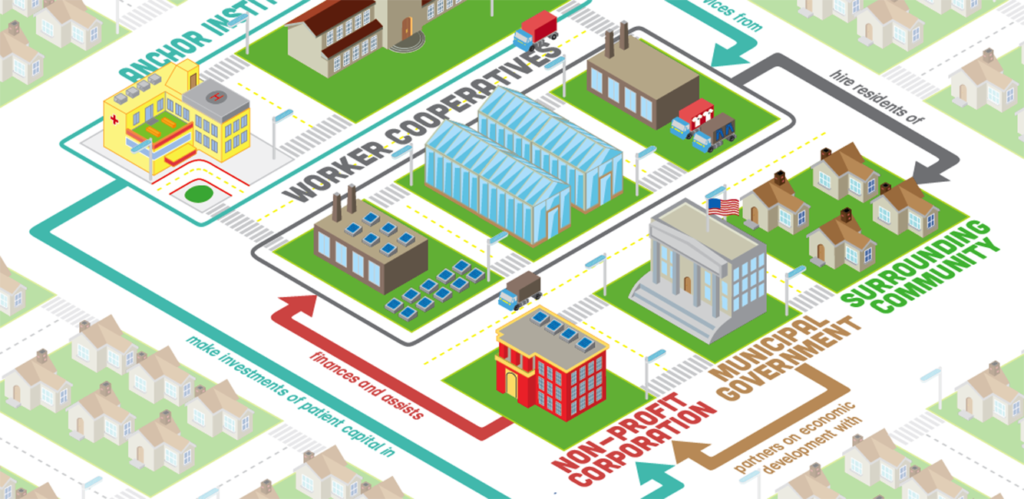

“We want to really build an economy that is structured through connections of mutual interdependence,” said John Duda, communicators director at The Democracy Collaborative, which released a report in April on how cooperatives can grow and scale. “There’s just a real explosion of work in policy, in finance, in creative ethical and democratic finance techniques.” Currently, the U.S. has roughly 450 worker co-ops and is adding about 25 annually, but with the growth and increased sophistication of efforts to expand the sector, Duda said, “I would not be surprised if you had a 10-fold increase in the size of the worker co-op sector in a year.”

Co-op accelerators compete with the profit motive

Boston-based Start.coop, a co-op accelerator founded about a year ago, just graduated its first cohort of five co-op startups in May – and snagged its first win in a pitch competition at SEED, a San Francisco conference for early stage ventures. Cohort member Savvy Cooperative walked away with the judges’ prize of $12,500 for its patient-owned platform that connects health care companies doing market research with patients using the platform. Most of Savvy’s competitors were structured as traditional corporations.

Two of the cohort’s other startups fit within a growing category known as platform co-operatives, a term describing apps, websites or other types of technological platforms that are cooperatively owned and democratically governed. Imagine Uber – but owned by drivers who also get a say in how it’s managed.

In fact, one of the co-ops in Start.coop’s first class is Driver’s Seat, a co-op that collects location data from rideshare drivers to both help them optimize their earnings and bring in additional income from sales of the aggregated data to industry and civic organizations. The other platform co-op, Expert Collective, connects academic experts with big corporations in need of their expertise, with a goal of capturing a portion of the management consulting fees paid by those companies.

The two Start.coop fledglings have joined a growing platform co-op universe. An online directory of platform co-ops lists more than 100 around the world.

While traditional accelerators offer seed money in exchange for an equity stake of up to 8 percent in the companies they foster, Start.coop takes a different approach. It seeds the co-ops it selects for its program with anywhere from $10,000 to $20,000, and each one then has to commit to pay that money back with a small percentage of revenue. “Basically, as they’re successful, they’re helping to pay it forward so that we can fund a future entrepreneur in their seat a few years down the road,” said co-founder and CEO Greg Brodsky. “We’re trying to align the incentives so we have a vested interest in making sure they grow.”

Cities warming up to co-op accelerators and incubators

Five years ago, New York City launched the Worker Cooperative Business Development Initiative, which funneled $1.2 million to 10 partner organizations to “spur the creation of new worker cooperatives, and help small businesses transition their business into the worker cooperative model,” according to the 2015 report on the program’s first year in operation.

Since then, funding has more than doubled to $2.9 million and 142 new co-ops have been created. South Bronx-based Green Worker Cooperatives has been responsible for launching more than 30 of them. Although it doesn’t make financial investments like an incubator or accelerator would, the GWC program is quite selective, accepting just a quarter to a third of applicants – and thanks to the city funding, GWC can offer its curriculum for free. Participants in either of the twice-yearly cohorts get 20 weeks of training, including legal assistance, mentoring with successful entrepreneurs, and access to peer support throughout the program.

“A lot of people call it a lean MBA in five months,” said communications coordinator Raybblin Vargas. “It’s a very, very rigorous program. It kicks your ass – I know because I went through it.” She said she’s still looking to get a space and permits for her proposed tech café, but she has the legal structure in place so she can get It going once she clears those hurdles.

“We really believe that we are building a movement,” Vargas added. “Cooperatives are an extension of our strong belief in creating a more democratic, just society based on a vision of equality and environmental justice and all kinds of -isms that have kept our communities down.”

Increasing diversity among founders is part of that vision, said Jonah Fertig-Burd, director of cooperative food systems at the Cooperative Development Institute, a western Massachusetts-based business development organization for co-ops.

“One of the things that we’re seeing nationally in the worker co-op development world is that a growing number of new startup co-ops are being led by people of color, Latinx communities, and women – who have been traditionally been left out of the economy and have lacked access to resources,” he said. “Cooperative ownership is one way to really shift that power, shift that wealth, shift the capital to communities that need it,” said Fertig-Burd, “and do that in a way that’s participatory, democratic, and equitable and really building that community wealth together.”

New York is one of many US cities that have started or increased support for cooperatives in the last decade including Cleveland, Ohio; Berkeley, California; and Jackson, Mississippi. The federal government is starting to catch up with last year’s passing of the Main Street Employee Ownership Act and additional legislation currently in the works, all part of a growing national trend.

Increasing international efforts

Internationally, co-op incubators are taking diverse approaches to their work and innovating around how co-ops are structured and developed. In Canada, the Montreal-based Chantier de l’économie sociale (Center for the social economy), a nonprofit created to support new collective business and social enterprises, announced in May that it was launching a province-wide network of 19 cooperative incubators, called Sismic. The effort is focused on supporting businesses led by students and young adults and aims to fill a gap in the business training programs available to post-secondary students.

A group in Melbourne, Australia took a radical approach to co-op incubation itself when it founded The Incubator Co-op two years ago. Rather than having a set curriculum and group of trainers, the organization lays out a loose four-step process to co-op development – form, organize, fund, operate – and takes a crowd-sourcing approach. That means using peer-to-peer learning and skill sharing to help entrepreneurs build their business.

Five of the eight startups that joined The Incubator Co-op’s first cohort in February were expected to be launched by the end of June, while the two remaining (one dropped out early) needed more time to fully develop, according to an update on the group’s website.

As those results demonstrate, intensive training isn’t always enough to help cooperatives succeed, said Fertig-Burd, who has worked with at least a half-dozen cooperatives and affiliated organizations. He founded a program in 2015 called Cooperative Design Lab that trained about 20 cooperatives during its two years in operation, and one of the lessons he learned from that experience and his research was that “to develop a co-op it takes a lot of ongoing support.”

“It’s not enough to do a short training program and expect that that co-op is going to be able to go off on its own afterwards,” he added. “It’s really important to build in follow up work, whether that’s tech assistance or peer mentoring, connection to funding, financing, or other resources that might be needed.”

Successful cooperative ecosystems like Spain’s Mondragon Group, a federation of 266 companies and cooperatives that employs more than 80,000, have tightly woven networks of supporting institutions that provide help with financial, legal, policy, advocacy, and education needs, Duda of the Democracy Collaborative pointed out.

“All of these things need to be put in place in order to grow cooperative businesses,” he added. “As people are getting a handle on how to build these ecosystem incubators and accelerators, we’re starting to see different possibilities for scale emerge in a really exciting way.”

Internationally, three million cooperatives employ 280 million people, or about 10 percent of the working population, in industries from finance and insurance to agriculture, housing, and health, according to the International Cooperative Alliance. In the U.S., Duda sees substantial growth ahead as new cooperatives develop that can provide interlocking support to one another: “They’re a pattern that’s powerful enough to really base an economy around.”