Major metropolitan cities produce a mind-boggling amount of civic data on a daily basis. But disenfranchised communities and the social organizations who serve them lack the resources to delve into this deluge of data. New York-based non-profit DataKind (formerly Data Without Borders) aims to address this skill and resource gap, connecting volunteer data scientists and developers with social organizations lacking the money, time, or the skills necessary to better serve their communities and address social ills through data analysis.

As DataKind founder Jake Porway stated at Code for America’s second Big Data for the Public Good seminar, (which I recapped for event sponsor Greenplum,) open data without skilled analytics is “like giving crude oil to people…Open data is not useable data.” This philosophy is key to DataKind’s mission and informed its first Chicago DataDive last weekend, which connected volunteers from Chicago’s emerging open data community with local non-profit organizations for 22 hours of hacking, research, and analysis.

DataKind connects researchers with social organizations through three programs: the DataFellows fellowship, which assigns data scientists to work with a particular organization, DataCorps, a distributed network of volunteers, and city-specific weekend DataDives. The Chicago DataDive is the fourth the non-profit has organized since its kickoff in New York City on October 14, 2011, which explored “stop-and-frisk” incident data reported by the NYPD in 2010, on behalf of the New York Civil Liberties Union.

Big Data for the Public Good | Seminar 2: Data Without Borders | Jake Porway from Code for America.

For the Chicago event, DataKind partnered with the American Red Cross of Greater Chicago, Children’s Memorial Hospital, and Enlace Chicago, an organization aiming to reduce violence and encourage educational advancement and economic development in the city’s Little Village neighborhood. Each organization provided internal data as well as representatives to collaborate with volunteer data ambassadors and attendees. The goal? To identify internal operational challenges and explore how deep, dedicated data analysis by trained professionals could help the non-profits better serve their communities.

Big Shoulders, Narrow Scope

Jake Porway speaks to the Enlace working group.

DataKind chose Chicago as the location for its fourth DataDive based on the high level of interest expressed by the “city’s amazing data and tech scene” said Porway, and the open data initiatives championed by City of Chicago data gurus Brett Goldstein and John Tolva. To ensure the events yield useful results, DataKind is equally selective when choosing partner social organizations. The problem an organization wants to tackle “has to be narrowly scoped,” said Porway. “We know we’re not going to solve an endemic problem in a weekend.”

DataKind vets the data, so that attendees don’t spend an entire weekend hacking the data into a useable state. “Anyone who knows data knows that data cleaning is a big problem,” he said, acknowledging that some degree of data cleanup is inevitable at this stage. They also look for “buy-in from someone at the ground level and the ‘c level’” to gauge the level of engagement and commitment within the organization.

Following a debriefing and cocktail mixer Friday evening, the 70 attendees met at startup incubator 1871 Saturday morning to break into three working groups. Representatives from each non-profit articulated the problems they hoped to address over the weekend, while the data ambassador served as facilitator and translator. The questions each organization presented, detailed on the event wiki, were narrowly focused given the limited time and available data.

The Chicago Red Cross’s question was strategic: where should the organization allocate resources to prevent disasters? “The kind of organization that we are, serving in a lot of different capacities — we respond to disasters, provide health and safety information, collect blood, provide tracking services on an international basis — creates a tremendous amount of data,” said Benjamin R. Kessler, Manager of Database Operations for the Chicago Red Cross. “Keeping track of that data is an ongoing problem, and we certainly do not have a comprehensive handle on it. The fact that the DataDive was happening was coincident with the fact that I was asked by the organization to look for better ways of organizing our disaster response data, so it was a nice hand-in-glove coincidence.”

Benjamin R. Kessler speaks to the Red Cross working group.

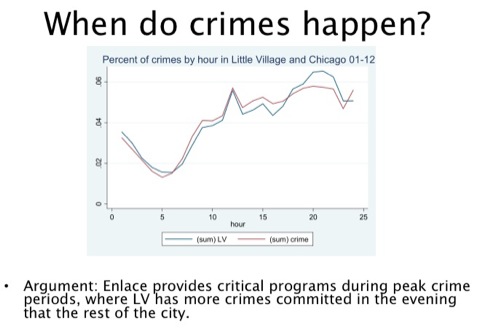

Children’s Memorial Hospital aimed to identify the who, what, and where of youth violence in Chicago, and how geographic data could be used to track the risks and assets within a particular community. Enlace’s team looked at whether they could find correlations between school performance and nearby crimes, and track crime spikes over time. For 14 hours on a sunny spring Saturday in downtown Chicago, attendees brainstormed, discussed, and peered deep into a web of terminal windows.

Spending a free weekend cleaning datasets and building frameworks for further analysis isn’t everyone’s idea of a good time. So “what motivates people to spend their weekend staring at rows of data?” asked Young-Jin Kim, Managing Director for Drupal developer Emphanos. “It’s a puzzle, and data geeks don’t get an opportunity that often to dig into other people’s data,” he said. “It’s usually private. What interested me here is finding out what other people use. There’s new tools being developed all the time and you can’t keep up. I’m a strong believer in tool building in general. That’s what got us out of the caves and into buildings like this. Sharing these tools is how we got here.”

Tools for Social Change

12 hours in, the DataDive was still going.

Developing these tools is fundamental to Datakind’s goal to kickstart ongoing projects. The research and visualizations produced during the weekend serve primarily as useful proofs of concept, demonstrating to the organizations what can be done with data, and what new insights and questions emerge. Porway emphasized to attendees that their efforts were foundational: providing organizations with a framework to work with data, while connecting them with potential volunteer developers and researchers.

“One of the challenges is that it’s just a day,” said data ambassador Mike Stringer, Managing Partner at Datascope Analytics and organizer of the Data Science Chicago meetup. “I like that Jake is emphasizing the longer-term vision, and trying to look toward how we can be useful to these types of organizations in the future. The central challenge today is just getting a handle on the data, figuring out the format of it, what’s in there — it just takes time and every person has to struggle with it individually and try to get their head around what’s actually in there. That takes half of the day, and so you only have the other half of the day when you have some idea of what’s in there, and that’s just not much time. You’re not going to solve the problem of crime in Chicago with a half day of hacking.”

The Enlace team deep in data.

Ultimately, it’s about building sustainable relationships that will address real ongoing problems. DataKind collaborates with the organizations before the DataDives to ensure that the project is worth their time, and that attendees will be able to hit the ground running. Since DataKind is “cultivating on the front-end, everybody is up to speed and comes to the table to have an effective conversation,” said Kate Eyler-Werve, a local change management consultant currently writing a book about building community around public data for O’Reilly Media. “That’s very difficult to do, and the fact that they’re doing it with only three groups at a time is significant.”

“Let’s face it,” said Eyler-Werve, with characteristic Chicago candor. “Non-profits are pressed for time, they don’t necessary have somebody who is willing to sit here and listen to some yahoo who may or may not be helpful. What I’ve found is that there’s already this pretty high level of distrust and animosity between the development community and the not-for-profit community. I was at an Idea Hack a couple weeks ago, and the developers said, ‘I just want to be able to come in and devote one hour to something that would be useful.’ The non-profit people were like, ‘yeah, you’re going to build us some BS website that only you know how to build and it’s going to break and we’re going to be worse off than before, so I’m going to dump all my time into this.’”

“It was a completely unproductive conversation, and it was the wrong conversation to have,” she said. “You’re talking about infrastructure and websites instead of talking about data and what you can do with that, so trying to shift that conversation is a challenge and I think the DataDive is doing a fine job.”

Bad Data, Due Diligence, and the Trouble With Crime Maps

Jake Porway addresses the attendees Saturday afternoon.

Producing useful frameworks and a community to continue the work is essential. DataDive attendees are ultimately limited by the data sets available during the short window of time allotted. Effective analysis of the many factors contributing to social ills demands significant time and an ongoing effort.

Simple visualizations that fail to account for the breadth of relevant factors can be more than merely misleading. They can actively harm communities they aim to serve, a concern shared by a number of attendees. This is a central issue for those working with crime data — simplistic heat maps of crime incidents that lack demographic and socioeconomic data are not only ineffective, but can exacerbate existing prejudices.

“There needs to be more due diligence with regard to crime mapping,” said Marshall Smith, a student at the University of Illinois at Chicago. “The challenge is having the right sets of data for the right kinds of questions,” he said. “We need to have a very thorough understanding of what questions come out of the data.”

Such sentiments were echoed on Sunday morning by Tzyy-Chyn Hu, Director of Clinical Research for the Cook County Bureau of Health Services. “No data is better than wrong data,” she said. “These organizations depend on this data for funding. When decision making is made from the wrong data, it’s a disaster,” she said, emphasizing the wide range of factors — socioeconomic factors, location, race, policy, even weather — that contribute to crime rates. “Multivariate analysis is essential,” she said. “You need some kind of reliable measurement and to bring in all the possible factors…Data is just numbers. You get wisdom from your interpretation.”

Sustaining the Buzz

The results of the weekend’s labor, presented by each Data Ambassador on Sunday morning, represented only a beginning — products of an all-too-brief dip into the available data. Nevertheless, the presentations posed compelling questions, which are documented in depth on the wiki. The Red Cross team found that fires are often clustered in certain neighborhoods, providing insight on where the organization could more effectively allocate fire prevention efforts. They found a strong correlation between disaster responses and per capita income, race, and population, though not population density. They also mapped the disaster response data, demonstrating to the organization how free and relatively user-friendly tools like Google Fusion Tables offer valuable insight.

The Enlace team focused more gathering public school data, identifying trends in Little Village crime data, and establishing research approaches. The team working with Children’s Memorial Hospital focused on translating the data for further analysis and creating a set of tools and processes for the organization, including a process for adding community area, neighborhood, and census tracts to 2011 Chicago crime data, and a Python script for geocoding addresses in the randomized Illinois Violent Death Reporting System data.

For their part, representatives from the organizers left the DataDive on Sunday afternoon satisfied that their time and resources were well-spent, and that they were leaving with effective tools for continued research. “I don’t normally realize that we’re as silo’d as we are, so it was nice to build a broader set of contexts and see that the same problems we deal with are dealt with in a lot of different areas,” said Jennifer Cartland, Director at the hospital’s Child Health Data Lab. “There’s a different skill set here than what we have in our office. We have a lot of in-house tools that allow us to do statistical analysis and work with data, but we don’t have the skills to put together what would be a living resource on the Internet. It got our thinking a lot further along in terms of what we need. We have a much more concrete idea of what our end game is.”

Rebecca Levin, Strategic Director at the Injury Prevention and Research Center, explained that the event helped establish new strategies for working with data from organizations participating in the hospital’s Strengthening Chicago’s Youth (SCY) program. “We’re really excited about applying this idea within the SCY collaborative” she said, “for our member organizations to bring their data so we could match them up with local data scientists who can help them look at the data and what they could do with that.” Levin expressed strong desire “to take the tools developed this weekend and help other groups in Chicago look at the picture in their communities.”

This energy was shared by attendees. Members of the Red Cross team formed an ongoing Data Pot Luck — a regular meetup for “data diving and good food” — to continue the work and momentum from the DataDive. Dean Malmgren, Managing Director at Datascope Analytics, created a Chicago Data Meetups stack on Delicious as a resource for the emerging community.

Mike Stringer presents the Red Cross team’s work and conclusions.

Such examples bode well for future of what Neal Gorenflo dubbed the “data-driven civil society.” But facilitating the level of ongoing engagement necessary to effect lasting social change is a challenge facing all organizers of civic hackathons, requiring a shift in both behavior and culture.

“How do you get people to change their behaviors so that a one-time intervention can actually bear fruit over the long term?” asked Eyler-Werve. “One-time interventions are great — they develop a lot of buzz, get some new ideas going, some new energy — and that’s fantastic. Even if that’s all that it does, I think that’s still useful, because we’re still getting people to think differently.”

Though the participants in the DataDive were enthusiastic to connect with their communities and eager to keep momentum going, the data science resource gap shared by many social organizations won’t be solved with soda and beer-fueled weekend hacking marathons alone. “We do need to think about how to sustain the engagement, and I don’t think that asking the developers to devote all their weekends to this is the right answer,” Eyler-Werve said. “I think non-profits and also foundations need to figure out, ‘this is something valuable, this is something we should fund, so let’s push this forward.’ That’s going to be pretty integral to the sustainability of this.”