“Viral”, a central metaphor for social media and the Internet, is particularly apt because nothing is quite as shareable as the flu virus. But can the metaphor be made literal? Does word of the flu itself go viral across social media? And if so, is this the one time social media can be used to curb virality rather than spread it?

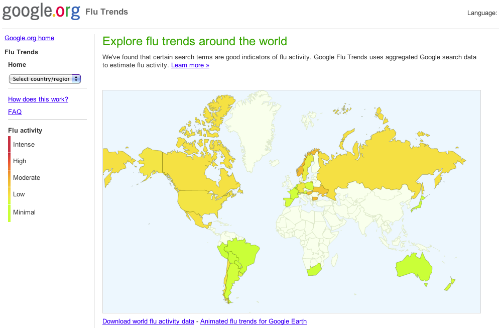

Google thinks so, putting considerable resources into Google Flu Trends, a tool that follows online chatter about flu–from news articles about outbreaks to the posts of stuffed-up bloggers stuck in their bed with a box of Kleenex. Google Flu Trends had its coming-out day during the Swine Flu scare, when the Centers for Disease Control requested the company to aggregate and analyze search queries to estimate the extent of the outbreak.

Yet Flu Trends suffers from the same problem that Google is trying to improve with Google Instant: Google has traditionally been great at telling you what happened yesterday or six months ago, but not at displaying trends in real time. To get more up-to-the-minute results, researchers are turning their attentions to Twitter for its wealth of social data broadcast every moment.

Culotta and his team sifted through over 500 million tweets from August 2009 to May 2010, and found a 95% correlation with statistics from the CDC, only reported in real-time. The advantage is not only in having real-time data to better respond to trouble areas, it's also that it's predictive when combined with advanced analytics. This real-time data can then be compared to past trends to identify potential hot spots before contagion spreads to them, which could allow agencies to recommend members of at-risk communities to self-quarantine and hyperlocal disease response efforts.

Of course, despite these considerable benefits, there is something vaguely Orwellian about such monitoring and predictive power. Since the data and methodologies are the domain of a small group of government agencies, researchers, and corporations, the public would be placing a lot of faith in an organization such as Google to ‘not be evil’. A preferable approach might be to open-source the data and methodologies and analyze it in a completely transparent manner, though without proper training such an approach could encourage undue hysteria.

Culotta himself acknowledges other issues in the methodology: a recall of flu medicine could dramatically skew the results, for example. And referring to the Haiti Cholera Outbreak, Culotta asks “How many Haitians use Twitter or Google?”

Regardless, even if social trend aggregation tools like Flu Trends and Twitter provoke some serious considerations, they offer an opportunity to identify and respond to outbreaks quicker than ever. And for researchers and doctors, once such tools mature, they could make a significant difference in the extent of outbreaks and very literally save lives.