This essay draws on the words and research of Alison Hawkes, Bernice Yueng, Christopher D. Cook, Jeremy Adam Smith, and Victoria Schlesinger, who worked together to investigate the Treasure Island redevelopment in San Francisco. The original articles appeared in a special section of the June print edition of the Public Press, a nonprofit news organization. The Treasure Island investigation was financed in part by Shareable.net’s readers through the crowdfunding journalism site Spot.us. In October, 2010, the Society of Professional Journalists Northern California chapter selected the investigation to receive an Excellence in Explanatory Journalism award.

San Franciscans tend to view the artificial Treasure Island as a blur on the bridge to the East Bay: the 400 acres have been semi-abandoned since the Navy shut down its base in 1997.

That's about to change. In the next six months, San Francisco officials and a consortium of private developers will begin to finalize legal papers for Treasure Island’s future as a high-density eco-city. Boosters hope the project will deliver jobs to construction workers, profits to contractors, taxes to the city, and new homes in a tight housing market.

But the Treasure Island redevelopment, which aims to build the most ecologically sustainable community in the world, delivers something else as well: a positive self-image of San Francisco as a forward-looking, avant-garde, socially and environmentally responsible metropolis. Nothing excites the utopian impulse more than a blank slate — and with its wide-open landscape, boarded-up buildings, and transitional ownership, that’s exactly what Treasure Island provides.

Treasure Island today. Credit: Kenn Wilson

Treasure Island today. Credit: Kenn Wilson

Renderings in the master plan of gleaming towers, parks, and gardens suggest harmony, community, and sustainability. It embodies almost all of the design ideas we promote on Shareable.net. Indeed, my first reaction on seeing the master plan was to be awed and excited — and I wasn’t alone: most local coverage of the development has bordered on fawning. “If Treasure Island is reborn along the lines being touted, the result will be a neighborhood like none the Bay Area has seen,” writes architecture critic John King in the San Francisco Chronicle. Meanwhile, green sites like Inhabitat have presented the project as architectural porn.

Yet the promise of an urban Treasure Island, one of the most complex and risky developments in San Francisco’s history, has for more than a decade been wrapped up in a process driven by power and influence. The mayor got near total control. Political friends got plum jobs and contracts. Critics were exiled. City and state conflict-of-interest laws were waived. Independent inquiries and the will of voters were nakedly rebuffed.

This history is not merely academic: the experience of other attempts to build ecological utopias suggests that these political and financial twists and turns can sink even the most earnest attempts to put Shareable.net’s ideals into practice. It’s easy enough to articulate new, Platonic ideals for building and community — but in the Aristotelian real world, developers and contractors do what they do for a profit; politicians and bureaucrats work in sausage factories, not ivory towers.

Thus the Treasure Island redevelopment is a fascinating case study in how shareable ideals are translated into the real world of money and politics — one that might hold lessons for community activists, architects, planners, and officials in other communities.

Ecotopia Emerging?

Make no mistake: The Treasure Island redevelopment plan is rooted in ideals shared by Shareable.net and many of its readers. The plan instantly reminded me of Ernest Callenbach’s classic 1975 novel Ecotopia, which speculates what would happen if Northern California, Oregon, and Washington separated from the United States and tried to develop an ideal “stable-state” economy and culture.

Branded by some as a hippie-dippie relic, the book holds up shockingly well in 2010 — and it continues to be discussed after having sold more than a million copies in nine languages. (Last week, Shareable.net published a conversation with Callenbach and urban farmer Novella Carpenter that explores Ecotopia’s roots and impact on younger generations.)

Some of Callenbach’s wacky, far-out proposals — like requiring every Ecotopian household to sort waste into compost and recycling — are now the twenty-first-century reality in many cities around the country. Other ideas — like designing streets for walking and biking — have come to seem perfectly reasonable in the age of rising sea levels, and are official policy goals in some cities. The following laundry list could come from Callenbach’s Ecotopia — but, in fact, these items come straight out of the Treasure Island sustainability plan:

- Land use policies that emphasize strong neighborhoods, walkability, and a network of attractive public spaces

- Sustainable design practices creating effective nodes for alternative transportation, with all residences within a 15-minute walk to a San Francisco ferry

- A 22-acre farm that aim to produce enough food for 2,200 people, selling exclusively to residents, groceries, and restaurants on the island

- Sixty to seventy percent of roofs will sport solar panels and the island’s two residential towers will be covered with photovoltaic skin; wind turbines will cover the island

- Open space planning that minimizes energy and water consumption, encourages native plant usage, and promotes biodiversity.

Great. But Treasure Island is certainly not the first attempt to build a city that aspires to high ideals — and the history of such efforts to leap from master plan to built environment should give us all pause.

The old town of Stevenage. Credit: Wikipedia Commons

The old town of Stevenage. Credit: Wikipedia Commons

In 1946, for example, the British government passed the New Town Act, which sought to establish a ring of master-planned, self-contained, egalitarian “garden cities” around London, in part to reduce the population and pollution of “the Big Smoke,” as coal-dusted London was once called.

Inspired by Edward Bellamy’s 1888 utopian novel Looking Backward 2000-1887 and Ebenezer Howard’s 1898 book Garden Cities of Tomorrow

— both 19th-century counterparts to Ecotopia — the Garden City movement did not use our contemporary language of sustainability but it did try to use architecture and urban design as tools of social and environmental change. The ideals that drove the New Town Act were not modest in their aims: they sought nothing less than to build cities that would, through the magic of their design, reconcile society and nature, labor and capital, tradition and modernity.

It goes without saying that the garden cities that were actually built under the New Town Act never even came close to achieving these goals. London’s bureaucrats collided head-on with the people who already lived in the planned garden city sites — and their struggle revealed deep fissures between top-down modernist planners and the culture of English village life.

The new, modern Stevenage. Credit: Wikipedia Commons

The new, modern Stevenage. Credit: Wikipedia Commons

In his 1953 study of the real-world impact of the New Town Act, Utopia Ltd, the sociologist Harold Orlans describes a disastrous public hearing about the Stevenage development. At one point the Minister of Town and Country Planning imagines Stevenage as what we would call a cohousing space, organized around a community green with communal kitchens and cooperative nursery schools. This might sound terrific to the readers of Shareable.net, but the residents of Stevenage didn’t agree. From the transcript of the Minister’s talk:

“I want to carry out in Stevenage a daring exercise in town planning. (Jeers.) It is no good your jeering: it is going to be done. (Applause and boos. Cries of “dictator.”)

The opposition wasn’t merely the byproduct of top-down planning, though the ministry’s authoritarian impatience didn’t help matters; Orlans’s study makes it clear that residents actually opposed the shareable ideals behind the plan. The residents delayed the project — when put to the voters, a majority came out against the entire plan — but they couldn’t stop it: In the 1950s and 60s, the region’s population rose dramatically as the government built its garden city. The result was not a revolution in daily life, at least not the one planners hoped for; instead, a quaint English village was simply displaced by modern, car-centric malls and suburbs.

Indeed, the sharpest irony of the Garden City movement — the one that should leave today’s utopians truly chastened — is that its real-world manifestations in both North America and the United Kingdom have been blamed for contributing to the sprawl and car-culture that has warmed the globe and isolated us from each other. By calling for a maximum of twelve houses to an acre, so as to create a healthy little belt of green around every family, the Garden City movement was one of many cultural forces that helped create today’s suburban sprawl.

Architect's renderings of planned Chinese eco-cities like Liuzhou (above) look terrific. But most of them will never be built.

Architect's renderings of planned Chinese eco-cities like Liuzhou (above) look terrific. But most of them will never be built.

In these ways, yesterday’s utopias become today’s dystopias. In response, new and improved utopias arise — and today, eco-cities like the Treasure Island development are the inheritors of Garden City ideals. Unfortunately, other grand Ecotopias have not gone as planned: Critics like Christina Larson, writing in Yale Environment 360, argue that master-planned eco-cities like Huangbaiyu, Liuzhou, and Dongtan in China, which were all greeted by waves of enthusiastic press, have so far fallen far short of their goals:

Dongtan and other highly touted eco-cities across China were meant to be models of sustainable design for the future. Instead they’ve become models of bold visions that mostly stayed on the drawing boards — or collapsed from shoddy implementation. More often than not, these vaunted eco-cities have been designed by big-name foreign architectural and engineering firms who plunged into the projects … with little feel for the needs of local residents whom the utopian communities were designed to serve.

But Treasure Island is in some ways quite different from those projects. Its commitments to stormwater wetlands and clean energy are legally binding, unlike in China. And unlike the Chinese projects — or, for that matter, Stevenage — the Treasure Island redevelopment has been subjected to 15 years of intense expert scrutiny and public involvement. During a recent trip to Treasure Island, I saw signs everywhere advertising meetings for residents to give feedback on the project. When I asked one two-year resident if he’d had a chance to make his voice heard, he just laughed. “I’ve had too much opportunity!” he said. “I’m sick of hearing about it!”

Does this mean that Treasure Island will truly become the Ecotopia that we’ve all been waiting for? Shareable.net teamed up with the nonprofit news site Public Press and the crowdfunding journalism project Spot.us to dig beneath the Treasure Island’s Ecotopian image. Here’s what we found:

- “The public thinks we’re going to build a city in the public’s interest,” says Charles Marsteller, a former coordinator of San Francisco Common Cause. “I would say we’re building a city in the private sector’s interest — and whatever they want, we’re getting. Ultimately the residents have to live with the consequences long after the developer is gone.” In their report, Shareable.net contributing editor Bernice Yeung and journalist Alison Hawkes document how developers like Miami-based homebuilder Lennar courted politicians to push the project forward. For example, when voters passed a referendum to limit the mayor’s authority over Treasure Island, it was never fully implemented.

- As Christopher Cook reports, Lennar suffered especially deep wounds from a home-mortgage crisis that it and other builders helped fuel through speculative over-building and their widespread issuing of subprime loans through subsidiary underwriting firms. Then, in a calculated bid to shore up its balance sheet, Lennar turned to Congress, the tax code, bank regulators, and high-risk debt for financial salvation. When Cook contacted Lennar for a comment, Lennar's spokesman replied, “Thank you for the invitation but we do not offer comments on the subjects which you request.”

- Speaking of the mortgage crisis, the Treasure Island redevelopment is being financed by a byzantine range of financial instruments — based on assumptions that could turn out to be horribly wrong: The city might not get all the property transferred from the U.S. Navy on schedule, slowing down construction; the costs of preparing the infrastructure might rise due to unforeseen challenges; and developers don’t know what prices they can charge for the land, once it has been prepared, because of fluctuating market conditions. If any one of these assumptions is proven wrong, it could derail parts of the redevelopment’s Ecotopian vision.

- Most of Treasure Island will be inundated by the end of this century, if the documented progression of the ocean’s rise caused by climate change continues as predicted, suggests Victoria Schlesinger’s investigation. Studies foresee sea-level rise ranging from as little as five inches to as much as six feet. The lowest parts of Treasure Island lie just four feet above the Bay’s low tide. Worse, Treasure Island is a former Navy base, which means that it was a toxic waste dump for decades. Many Treasure Island sites have been decontaminated through soil removal or capping, which entails covering the remaining toxic soil with a clay cap. But there is growing concern that coastal sites once considered sufficiently remediated may become problematic as sea levels rise. As the sea pushes contaminated soil higher, it could come in contact with ground water.

- Then there is the issue faced by every California building project: earthquakes. Treasure Island was constructed in the 1930s out of sand and silt dredged from the Bay and held in place with a riprap retaining wall. When loose water-saturated soil is shaken intensely, it turns into a thick, unstable liquid, a process called liquefaction. “The [new] buildings should structurally perform well on such soil assuming they are built to code,” says Thomas Holzer, a U.S. Geological Survey research geologist who studied Treasure Island following the 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake. “The untreated open space area could be pretty exciting in a large earthquake with water and sand spouting out of the ground.”

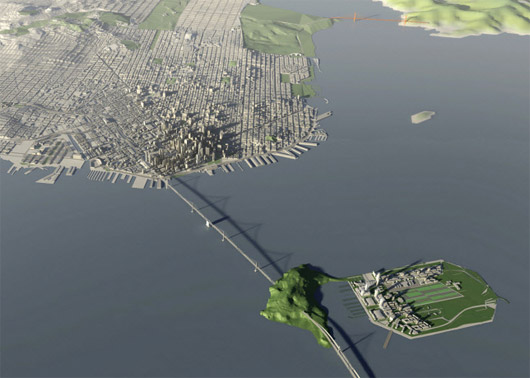

If sea levels rose 2.25 meters, much of San Francisco would drown, and Treasure Island would almost disappear. Source: Architecture 2030.

If sea levels rose 2.25 meters, much of San Francisco would drown, and Treasure Island would almost disappear. Source: Architecture 2030.

Alternative Visions

In short, while the master plan is something many of us can believe in, our hopes shouldn’t cause us to overlook the factors that may turn Treasure Island into a disaster area — and here is where I must repeat those grim, clichéd words about the road to hell being paved with good intentions. If we are in full possession of the facts, it is not difficult to look ahead 30 years in the future and see the sustainable towers of the master plan broken by quakes, flooded by the sea, and decimated by another mortgage crisis. Instead of Callenbach’s Ecotopia, Treasure Island might look like J.G. Ballard’s The Drowned World.

Does that mean Treasure Island should be abandoned?

Some people certainly think so. Aaron Peskin, former president of the San Francisco Board of Supervisors, calls Treasure Island “a blob of Jell-O in the Bay,” adding: “The best thing is to let natural processes do its thing, and allow it to return to that which it came.” Instead of looking to blank slates like Treasure Island on which to build an Ecotopia, goes this line of thinking, San Francisco should retrofit itself for social and environmental sustainability.

Even if the city and developers go forward with the plan, the problems that plagued Stevenage persist — we still see the people with the power and the money pitted against the people most affected by elite decisions. “Redevelopment in San Francisco has a bad reputation going to back to the ’60s,” says Chris Carlsson, Shareable.net contributor, lead instigator of the Critical Mass bike ride, and author of the 2008 book Nowtopia. “Without the strong public support, they don’t get permission to do it.” Indeed, the more one learns about the stake lobbyists and developers have in Treasure Island, the more one wonders if the Ecotopian vision isn’t just a way to sell development to a skeptical, but progressive, public.

“The problem with master planning is that it’s a fantasy that you can engineer a good social life and sustainable living through architecture and design,” says Carlsson. And building a new city in the middle of the Bay is far from carbon neutral; two decades of construction will inevitably have a massive impact on the Bay’s ecology. It would be far better, Carlsson argues, for the island to become a laboratory and educational resource dedicated to “reintegrating the Bay as a food source and ecological resource for the community, not just something pretty to look at.”

Architect, social entrepreneur, and Shareable.net contributing editor Stephanie Smith goes even further. Plans like the one for Treasure Island “would be fantastic if they were half-finished,” says Smith. “I prefer that it not get finished.” Instead of a master plan, she imagines a complex process of settlement that is, on one hand, more consistent with how cities were founded in the past but is, on the other hand, a radical break with modern planning, architecture, and development: In her alternative scenario, architects and planners would provide a “half-done” framework that that would be refined by people who moved there to live in temporary shelters and work to complete the development over many years.

Shades of Smith’s Cul-de-Sac Commune project, which sought to retrofit existing suburban enclaves as communes through a process of collaboration among residents, she suggests that the settlers (for that’s really what they would be) brainstorm their community’s design over many years and physically participate in building it. “Resource sharing” — as opposed to master planning — is the basis for this design. The main goal of the process is not sustainability; it’s community. Sustainability is just a byproduct.

“The process of creating their own environment would solidify [residents] as a community,” says Smith. “We can’t expect instant community, because community is really tough to build. So how do you get that? You gotta go through something together. Community isn’t touchy feely; it’s transactional.”

Treasure Island’s master plan, she argues, “invokes the idea of community, but they don’t build in ways to foster it.” From Smith’s perspective, the world we live in has been shaped by multi-decade process of community decay in the United States, whose damage we are only just starting to undo. “We’ve been talking about green for fifteen years now, but we’ve just started talking about rebuilding community,” says Smith.

So does the master-planned nature of the Treasure Island redevelopment mean that shareable community is beyond its reach?

Chris Carlsson emphasizes that even the most flawed development can be transformed by the people who live there. “I can imagine in 25 years people taking it back from the planners and turning it into a funky space where people live,” he says. Ernest Callenbach, ever hopeful, makes a similar point, choosing to see Treasure Island as a process and an opportunity. "It's rare for a city to get the chance at spinning off a better self,” he says. “Mitosis happens in biology. Now let's see if San Francisco can do it in ordinary life!”

Linda Shipman is a member of the Community Advisory Board for the Treasure Island project and an advocate for formerly homeless and low-income residents. Credit: Monica Jensen

Linda Shipman is a member of the Community Advisory Board for the Treasure Island project and an advocate for formerly homeless and low-income residents. Credit: Monica Jensen

Smith, Carlsson, and Callenbach probably sound crazily idealistic to some observers — and yet Smith is merely describing the way cities have been founded for most of human history, and all their ideas are (surprisingly?) consistent with empirical studies of ideals in action. “Must utopia, realized, always disappoint?” asks Harold Orlans at the end of Utopia Ltd. He does not dismiss the utopian impulse, which we might just define as a belief that the future might, with effort, evolve into something better than the present. Instead he concludes:

To be persuasive and practical (to persuade different kinds of people and to be practiced in different times and places) a utopian idea must be relatively simple and generalized. But life is more complicated than a single idea, and probably than any idea or image.

This echoes Smith’s description of utopia as a point of departure, not a master plan — a forum for many voices and a conduit for resource sharing, not an ideal handed down from on high. Redevelopments like the one on Treasure Island will naturally arise from many competing interests — the trick, as is so often the case in our society, is to limit the power of developers and politicians while amplifying the voices of the people who will be most affected.

Unfortunately, as in the case of Stevenage fifty years ago, open-source planning usually means that abstract plans for perfect cities on the hill are never fully implemented. In Shareable.net, South Florida planner Daniel DeLisi writes:

I’ve discovered that the open, shareable nature of the planning processes I try to facilitate means that my highest ideals are rarely realized. I am an environmentalist who has helped build gas stations and malls. I have experienced defeats as well as victories, and I’ve helped forge compromises that would have horrified the young environmentalist that I was before entering MIT. In the end, however, I’ve helped build better, less destructive gas stations and malls, and I’d like to think I’ve helped the stakeholders understand each other just a little more.

To the fiercest utopians, DeLisi’s mature perspective will seem dreary, soft, and compromised — but it is nonetheless true that any real-world eco-city will emerge from a process of argument between those who pursue uncompromising ideals and those who pursue self-interest, as well as ordinary folks who just want a nice place to live and work. Facilitators like DeLisi play an essential role in any collaborative planning process.

In the end, the most important thing we can do is watchdog redevelopments like Treasure Island as they unfold, and try to hold developers and city officials to their promises — indeed, that’s why we launched our research into Treasure Island. From this perspective, Treasure Island stands to become a battleground, not utopia. This shouldn’t surprise us.

The word “utopia” is a Greek pun that simultaneously means “perfect place” and “no place,” suggesting that perfection is impossible. But the meaning of “ecotopia” is quite different: “eco” means home, and “ecotopia” is simply a human habitat. Treasure Island will never be utopia, but the plan does give some of us an ideal worth fighting for.

This essay is based on our collaboration with the nonprofit news site Public Press and the crowdfunding journalism project Spot.us to dig beneath the Treasure Island’s Ecotopian image. Reporters interviewed the developers, city officials and architects, and pored over documents about the nuts and bolts of financing, development and environmental remediation. They also examined the city’s green planning schemes and proclamations about cutting-edge community building. To learn more, please read the original articles, which were first published on June 22 in the pilot print edition of Public Press:

- Can Treasure Island realize its ecotopian dream?, by Jeremy Adam Smith

- Homebuilder Lennar uses federal taxpayer funds to balance its books, by Christopher D. Cook

- Treasure Island timeline, by Jerold Chinn Treasure

- Island residents face choices for relocation, by Katy Gathright

- Financial upside for developers is long-term and risky, city says, by Victoria Schlesinger

- Through two mayors, connected island developers cultivated profitable deal, by Alison Hawkes and Bernice Yeung

- Pollution: experts concerned about Treasure Island cleanup as seas rise, by Victoria Schlesinger

- Uncertain about rising seas, developers using mid-range estimate to build up island, by Victoria Schlesinger

In October, 2010, the Society of Professional Journalists Northern California chapter selected this investigation for an Excellence in Explanatory Journalism award.