Investors purchase stocks or bonds with the expectation of future financial rewards.

Yet systemic racism and inequity in financial markets have blocked many working-class communities of color from building wealth of their own.

The Boston Ujima Fund aims to change all that, by building a movement that reinvests into the neighborhoods and dreams of communities, families, and people who have experienced generations of this sort of financial discrimination.

Social and cultural ROI

For Joyce Clark, a research program coordinator living in Boston, her initial inquiries at her bank about investing in stocks were “uncomfortable.”

“Right away,” she said, “they were putting up barriers without knowing who I am or what I have.”

As a newcomer to investing, she was full of questions, but she said her bank’s representative only cared about how much money she could bring to the table.

Ujima, in contrast, was more concerned with what sort of social change Clark wanted to see as a result from her investment.

“Unlike the banks I visited, they didn’t ask for money,” Clark said. “It’s not often you get a chance to be a part of change, and it’s very humbling to see my money really make a difference.”

Denisha McDonald, a real estate social-impact consultant, said that while her investments might get a higher financial return in traditional financial markets, Ujima is more rewarding, because her return on investment (also known as her ROI) happens on multiple levels.

“I not only see an ROI financially, but I also see the ROI socially and culturally,” she said.

Investing — in reparations

Both Clark and McDonald invest in the Kujichagulia pool, one of three such investment pools Ujima maintains.

Nia Evans, executive director of the Boston Ujima Fund, refers to Kujichagulia as a low-barrier, wealth-building vehicle because the minimum deposit is $50.00. The pool is open to working-class people of color who live in Massachusetts.

“The Kujichagulia pool will return the most, and that’s intentional. It’s our way of redefining risk,” Evans said, describing the fund as a community-led reparations initiative to empower those who have been routinely denied access to economic opportunities, job markets, and other wealth-building initiatives.

Evans says Kujichagulia investors also have their risks limited — an intentional strategy to protect a group of investors who have less financial resilience.

In addition to Kujichagulia, Ujima also provides three other investment pools — the Umoja Fund, the Nia pool, and the Imani gift pool.

The Umoja Fund is designed for a more diverse population of investors, including businesses and stakeholders located in Massachusetts, Maine, Connecticut, Rhode Island, and New York. Accredited investors may also purchase a Umoja note. The minimum investment is $1,000 and the maximum is $250,000.

The Nia pool requires a minimum contribution of $5,000 and is primarily slated for large institutions, philanthropic foundations, and wealthy individuals.

The Imani gift pool is a reserve used to cover investment losses, starting with Kujichagulia investors, who, earlier this year, got their first return of 3 percent.

The returns on Kujichagulia, Umoja, and Nia investments are, respectively, 3 percent, 2 percent, and 1.5 percent

Creating alternative economies

Economic racism is a real issue that denies people the opportunity to support themselves and their families, start businesses, or build financial legacies — such as homeownership — that pass from one generation to the next.

According to “The Color of Wealth in Boston,” a joint publication by Duke University and the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston, the wealth gap in the United States is widening, and affects “millions of families nationwide” who lack assets that would otherwise provide “better opportunities for future generations.”

The statistics cited in the report are daunting.

- White households in the United States have a median wealth of $247,500, while Dominicans and Black households have a median wealth “of close to zero.”

- Almost 80 percent of white people own a home, compared to only one-third of all Black people, less than one-fifth of Dominicans and Puerto Ricans, and only half of Caribbean Blacks.

- 56 percent of white households have retirement accounts, compared to just one-fifth of U.S and Caribbean Blacks, and 8 percent of Dominicans, have them.

To address these inequities, Ujima does not rely on or appeal to the institutions that have historically stood between Blacks, and other people of color, and progress.

Instead, according to Evans, the Fund organizes and rallies working-class communities of color living in Boston to “be their own change,” and has raised an impressive $3.2 million toward its 2021 goal of $5 million.

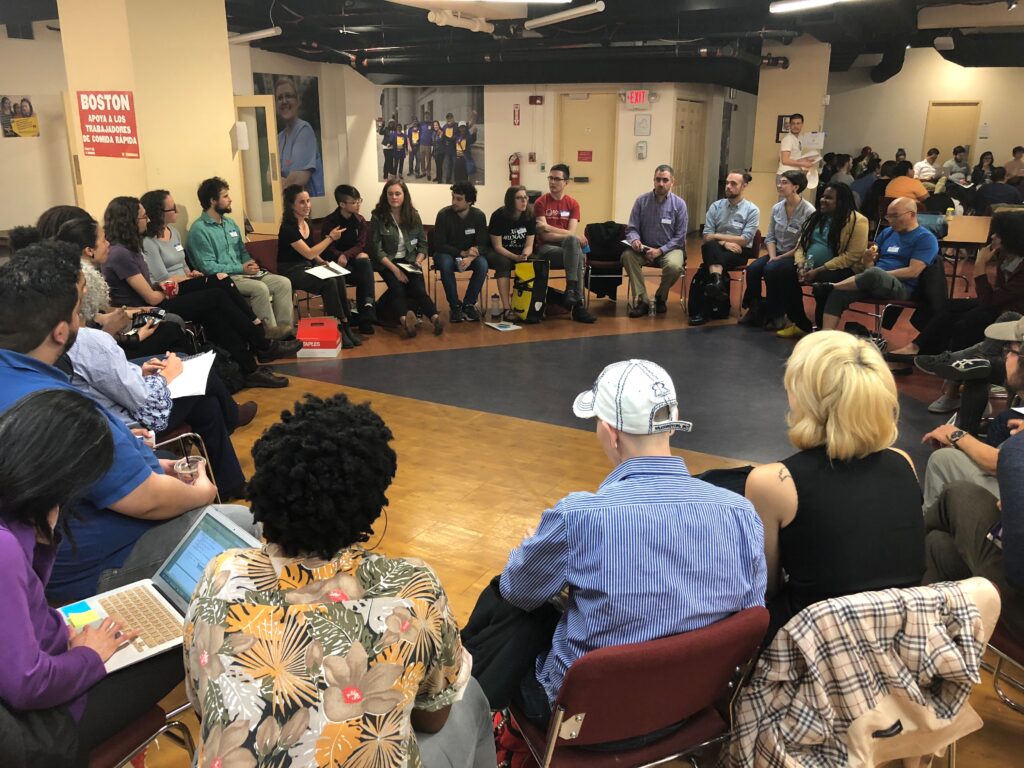

Networking collective community economics

In 2015, Boston Ujima Fund co-founder Aaron Tanaka conceived of an accessible, inclusive ecosystem for working-class communities of color living in Boston. He partnered with Evans and a host of other co-founders, and the Boston Ujima Fund was formally launched in 2017.

Beyond investing, other Ujima-related projects include improving institutional accountability in Boston; using arts and cultural events to organize people to support the Ujima network; offering alternative currencies, such as customer reward cards for frequenting businesses that support working-class consumers of color in Boston; and ensuring that businesses operate equitably and fairly.

The project bases its ideologies on the seven Kwanzaa principles, which are inspired by African cultural practices that build and reinforce community.

The principles of Umoja (unity), Kujichagulia (self-determination), Nia (purpose), Imani (faith), Kuumba (creativity), Ujamma (cooperative economics), and Ujima (collective work and responsibility) were derived from the Swahili language, spoken in East African countries, such as Kenya, Uganda, Tanzania, Rwanda, Burundi, and South Sudan.

As a place-based fund, Ujima is reminiscent of Pan Africanist Marcus Garvey’s Black Star Line, a steamship corporation established in 1919 to help average Blacks and everyday investors to build a future on their own.

“A race that is solely dependent upon another for its economic existence sooner or later dies,” Garvey said.

Now, the success of the Boston Ujima Fund is inspiring a movement around the United States.

“We get a lot of people from different communities asking how they could do a Ujima where they are,” Evans said. “So we’re actually mentoring groups in Atlanta, Cleveland, Los Angeles, and Chattanooga, Tennessee.”

She goes on to note that “Ujima works in Boston because of its unique set of laws, organizing processes, and other variables. Those may be different, and therefore create a different outcome in other places.”