Two new TSRC reports analyze survey data from Zipcar for Universities and car2go. (Christopher Schmidt / Flickr)

Two new reports from the Transportation Sustainability Research Center at UC Berkeley confirm the positive social and environmental impacts of carsharing, even among special populations—such as college faculty, staff, and students—and within one-way carsharing systems. At the same time, the two survey-based studies are important reminders that context matters when it comes to the magnitude of these impacts, with net reductions in vehicle ownership and vehicle miles traveled varying according to location, member background, and system type.

North American College/University Market Carsharing Impacts: Results from Zipcar’s College Travel Study 2015 documents the relationship between membership in Zipcar and vehicle use and ownership, travel behavior, quality of life, and environmental effects within a specific subset of the company’s clientele: faculty, staff, and student members of Zipcar for Universities. Compared to conventional, neighborhood-based systems, campus-based carsharing networks have received scant attention from researchers. College carsharing members differ from their neighborhood-based peers in several important ways, including household composition, which the TSRC study’s authors took pains to take into consideration.

This year, we’ve seen Mutual Aid in Motion.

From scaling sharing hubs to Mutual Aid 101 trainings, we’re helping communities build the tools they need.

Every dollar fuels lasting resilience – proving that when we move together, we all move forward.

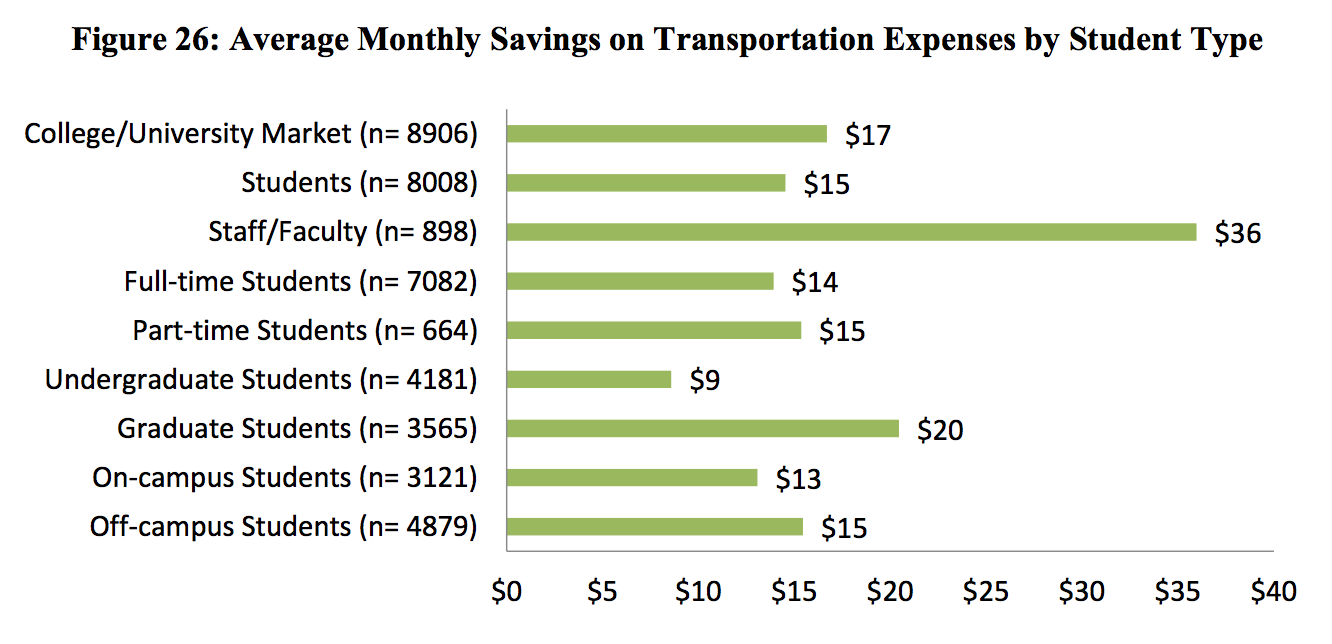

According to the study, campus-based carsharing delivers net benefits similar to those observed in neighborhood-based programs. A November 2015 survey of North American Zipcar members, combined with usage data, evidenced an average monthly savings in transportation costs of $17. Moreover, the Zipcar for Universities scheme appears to have had a small but significant suppression and shedding effects (i.e. members avoid purchasing new vehicles or sell existing vehicles because they belong to a carsharing network). The total estimated reduction in vehicle miles traveled and greenhouse gas emissions due to suppression and shedding outweighed any extra driving by college/university members, despite the fact that the former impacts applied to a tiny minority of users. The researchers observed that the suppression to shedding ratio was higher on college campuses than within neighborhood markets, likely because students, in particular, have unique driving habits and/or may factor in carsharing prior to deciding whether or not to bring a vehicle to school in the first place.

Zipcar for Universities members saved an average of $17/month on transportation costs. (North American College/University Market Carsharing Impacts)

The second study, Impacts of Car2go on Vehicle Ownership, Modal Shift, Vehicle Miles Traveled, and Greenhouse Gas Emissions: An Analysis of Five North American Cities is built around survey data from the one-way carsharing service car2go. Unlike in two-way programs (including Zipcar), one-way carsharing members can pick up or drop off shared vehicles anywhere within prescribed zones. Users benefit from increased flexibility, but observers have questioned the potential of such systems to raise vehicle miles traveled and greenhouse gas emissions by way of encouraging trips that might otherwise have been made using public transit, on foot or on bike, or skipped altogether.

As in TSRC’s Zipcar for Universities report, the car2go paper suggests that the suppression and shedding effects of one-way carsharing services outweighs the increase in trip frequency encouraged by the more flexible model. Other impacts varied according to users’ geographical location. The effect of a car2go membership on drivers’ use of other transportation modes, for instance, differed from city to city. That said, certain patterns emerged: car2go members tended to substitute one-way carsharing trips for public transit and, especially, taxis, but also walked more after enrolling in the program.

Like TSRC’s previous publications on carsharing, these two reports offer important insights into the behavioral and environmental effects of the rapidly-evolving field. Given their targeted focus, the studies necessarily omit certain crucial questions, including the capacity of carsharing to address the mobility equity gap. Nevertheless, their most prominent takeaway—that carsharing represents one path to reduced vehicle ownership and vehicle miles traveled, even among student users and within one-way systems—affirms advocates’ commitment to growing both the practice and the study of this and other shared transportation modes.

The car2go study documented small but significant suppression and shedding effects. (Impacts of Car2go on Vehicle Ownership, Modal Shift, Vehicle Miles Traveled, and Greenhouse Gas Emissions)