This piece originally appeared in io9: We Come from the Future. We're republishing it under Creative Commons because we think it goes really well with our essay on San Francisco's Treasure Island redevelopment, "Can a City Build a Better Version of Itself?"

Before he invented the safety razor, King Camp Gillette was a futurist. In 1894, he published plans for a porcelain, hexagonal city with transparent sidewalks. Why do so many innovators dream of building the perfect city?

I've been thinking about that question a lot since seeing Christopher Nolan's new film Inception, which is in part about an architect who gets work designing collaborative dream spaces. Inception's citiscapes are places where people hide secrets and memories, but they are also vast mazes – puzzles to be solved.

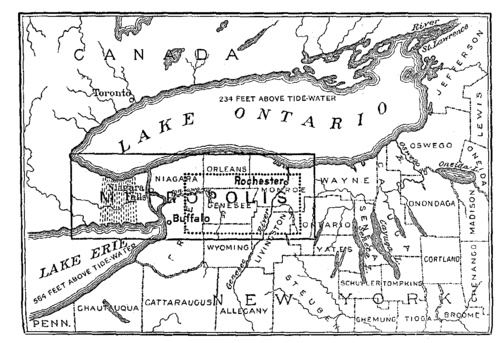

Gillette wanted to solve the problem of social inequality with his perfect city, which he named Metropolis. The city, which he outlines in his book The Human Drift, would be built on top of Niagara Falls. Gillette wanted to Nikola Tesla design a water-powered electrical grid, which would be amply supplied with energy from the falls.

The sidewalks of the city would be transparent so that workers laboring beneath the buildings, dealing with plumbing and other infrastructure, would have light. But Gillette also wanted the city's residents to see the people at work below their feet. The idea was to prevent people from forgetting about all the essential work that goes into making a city run.

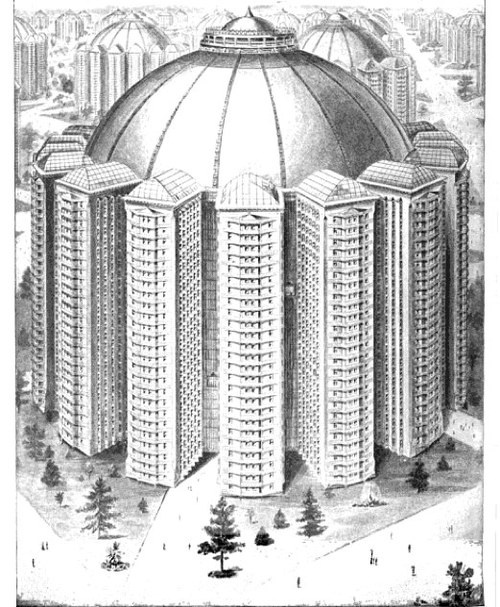

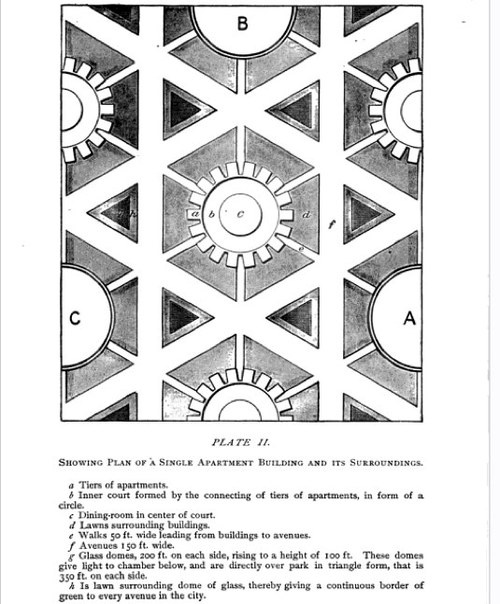

Gillette laid his city out in a hexagonal grid that would accommodate the many vast, perfectly round buildings where people lived, worked, and indulged in recreation. In the image below, you can see how he planned to distribute buildings of different functions evenly throughout the city. He writes, "This small section shown in the plate contains thirty three apartment buildings: five educational buildings marked A, five amusement buildings marked B, and five buildings where food is stored and prepared marked C."

But the perfectly even distribution of everything didn't stop there. Every residential building would offer its residents the same amenities, including lovely rooftop gardens. From there, they could look down on a city free of all vehicles save "rubber-tired electrical carriages and bicycles."

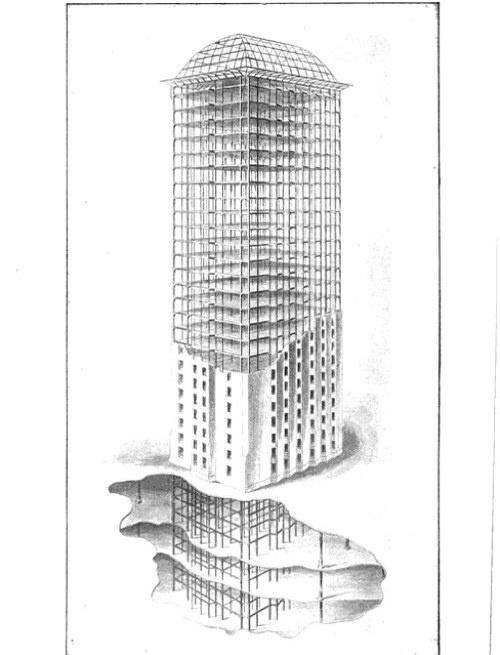

I am particularly fond of the generous floor plans Gillette created for each apartment in his gigantic round buildings. He was especially concerned that each apartment have big windows.

What secret was Gillette hoping to find in the perfectly round buildings of his Metropolis? How to foster human progress while also keeping everybody productive. In fact, Metropolis was just an expression of his overarching desire to structure human society so that science and innovation would blossom. It's worth quoting him at length on this point:

It is my firm belief that under conditions of material equality, all necessary labor could be forwarded without friction; that a system of compensation to balance supply and demand for labor, carried out on plan proposed, could be reduced to an exact science, and humanity would march along the highway of progress without any disturbing elements to check its advance. The business of production and distribution, which now demands at least ninety per cent. of all the brain power of the world, and is almost the sole subject of conversation between individuals, and, either awake or sleeping, draws upon the mind's vitality, would no longer occupy the attention of the people. The whole channel of conversation and thought would be turned, as if by magic, into the field of scientific research and improvement in invention and devices for production that would save manual labor and increase the quantity and quality of products. Thus the world would gain what is now an enormous waste of brain power, which would be devoted to the field of progress in science, art, and invention; and our rapid advance to a higher ideal would be in proportion to this gain. The thoughts and conversation would no longer turn to wealth and production, for production and distribution would be mechanical, based on our progressive position; and to advance this progressive position would be the field of competition, and demand all thought and conversation.

Above, you can see Gillette's schematic of human society – "the human drift" – laid out with as much care as his city plans. He imagined a corporation called the United Company, whose stocks would belong to everyone, and which would help coordinate the world's industry.

So how do you get from dreaming up equalitarian cities to inventing the safety razor? Like Metropolis, the safety razor is an elegant invention. But it's the opposite of Gillette's city in so many ways: Modest and ordinary, the safety razor isn't built from futuristic, transparent materials. And it hardly revolutionized science.

What it did do, undoubtedly, was change the everyday lives of ordinary people. It made life easier, in a small but meaningful way. Perhaps Gillette finally figured out that if you can't rebuild society to make people's lives more comfortable, at least you can make shaving less of a chore. The safety razor is exactly the kind of thing you'd expect Metropolis' citizens to stock in their bathrooms (with electric lights!), in those lovely apartments overlooking the falls.

If you can't make your dreams of Utopia real, at least you can import a few small objects from that dreamworld into ours. And that's just what Gillette did. Ultimately the scifi entrepreneurialism of The Human Drift paid off for him in real-world money. The Gillette razor empire made him very rich.

Gillette first hatched his wild ideas for a city through his association with a group called the Twentieth Century Society. The group, ironically, did not actually last into the era that was its namesake. It seems that Gillette's life was full of detailed plans that never came to fruition: Plans for the twentieth century, plans for cities, and plans for vast corporations.

But I would argue that Gillette's detailed vision for Metropolis did serve a useful function. Which brings me back to Inception, where our antiheroes use imaginary citiscapes to plant an idea in the mind of a person who believes he is dreaming. Why a city? Why not a vast countryside, or outer space? Because cities are one of the only physical embodiments of human ideas about humanity. Cities are ideas made concrete – their walls and promenades describe a whole civilization's ideas about where people should live, what kind of entertainments they should pursue, and how they should perambulate from one location to another.

Dead societies leave their cities behind like cultural skeletons. And living, vital societies are always in the process of producing cities for the future. Cities that will change how we live, or how we get from place to place. We dream cities because we dream of rebuilding our civilizations.

We dream cities, but in the end perhaps we make safety razors. I'm still not sure if that's a bad thing or a good one.