Monopoly is a game of ruthless competition. A grueling three hour marathon of Scotty dogs imprisoned, beauty contests won, hotels built and railroad utilities consolidated, Monopoly is simultaneously one of America’s most beloved and most hated board games. Monopoly is such an iconic part of American culture that when it got rid of its iron piece and replaced it with a cat earlier this month, it made national news.

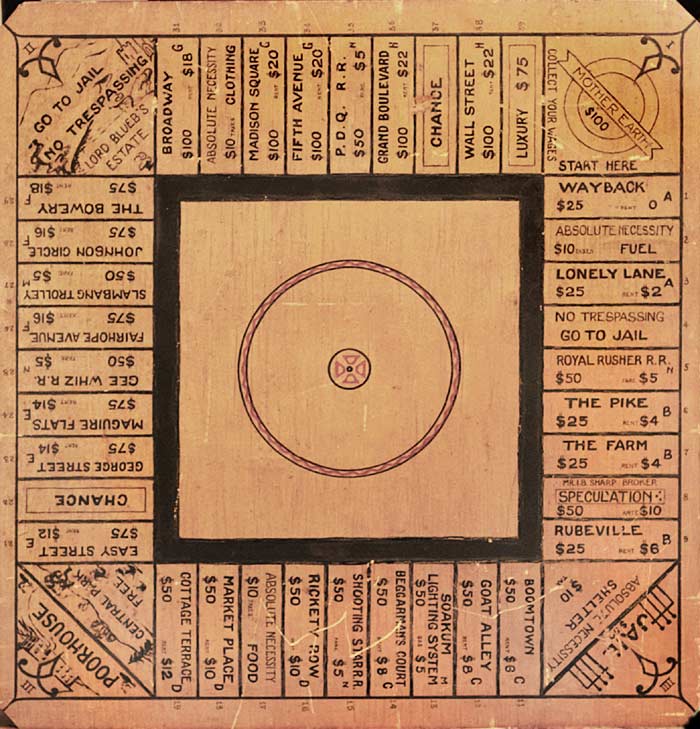

But Monopoly wasn’t actually designed to encourage ruthless cut-throat land grabs. Instead, the game was envisioned as a teaching tool about the injustice of landlords, one whose in-built ruthlessness would demonstrate the dangers of such practice. Called “The Landlord’s Game” when it was first invented by Lizzie Magie, in 1903, the game was in many ways similar to how it is played now.

But recently a remarkable rediscovery has been made: Magie designed advanced rules into the game which were made to demonstrate that everyone could live in harmony and sharing. They were never included in the Parker Brothers version, but, in all the early boxes, you were given an address to send to Magie for her advanced rules. If you did, under the heading of “For Advanced and Scientific Players”, Magie suggested a way to play where, rather than one person owning everything, all the players could share in the wealth.

Magie was a Georgist. The Georgists believed that people should be able to hold onto what they create with their own efforts, but that all things “found in nature”, especially land, are owned by all. For the Georgists, landlords were the root of all injustice, and they argued for a single progressive land value tax, to replace all other forms of taxation. This, they argued, since it would only tax wealth, could bring about equality and justice, and also break down the hegemony of the landlords.

If Magie’s rules don’t look very familiar to Monopoly players, they might look familiar to partisans of the solidarity economy. For example, all rent (when you land on a square) is paid into the central treasury of the game, rather than an individual- after a certain amount of money is collected from land taxes, the railroad and utilities are automatically purchased, making them free if you land on them. Similarly, the land tax will eventually build free colleges. You can buy properties anywhere, but you can’t really profit off of them. It’s a strange modification.

Of course, Magie’s didactic game play probably wouldn’t be that much fun in the end—perhaps the reason her rules never took off. But when it comes to actual life, outside of the game board, the ideas Magie put forward — free utilities, free education, shared resources, communal production of wealth — make a lot of sense. If we could keep playing Monopoly as a competitive game, but live in the world of justice and equity Magie imagined, we’d be much better off indeed.

You can check out Magie's special rules here.