+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

Please share with Shareable! Click here to support our coverage of the real sharing economy.

Africa had at least 492 separate kingdoms before the Europeans showed up. Some of these kingdoms were mobile, moving between different areas based on the season. There was no such thing as a "nation state" or a permanent border. Such concepts were foreign and were imposed on Africans by European colonists in order to better administer (i.e. exploit) the "unruly" lands. The colonists sliced up the continent into "manageable" chunks that could be divided amongst the powers fairly. Naturally, no Africans had any say in the matter.

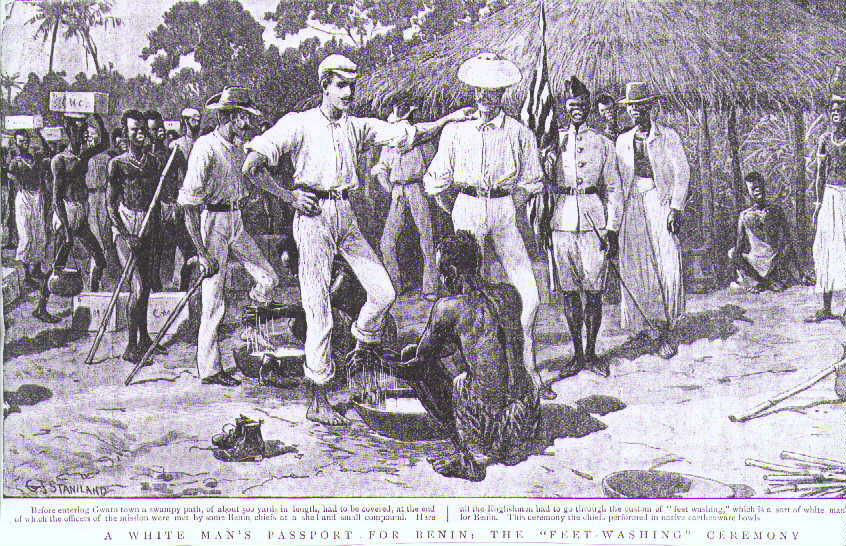

In 1870, about 10% of Africa was under European control. By 1914, it was up to 90% of the continent. The intervening period was called the Scramble for Africa, and it involved most of Europe's major players in a race to carve out lucrative territories for themselves.

After two world wars and the collapse of several regimes, many powers lost their hold on these colonies. Some colonies, on the other hand, revolted violently to regain their independence from the colonizers who were reluctant to let go of their overseas holdings.

There is another "Scramble for Africa" going on at this very moment, but it's not for land, it's for bandwidth: only one third of the planet is connected to the internet and there's a rush to connect the rest of the world's population. Yet the "digital divide" has become a chasm, and instead of building infrastructure, which would be very costly since there is very little infrastructure in Africa to begin with, there are some "quick fixes" being considered by Western multinational corporations.

You've probably been hearing a lot in the news about the attempts of Google and Facebook to get Africa online. Ever since industry experts like Mckinsey began publishing market data on the earnings potential Africa presents, they've been falling all over themselves to get a foothold in the continent.

These internet giants want to get into Africa with "an" internet before anyone else does but not necessarily with "the" Internet that we know, but a cheaper, slightly watered down version that sounds really cool, but is it?

In Google's case there's the Loon Project, using balloons to give internet access to rural villages. They put balloons into the stratosphere and create an airborn mesh network out of these devices to cover a specific area. The only physical danger is that sometimes they come crashing down.

Facebook, on the other hand, has their CEO selling us on the idea that an increased terrestrial cell phone network with added data coverage and an app will be able to extend Facebook deep into places that even Kira Salak couldn't get to. They are already into Kenya, their third African country so far. It's not a bad idea considering that internet access via smartphones outnumbers other devices 30:1. But have you ever tried to write anything substantial on a smartphone?

Beyond that there's reports of Facebook's drone invasion to connect really far out areas that are beyond cell towers. Maybe the drones will shoot down the Google balloons to gain a competitive advantage over Google, as this news animation humorously demonstrates.

Some experts fear that the internet that these corporations are creating in Africa will have no net neutrality "built in," so as not to repeat the mistakes made in the US because net neutrality doesn't benefit multinationals.

The version of the internet that these large companies are actually proposing is often a cached and restricted version; the equivalent of selling America's old reruns to the developing world. They are seeking to replicate the (highly profitable) one-to-many broadcast model of the television instead of an internet that lets people connect with one another to create communities of value.

It's true that every day that passes without access to internet is a day you're left further behind the "connected" world, but what does that mean? A recent study examined what it's like for people to use the internet for the first time and it claims they lack the "mental model" to even approach the internet as a concept. This sounds like a dream demographic for advertisers; they can make it up as they go along and no one will be the wiser. Or will they?

When the internet is used to empower people, it can be an emancipatory force, but if it's used to simply turn an entire continent into a prospective revenue stream of Netflix subscribers, then it doesn't appear much different than what was going on in the 19th century.

There are, thankfully, some much smaller and promising initiatives with long term goals which are trying to build community and educate users rather than simply exploit a potential gold mine of data.

The Kibera Mesh Network recently announced plans to construct a wireless community in Nairobi, Kenya. Their approach will enable inhabitants to learn about how the internet works as well as teach them valuable skills that they can pass onto others in their village.

Kibera is not the first of the "internet missionaries" speaking the gospel of Open Source in Africa. In 2012, a project to create a self-sufficient mesh network using Commotion's free and Open Source software was started in Somaliland. The network was created by residents of the village to be a self-sustaining network which the residents learned how to build and manage from project coordinators.

Similarly, Freifunk has created a free and downloadable manual for people to create their own mesh networks from start to finish. People who learn how to network can teach others how to network too.

More projects like the Mesh Potato have found their way to Africa as well, bringing low cost VoIP to people who need it and also data connectivity.

But the most well-known project is the Outernet, which has changed shape several times over the last few months, originally appearing to be a network of cubesats circling the earth and finally emerging as the Lantern, an autonomous library able to receive (but not transmit) data from any spot on the globe. Their goal is put a "library in every pocket."

Shareable readers know all about mobile libraries, but this is something new, this is something truly global. An innovative approach to disseminating information. But the question remains, which information will be available?

With competition from Google and Facebook, these projects might have difficulty getting off the ground, especially since these multinationals are mostly targeting the same countries where these smaller projects are already operating. In a world where we want everything faster, easier and cheaper, how do you convince someone in Africa that a solar powered data receiver will, in the long run, be more liberating than a shiny flying drone? For that matter, how do you convince a westerner?