This story was originally published at re:form, a new design publication on Medium. Illustrations by Susie Cagle.

The first time I rode my bike from my new house in Oakland, I felt hopeful.

I sped down the smooth hill, clad in new bike gloves and helmet, official city bike map in my front pants pocket.

By the time I arrived downtown, less than three miles away, I’d dodged five very close-cutting cars, a half-dozen errant pedestrians, and more potholes than I could count.

I’d gone exactly where that map had told me to go: on busy, skinny, two-lane roads, and into unpaved, gravely shoulders. The map almost got me killed.

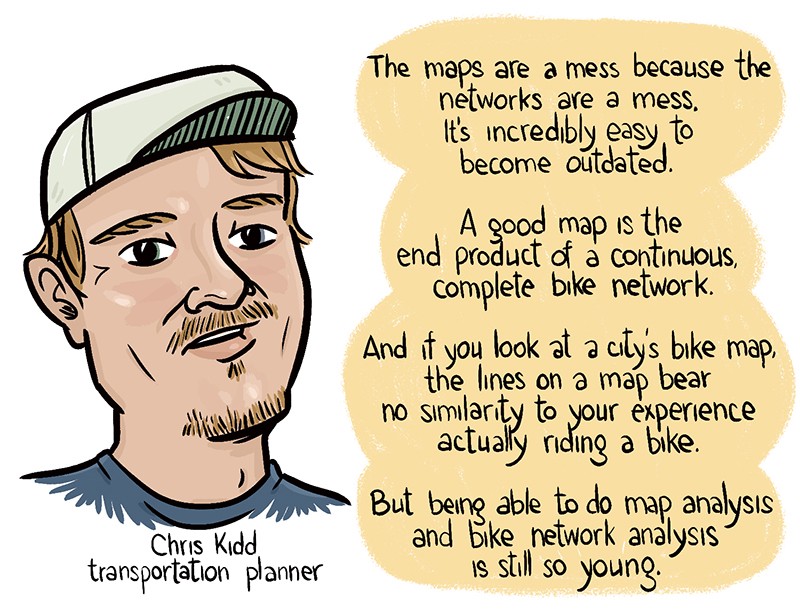

When I told this to Chris Kidd, a senior planner at Alta Planning and Design who often works on bicycle infrastructure and mapping, he shrugged, and smiled: “That’s not surprising.”

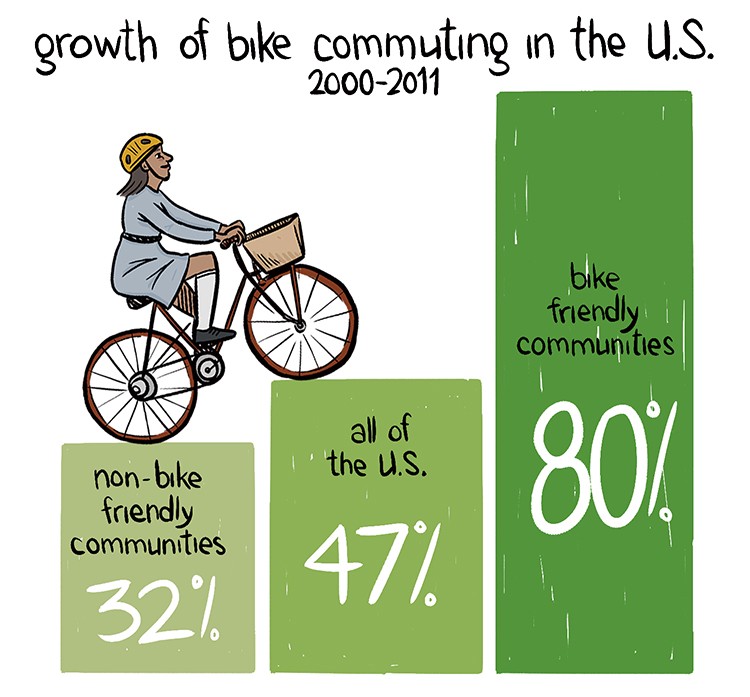

Cycling is up across the U.S. in recent years as more people are seeking healthier, cheaper ways to commute — and as bicycle infrastructure grows more robust, people are looking for easier, more accurate ways to map and predict their commutes.

But bikeway system maps are deeply broken, just like the networks they attempt to track. The problem has created both challenges and opportunities for cities, cyclists, planners, and tech companies alike.

Would-be bike-riders respond to surveys with incredible consistency: The greatest obstacle to getting more cyclists on the road is a perceived lack of safety and comfort.

America’s massive road infrastructure might have been built with cars in mind, but it has tremendous capacity to be lightly retrofitted for cyclist comfort and safety. For now, though, that’s more potential than it is reality. Even in places with robust cyclist legions and bike lanes, the infrastructure is incomplete, if not outright confused. Some bike networks appear to have existential crises mid-block, disappearing and reappearing a tenth of a mile down the road without explanation.

Unlike our roads themselves, this infrastructure is constantly developing and changing. And that’s good news, on the whole. But as cities are expanding their piecemeal bike networks, many are neglecting to update their internal data and their public maps.

People feel safer riding on protected bike tracks — but what if you build it and they don’t come, because no one knew it was there? What if this isn’t a transportation or an infrastructure problem, but a design problem?

For several years, open-source mapping advocates have worked to try to fill this gap. Projects such as OpenStreetMap, Bycycle.org, OpenCycleMap.org, and others harness public data scraped from federal and local sites, including the Census, and churn it into maps available to and editable by the general public.

“The OpenStreetMap community has devised well-formed guidelines on how bike routes and bikeways should be marked,” says Steven Vance, a writer at Streetsblog Chicago and frequent contributor to Chicago’s bike lanes on the Open Street Map.

One problem: Those data sources aren’t that great in the first place. “Even when you do have network data, it might be utter crap — you’d be surprised by how poor and outdated some city data sets are,” says Kidd. “Part of the problem is that it’s just expensive to do it. The amount of work needed to spot check everything in your network is very awkward and time intensive.”

But as Kidd points out, a map isn’t everything. Last summer, the New York Times published an extra layer of systems information: A “bike knowledge” map for 16 major North American metropolitan areas, giving tips on everything from particularly smooth routes and quick detours to grumpy drivers and low-hanging tree branches.

But do you get your bike directions from Open Street Map, or Bycycle.org, or any other open source project? Do you use the Times’ bike knowledge, or the MapQuest open source mapping API?

You probably don’t. You probably use Google.

While open source mapping projects have the crowd at heart, Google has harnessed the knowledge of that crowd more swiftly, directly, and efficiently than any other platform or organization. The company’s Map Maker program often runs meet-ups in conjunction with local bicycling groups aimed at teaching passionate bike-riders how to package their know-how and hand it off to Google. This is one way the company has been able to create such useful maps in such a short time period.

“Oftentimes, it’s the individuals in a community who know most about what changes are happening, and about the nuances of individual roads, trails, and more — and we wanted to empower people everywhere to take mapping into their own hands so that the most important parts of their neighborhood end up on the map,” a Google spokesperson told me. “While we don’t typically share specific numbers, I can say that the cycling community is one of the most active contributors to Google Map Maker.”

By way of sheer size and ubiquity, Google already controls much of our data by way of our emails and searches, but with Map Maker, the company is explicitly courting you for that data, and then turning it into a proprietary product.

Open source maps might not be as advanced or user-friendly as Google’s, and they definitely don’t come with corporate swag, but the incentives are essentially baked in.

“Users who contribute their knowledge to Google Maps should understand that their contributions are not usable by anyone who isn’t paying Google,” says Vance. “OSM data is free to extract and use as one sees fit” — Vance uses it himself for his own Chicago Bike Guide app.

But those incentives may just not be enough to shift the crowd from hitching their bikes to Google’s convenient bandwagon.” There needs to be another technological leap in the way we do mapping, and it won’t be until that happens that we can make an open source system” to rival private, moneyed systems like Google’s, says Kidd.

It’s hard to convince the public that the funds needed for bike infrastructure data and design are really a good allocation of resources. Until then, few see any downsides to giving Google what they’ve got.

Maps are a means to an end, but also an end in themselves: A document, a proof of existence, of direction. Just like the crowd has forced cities to shift the physical infrastructure of streets, the crowd is also reshaping the means of maneuvering on those streets.

If bike infrastructure mapping is broken, then it’s just like the roads themselves. But if the means of navigating public roads is to be privately owned, how will the public push those shifts in the future?