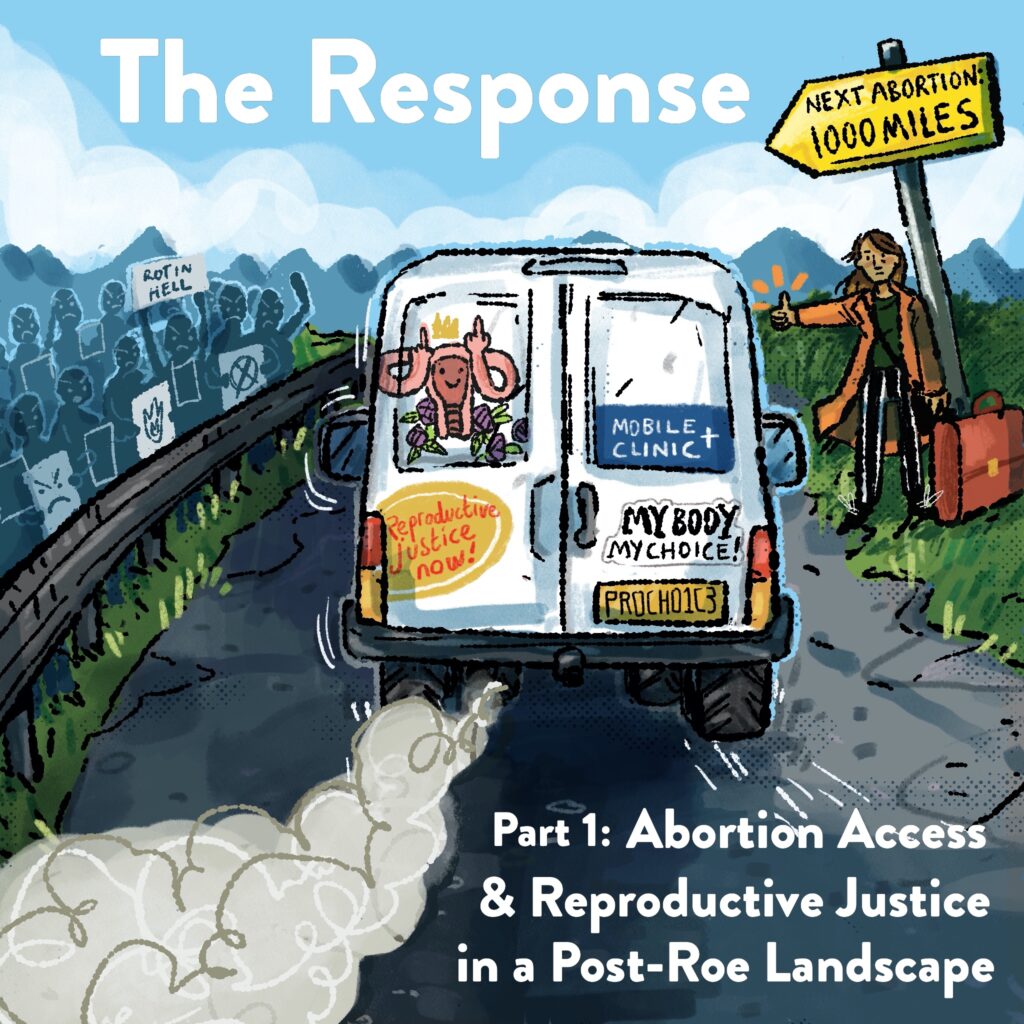

In the first of this 2-part series of The Response, “Abortion Access and Reproductive Justice in a Post-Roe Landscape,” we take a deep dive into how communities are responding to the growing abortion access crisis in the United States, sharing the stories of those impacted and highlighting a number of radical grassroots, mutual aid, and solidaristic efforts aimed at helping people access abortion in the places where it’s currently outlawed or restricted.

Abortion access has always been limited here in the United States, but since Roe v. Wade was overturned in June of this year and the Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization decision held that the Constitution does not confer a right to abortion — things have gotten dramatically worse — especially in parts of the southern United States, the Great Plains, and parts of the midwest.

In the face of trigger laws banning and criminalizing abortion in many states — as well as state-sanctioned harassment and targeted campaigns against people seeking abortions — the centuries-old movement for reproductive rights and justice has only grown and strengthened.

This is Part 1 of a 2-part series. You can listen to Part 2 here.

Episode credits:

- Series producer and writer: Robert Raymond

- Host and executive producer: Tom Llewellyn

- Additional music: Chris Zabriskie, Do Make Say Think, and Pele

- Original artwork was created by Bethan Mure

This series features:

- Julie Amaon: Family medicine physician and the medical director for Just the Pill

- Jenice Fountain: Executive Director of Yellowhammer Fund

- Gulf South Plan B: Mutual Aid organization that distributes free emergency contraception in Louisiana, Texas, Arkansas and Mississippi

- Angel Jones: Recipient of medical abortion pills

- Laurie Roberts: Executive Director of Mississippi Reproductive Freedom Fund

Listen and subscribe with the app of your choice:

For a full list of episodes and resources to strengthen and organize your community, visit www.theresponsepodcast.org.

Below is a transcript of “Abortion Access and Reproductive Justice in a Post-Roe Landscape,” modified for your reading pleasure.

[Sound collage of news clips layering on top of each other and building with radio static getting louder in the background until it hits a peak and then stops suddenly]

Laurie Roberts: Yeah, so, hi. I’m Laurie Bertram Roberts, and I am a reproductive justice activist in Jackson, Mississippi. And I was born in Duluth, Minnesota. I was raised in a very religious household. And when I say very religious, I really mean cult — I was raised in an independent fundamentalist Baptist.

My mom’s white, my dad’s Black. You know, I’m a biracial Black person. I I.D. as Black. My mom and I have always been poor. My mom, a single mom, you know, I grew up on welfare. Like I like to add the context that like literally my whole childhood, everything good I remember about my childhood was publicly funded. Like, I don’t know how to explain it any other way, but like, I loved going to the library every week — publicly funded. All the parks I went to — publicly funded. The city bus — publicly funded, right?

So like my view of the world as far as like what taxes can do and why taxes are amazing and why, you know, like mutual aid is amazing and all those kinds of things is kind of through the lens of my childhood and the things that my mom, despite being roped into this religious nonsense by my grandparents, would always be at like the local co-op, volunteering her time to make sure she could get fresh fruit for me, right? And like she always volunteered at the Y [YMCA], like she always, always doing all this like cooperative stuff on the side that my grandparents didn’t really know about. So it was always like she was doing like all this extra, like, food box stuff and like, you know, stuff on the reservation with her Indigenous friends and all kinds of stuff and barter stuff and all this stuff.

But yeah, so there was all of that. And then, you know, like life happened to me, right? I was no longer a good Christian girl. I got pregnant at 16. And, you know, like many fallen Christians, I did what my indoctrination told me to do. I got married at 16. And at 17 I almost died in a Catholic hospital that wouldn’t give me an abortion when I was having a miscarriage, because there was a heartbeat, a heartbeat, quote unquote, in my embryo. And so they sent me home and I almost hemorrhaged to death. And so that kind of started my unraveling of my beliefs that I had been taught. And then just life kept happening. You know, I needed an abortion. I couldn’t afford one.

And I was a turn-away patient. I needed an abortion another time. And Planned Parenthood gave me fantastic, fantastic care. And actually, I ended up not getting an abortion because I had a miscarriage. But like the care they gave me in telling me that I was going to have a miscarriage was amazing. They gave me back my money. They, like, made sure I got follow-up care with my Medicaid provider. And the funniest thing about that is that I was raised being told that Planned Parenthood would give you an abortion even if you weren’t pregnant. I just want you to think on that for a second that Planned Parenthood was so greedy that if you went in there and you weren’t even pregnant, they would give you an abortion. So imagine me laying there and they give me this ultrasound and they say, you’re already starting the process of having a miscarriage. Here’s your $450 back. Have a nice day and go follow up with your Medicaid provider. So it was just like that kind of lifted the rest of the veil for me.

And then I just had a lot of other stuff. Like, I was denied an IUD when I wanted one. I couldn’t get my tubes tied because I — there were only Catholic providers where I lived. I just had a lot of reproductive injustice. Right? And I just think that for a lot of us, especially as Black women or Black femmes, we just take that as normal, like the policing of our bodies, the policing of our lives.

[Music: Pele – Nude Beach. Pin Hole Camera]

Tom Llewellyn: Laurie’s experience isn’t just an isolated story, unique to a handful of individuals — it’s a story that could be told in a million different ways by a million different people: a story about reproductive justice — or, more accurately, a lack thereof.

Abortion access has always been limited here in the United States, but since Roe v. Wade was overturned in June of this year and the Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization decision held that the Constitution does not confer a right to abortion — things have gotten dramatically worse. Especially in parts of the U.S. like the deep south, where Laurie lives.

In the face of trigger laws banning and criminalizing abortion in many states — as well as state-sanctioned harassment and targeted campaigns against people seeking abortions — the centuries-old movement for reproductive rights and justice has only grown and strengthened.

The movement takes many forms, but in this 2-part documentary episode of The Response podcast, we’re going to explore the people and organizations working on the frontlines of the abortion access crisis — those grassroots, mutual aid, solidaristic efforts to help people in the places where abortion has been outlawed and criminalized get access to the reproductive services they need.

We’ll start in the deep south…

[Music concludes]

Laurie Roberts: Who are we? We are a ragtag group of dedicated volunteers, hopefully, to get sustainably paid this year. All of us. But we are a reproductive justice organization that funds abortions and does practical support for abortion — always have.

Tom Llewellyn: The Mississippi Reproductive Freedom Fund, which Laurie founded in 2013, offers financial assistance and practical support to people seeking abortions as well as free emergency contraception and community-based comprehensive sex education.

Laurie Roberts: We give away condoms and lube and dental dams, and we do instructions on natural family planning and cycle beads, and we give away [inaudible]. I mean, like basically if it’s a legal contraceptive-like barrier method that we can distribute, we got you. Like we got you and we can teach you about it. We train peer-to-peer sex educators. We do sex ed in the community. We have a free pantry and a little free library on our main property, the Fund Shack. We have a lending library. We have a bunch of other stuff that we can lend out to people. Everything from like cake pans for birthday parties to mixers to like cotton candy machines for other like community groups. So you don’t have to pay to rent those kinds of things for things. So like we’ve got a cotton candy machine and a popcorn machine and a slushie machine that people can borrow.

I know this is like a long list of stuff, but we like — we have all we do all kinds of stuff. We have a diaper closet and a period supply closet, including stuff for people who have incontinence issues and adult diapers. We deliver groceries to folks. We have helped with the ICE raids that happened. We’ve helped bail people out, especially people who have been criminalized for the pregnancy outcomes. I think that’s mostly it. I think I covered most of it. Maybe, I don’t know. I mean, we help people with temporary housing. We help people pay their property taxes so they don’t lose their house, all kinds of stuff.

Tom Llewellyn: Mississippi has the highest poverty rate of any state in the US — nearly 20 percent of Mississippians live in poverty. In fact, the deep south as a whole is the most impoverished region of the US, with the surrounding states of Louisiana, Alabama, and Tennessee all ranking in the top ten. States in this region have also passed some of the most criminalizing abortion legislation since Dobbs — but it’s not like they were reproductive justice beacons before, either.

Jenice Fountain: Things already have been an issue before the Dobbs decision, because before Dobbs, there were still people that could not access abortion. It was not an affordable thing. It was not something that people could tangibly do in Alabama. We’re in Birmingham, very populated. There’s not a clinic here in Birmingham that performs abortions.

Tom Llewellyn: Jenice Fountain is the Executive Director of Yellowhammer Fund based in Birmingham, Alabama.

Jenice Fountain: Okay, so Yellowhammer Fund is a reproductive justice organization. Pre-Roe v Wade following we were doing a lot of abortion funding, maybe about 350 clients a month as far as funding. We’re also funding their practical support around abortion as well, like travel, childcare and doing a lot of the preventative measures as well emergency contraceptives, condoms, safe sex kits. And we were doing this based out of Birmingham now, but we were serving like Mississippi, Alabama, the Florida Panhandle, and a lot of the Deep South places that folks don’t usually get reached at.

Tom Llewellyn: Before the Dobbs decision, the main barrier to abortion access throughout many parts of the country — but particularly in regions like the deep south — were what’s known as TRAP laws — or Targeted Restrictions on Abortion Providers. These laws imposed costly, severe, and medically unnecessary requirements on abortion providers and women’s health centers — things like location requirements, unreasonable reporting demands, or even 24 or 48-hour wait periods to receive care. These laws were pushed by anti-abortion politicians under the guise of “women’s health,” but their real aim was to make it more difficult for people to access abortions.

Jenice Fountain: In Alabama they got to make sure you’re okay to make your own decisions and wait 24 hours after a counseling appointment to come back. And that’s not feasible for a lot of families, especially low income to drive an hour, come back, do it again, get childcare both days, pay for gas both days for a procedure that’s already very unaffordable. Or even just if you’re disabled. Like, how do you get to those appointments multiple times? If you’re undocumented, how do you get an appointment at all? Like it was very inaccessible. So when people were relying on legality, it was very disappointing because a lot of folks that we’re serving is not a feasible thing. They could have abortion. It wasn’t something they could even fathom doing under the circumstances they’re already in. If they’re already choosing between food and gas, you know, it’s like, how do you get $600 for a procedure?

And now, of course, it’s even worse in that the people that would have accessed abortion, at least, can’t. And when you look at the numbers and looking at Alabama and how many people are dying in childbirth in Alabama and especially Black women being three times that amount of white women you like — it doesn’t align, like there’s no amount of work being done so that people don’t die in childbirth. There’s not enough work being done to get Alabama out of the top five most food-insecure states. We are like the second poorest state, second to only Mississippi. What should people do?

Laurie Roberts: Yeah, so I always called it an abortion desert.

Tom Llewellyn: Here’s Laurie Roberts again.

Laurie Roberts: With like a few oasis points. So, like, Atlanta was like an abortion oasis, right? Tuscaloosa was like a little abortion oasis. Jackson, you know, Baton Rouge, New Orleans, they’re all gone now. All of them. There’s nothing. It’s obliterated.

Tom Llewellyn: According to Bloomberg, it’s been estimated that a quarter of the country’s abortion clinics have closed since Roe was overturned. Statistics show that there are roughly 33 million women of child-bearing age living in states with existing or expected abortion bans — and now, some will have to travel hundreds or even thousands of miles to access an abortion.

But traveling was already a huge barrier even before Roe was overturned. This is why the Mississippi Reproductive Freedom Fund — along with many other groups — have been helping people access abortions by not only providing funds to assist with transportation, but in some cases even providing the transportation itself.

They’ve mostly used their own cars or rentals, but a few years ago The Mississippi Reproductive Freedom Fund acquired what Laurie calls the “abobo bus,” a 12-seat van that’s large enough for people to lie down in. It’s worked pretty well for them, but, since they got it for cheap, the “abobo bus” does tend to break down. It was actually out of commission when we spoke with Laurie.

Laurie Roberts: Sad face. Let’s hope it can be fixed. I don’t even know. But so generally someone will call and we’ll troubleshoot all the ways to get them to an appointment. Because giving them a ride is not the first one that we go with. Giving someone a ride is basically kind of like the last option that we go with because it’s logistically the hardest thing for us to do. So we will generally troubleshoot with — do they have someone who can take them? Is there like, is there a way for us to fly them the place that they need to go, depending on how far it is? Like, what are the alternative ways for us to get them there?

And then like if — or if they just call and say that the issue is they need a ride or they’re referred to us for a ride, then we immediately start figuring out who can drive them. We usually send drivers in two people prepares for a couple of reasons. One, fatigue, but also just safety and, you know, obvious reasons, right? And also, we usually have one person that’s a support person at all times for the person who’s getting their abortion because we have abortion doulas. So yeah, so that gets put in motion.

And then the abortion doula is usually that person’s contact person. From that time on, we get them their appointment, figure out when we’re going to take them for their first appointment, get them a schedule on when we’re going to pick them up, where they’re going to, where they’re going to pick them up if we need to pick them up away from their house. Do we need a code name? Do we need — I mean, like some of this stuff sounds like some real like James Bond stealthy stuff. But honestly, for people who are in DV relationships, sometimes we cannot pick them up near their house. Or if we do, we need to pick them up in a — we can’t pick them up in our accessible vehicle. We need to pick them up in a car or we need to — it can’t be like our male driver that drives a lot of times we have to send like our little suburban white lady who looks like somebody, you know, Girl Scout cookie mom, like, you know what I mean? Like, we have certain people that we send for certain stuff, so that’s a whole thing. I know I’m giving you a really long answer, but there’s a reason.

So there’s all of those things to troubleshoot. And then we send the team out, they pick them up, we drive them there. Usually, if it’s only a 24-hour waiting period, the appointments are booked back to back. So then you’ve already booked the lodging for the support people in the person that’s going. And then everybody’s got their budget for spending their food and all of that. And then that’s pretty much it. The support person goes with them for their appointment. There’s usually someone up with a person — it used to be if we had someone who was going out of state. And even now, usually if we’re driving with someone out of state, they’re a little bit later along because a lot of times our earlier people don’t need a lot a lot of support like that.

So a lot of times we’re staying up with them to make sure they take their meds on time or they’re not nauseous or that they’re okay. And then we make sure that they’re good to go when they’re all done with their — however long the procedure time is. If it’s a day just the next day, or if it’s a two-day procedure and then back on the road again, make sure they get home, follow up with them for the next couple of days, follow up with them in another couple of weeks, and then that’s it.

[Music: Pele – Hospital Sports]

Dr. Julie Amaon: The mobile clinic idea was our executive director’s back in 2020 when we started — but we were thankfully able to mail really early during the pandemic and so pivoted pretty quickly. But since, let’s see, September of 2021, when Texas passed their SB 8 restrictions, that’s when the mobile clinics kind of came back to fruition.

Tom Llewellyn: Dr. Julie Amaon is a family medicine physician and the medical director for Just the Pill — a nonprofit providing telemedicine and both in-person and by-mail medication abortion and contraception. They operate mostly in Colorado, Minnesota, Montana, and Wyoming.

Dr. Julie Amaon: We were trying to figure out, Just the Pill, how we could serve Texans and other people traveling from more restricted and banned states. So the idea was we had two mobile clinics built out. One has medication lockers in the back for pickup, and the other one is just kind of a mobile exam room, essentially.

And so that was started, let’s see, a couple of months ago, we’ve seen about 60 patients for medication abortion pick up. And the reason we’re able to do that in Colorado specifically is because they don’t have a 24-hour waiting period like we did in Minnesota to start with. So patients can travel from what other state they’re coming from, have their telehealth, visit with the clinician, and then be able to meet the mobile clinic and pick up their medications. And then hopefully the same for our procedural units. They’ll be able to have all of their — as much of their visit done via telehealth to save time and resources for patients and then come to the clinic and have their procedure and be able to go.

Tom Llewellyn: For now, Just the Pill’s mobile units are only delivering medication abortion, but they’re planning to provide procedural abortions by the end of this year. However, there’s still a lot of work that needs to be done in order for that part of the program to run smoothly and safely.

Dr. Julie Amaon: Just over the last five to ten years, it feels like the violence towards abortion providers and clinics is just kind of escalated. And I feel like after the Dobbs decision, it’s just been kind of the same for that. So when we were looking at having the mobile clinics built, we knew that we would be very concerned about where they were parked and had to have partners on the ground that would be comfortable with us there and that we feel safe.

Making the mobile clinics bulletproof was something that we just thought was necessary in a climate that we’re in. It’s unfortunate that we have to think about that, but that is the world that we live in. So we want to make sure that our staff and patients are safe. And so along with the bulletproofing and making sure that we have strong community partners, where we’re parking is something — that’s kind of why we’re pushing back our procedural clinic is trying to find the right place, or the right places to be able to serve our patients — where everybody’s safe.

[Music: Do Make Say Think – The Landlord is Dead]

Tom Llewellyn: In May, the National Abortion Federation released its 2021 statistics on violence and disruption against abortion providers. The statistics showed a significant increase in stalking, blockades, hoax devices or suspicious packages, invasions, and assault and battery.

[News clips]

Since 1977, there have been 11 murders, 42 bombings, 196 arsons, 491 assaults, and thousands of incidents of criminal activities directed at patients, providers, and volunteers.

[News clips]

According to a piece by Vera Bergengruen in Time Magazine, armed demonstrators and extremist groups like the Proud Boys began gathering much more frequently at abortion-related protests following the Supreme Court’s overturning of Roe. This includes gatherings at 27 abortion-related events in just the first week following the overturn — a 160% spike over last year.

[News clips]

[Music concludes]

Tom Llewellyn: Since the Dobbs decision, Just the Pill has seen an 83% increase in patient requests for appointments and has doubled their staff to meet this rise in patient demand. They’re still working to onboard new staff and clinicians as quickly as possible — but trying to do so sustainably.

Dr. Julie Amaon: We’re in the marathon now, we are not in the sprint anymore. Right. This is going to be the lay of the land for a long time. We didn’t get here overnight and we have a long way to go to make it better than it was before. Roe v Wade was just a skeleton to start with. We need to build it back and make it better than before. So we have a long road ahead of us. So we’re just trying to keep our head on straight, try to see as many patients as possible and making our organization something that what we’re doing in Colorado, how can we replicate that in other states and expand? So that’s where we are right now. But I’d rather be doing this than anything else. We’re making some headway.

Jenice Fountain: In terms of the future, as much as I’m disappointed to know what the trajectory of some folks lives look like because they’re going to fall through the cracks of, like, all of the support that’s hard to get to a lot.

Tom Llewellyn: Here’s Jenice Fountain again.

Jenice Fountain: As much as I feel saddened by that I’m still hopeful because there’s organizations that are dedicated to doing the work and there’s a lot of people that are dedicated to this movement. And as much as like laws do seem to govern everyone, I really feel like posted their power for movements. So I’m really just interested in seeing what we can like what type of base building we can do to fight back. Because I don’t think it’s something that we can just lay down and say, okay, well, we don’t have autonomy over our bodies. It’s fine. It’s not fine. I don’t think anything in history was just gained from this bailing out and Yellowhammer Fund doesn’t intend to bail out at all.

[Music: Pele – A Scuttled Bender in A Watery Closet]

If you enjoyed “Abortion Access and Reproductive Justice in a Post-Roe Landscape,” please check out all of our other episodes of The Response and get your copy of our free ebook.

|

Download our free ebook: “The Response: Building Collective Resilience in the Wake of Disasters” |