One of the most powerful things about solidarity economy initiatives are their intensely local focus. Based out of communities of workers, neighborhood organizations or social groups, the solidarity economy flourishes on organizing local projects and making them sustainable. But sometimes intensely localized organizations can run into problems: how do they reach out to find new customers, volunteers and funders? And how can they create the sort of power that truly demonstrates viable alternatives to the major economic processes they’re up against?

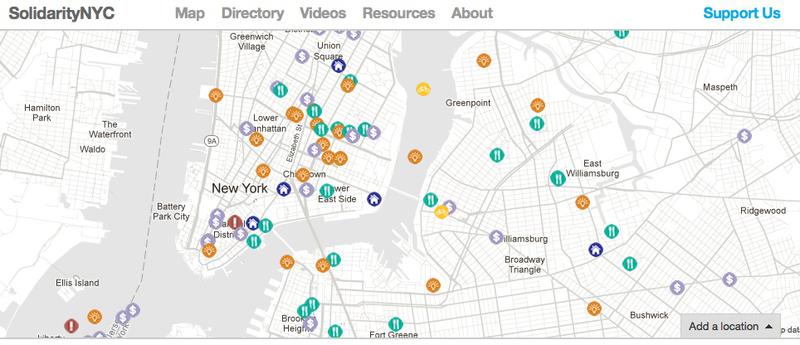

SolidarityNYC, a group I’ve profiled here before, and which has mapped New York City’s solidarity economy, has a new report called “Growing a Resilient City.” The report grew out of conversations with the dozens of solidarity economy businesses about what they need moving forward. The report does not just speak to the needs of New York, however. It is a valuable overview of the techniques, plans and needs of anyone looking to build solidarity initiatives anywhere in the country. And, in true solidarity economy fashion, it was written through the participation and collaboration of all the people that it discusses. (PDF of the report)

The report is broken into five sections, and a brief overview of the sections will give an idea of the most powerful ideas in the report.

Section I: “Growing Visibility”

One of the major struggles facing solidarity economy businesses is reaching new people outside of the community. Some of the solutions to this problem proposed within this report include a solidarity economy infoshop, which would be able to point new customers and volunteers to whatever they needed, joint marketing and web presences, collaboratively produced media products between multiple businesses, and education and community teaching programs.

Section II: “Strengthening Our Organizations”

It’s never easy to run a business built on solidarity and community, rather than profit. Many businesses faced funding shortfalls, low or no wages, administrative and legal problems, etc. In short, they need money, people and technical resources. This section is particularly valuable, as it lists dozens of possible solutions to these problems, including a jointly managed loan fund, shared space and rent, a citywide volunteer database, and much more.

Section III: “Building Economic Power”

Once businesses are off the ground, how do they establish themselves as a serious force in the city? Some ways suggested by participants included pledging to only get goods and service from other solidarity economy businesses whenever you can, create an actiivist/movement orientation, fight for participatory budgeting, and facilitate buying clubs for coops.

Section IV: “Building Political Power”

Just as important as economic power, without political clout it can be hard to challenge the regulatory environment which is designed around private, profit driven enterprise. Suggestions include building a unified lobby program, integrate with activist and movement based politics, and collaborate with organizations fighting injustice.

Section V: “Structures for Collaboration”

This is perhaps where SolidarityNYC has the most possibilities for intervention. SolidarityNYC can help be an intermediary in producing these bonds of collaboration and transforming disparate groups into a solidified movement. There are many struggles embedded in this project: wariness of groups to devote resources to coordination, concern about questions of community needs being different, etc. But SolidarityNYC sees a lot of potential for new organizations that can meet the diverse needs of their community of businesses while respecting those differences.

There is a lot of work to be done for the solidarity economy, but, the upshot of the report shows that members of New York’s solidarity economy want to build a movement together and are full of excellent ideas to make that happen. There are many challenges facing such a project, in particular

“participants underscored that respect for difference must be central to these efforts. A hallmark of solidarity economy initiatives is community control, and a culture of inclusion, which embraces democratic and bottom-up design. Our differences span not only identity but also practice, and an important strength of these initiatives is a willingness to innovate and apply creative solutions to community problems.”

This report points toward the fact that the New York City solidarity economy community is ready to get stronger, and is facing the movement’s challenges head-on.