My heart lifts out of my chest when I think about and feel the work of #LandBack, land return, and reparations. Then, my chest tightens when people ask me to talk about the legal “nuts and bolts” of land return.

I’m writing this for the people – especially those who own land – who are feeling animated toward repair, healing, and return of land to Indigenous and Black people. I’m also writing it for myself. As a land justice lawyer, I have tinkered with the nuts and bolts for 15 years, and I’ve found them increasingly hard to stomach. Now, I’m attuning to the ways law and legal tools have disrupted the flow of inspiration that motivates land return.

I’m writing this for the people – especially those who own land – who are feeling animated toward repair, healing, and return of land to Indigenous and Black people. I’m also writing it for myself. As a land justice lawyer, I have tinkered with the nuts and bolts for 15 years, and I’ve found them increasingly hard to stomach. Now, I’m attuning to the ways law and legal tools have disrupted the flow of inspiration that motivates land return.

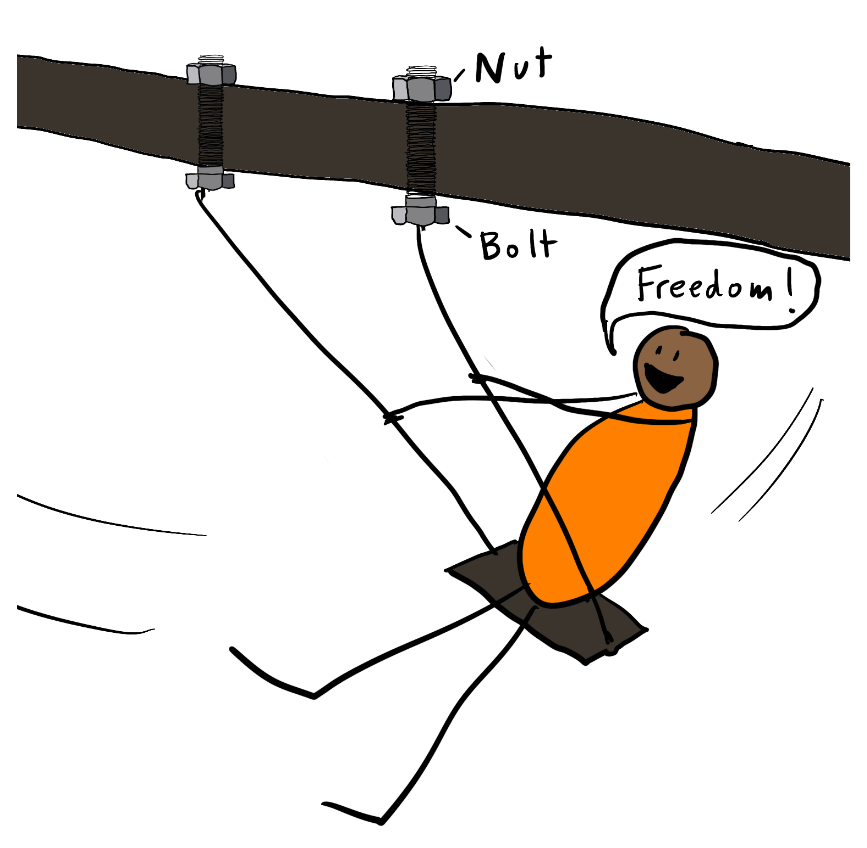

When you screw a literal nut onto a bolt, you immobilize things and fix them into place. Sounds cold, hard, and lifeless, right? But there’s a place for nuts and bolts. They bring stability, and certain forms of stability are essential to life and living systems.

I often picture the cartoon on the right to remind myself that nuts and bolts can anchor liberatory movements, IF we use them mindfully, with the intention that they support – not disrupt – the healing instincts and thriving of life. For example, there are laws, legal “tools,” and financial “instruments” that can protect land justice groups from threats of exploitative finance systems and extractive real estate markets.

I often picture the cartoon on the right to remind myself that nuts and bolts can anchor liberatory movements, IF we use them mindfully, with the intention that they support – not disrupt – the healing instincts and thriving of life. For example, there are laws, legal “tools,” and financial “instruments” that can protect land justice groups from threats of exploitative finance systems and extractive real estate markets.

But how can we strike a balance in such an imbalanced world? When it feels like a lot of things are spiraling out of control – wealth accumulation, land grabs, ecosystem destruction – it’s very tempting to want to hold everything in place with strong nuts and bolts.

15 years ago, as I was graduating from law school, I decided that my work would be to create a more sharing and cooperative world … using legal tools. When you are about to graduate from hammer school and become a hammer, everything looks like a nail. Since then, I’ve seen how legal tools can help, but far more often now, I see how they hurt, how they disrupt patterns of care and repair that occur naturally in social groups, in nature, and in life.

At Sustainable Economies Law Center, my colleagues and I are in a constant discussion and process of changing how we use legal tools. We started the Radical Real Estate Law School as a space to learn, teach, and grapple with big questions, like: What is real estate? What is radical? What are the roots of human relationships to land?

Returning land to Black and Indigenous people is such important work to us; it feels sacred. On one hand, we yearn to “streamline” land return by creating handy legal tools and easy step-by-step guides. We start to draft them, then another part of us cringes, because how could we ever distill something so sacred into, say “Land Return in 3 Easy Steps?”

All that said, below I offer my thoughts on tools that could be useful to land justice movements. Along with this, I express my deepest hope that such tools (and the professionals who tend to make them – lawyers and realtors) do not bring unnecessary complexity, overwhelm, suspicion, or anxiety that could disrupt the flow of care and repair animating land return efforts.

Deeds as delusion and violence

Let’s start with how delusional and violent our present real estate system is. The people who have benefitted from accumulating control of land have done so by forcing all of us to operate within a certain framework: one that divides land into parcels, then grants dominion over the land to certain people, with the ability to exclude others. This is the framework of private property ownership.

This is a comically silly idea, if you think about the core of it. Imagine undivided land and ecosystems, with groups of people self-organizing in widely diverse ways to live as inseparable parts of that land. Next, imagine a grid superimposed on it, attempting to replace natural, organic, and permeable boundaries with severe-looking square boundaries. Next comes a grant of dominion with ritualistic execution of paperwork called a Deed, which is a document containing official-looking lines and squares, and validated by some important-seeming person, called a Notary, with special powers to “MAKE IT SO.” I call it comical, because it would be hilarious if that’s all it was and we took this bad idea of property ownership seriously. It’s like a bad impersonation of divinity.

But where it becomes not-funny – and why we do take it seriously – is that those who created this framework and its rituals of domination also have literal weapons, fences, and barbed wire. They police these hard boundaries, and for many people, the only choices are to accept the lines or die.

So, while I can laugh at how silly it looks to superimpose boxes over a flowing landscape, and at how a deed is just a flimsy piece of paper, I also take very seriously that whoever has their name on a Deed has the violent power of police behind them, to protect their control and exclusion of others. Each deed represents the violent severing of the land, ecosystems, and living relationships. A deed may be a flimsy piece of paper, but it is also one of the heaviest things we must hold as we begin this work. In the U.S., most land rights begin with a deed, and that’s our inevitable starting point. Where to go from here?

Here are three questions to explore:

- How can we ease the violence of a deed and soften its hard boundaries?

- How and when should we shepherd the deed into the hands of people who will steward it?

- What legal tools can support long-term healing and repair?

On the first question: How can we ease the violence of a deed and soften its hard boundaries?

There are social, cultural, interpersonal, and spiritual ways to ease the violence of the deed, and those show up in the infinitely diverse ways that we live together and weave webs of relationships around the land. We see examples everywhere: One person owns the land, but dozens of community members garden and enjoy time in it.

But this web can be broken apart in an instant, because of that legally-supreme Deed and all the police power behind it. The owner can sell it, declare trespass, etc. This is why it is so important to develop legal tools to protect these soft and vulnerable relationships from the start. So we may have no choice but to protect these soft and vulnerable relationships using hard legal tools, nuts, and bolts.

The legal system offers us several common tools. In fact, these tools have deep roots in our legal system, because they exist to mitigate the original bad idea of “ownership.” As soon as we superimpose hard boundaries on the land, we realize that nothing in our human and beyond-human natures wants to adhere to those lines. Water flows through, people travel through, and animals wander. Humans try to control and create some order to all of this flow, but we can’t deny it entirely.

So we use tools like licenses, easements, and leases to ease the hard boundaries of ownership in the present. These three things all basically do the same thing: With each, the owner says: I retain the some of the powers and responsibilities granted to me by the law, and give others to you, whether it’s to live here, visit, pass through, tend the land, enjoy or use what is here, etc. Another tool to do this in the present is co-ownership – putting multiple parties on a deed (as tenants in common), and then detailing your understanding with each other in a co-ownership agreement. Amazingly, in Life, land can be shared without the ritual of legal documents. But under The Law, those informal agreements are not respected, and therefore not protected without the paperwork. The document, itself, is essential to protect the relationship.

So we use tools like licenses, easements, and leases to ease the hard boundaries of ownership in the present. These three things all basically do the same thing: With each, the owner says: I retain the some of the powers and responsibilities granted to me by the law, and give others to you, whether it’s to live here, visit, pass through, tend the land, enjoy or use what is here, etc. Another tool to do this in the present is co-ownership – putting multiple parties on a deed (as tenants in common), and then detailing your understanding with each other in a co-ownership agreement. Amazingly, in Life, land can be shared without the ritual of legal documents. But under The Law, those informal agreements are not respected, and therefore not protected without the paperwork. The document, itself, is essential to protect the relationship.

But the content of the document creates a wide open space in which we can be far more thoughtful about our relationships, and mindful to not extinguish the spark of care and repair that brought people together in the first place. If you’d like to see an example of an easement where we are trying to be imaginative in weaving webs of nurturing relationships with the land, see this Kinship Conservation Easement.

Let’s take a short detour to talk about documents, what we want them to mean, and what nuts and bolts we do or don’t want in them.

Sadly, tools like leases and easements can perpetuate the violence of separation and policing, particularly when there are strong power imbalances between parties. Leases and easements can be 20 to 80-page documents with ghastly legalese that I promise you that many lawyers are only pretending to understand. Think of the toxic circumstances such documents create at the outset of an important land-based relationship: People are afraid of what they don’t understand, feel extremely challenged to even read it, and when they see words like “default,” “damages,” and “enforcement,” it sets a tone of distrust and anxiety. The professionals, lawyers especially, behave as if all of this is gravely important because without such things, our profession would not even be necessary, and $500/hour fees would be recognized as theft.

To untangle ourselves from the distorted thought patterns of our legal profession, my Law Center coworkers and I enjoy taking 40 page documents and condensing them into 12 sentences, making space for the parties to breathe their own life into a document.

In the process, we discover that much of what makes legal documents long and insufferable are harmful nuts and bolts. The documents attempt to predict and exert control over every contingency, over every scenario we can imagine unfolding through time, and to create a clear and inviolable rule, like: if you don’t pay rent, I can evict you using the power of the courts and the police. This type of nut and bolt holds the power and material comfort of one party firmly in place, while validating control over and violence toward another.

The party on the deed tends to have the upper hand in the relationship. So if you are in this position of power, my advice is to avoid using document templates or trying to replicate pre-existing formulas, if you can. The same inspiration and wisdom that guides you toward land return can also guide you to craft kind and nurturing relationships. Try to distill your intention to a sentence, like: “We want to live on this part of the land, while giving Land Trust the rest; and when we die, Land Trust will have all of the land.”

After stating a clear intention, you can collaboratively explore details, like: Who lives where, what the migrating butterflies need, how you will come together to navigate change, and so on. There will still be nuts and bolts to hold some things in place, for example: No one will ever cut down the trees that fill each year with migrating butterflies. But then you might soften the bolts, like: “Except if the tree is threatening to fall on a house.” Other bolts might include: “We agree no one will use the land to secure a loan, because then we’d risk losing the land to the speculative market.” And in considering the web of relationships that you are tending together, you might still end up with a long document, with some things bolted into place, and other things that more gently clarify your shared intentions and values. It should balance openness – to leave you space to be creative, to adapt together with care over time – with stability, and with some things in place so you can breathe easier knowing that, say, butterflies can return long after you are gone.

Because relationships relatively free of oppression are so important, particularly when land is shared and lives intertwined, we should be careful anytime we use bolts – i.e. legally enforceable obligations – to control one another.

I believe one of the most important legally enforceable obligations to put in a document is – somewhat ironically – an agreement to not rely heavily on legal enforcement, to avoid inserting the logic of domination and the power of policing into the relationship. You can instead make clear agreements to come together periodically or as needed, always referencing your shared values and intentions, to navigate change and solve problems together, before ever resorting to courts. You can specify some minimal details about the shape, duration, and frequency of such comings-together, whether there will be intentional mediation and facilitation, what practices you’ll engage in to show up in good faith and non-defensively, and so on.

I believe one of the most important legally enforceable obligations to put in a document is – somewhat ironically – an agreement to not rely heavily on legal enforcement, to avoid inserting the logic of domination and the power of policing into the relationship. You can instead make clear agreements to come together periodically or as needed, always referencing your shared values and intentions, to navigate change and solve problems together, before ever resorting to courts. You can specify some minimal details about the shape, duration, and frequency of such comings-together, whether there will be intentional mediation and facilitation, what practices you’ll engage in to show up in good faith and non-defensively, and so on.

The Law Center has seen and supported a growing number of clients to draft leases that have no legally-enforceable obligation to pay rent. What they have instead, are legally-enforceable obligations to come together and problem-solve financial stresses and other tensions. Here is a slideshow we created, inspired by octopuses, to encourage people to take a more open and trusting approach to agreements.

This transitions us to the second question: How to shepherd deeds into the hands of the hands of caring stewards?

Given the weight that deeds carry in our legal system, there is a sense of safety people get when they have their name on a deed. But we can ask ourselves: Why does it feel safer to OWN land? The answer burns: It’s because our legal system uses police power to protect people whose name is on the deed.

It’s for that reason, I would especially urge white landowners to explore transferring title, even if you want to remain on the land. Rather than lease, license, or give an easement to a group, flip the arrangement: Grant them the deed, and retain the relationship you need with the land by holding the lease, license, or easement yourself. You can transfer the deed, and retain a life lease. Or you can keep the deed, offer a lease, and arrange for transfer on your death.

Legally, the direction of the relationship may not matter – the lease is legally enforceable, too. But spiritually, it does matter. How does it affect your spirit? How might it feel to a group from whom land and lives have been violently taken? Even if we abhor the system of land ownership and the violent role of deeds, it feels different and safer for the person who is on the deed.

When to transfer it?

I’d advocate that many people transfer title now, rather than in the future. The future, whenever that is, is an increasingly uncertain, fragile, and frightening place. Transferring title now can remove a lot of uncertainty and fear that could prevent strong land relationships from forming.

That said, transferring land ownership now is not always going to be ideal. In some states, the transfer will trigger a spike in property taxes to be paid by the new owner. In some situations, like with land under a mortgage, the lender will not allow it. In other cases, people may not be ready to receive the land.

In this case, you can still set land on a path to being transferred in the future, and you can generally bolt that in with legal documents, such as purchase options, rights of first refusal, a life estate, and irrevocable trust. With a purchase option, you could say: I grant ____[name of tribe, cooperative, or nonprofit] the option to purchase the land for $50,000 any time before 2030, and the organization may assign this option to any organization it determines to be advancing racial justice.

When you use tools like those to lock into place the future transfer of the land, it is far more powerful than simply using conventional estate planning documents like wills or living trusts, both of which are revocable instruments. The only point at which those estate planning tools securely bolt in is when we die (or otherwise become incapable of handling our financial affairs), which is almost always something we hope will happen a long time from now. In essence, most estate planning tools are flimsy because they are revocable, generally many years away in giving benefits, and leave a lot of uncertainty for those receiving land.

It might sound scary to bolt down a future transfer when the future is uncertain. But that’s also a reason to do it. Returning to the question of balance: I’ve encouraged openness, flexibility, and adaptability, balanced in with the occasional bolt to hold things in place. What we can do now is make commitments that flow with the healing inspiration that is currently moving us – the inspiration so powerful it is moving us to tears – and protect that flow from the potential that our own minds (or the minds of any heirs, people holding power of attorney, or trustees of our estate) can later be hijacked by fear and scarcity-driven logic and need for control and domination.

On the third and final question: What legal tools can support long-term healing and repair?

The negative counterpart to this question might be: How do we prevent the logic of control, domination, and extraction from recapturing this land and those in relationship to it? The framework of private property ownership is so deeply embedded in our culture, it is bound to insert itself again and again in our relationships and organizations. It can feel like a paradox: We’re trying to escape the logic and tools of control, but we need some control to do that. Again, we return to the question of balance. I struggle a lot with this particular issue, and the tools I suggest tend to rely on context and the potential threats.

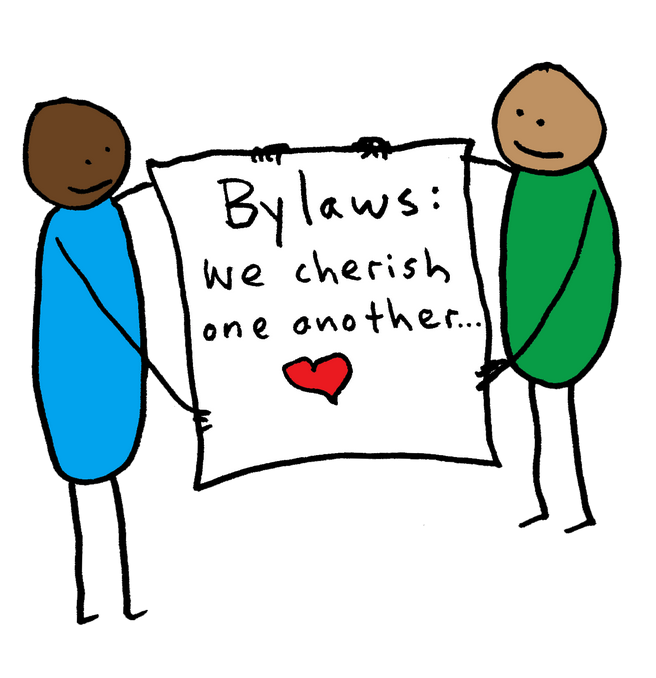

Generally, I’d suggest a minimalist approach. A minimal level of solid protections can make a world of difference in shifting mindsets away from profit and toward stewardship. We can bolt just a few things into place, like: No one can ever sell this land for more than $50,000. And: No one who lives here can ever be required to pay more than $____. And: This land may only be sold or given to a nonprofit or tribe, never to a private for-profit. Depending on the organization you transfer land to, these protections may already be built into the recipient’s organizational structure. That’s true of many land trusts, and it’s true of, for example, the East Bay Permanent Real Estate Cooperative. Once they take title to land, the Bylaws (written in cartoon) strongly protect it from returning to the speculative market.

Without sharing details that would implicate any of our clients, their funders, or certain local governments, I can share that many BIPOC-led land projects are under threat of becoming burdened and immobilized by commitments other parties demand of them, like recording covenants guaranteeing land will forever be used in a certain way, such as for housing, health care, the arts, etc. These sound like good things that the world needs, but on balance, do we really want to curtail the autonomy and freedom of groups in this way?

In sum, when just a few key protections are in place – either because we put them into a land agreement or because the land stewardship organization has already put them there – then we can leave a lot of things open, let go of the impulse toward control, letting the community and future generations determine the rest.

There is so much more to say, but for now, I’ll leave you with some resources to help you deepen your understanding of these topics:

- Legal Structures for Radical Real Estate video and slides

- Land Justice Futures workshop videos, hosted by Nuns & Nones, including Session #5 on “Nuts & Bolts”

- How to Rematriate the Land: Practical Considerations for Practitioners, Property Owners, and Supporters

- Handout: Nonprofit or Cooperative for Radical Real Estate Projects?

- Permanently protecting community assets from sale (short cartoon workshop)

- Legal structures for social transformation (short article)

- How octopuses can inspire legal documents

- Cartoon Bylaws of East Bay Permanent Real Estate Cooperative

- Article on Housing Justice Easements

- Example Housing Justice Easement

- Experimental document: Kinship Conservation Easement

- Three Legal Principles for Rebuilding the Commons (article)

- Legal Structures for Economic Transformation (1 hour cartoony workshop)

- Law and Land Craft short workshop on cooperative real estate for artists

- Radical Homeownership (Part 1 webinar)

- Legal Tools for Radical Homeownership (Part 2 webinar)

- The Pathologies of Homeownership (short cartoon)

- The History of Land Grabs and How to Fight Back (webinar)

- UnSelling MamaEarth: Povertyskolaz Teach How To Build A Homeless People’s Solution to Homelessness (webinar)

- Liberating Land Use: How Zoning Promotes Cultural Genocide and White Supremacy & How We Fight Back (webinar)

- Resource library: www.CommunityHousingLaw.org

- Fair & Just Commercial Lease Toolkit

- Cohousing Toolkit

- Now is the time to take radical steps toward housing equity YES! Magazine article

- Guidebook: Mutual Aid Legal Toolkit

- Mutual Aid and the Law (video)

- Legal Frontiers of Foundation Investments (cartoon)

- The Forbidden Eroticism of Real Estate

- Private Property is a Fictitious Notion

- #RadicalRealEstateWeek Recap

- Social housing is the only way forward

- Teachgiving

- A Life (un)Determined by Borders: Healing with the land and with Each Other

- Organize, Reach Out, Assemble, GROW!

This is a slightly edited version of a living document. You can access the original here.