Truth is more urgent than fiction.

It's a feeling that anyone reading environmental reports (like, say, “Planetary Boundaries,” or even “NASA Data Reveal Major Groundwater Loss in California”) knows well. And it's a relationship that David Shields explores in Reality Hunger: A Manifesto: “Urgency attaches itself now more to the tale taken directly from life than one fashioned by the imagination out of life.”

Shields’ primary claim is that the "novel qua novel is a form of nostalgia,” to be replaced by recombinant forms of writing, literary innovations that take their cues from musical remixes or media mashups.

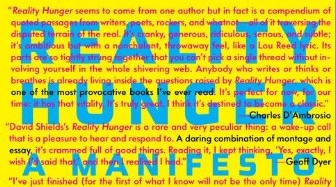

Initial reaction is mixed. While the book’s dust jacket is top-to-bottom blurbed with praise, strong reviews have lined up against it. James Wood of The New Yorker calls Shields’ sense of reality, “highly problematic.” “Deeply nihilistic,” concludes Michiko Kakutani, in the NYT. “Losing my appetite,” says Stephen Emms in the Guardian.

To be honest, I haven’t read Reality Hunger in the usual sense of starting with the epigraph (“Art is theft.” – Picasso) and continuing straight through until the final sentence (“Stop; don’t read any farther.”). In any event, my interest here is not the book's literary value but rather the social and political conversations to which it contributes.

One is somewhat theoretical: Sharing matters, for our learning is the sum of all we have absorbed from a long history of others, plus the extra that we have added. Another is utilitarian: Innovation and creativity can be stifled by excessive reliance on patents and copyrights.

My colleagues and I made a similar case in our own manifesto, a 2004 comic book:

Who owns the writings of Plato or the equations of Einstein? We all do. These strands in the tapestry of human learning are part of our "public domain." … Concerned that the public domain continue to grow, our nation's Founding Fathers instructed Congress "to promote the progress of science and the useful arts" by offering short-term monopolies as rewards. These are the tools that we know as patents and copyrights.

On the utilitarian side, some recent attention has focused on patent law and energy innovation. U.S. Secretary of Energy Steven Chu supported the need to “share all intellectual property, as much as possible,” and the U.K.’s Chatham House issued a report on “Who Owns Our Low Carbon Future?” An Eco-Patent Commons, collects contributions from business leaders like IBM, DuPont and Xerox; and the Global Innovation Commons offers a country-by-country list of available innovations in key areas like solar cells, water pumps and soil management.

Reality Hunger speaks to this broader cultural zeitgeist. Perusing its numbered epigrams, meditations and anecdotes, I occasionally thought of it as a personalized successor to another manifesto, The Cluetrain Manifesto, which, back in the 1990s, hailed the Internet as a democratizing force in the marketplace of ideas.

“Conversations among human beings sound human,” assert the Cluetrain authors. “Whether delivering information, opinions, perspectives, dissenting arguments or humorous asides, the human voice is typically open, natural, uncontrived.” As Shields relates, remixing with T.S. Eliot’s Prufrock: “I find I can listen to talk radio in a way that I can’t abide the network news – the sound of human voices waking before they drown.”

Subverting the media hierarchy with hyperlinks results in cacophony, say critics of “techno-utopianism,” like Kakutani. People are attracted to familiar worldviews, voices that offer a sense of belonging, shared among like-minded friends through platforms like Facebook. The consequence in the U.S. appears to be a loss of broader social cohesion.

Yet on urgent issues – including so-called environmental ones: food, water, energy, climate, oceans, forests and so on – old hierarchies have too often been found wanting. Progress depends on new alignments of interests and aspirations.

This is not utopianism, but pragmatism, a work in progress.

Originally published on People and Place, the Ecotrust blog.