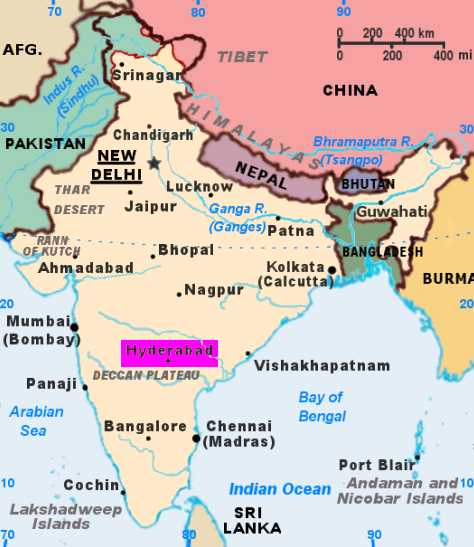

Two days before the launch of a global commons conference here in Hyderabad, India, drawing more than 600 people from 69 countries, a roomful of activists and scholars from across South Asia found that even in this controlled environment, unity is not so easy.

Playing a theoretical game called “Win All You Can,” these seasoned advocates of the commons — generally united in their efforts for sustainable ecologies and socially just economies — locked their minds and wills in a losing effort to protect a hypothetical commons.

Flocking to this south-central Indian city of eight million from all corners of the globe, this diverse grouping of academics, policymakers, and organizers aims to protect and expand a dizzyingly diverse ‘commons’ — pastoral and forest communities, nomadic tribes, open grazing ranges, rivers, coasts, air, the Internet, legal rights, the world of ideas and more — that are under attack.

Convened by the International Association for the Study of the Commons (IASC) and the Foundation for Ecological Security, the Hyderabad gathering seeks to “sustain the future of the commons” amid the rising tide of climate change and deepening economic divides.

Back in the pre-conference meet-up, commons advocates were challenged to think collectively while being divided into competing sub-groups tasked with ‘winning’ points by either choosing the collectively beneficial word “rabbit” or the individual gain from “rat” – a choice that would garner points at the expense of other groups, and of the collective whole. Instead of scoring a potential high of 1000 points on behalf of a mutual commons, the group produced negative 160. Good thing it was a game.

Although these commons advocates understood that choosing “rat” would erode the collective winnings, some veered away from commons thinking in a risky gambit for individual gain. Even after group leaders consulted together and discussed improving cooperation for the greater good, some veered off course — corroding the collective’s sense of trust and common purpose.

The lesson was clear: individual profit came at public expense, injuring not only the ‘other’ groups, but the collective as a whole. Everyone lost.

“You can only get to win-win if you think in the context of a larger ‘We’,” explained K.V. Raju, of the Institute of Rural Management in the state of Gujarat. “Most of the collective action fails because we defer to our own sub-set of ‘we.’”

While the game was all in geeky, theoretical good fun, Raju warned, “If we are not able to do it here, where there are no stakes,” then imagine the real-world consequences of “getting advantage at the cost of others.” As the IASC convenes its 13th biennial gathering — its first in a southern hemisphere nation — evidence of this private-gain-at-any-cost mentality is as overabundant as the teeming dusty poverty on Hyderabad’s ferociously fast streets.

In the nearby state of Orissa, to Hyderabad’s northeast, ‘land grabs’ are proliferating — private, for-profit interests snapping up and tearing down forests to mine for coal and steel production. POSCO India, a top global steel firm, is constructing a massive manufacturing plant in a 3000-acre forest area, allegedly violating India’s 2006 Forest Rights Act.

Farther north, in the Himalayan region, residents hungry for modern convenience and technology “are all ready to sell out everything,” says a disillusioned conference attendee who works to protect common resources there. “I can count you 40 dams in Himalayas. I can describe them all to you. All built for these things, for this new lifestyle” defined by the ubiquitous cars and television sets which most Americans take for granted.

Charminar in Hyderabad

Charminar in Hyderabad

Meanwhile numerous conference attendees voiced concern over rising inequality and corporate political power in India.

“Land is no longer considered a resource for livelihood in communities,” said Action Aid’s Amar Jyoti, “but is a commodity for profit and speculation.” Government and private firms in India, he says, are taking lands from resource-dependent tribal areas to churn up biofuel production.

When I ask an Indian delegate over lunch whether the commons are growing or shrinking, he replies, “they are less and less all the time,” as private firms own more and more. The Indian government, adds Raju, “is more for private interests now than public.”

In a stirring keynote speech launching the global commons meet-up, India’s Minister of the Environment and Forests, Shri Jairam Ramesh acknowledged, “We are world leaders in talking about international inequality, but we are a bit shy talking about domestic inequality.”

While India posted a stratospheric growth rate of nearly 9 percent in 2010 — 42 percent of its residents survive on a meager $1.25 a day; 230 million of India’s billion-plus people suffer from malnutrition, and the United Nations World Food Programme ranked India 94th among 119 nations in its Global Hunger Index.

Even the commons conference itself cannot escape India’s dramatic contrasts. The gathering is being held on a lush, immaculate campus in the relatively tony Jubilee Hills neighborhood removed from most of Hyderabad’s scuffling throngs — its curling boulevards swept clean by groups of women with straw brushes.

As an American journalist visiting India for the first time (courtesy of a travel scholarship from FES), it’s impossible for me to ignore the contrast of being served banquets of sumptuous Indian food at a commons conference in a city and country haunted by mass under-nourishment.

We travel to the lavish inaugural event in large tour buses slicing through Hyderabad’s furious clog of mopeds and auto rickshaws, its emaciated elders and children clawing and pleading for a few rupees. Beyond this dusty maelstrom we enter the inaugural by passing through a metal detector to enter the finely hewn lawns for tea and pastries while awaiting the arrival of dignitaries.

##

Christopher D. Cook is an award-winning journalist and writer who has written for Harper's, The Economist, Mother Jones, The Christian Science Monitor, and elsewhere. He is author of Diet for a Dead Planet: Big Business and the Coming Food Crisis. See more of his work at www.christopherdcook.com.