This short story was originally published in The Fabulist, "a new home for fables, yarns, tall tales, weird fiction, magic realism, and literary fantasy & science fiction."

When I was a kid, there were no canals, no vaporettos, no peacekeepers.

This year, we’ve seen Mutual Aid in Motion.

From scaling sharing hubs to Mutual Aid 101 trainings, we’re helping communities build the tools they need.

Every dollar fuels lasting resilience – proving that when we move together, we all move forward.

That San Francisco seems exotically technicolor to me now, like one of those planets the Enterprise visits that seems just like Earth but isn’t Earth at all, for reasons that are never explained — like that one when Kirk lands on the planet of children where disease kills all the adults.

I guess I was about ten when I realized that I, and everyone around me, had gotten on an Enterprise that took us from one Earth to another.

For a long time, everything was weirdly wrong, like the water on the streets and the bodies in the water. The adults were scared of the water and the bodies, but we kids loved the way things fell apart and turned the whole city into a playground.

But then we got old and the new San Francisco became home and the old one seemed to glow just a bit in our memories, and everything that had been strange got dull.

I keep searching for strangeness. I guess that’s why I played the game. They say it’s an escape, but I think in gamespace, where we strip away the meat, you can see what people really are.

* * * * *

He came over the foothills like a monument to himself: eyes the color of ambergris, skin of brass, tall as an adolescent elephant. Centaurs were rare that year; none of us had ever seen a creature as beautiful.

His name was Nessos.

He brought treasure — silver coins and gold chalices, glimmering gems and singing seashells — carried in twin parfleche panniers slung across his back. His only other dress was a cuirass and a feather-lined scabbard, from which sprang the gold pommel of a broadsword.

I need a clan, he said. Yours will have to do.

Across the granite slab at the center of our encampment he spread his loot, and offered his sword in our service.

We talked it over in the bark-covered longhouse.

He’s pretty, said Panpipe, one of two griffins in Chancre Clan.

He’s rich, said Oropher, an elf, and our chief.

He’ll be good in a fight, said Cray, who was, for some reason, human.

* * * * *

I had to pee. I had thought before about keeping a jar by the desk, but I didn’t want my mom to find it.

Jin, you there?

Yo.

The new guy’s registered as Philip Arnold, which sounds like a bullshit pseudonym. I’m googling.

I’m trying some other stuff.

I got nothing. You?

I got an IP address, a host name, and a location.

Oh, yeah? Where’s he live?

San Francisco.

No shit. Maybe he’s a neighbor.

Why does he want to join us?

Credit: Kevin Buckstiegel

Credit: Kevin Buckstiegel

I turned down the intensity of the wajang and the world seeped in past the gamespace. In the distance I heard a vaporetto chug down the canal. My stomach growled. I still had to pee.

I was still capped, still half in the gamespace; overlaying the sight and stench of my bedroom, I could smell the bark and feel the close, humid air of the longhouse.

* * * * *

In retrospect it’s obvious we shouldn’t have taken him in, but at the time it seemed like a good idea.

Truth is, we hadn’t won a battle in thirty days, and thieves and raiders were nipping at what treasure horde we still had. All we could do was man the earthworks, spears in hands and claws, and hope the gods would be kind that night. We needed new blood and a new sword.

As we voted to invite Nessos to join us, Golub raised the alarm. We raced from the longhouse where we’d been meeting, Nessos falling in behind.

We saw in a moment that a huge pack of human nomads were streaming into the valley like hairy, two-legged ants.

You’re in, Oropher told Nessos over his shoulder.

Just in time, I see, said Nessos.

We braced ourselves at the ramparts for the assault, staring down into the yellows of a hundred wild eyes, but Nessos didn’t wait. With a roar, he charged over the earthwork and thrust his sword through the lead raider’s lungs.

The next raider jabbed at Nessos with a spear while a third, scimitar held high, looped around to his rear.

Nessos kicked back and sent the third man flying into the air and over the earthworks, his neck broken and his ears bleeding.

The spear nicked a foreleg, but Nessos was already pushing backward, sword slashing down. His well-muscled, brassy reach was longer than the spear’s, and the man fell to the ground with his skull split and spilling brains.

We shouted and cheered and charged over the earthworks, taking the fight to the nomads.

Sure, it was lousy tactics. We were outnumbered. We should have dug in and let the raiders wear themselves out on assaults.

But we were sick of hiding behind piles of dirt and though he’d only just joined our clan, Nessos seemed to sense our mood.

Cutting and stabbing and slashing, blood and brains and bowels: it’d been many months since we’d had so much reckless fun in a fight.

In ten minutes the nomads were retreating into the foothills, harried by our arrows. Swords aloft, we jeered at their backsides and Nessos pranced at the center of our little mob, metal flanks shimmering with sweat, grey eyes haughty and fierce.

* * * * *

Take a look at the bookie sites.

Anyone who took the points made a pile.

We’ll be the underdog for a while yet.

Let me check my account … nice. Thirty thousand nue yuan.

I can buy my girlfriend something.

You have a girlfriend?

My mom is calling. Gotta uncap.

I took the glasses off and uncapped. My mom really was calling.

And now I really was hungry. Starving.

I delicately took my coffee cup down from my shelf, careful not to slosh the amber liquid; I took it across the hall to the bathroom and dumped it in the toilet.

Downstairs, Mom was in the kitchen burning water. She was wearing the sleeveless housedress that made her look like a bag lady.

“Hello dear,” she said. “Playing your game?”

“Yep. We won a match.”

“That’s good,” she said. “You know, Janis says that the government is holding social security this month.”

“Hmmm.”

“So we’ll need the money, sweetheart.”

“OK.” I took a seat at the table and read the back of a cereal box.

Win a free trip to the moon! it said. Send us 1,370,000 boxtops and we’ll send you and a friend to Moonbase Alpha!!!!

“I wish you’d bring some of your game friends to the house.”

“Most of them live in China or Korea. Gaming is bigger there.”

“I don’t see how you can let all those little robots into your brain.” Mom took a bowl of green beans out of the microwave. “Isn’t it uncomfortable?”

“Mom, you don’t feel the nanobots. I do get a little tingle when I cap and enter gamespace. No big deal.”

“What about all that fighting? I watch your games on the screen. It looks like you get hurt.”

“Nah,” I said. “You feel the blows, but even the bad ones are no worse than a slap.”

“Well, better that fake fighting than the real thing. I’m just glad you were never drafted, sweetheart.”

“I was too fat to take.” She knew that, of course, but I always felt this weird compulsion to say it aloud.

“More of you to love,” Mom said, and winked, which for no reason irritated me. She dished sausages onto a plate.

* * * * *

We repelled another raid, then two. We fought a larger neighboring encampment to a standstill, just on a wager.

We accepted two new members, a human archer named Ash and a gigantic carnivorous rabbit named Henry.

Feeling safer and stronger and braver, we ventured out to the Bastinado Archipelago on a quest for a set of bronze pannikins that would fill with any liquid the owner requested, strictly to enhance our reputation.

We formed a party of six, including Nessos, and set out for the island of the owner of the pannikins, a wizard called Dingledoom.

In the fight up to the top of the wizard’s tower, all of us were slain by orcs save Nessos.

The tale of his victory over Dingledoom became the stuff of gamespace legend.

In the center of Dingledoom’s lair there sat a cast-iron caldron into which the wizard could look and see the future. Rather than fight the wizard and orcs head on, Nessos offered to allow the wizard to turn his brass body into a statue if the wizard looked into the caldron and saw the centaur beheaded. If he saw Nessos intact, Chancre Clan would get the tower.

Oh, oh, oh, said Dingledoom, a malevolent gleam in his eye. I get it. A paradox. If I see you headless, you win, and you respawn elsewhere and still get my tower. You’ll probably cut your own head off, you yellow four-legged fiend. Well, I’ll take that wager, centaur!

With a shout of triumph, the wizard cast his most powerful protection spell across the room and over Nessos, who crackled with supernatural glamour.

Ha, ha! cried the wizard. That spell is so strong, you can’t even cut your own head off. Soon you’ll sit outside my door, a doom-laden forewarning to any cretins who’d dare steal from Dingledoom! Orcs, seize him, but harm not one hair on his yellow head!

As the pack of surviving orcs rushed into the lair, Dingledoom leaned eagerly over the caldron. Everyone watching the match saw a scarlet mist rise and we knew an image was forming. We saw the eyes of the wizard widen.

Nessos crouched backward on his hind legs and pushed off. He flew, magnificent, brass flanks shimmering, across the lair and over the caldron, so fast that the wizard hand’t time to lift his eyes. Nessos’s broadsword flashed out. The wizard’s head, mouth agape and eyes alarmed, flopped off the neck and into the caldron’s hellbroth.

Nessos landed on a cherrywood table littered with beakers and goblets, which he completely flattened. The pack of twenty orcs, green and grunting, circled him, but Nessos, cloaked by the wizard’s protection spell, made short work of the lot of them; the audience only saw his sword rising and falling around a bubbling sea of helms and spearpoints.

Soon, the wizard’s lair was painted black with orc gore, limbs and torsos and ugly green heads gloriously scattered across the floor.

Nessos raised his own sword to his neck. The protection spell had been worn down from the orcs’ blows and was now insufficient to protect Nessos from himself.

He whirled around, body curved, hooves at a gallop, and with one quick clanging stroke, he took his own head off. There was no blood; Nessos was fashioned of solid brass.

At that very moment Dingledoom stumbled back into the lair, having respawned (we later learned over ale) at the other side of the archipelago and flown as fast as his magic could carry him back to his tower.

Argh! he cried out, seeing Nessos’s brass head rolling on the ground. Ach!

Nessos wasn’t there to enjoy the wizard’s agony, having respawned at the other side of the continent. He’d sacrificed himself, if only for a moment, for the good of the clan.

And that’s how Chancre Clan, having set out to steal a few magic cups, gained a wizard’s tower and all its treasures.

And we owed our victory to Nessos, the centaur in brass.

If some had doubted him, they wouldn’t anymore.

* * * * *

“Mom, we won a big match.”

“Oh, I know dear. I placed a bet on your little group.”

“What?! Oh mom, you’re family. That’s not legal.”

She looked hurt, her lower lip sticking out. “I placed the bet under Nancy’s name.”

“If the gamemasters find out, I’ll never make the next level!”

“Sweetie, you’re twenty-five years old. Time to grow up. Everyone cheats once in a while.”

* * * * *

We broke camp and moved the entire clan to the wizard’s keep, re-dubbed Chancre Tower.

It turned out to be a damp, dim, and dirty residence, but we didn’t care. Though the victory over Dingledoom had been a kind of mishap, it puffed us up and raised our sights.

More creatures came from across the continent, coming at a rate of one a day on coracles and rowboats, petitioning for membership.

We started getting choosy.

* * * * *

Did everyone see the write-up in the Sing Tao Hourly?

No! Send me the link.

We made the bottom of the games page. The headline is: Underdogs no more! Chancre Clan comes out of nowhere to beat Dingledoom.

I see Jin and Kian get quoted.

Very cool.

* * * * *

In no time we were planning a raid on a sandstone castle in Hruba Skala, where, it was rumored, a baldanders kept a magical book that Columbine Clan needed to complete a quest.

We’d get the book and sell it to Columbine Clan, who said they’d swap it for a team of fighting pachyderms they’d won in a parlay.

We fancied we’d need a team of fighting pachyderms, though we didn’t give much thought as to how we’d feed them on a desolate islet, or even get them over the water.

We met on the black pebbly beach, since there was no space in the tower large enough to accommodate us all at once.

What’s a baldanders? asked Ash, leaning on his bow.

A monster whose name means ’suddenly different,’ or somesuch, replied Oropher. You never know what form a baldanders may take. Have any among us encountered a baldanders?

None had.

I deem this a job for a team of two thieves, said Oropher, who always favored stealth.

Nay! Turl said. The goblin tells us that a spell protects the castle from thievery. If we know nothing of a baldanders, we should go in strength, and take its castle by force of arms!

Why can’t Columbine get the scroll themselves? asked Nessos.

Oropher smiled. They tried already and they were beaten, he said.

If we could win this island, Nessos said, we can win a mere book.

We debated and in the end agreed we could do better than Columbine Clan, which had a reputation for choking in the breech. As night fell we haggled and planned and drew straws.

The next morning, thirteen of us set out to cross the gamespace to Hruba Skala.

On the way our little band was ambushed once in Brownhills by brigands and once on Mount Fasnacht by the dragon Winifred, but we slew all the brigands and we bought off the dreaded Winifred with a lindy hop performed by Turl and Cray.

* * * * *

That was humiliating. I can hear the gamemasters laughing at us.

You can’t beat a dragon.

Not with what we’ve got.

Get yer gamefaces on. Here comes the rock city.

* * * * *

The castle was carved from one of the sandstone columns, taller than Chancre tower. It appeared to be abandoned, the windowless holes dim and lifeless, the crenellated peak empty of guards. The cold wind blew and leaves swirled around our legs.

We smelled something burning, far away.

Credit: Bored Grrl

Credit: Bored Grrl

Let’s charge it, said Cray, waving Turl’s dirk.

Oropher scratched his delicate chin. I don’t know. I’m not sure that I like the looks of this.

Oropher, you must be bold, said Nessos.

We’d noticed Nessos testing Oropher is niggling ways; many of us had guessed that Nessos would soon challenge Oropher for leadership of the clan.

You go first, said Oropher. Come back and tell us what glamour guards this castle.

Nessos snorted and rode up to the oak door at the base of the castle. He drew his broadsword and used the pommel to knock heavily at the door.

We waited.

No answer, said Cray. No magic.

Not yet, said Oropher.

Nessos swung the unlocked door wide, and was the first to step in.

You two stay outside, Oropher said to Pythy and Panpipe. When we reach the roof, we’ll fire an arrow into the air. When you see that, come up. In the meantime, keep watch and stay alert.

The rest of us followed Nessos, swords drawn. We filed into a stone-walled anteroom draped in rotting tapestries, with sticks of furniture scattered across the stone floor.

A black spider sat in the corner, spinning a silver web.

Cray prodded the spider with the dirk; the spider skittered to the center of the web.

Spider, he said, does a baldanders live here?

A baldanders? squeeked the spider. What’s a baldanders?

Don’t play with me, arachnid. Cray wiggled the tip of the dirk.

Don’t hurt me! cried the spider. I’m just a little spider.

Oropher slapped Cray’s shoulder. The spider can’t help, he said.

If there’s no baldanders here, said Cray, this insect should know!

He snatched at the spider and caught her in his hand.

Ouch! he cried, hand flying open. The spider flipped to the floor and scampered into the folds of tapestry. That little beasty bit me!

Serves you right, Oropher said. Nessos, you’re still on point. Why don’t you climb the stairs?

Gladly, said Nessos. He trotted to the steps, carved from the very stone. The rest of us followed.

Oropher released a will-o-the-wisp from one of Dingledoom’s scrolls, and it cast a soft green light up the stairwell.

I don’t feel so good, Cray said.

You can be in the middle, Oropher said. I’ll take up the rear.

We fell in single file and Cray took a place between Golub and Henry.

The stairwell was steep, dark, and twisty; moment to moment we could see only the comrade on either side.

The stone glowed green in the light of the wisp and our faces took on the pallor of frogs’ bellies.

I don’t like this, Cray said in the darkness.

You were only too ready to charge in a moment ago, said Golub, whose glowing plate-sized emerald eyes could see in the dark.

I don’t feel … hey! Golub, you’re turning into an orc … Golub’s gone! Watch out!

Cray, what are you …

We heard a sword slash chain mail and suddenly Golub cried out and gurgled. He fell backwards into Ash.

Another orc, another orc! shouted Cray. He put one foot on Golub’s stomach and pulled the dirk out of the dead creature’s chest; with his free hand he drew his sword.

Cray, stop! cried Oropher, pushing his way up the stairs.

Ash raised his bow to deflect Cray’s blade, but Cray split the bow in two and drove his sword into Ash’s throat, both his hands pushing on the pommel.

As Ash slumped to the wall, Cray straightened and gasped. Blood flowed from his mouth. He tumbled on top of Ash, a dagger in his back.

Henry stood over the bodies, his pink ears drooping in the green light.

And our will-o-the-wisp flared, and blew out.

* * * * *

What the hell?

I swear my gameface saw them turn into orcs.

Dude. What the hell?

The spider’s bite must’ve done something to him. Released a virus that affected his gameface perception.

That’s new.

You shouldn’t have been messing with that spider thing. Isn’t the baldanders a shape-shifter? The spider could have been the baldanders.

I thought a spell had teleported them out and put orcs in. I saw that happen once.

You sure shouldn’t have just started stabbing.

Look, I didn’t know. Maybe I panicked a little.

Well, I don’t know if you should come back to the clan.

Hey …

Anyone know why Nessos never calls in?

Put your guard up, guys. We’re in another room.

Mom knocked on my door. I chinned out of the call and turned the wajang down low. The darkness of the stairwell lifted to reveal my bedroom.

“Come in,” I said.

Mom walked in, wearing the pink housedress.

“Sweetie, I thought I should let you know.”

“Know what?”

“Well, I put a lot of money on this match.”

“Mom!”

“Your group is doing so well.”

“Jeez, mom. Jeez.”

“Just try not to lose, OK, sweetie? We need the money.”

* * * * *

Grab the hand of the man in front of you! shouted Oropher. Keep your weapons ready and keep walking. When we get to the next room, I’ll spark a torch.

We ascended in total darkness. The steps ended; the floor leveled and we felt a breeze and we heard our footfalls echo.

I’m lighting a torch, said Oropher.

We saw a spark, two, a short torch flared. Two torches.

And each of us was suddenly two.

Oropher stood beside his double, which held a second torch. Each of the rest of us — Pliny and Henry, Flay and Krake, Harald and Rebus — faced his twin.

Henry confronted a second carnivorous rabbit, its left fang nicked in the same place; Pliny faced another dwarf who raised his axe at the instant Pliny raised his.

They’re Fetches! cried one of the two Krakes.

* * * * *

What’s a Fetch?

It’s a Scottish legend. A double who comes to fetch men to their death …

And women.

I fought one once on Mount Fasnacht.

I know which one I am, but I can’t figure out which is which for the rest of you.

We’ve got no choice. Kill the Fetch before he kills you.

* * * * *

When the hacking and slashing and stabbing had ended, the stone floor was slippery with gore and littered with limbs.

Oropher’s torch lay flickering on the ground near Henry’s right arm, and the matted fur started to smolder.

Nessos still stood, and so did Oropher. The rest were dead.

How do I know you’re not the Fetch? Nessos said to Oropher.

You don’t.

We understand each other, Nessos said. He picked up the hem of Krake’s cloak with the tip of his sword, grabbed it with his other hand, and proceeded to wipe the blade clean.

* * * * *

How come this Arnold person who is registered as Nessos never calls in?

Can we hack the gamesystem and get a number?

I’m on it.

Let’s see if we can’t get Philip Arnold on the call. Then we can find out if Nessos is real.

There’s heavy betting. People are watching us.

Too bad we look like idiots.

* * * * *

Oropher and Nessos started again up the stairs, led by the torch.

They crossed two more rooms. One was filled with more rotting furniture and tapestries; the second was an armory of doubtful usefulness.

Back in the stairwell, light grew and shadows formed and sharpened, and soon the two stepped out onto a garden on the top of the castle.

The ground was covered with a layer of thick, black dirt, from which grew foul-smelling plants, some white, some black. The plants thickened and clustered around a statue that stood in the middle of the courtyard, carved from rain-worn sandstone.

It had the head of a satyr, the torso of a man, the wings of an eagle, and the tail of a fish. A stone book grew directly from its hand.

From a barely perceptible belt hung a sword. It stood on a mound of masks carved from sandstone, each of the faces individual.

Most of the faces appeared to be terrified.

Though the space was, like the other rooms they had visited, only as wide as six men laid end to end, the walls reached just as high.

A gangway built of wooden staves ran around the wall near the top, with crenels carved into the walls.

These are mandrakes, Oropher said, peering at a black-leafed plant. Crush them and they start screaming. The scream drives you mad.

Perhaps the book is kept in the room we left, Nessos said.

We need assistance, Oropher said. He pulled his bow off his shoulder and drew an arrow. I’ll call the griffins.

He released the arrow over the wall and into the air. They waited.

No one comes, Nessos said.

Oropher shot another arrow.

The wind blew keenly through the crenels, as if the castle were a giant whistling through his teeth.

Oropher crossed the courtyard and started to climb the mound of masks. The statue holds a book, he said. It’s stone, but maybe it’s the one we’re looking for …

He laid his hand on the brown skirt of the statue.

There was a groaning, which came from deep inside the stone.

The horned head of the statue moved and looked down; its hand went to the sword at its side.

Oropher tumbled back down the mound into a plot of mandrakes. The leaves of the plants shivered and screeched.

* * * * *

We have a problem.

No shit we have a problem.

I know who Nessos is.

No shit. Who is he?

She. I traced Philip Arnold to someone named Kirsty Takahashi. I have an address.

Let’s send her an email.

Well, here’s the problem. Kirsty T. is also registered under the alias John Slack. John Slack is the registration name for the baldanders that we’re fighting.

Oh, man.

It gets worse. Kirsty T. is registered in her own name as one of the bettors on this match.

I don’t even want to know who she put her money on.

No, you don’t.

Somebody tell the gamemasters …

* * * * *

The baldanders — for now we knew, this was the creature that guarded the book — drew the sword from its stone scabbard, the blade gleaming with sinister glamour.

With the sound of stone breaking, its feet — one a goat’s foot and one a vulture’s claw — left the mound of masks, and the baldanders advanced on Oropher, who thrashed among the screaming mandrakes.

Oropher clapped his graceful hands to his ears and turned his face to the baldanders, who descended like a landslide.

Nessos galloped across the courtyard, sword held high, and he dashed up the pile of masks, flakes of sandstone flying away from his hooves. He reached the baldanders just as it stepped into the mandrakes, crushing one flat. The pitch of the screaming rose. Oropher dropped his hands, teeth clenched, and plucked one of Dingledoom’s scrolls from his belt. He started to read the spell and glamour gathered around him like smoke.

Credit: Tina Manthorpe

Credit: Tina Manthorpe

Nessos rammed the baldanders head on, heedless; his blade snapped into three pieces against the sandstone.

He rebounded away and into the mandrakes, falling on top of Oropher.

Now Oropher screamed, his mouth a knife wound, the scroll flipping into dirt, but the mandrakes drowned out his voice.

The blade of the baldanders sheared the air and cut flesh and brass with a single stroke.

* * * * *

That’s it. Match over.

That was a nightmare.

We killed each other. What a bunch of idiots.

Where’d everybody respawn? Let’s get the rest of the clan and go back.

Look, you know, I think I’m going to take a break.

Me, too.

I might try to find another clan.

Hey, don’t do that. We were good.

No, we weren’t.

We had fun.

Some. But we didn’t make much money. I need to make money.

Guys …

* * * * *

I stripped off the glasses and uncapped. I looked at my hands.

Shit.

I turned them around and laid them down on the wajang. It was a white dome, no wider than a plate, with three cables and a wire snaking out, the EEG skullcap lying where I had placed it.

Ugly on the outside, pretty on the inside. I lived half my life inside.

Credit: Jamison Wieser

Credit: Jamison Wieser

Outside it was getting dark. Rain clattered against the window. I wondered what was in that damn book that the baldanders carried. Maybe it was a probability-generating AI like Dingledoom’s caldron, which told the entire story of the game, from its very beginning to the very end, when the players were all uncapped and the servers were shut off.

Anyone who had that book would know the future of gamespace: who to rob, what to say, where to go. They’d make a killing in meatspace. They’d be richer than Gates.

I stood up and stretched. My back was killing me from sitting for so long.

I heard the telltale floorboard creak outside my door.

“You can come in, Mom,” I said.

The door opened. I could see her hand on the doorknob but the arm disappeared into the shadow of the hall.

“I’m really sorry,” I said.

“I’m … I’m not sure what we’re going to do, sweetie.” Her voice seemed heavy.

“I think the clan is breaking up.”

“What will we do?”

“I’ll probably buy a new gameface, maybe a human this time, and he’ll enter some tournaments. That’ll make me a little bit of yuan.”

“No, honey. What are we going to do? I needed you to keep winning.”

“Did you lose a lot of money?”

She didn’t answer and raindrops slapped the window. Then the door opened and she shuffled in.

“Maybe you should look for a real job … ” she said, not looking at me.

I felt smaller. A lot smaller.

“Gaming is a real job!” I shouted, and we both jumped, both scared.

I stood up and grabbed my coat from the bed. I turned to the desk, got my glasses, and put them on.

I felt the tingle and my icons popped up in front of me. “I’m going out. Don’t wait up.”

* * * * *

Outside on the stoop it was cold as well as raining.

I zipped up the coat and stepped onto the sidewalk. All the houses were dark; only about half of them were inhabited. Our neighbors had been moving away for years, even before the war.

I still got emails from Jorge, who’d moved to Vancouver. He had a good job as a bioprogrammer. He had friends and a girlfriend.

I walked down Cortland to the Mission Canal and waited for the vaporetto. In the shelter I studied a Sony Wajang ad, with a picture of Kai Wing giving the thumbs up and saying, When I play, I play Sony. Wing was a top-level player in a game called Star Destroyer.

I’d never played it, but I did see a couple of his matches. How much did Wing make for an ad like that? I looked it up on my glasses. Two million. What would I do with two million? Move to Canada, probably. Hang out with Jorge.

Across the canal I saw a squad of Korean peacekeepers, their blue helmets and slickers gleaming in the rain.

They smoked and didn’t talk to each other, not seeming to care how wet they got.

I took the vaporetto into the Mission and transferred at the 24th St. Pier to the forty-eight bus.

We groaned up to Twin Peaks, past the game bangs, with hapa teenagers smoking outside, and the dim bars and pawn shops.

When we crossed Castro the shops and restaurants brightened; there were more people on the streets and no peacekeepers.

I saw one bombed out Victorian, probably hit by a mortar, but otherwise all was intact.

I got off on Grandview and found that the rain had stopped. It was bright and clear, the way it can be after rain, when the moon is full.

In the space between two houses I could see the canals of San Francisco stained by streetlights and the island neighborhoods sitting like shipwrecks on the water. I could even spot the ruins of the Bay Bridge and I remembered Sundays when I was a kid, when we went to Fruitvale for brunch at Aunt Katie’s place.

I checked my glasses for the address Jin had found in the gamemaster system, and slowly walked up the wet street, peering through the dark at the numbers on the houses. I quickly found it, huge and white.

A single window on the second floor was lit yellow; the rest of the windows were dark.

I looked around. It was a rich person’s neighborhood — no one lived in a cooperative here — but even so, a quarter of the houses looked abandoned. I noted that the house directly across the street was one of the empty ones, its windows boarded up, weeds growing in the narrow lawn. There was no one else on the street.

Trying to look casual, I walked across the Takahashi lawn and around the back of the house. No light snapped on, no alarm went off. In the back yard I found a rock garden, with a few short, twisted trees, two benches, and a patio set. I walked up to the sliding glass doors and peered into the living room.

All the furniture was as white as the house and covered with plastic, with an ancient plasma screen filling up half a wall. I tried the door; it was locked, of course.

As I walked back over the rocks, now less careful, I saw a garden gnome sitting under one of the short trees.

I detoured and picked it up and tucked it under my arm. I left the yard and walked down the street back towards the bus.

* * * * *

I admit it: I started watching the house.

The Takahashi family consisted of a handsome middle-aged Japanese guy, a slutty looking blonde, and their hapa daughter, whom I pegged as Kirsty.

She was slim, eighteen or nineteen, with bright eyes and dark hair. I once caught her in the window of her bedroom in her bra, for about twenty seconds before she drew the blinds.

I recorded the image in my glasses. That kept me going for days. Sometimes, it still does.

Kirsty didn’t go to school and didn’t go to a job. She spent most of her time in the house, venturing out to meet friends in the Castro and on 24th St., where they did lunch and shopped.

All of her friends looked just like her: Hapa, pretty, slim, rich, with expensive AI glasses.

I followed her every day for a week.

On the last day I followed Kirsty to a bookstore on the Market canal. When she went inside, I sat on a bench in front of a cafe half a block away. I bought a bagel and fed most of it to the ducks that gathered on the banks of the canal and left white duckshit all over the parapet.

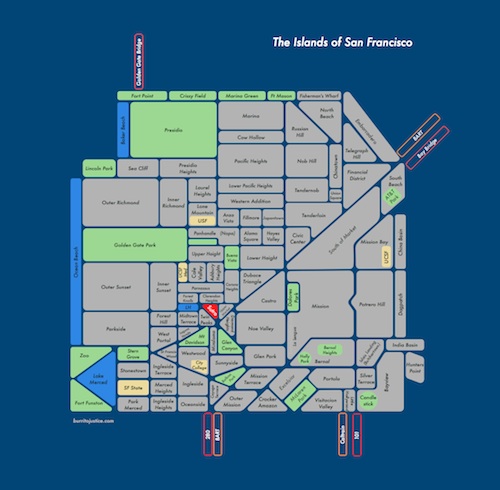

The Valencia Street canal in San Francisco. Source: Burrito Justice

The Valencia Street canal in San Francisco. Source: Burrito Justice

The sky was the color of slate. Kayakers bobbed near the bank as vaporettos chugged down the center of the canal, people leaning on the rails. I watched part of a Swords of Blakmar match on my glasses.

After a half hour I realized that Kirsty hadn’t come out. I admit I was a little bit concerned; I had been watching her so much that I’d started to feel protective of Kirsty. I turned off the glasses, threw the rest of the bagel to the ducks and went inside.

I strolled between the shelves, stopping to browse the science-fiction section; I picked up the 45th book of the Wheel of Time series, which had just come out. I kept moving to the rear of the store, keeping one eye on the entrance.

I got to the back and turned around.

When I rounded the corner into the self-help section, I almost walked over Kirsty, who was crouching on the floor. She yelped and jumped up; I stumbled back a few steps.

“Why are you following me?” she said, looking straight at me, fists clenched at her hips.

“What? I’m not … ” I said, not able to meet her eyes.

“You’ve been following me. I want to know why.”

“I, uh, do you play Swords of Blakmar?” I said. I thought: way to go, jerk.

“What? What did you say?”

“You know, the game. Swords of Blakmar? I play in the lower levels, but I’m working my way up. You might have heard of my clan … we got a write-up in Sing Tao … ”

“Do you even know how creepy you are?” Her voice shook and rose. “Do you?”

I could feel the other customers looking at us. I felt really hot.

“Listen, I just want to ask you … ” I raised my hand.

“Don’t fucking touch me!” she screamed.

Now I saw a clerk coming down the aisle behind her.

“I’m not … hey, at least I’m honest, I don’t cheat … ” I said.

“Are you OK?” The clerk asked Kirsty, standing just behind her.

She blinked at him, but didn’t respond.

The three of us stood there, Kirsty lowering her eyes to the floor.

Then she looked up again and she didn’t look angry or afraid.

“I got banned, you know,” she said to me. “From the game.”

“You broke the rules,” I said. “And our clan really tried. We were doing really good.”

The clerk shrugged and walked back up the aisle.

“Only because of me,” she said. “Do you know how hard I worked to build that gameface?”

“It’s true,” I admitted. “The centaur was cool. The baldanders might have been even cooler. It was really scary.”

“Thanks.”

She seemed almost shy as she said this, turning her eyes to the shelf, picking at a book.

“You were good at the game. You could have made plenty of money without cheating. Why didn’t you just fight your way through the levels like everyone else?”

“Because I’m not like everyone else,” she said. “I’m better.”

She turned and walked away.

It made me mad, the way she just walked away.

“I stole the gnome out of your garden!” I bawled at her back. “I gave it to my mom.”

“You keep it,” she said, turning her head in profile. “I hated that creepy thing. Besides, it looks like you.”

* * * * *

Things got bad after that, I guess.

I was too discouraged to game for money — you could say I was depressed — and the government stopped sending social security checks.

Within a year, mom and I lost our house.

We spent a few scary nights sleeping on the banks of the Market canal, me hugging the wajang close under a wool blanket, until the city assigned us temporary housing in the Mission.

I applied for a job-training gameface, and they gave me one.

Pretty soon I was interning for the water department gamespace in risk management, helping figure out all the horrible shit that could go wrong in the city: earthquakes, flood, terrorist attacks, another invasion, thieves, a thousand different kinds of breakdowns.

I imagined each threat as a brass centaur, and I never dropped my guard.

You know what? I turned out to be good at the job. I got promoted from intern to assistant; a year after that, I was running my own risk scenarios in the municipal gamespace.

The pay was fine, and we were able to join a cooperative apartment complex on Corona Island, and Mom got so involved with the neighbors that she mostly left me alone.

When my risk unit came up with a proposal for neighborhood aquaponic greenhouses as a solution to the city’s water and food distribution problems, the department assigned me to launch a meatspace pilot project on Corona.

Photo by Tyla, from the Shareable.net article "Aquaphonic Transformation."

Photo by Tyla, from the Shareable.net article "Aquaphonic Transformation."

Pretty soon I was spending only half the day in the municipal gamespace; most of the time I was working with neighbors to build the greenhouse.

I learned how to use a hammer and screwdriver; I lost weight.

The first time we ate fish from the greenhouse tank in the coop kitchen, I looked around at my neighbors and realized that maybe I was helping make things a little bit better.

Which was weird.

I never went back to playing Swords of Blakmar. But sometimes I’d dream I was Oropher.

I was Oropher but I wasn’t in the gamespace; I was here at home on Corona, but bearing a shield and carrying a sword, brave and strange. And the people in the cooperative were my new clan.

* * * * *

I did see Kirsty one more time, five years after the Nessos debacle.

I was at Dolores Park with my mom. It was sunny and dry, for once, and we spread a blanket out on the grass in front of the lake and ate pickles and sandwiches.

Mom wore her bright flower-print housedress and a straw hat. After lunch she lay down and fell asleep spread-eagled.

I finished the new Dune novel I was reading on my glasses (Sandfleas of Dune, which in my opinion wasn’t as good as the last one) and got up to pee.

As I walked back to our spot I saw her, sitting on the bench at the top of the ridge that forms the southwest corner of the park.

Kirsty wore white shorts and a yellow T-shirt, pretty as she had been five years before, and she was looking at something far away, shielding her eyes with both hands.

She was incandescent with sunlight, sitting perfectly still, and of course I thought of the centaur and imagined Kirsty as a solid brass monument to herself.

At that moment I wanted so badly to see Nessos step into the muddy park, kicking up tufts of dirt and grass, sword drawn and gleaming in the sun.

The sunbathers would scream and scatter like the orcs and trolls they really are, scared and suspicious, and Nessos would rear and gallop and sweep through the park like a cold wind and cut them down with his sword and the grass would turn black with blood.

It’d be awful to see and I wanted to see it so badly.

Why shouldn’t something so beautiful and magical have the right to do anything it wanted?