At Popular Mechanics, Glenn Harlan Reynolds suggests that Haiti should remind Americans of the importance of self-reliance:

If you’re at the scene of a major disaster, it may be a long time before outside help arrives. But one person is sure to be there: you. And nobody cares more about helping you and your family in time of disaster than, well, you. So it makes sense for you to be prepared to take care of yourself—and look out for your neighbors—for some time afterward. That means having adequate stocks of food, water and basic tools on hand. (Experts say that Haitians should have had at least two weeks of food on hand, but of course many Haitians can’t afford to keep such reserves. Americans, generally speaking, can.)

Speaking as a parent living in an earthquake zone, I don’t disagree: everyone who can afford it should stock food, water, tools, and medicine.

But Reynolds’ stress on self-reliance strikes me as incomplete, and perhaps even neurotic in an especially American way. Because in the face of disaster, there’s another resource Americans should be stocking up on: a sense of community.

When Reynolds uses Haiti to trumpet the virtues of self-reliance, he is indirectly promoting the view that disasters bring out the worst in people–, that sharing goes out the window and hoarding is the only way we can survive.

This belief doesn’t stand the test of empirical reality. "It turns out that people rarely respond to disaster with extreme panic, recklessness, and selfishness," writes Lee Clarke, a Rutgers University sociologist and author of Worst Cases: Terror and Catastrophe in the Popular Imagination.

"September 11, 2001 showed that people are wiling to help out others during an emergency," says a report from the National Institute of Standards and Technology, one of the most thorough studies of a disaster I’ve ever seen. "These helpers often remained with the occupant in need throughout their entire evacuation, even though they were putting themselves at risk." If most people had panicked on September 11, the death toll would have been much, much higher.

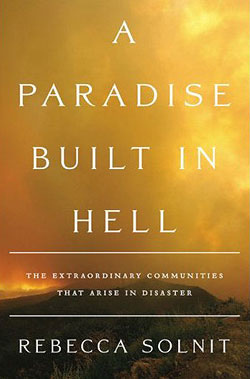

Pulitzer-Prize-winning author Rebecca Solnit goes further. In A Paradise Built in Hell: The Extraordinary Communities That Arise in Disaster

Pulitzer-Prize-winning author Rebecca Solnit goes further. In A Paradise Built in Hell: The Extraordinary Communities That Arise in Disaster, she describes how people struck with natural disaster are capable of pulling together and discovering new forms of community. As she tells an interviewer:

The disaster histories really caught me by surprise. I had a fundamentally positive and hopeful view, but this stuff was more so than I might’ve dared–here were major disasters in which, for example, a spontaneously assembled armada of boats evacuated 300,000 to 500,000 people from the lower edge of Manhattan in the hours after the Trade Center towers collapsed, boats going into that terrible cloud of uncertain danger in an evacuation no one directed and no one was ordered to carry out. It was the size of the famous Dunkirk evacuation of the Second World War, but that one took nine days (and was admittedly carried out under German fire). Not very many people even know about it, or understand how important a role the “Cajun Navy” of boatmen played in evacuating flooded New Orleans four years later–also an example of spontaneous, self-organized evacuators operating in circumstances they were told were hideously dangerous. They were rescuing people the media and government encouraged them to see as violent brutes. You start to see a century of such patterns and see that this is more encouraging than you might have dared to believe–encouraging also because most of that stuff about crazy looting panicking mobs in disaster is pure hallucination and slander. And that too is documented by the magnificent work of the disaster sociologists that opened up this realm for me, or rather that gave a stable substructure to the amazing first-person stories I also used extensively.

This history should cause us to view Reynolds’ advice in a different light: Sure, we should stock up on life-giving necessities, but not just for our own sake. It’s just as important, perhaps more, to work to build connections with our neighbors, community institutions, and resources that all of us can share in common. Those are the things, not privately held food and water, that make our communities most resilient. Indeed, I believe building community is the best way to prepare for disasters.

"We go astray when we assume that our dark side is our true, real, essential, natural side," writes Lee Clarke. "According to this view, the rules that govern social relations are luxury items, discarded in a disaster as one might shed a gold bar while trying to escape a sinking ship. But the truth is that our daily lives are built on a multitude of civilities and cooperative exchanges between people…And sure enough, when disaster strikes, people still routinely help perfect strangers."

Hat tip to Boing Boing for the Reynolds link.