UPDATE: We've summarized much of the series this article is part of in a new report, Policies for Shareable Cities: A Sharing Economy Policy Primer for Urban Leaders. Get your free copy here today.

Second units, cohousing neighborhoods, ecovillages, clustered “tiny homes,” collective houses – these are part of the important spectrum of possibilities for meeting our housing needs as the population grows, and as we work to dramatically shrink our housing’s footprint on the Earth. The need for new housing units puts incredible demands on our society. In the nine counties of the San Francisco Bay Area, for example, it is projected that we need more than 23,000 new housing units per year. Shared housing options can help us meet this need, and provide an alternative to endless urban sprawl.

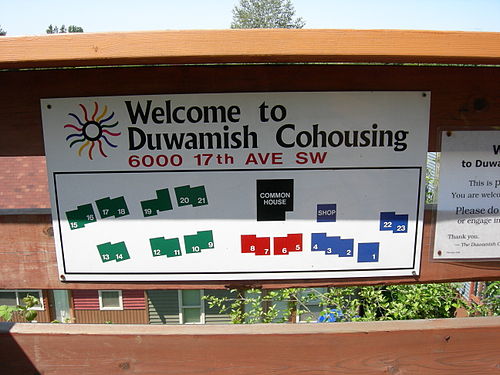

A guide to the Duwamish Cohousing project in West Seattle, Washington. Photo credit: Joe Mabel. Used under Creative Commons license.

There are many policies that cities can adopt to enable and incentivize shareable housing solutions. A handful of recommendations follow, and we encourage you to add more in the comments section below.

-

Zoning for shared resource living: Cities could increase allowable density, even in single-family residential areas, by recognizing that shared housing mitigates some of the impacts of density (less waste, lower energy needs, less traffic, fewer cars parked, etc). Yarrow Ecovillage and O.U.R. Ecovillage, both in Canada, received zoning approvals by asking their local jurisdictions to take into account the low impact the ecovillages would have in comparison to typical developments. Maitreya Ecovillage in Eugene, Oregon, and Bloomington Cooperative Plots Ecovillage in Bloomington, Indiana, are two communities that have proposed similar zoning in the United States.

-

Rethink parking requirements: Paving paradise should not be mandatory, especially because mandatory parking requirements are a huge barrier to shared housing. In Mountain View, California, the cost of one cohousing development significantly increased, due to the city’s inflexible requirement that the development provide 2.3 parking spaces per new unit. Cities could actually incentivize shared housing, car sharing, ride sharing, and public transit use by loosening requirements that each new unit be accompanied by off-street parking, and by finding other ways to ensure that street parking doesn’t become a nightmare. For example, a city could require that new unit developments be accompanied by a car-sharing plan or program, transit passes for residents, bicycle parking, and other infrastructure that enables residents to not own a car. Parker Place in Berkeley, California, is an example of one proposed development implementing such programs. Cities could also require residents of new units to pay higher fees for street-parking permits, since those residents would normally have incurred the expense of installing a new parking spot on the property.

-

Facilitate the addition of new units to existing homes: Accessory dwelling units – also known as ADUs, granny flats, in-law units, second units, accessory apartments – may provide the most important means by which we will house our growing population. In 2003, the California legislature passed AB 1866 requiring that cities adopt more streamlined policies for the permitting of ADUs. Yet, many city policies continue to make the building of such units cost-prohibitive, often due to steep fees for sewer and water connection, the cost of additional parking, and so on. These fees often build in the wrong incentives, by charging based on the number of units added, rather than the square footage added or the ecological footprint of the addition. For example, you might be able to build an audacious new parlor onto your home with very few fees; but, if you want to turn that into a small studio apartment with a kitchen space and bath, you will have to face all the fees associated with becoming a two-unit property. It doesn’t seem right that our laws would incentivize “McMansion” lifestyles and disincentivize the creation of affordable units to meet society’s housing needs. To build in the right incentives, cities should adopt more streamlined permitting processes and more sensitive fee structures. One proposal is to set fees based on the green square foot of a project. Cities should also make the process more simple to navigate – for an example, see the ADU website in Portland, Oregon, and the ADU Development Program in Santa Cruz, California.

-

Encourage collaboratively developed communities: Inclusionary zoning is an important tool for ensuring a secure supply of affordable housing units; such laws often require that new developments contain a certain number of affordable units and/or rental units. At the same time, such laws sometimes present barriers to the creation of cohousing units. For example, in Oakland, California, if a group of 10 people were to buy a 10-unit building for the purpose of creating cohousing for themselves, they might be required to create a certain number of replacement rental units in their building or elsewhere in the city. Such laws add significant costs to a project and can negatively impact the feasibility of resident-developed cohousing projects. Cities should make special exemptions for owner-occupied units that are cooperatively developed by the people intending to live in the units.

-

Allow for short-term stays: Many cities make it next to impossible for people to host short-term guests in exchange for money. For more information, see this article on the legalities of short-term stays. Cities should adopt more sensitive policies around short-term rentals, which would allow residents to off-set their housing costs, and would also give travelers an alternative to patronizing large hotel chains.

-

Remove restrictions on cohabitation: In many cities throughout the county, zoning laws still prohibit unrelated individuals from forming a household, and/or the laws set a cap on the number of people allowed to live in a unit. Such laws have presented barriers to groups that intentionally seek to live in a shared and/or supportive living arrangement. Mental Health Advocacy Services, Inc. has issued a set of recommendations for how cities can redefine family and occupancy standards.

-

Require that new developments meet shareability standards: The design of our communities can greatly impact the extent to which residents interact and share resources. Cities could require that new developments undergo a design review to ensure that new developments encourage interaction and sharing. For example, cities should either require or incentivize clustering of housing around central courtyards and/or the inclusion of common areas and common houses designed for shared laundry facilities, shared meals, community activities, children’s play areas, a wellness area, shared workspaces, and so on. In addition, cities should encourage more mixed-use developments which bring commercial and housing needs together in one place, reducing traffic and parking needs by allowing residents to walk to essential businesses and services.

-

Facilitate development of tiny houses, yurts, container homes, and other humble abodes: The tiny house trend is growing, as a lot of people adopt more humble visions of how they house themselves. What can cities do to enable widespread adoption of more modest abodes? First, it’s important for cities to recognize such structures as legally habitable; many cities have adopted International Residential Code requirements that a dwelling unit include a minimum of one room that is at least 120 square feet in area which would serve as a barrier to some of these dwellings. Cities and states should also grant permits for amenities such as composting toilets and grey water systems which help to avoid the huge expense of a sewer hook-up for such dwellings. Cities should also adopt more sensitive permitting processes that recognize that a clustered village of yurts or tiny houses should not have to jump through the same permitting hoops and pay the same fees as a subdivision filled with McMansions.

The playground next to the Common House at the Sunward Cohousing Community in Ann Arbor, Michigan. Photo is public domain.

To encourage more economically and ecologically sustainable housing, in general, cities should be thinking about sharing in all aspects of policy making. The recommendations listed above and throughout this 20-part series all enable communities greater access to shared resources – shared workspaces, shared outdoor spaces, shared kitchens, shared storage, tool-lending libraries, shared living areas, and so on. The more that each of us has access to shared resources, the easier it will be for our growing population to find contentment in more humble and sustainable housing arrangements.

How else might a city foster shareable housing? Please post your thoughts below and help us build this collection of policy proposals. Thank you!

###

Acknowledgments: This article was written by Sustainable Economies Law Center (SELC) Co-Director Janelle Orsi and SELC Intern Julie Pennington, with input from Golden Gate University School of Law student Dawn Withers, and ideas from from city planner Nathan Dahl.

This post is one of 15 parts of our Policies for a Shareable City series with the Sustainable Economies Law Center:

- Car Sharing and Parking Sharing

- Ride Sharing

- Bike Sharing

- Shareable Commercial Spaces

- Shareable Housing

- Homes as Sharing Hubs

- Shareable Neighborhoods

- Shareable Workspaces

- Recreational and Green Spaces

- Shareable Rooftops

- Urban Agriculture

- Food Sharing

- Public Libraries

- The Shareable City Employee

- How to Rebuild the City as a Platform