Below is an excerpt from Jonathan Salem Baskin’s provocative book Histories of Social Media.

Societies have been social since civilization began. It’s what societies do (hence the shared latin root socius, for “allied” or “friend”). Surely the first drawings on cave walls were born of some debate, and conversations about them likely followed. Human beings haven’t stopped jabbering since.

Are Facebook, Twitter, or YouTube really new? The technologies certainly are, but history provides antecedents for every behavioral, cultural, and commercial quality of social media. Crowdsourcing? Medieval villagers used it to learn about treatments for the Black death long before consumers submitted ideas for new flavors of soda pop. Engagement? 19th century industrial unions were planning activism in ways that make “friending” a product or service little more than a joke. Conversation? The Romans ran their governments with it, while the French Terror used it to murder thousands. Debate? People have jousted and dueled for centuries.

If you strip away the technology and its presumptions, you open up a rich resource of case histories that may better explain the dynamics, shortcomings, and immense opportunities for today’s social media.

Of course, technology is much more than an electrified cave wall; how a medium works has a great influence on what it communicates. For instance, Twitter’s 140-character limit dictates not only length but the substance of entries. Who would have ever imagined a hundred years ago the sorts of content shared on Facebook? Technology reveals uses that nobody could have foreseen, so it’s certainly both a causal agent and content contributor for change.

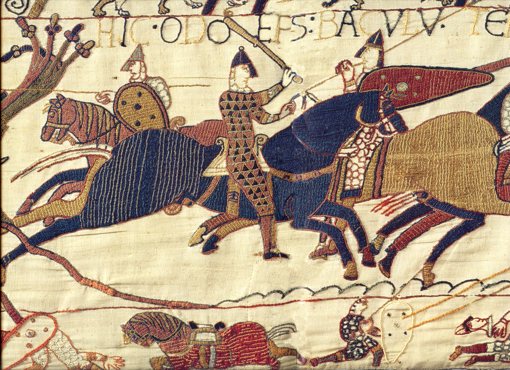

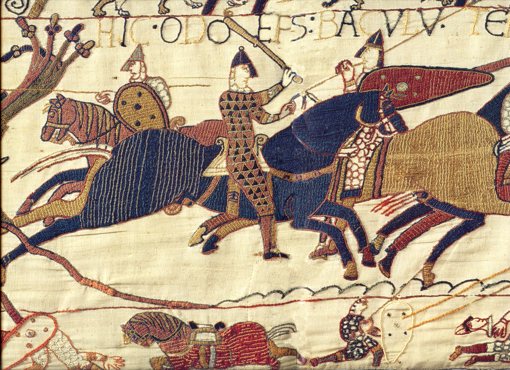

Yet “face books” have existed throughout history, whether as the Sears Roebuck catalog in the 1800s or the Bayeux tapestry in the 1000s. Networks have been with us for many centuries, built by roads, ships, banks, and even carrier pigeons before anybody experienced the internet, and communities were constructed in wood and stone before they were imagined in electronic bits. We will always communicate in new and different ways. To focus on technology is to highlight a transitory quality, and not the substance of social experiences.

Those experiences are more fundamental to how we think and live, and they make our past more illustrative and informative than any theory or perspective that ignores them. We simply can’t understand social media without delving into the histories of social experience. To understand our future we must first explore what we’ve done in the past.

Not many folks look at it this way, though. Most expert analyses see social media as a new phenomenon emerging from the phone hackers of the 1950s and, more directly, the electronic bulletin boards of the late 1970s. It’s accepted wisdom that the capacity for people to instantly send messages to one another dates back to internet relay chat in the 1980s, though today’s era of social media technology didn’t truly debut until 1991 when the World Wide Web was opened up to, well, the world.

While this recent history is interesting, it’s only a blip in the long continuum of social activity. Presuming the phenomenon’s uniqueness leaves companies and institutions without the benefits of context or perspective, and leads some of them to rewrite their entire business strategies to hopefully find purposes for social media technologies. This is a mistake, in my opinion. There are literally thousands of years of social behaviors that have been written into the ways individuals act and organizations operate. There’s a track record available to us of what works, what doesn’t work, and why.

How much of what we think is new is really just new to us?