Mutual aid groups were a lifeline for many during the pandemic. In the face of near-constant loss and uncertainty, neighbours and communities came together to create networks of food provision, emotional support, and more.

Emerging from the Covid-19 pandemic, The UK — like many global communities — remains an economically-precarious and socially-traumatised place. Adding insult to injury, we are now facing a cost-of-living crisis. A growing number of people are requiring help to secure adequate housing, food, and shelter. Now more than ever, the mutual aid groups that acted so vitally during the pandemic continue to be needed.

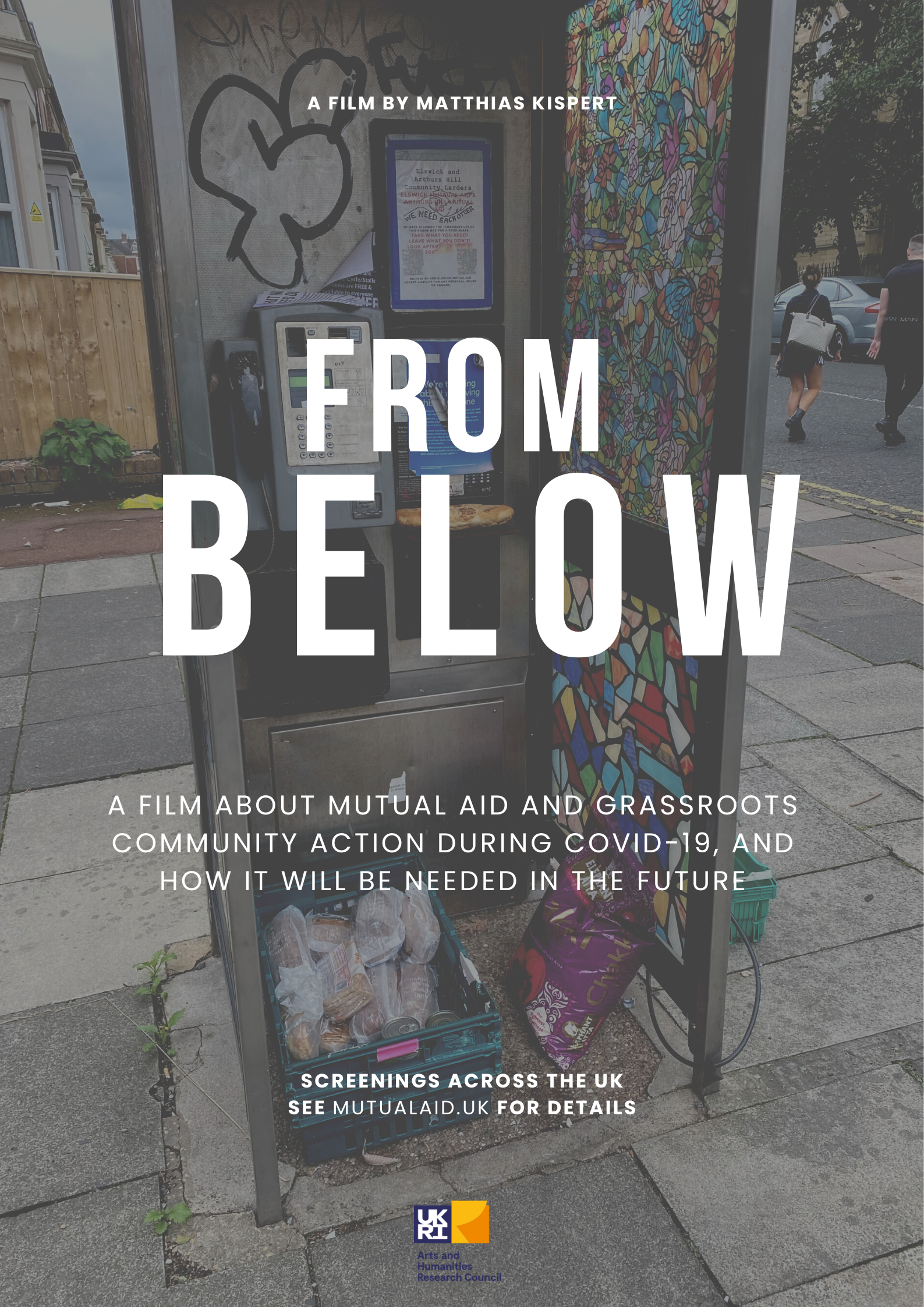

“From Below” shares an honest picture of the people at the centre of crisis care

From Below (2022, dir: Matthias Kispert), featured above, is a feature-length documentary film (now being screened across the UK) that showcases the human, emotional stories of the mutual aid phenomena. The film also highlights the ways mutual aid can continue to be used as a force for change in a post-pandemic future. The wider research that the film supports is an examination of the people at the center of these crises care mutual aid networks as well as the barriers and pitfalls they faced at the height of their practice.

Emotional burnout was the primary problem faced by many volunteers and organisers. Many of them expressed their exhaustion, explaining that the lack of time for self-care and (in some cases) inability to access necessary mental health services contributed to their fatigue.

In other groups, a lack of a functional space hindered their work, which made it difficult to pack bags and cook meals for sometimes hundreds of people. Lack of operational skills affected some groups: team leaders and members sometimes lacked co-operative and team-work skills, had little food safety experience or little financial expertise. Often important vehicles to continue working (such as a bank account to collect donations) were difficult to obtain due to the group not being recognised as an ‘official’ institutional form, i.e. a charity or community interest company.

Rejecting institutionalisation

Supporting the vital work of mutual aid groups means rejecting the assumption that their work must be executed in an institutionalised format in order to be effective.

In fact, our research indicated that it was mutual aid groups’ flexibility, malleability, and precisely non-institutional form which was their strength. During the pandemic, people were quick to identify needs in their local community, utilising intimate and ‘embedded’ knowledge of local provisions in order to better mobilise resources.

Schoolteachers and outreach workers knew vulnerable families by name and, as such, were able to share their information with mutual aid organisers who were able to directly provide them with resources. Activists maintained relationships with undocumented asylum seekers. Faith group leaders had intimate knowledge of the needs of their congregation. Residents knew which local community spaces had the correct facilities to be used as a distribution centre.

All of these organisers operated cooperatively, forming a cohesive, localized network of solidarity. If mutual aid groups were to be asked — or forced — to institutionalise their work would be hamstrung, affecting their ability to act swiftly and nimbly. Moreover, and perhaps more importantly, many mutual aid groups operate as political entities as well.

Embracing radical solidarity

It was a common thread among all the mutual aid groups that we spoke to while making “From Below” that the more people got involved, the more they became aware of the social and political contexts that made people vulnerable in the first place. Some said that they “had their eyes opened” to the unfairness of the benefits system, and were able to sympathise with people who they would otherwise judge.

These spaces brought together people from across class divides, creating spaces of learning, empathy, and in some cases, radical solidarity. Some groups even merged their food and social services provisions with political action, often referred to in the academic literature as ‘prefigurative politics’. Institutionalising these groups to become more like hierarchical charities would be entirely antithetical to their political rasion d’etre.

Institutions as peripheral partners

There are still things institutions can do to help mutual aid groups continue their vital work. In lieu of underscoring their processes or attempting to fundamentally shift their structure, ‘official’ institutions can foster trust and embeddedness between themselves and mutual aid groups through provision of financial remuneration.

They can also make spaces available for mutual aid groups (community centres, social clubs, kitchens etc.) and simplify grant application processes, introducing them to emergency funding in times of crisis. The implementation of national level policies (such as a 4-day working week and universal basic income) would also aid mutual aid efforts by providing organisers with the free time and vital emotional energy needed to do their work. These are just a few examples of what could be done. Our Manifesto for Mutual Aid provides a full list of our recommendations.

Mutual aid as more than crisis care

Whether we turn our attention to the pandemic, economic inequity, or increasing climate catastrophe, the reality is that we are living in the age of multiple crises. Mutual aid has proved over and over again to be the most effective form of support for many communities in precarious times, but its effect can stretch far beyond that.

As we navigate these compounded crises, it is time to not only acknowledge mutual aid’s ability to address the needs of those most vulnerable, but also support those doing the work of keeping these vital networks afloat.

This article was originally published on October 18, 2022 and has been updated now that the film, “From Below,” is publically available.