Today, 50 million Americans are uninsured, while millions more of us keep jobs we hate in order to pay rising insurance fees. Medical bills cause half of all bankruptcies and millions of evictions. Doctors often pay more attention to insurers than to patients, and America’s infant mortality rate ranks 34th.

Americans have been griping about medical insurance for over 100 years, ever since Teddy Roosevelt proposed a national insurance plan in 1912. Obamacare is already being diluted by insurers. But griping is a drag. Power is fun. Let’s take power. When corporate medical insurance ensures profits while blocking health care, it’s time to replace it. Not only this, but it’s time to quit waiting for Congress and take direct control of health care, starting in our communities.

Sixteen years ago, I realized that Congress would never extend Medicare to everyone because legislators are bought off by insurance companies. So I started a genuinely nonprofit health co-op in Ithaca, New York.

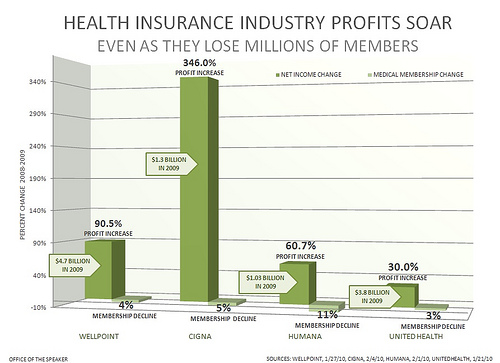

Health insurance companies enjoy healthy profits. Photo credit: Leader Nancy Pelosi. Used under Creative Commons license.

The Ithaca Health Aliance began when I set up a display in public places and said, “Let’s each pay $100 per year into a fund. As the cash pile grows, we’ll pay for an increasing variety of common emergencies like broken bones, stitches, and burns.” Medical emergencies are called “non-elective” care since people rarely choose to crack, slice, or burn themselves.

On the first day, we had $300. During the next several years, the fund grew gradually to nearly $1 million. We compensated our members for 12 categories of emergencies — anywhere in the world — to specified maximum amounts. Upon our modest surplus income, we started a member-owned free clinic. The co-op was not a pyramid scheme because the payment menu both expanded or stabliized with member enrollment. We could estimate how frequent these injuries would happen to our member base, then calculate maximum payments for each category.

The system proved itself so well that it was endorsed by Ithaca’s Chamber of Commerce, Health Department, county legislature, mayor, Health Planning Council, the chairman of the New York State Senate Insurance Committee, and by our members from 47 states. Though an outside-the-box plan, we were permitted to continue by the NYS Insurance Department.

Members elected a board of directors yearly, who decided when to expand payment categories and amounts. Every payment to members was listed on the website chronologically. We also listed every denial of claim (for categories not yet covered).

For the first seven years we grew steadily then leveled off to pay lawyers to satisfy NYS regulators. They agreed to allow us to continue if we enrolled only NYS residents. NYS has a law for minor medical plans (5422a).

Our potential to become a national model of genuinely nonprofit health security, within a community-financed health system, began to attract national attention. Yet co-op insurance is not a new idea. Eighty years ago, one third of Americans were members of fraternal benefit co-ops, like the Moose, Elks, and Odd Fellows. Members pooled pennies per week to build community hospitals and clinics, orphanages and old folks’ homes, and to pay lost wages due to sickness. Their success and wealth caused corporations to muscle into the territory, pushing for laws to limit the right of fraternals to insure.

Concerned citizens in North Carolina rally for health care reform. Photo credit: TW Buckner. Used under Creative Commons license.

So, today, most insurance law is written by and for insurance companies. Whereas a grassroots co-op grows incrementally, most insurance regulations mandate comprehensive coverage that requires high premiums to support large staff. Thus, price of entry into the poker game is high.

When starting a Philadelphia health co-op, I was blocked by the Pennsylvania Insurance Department. In response, I wrote the book A Crime Not a Crisis, detailing collusion between state legislators, regulators, and insurers to keep profits high. Since then, I’ve launched the League of Uninsured Voters (LUV) to rally Americans to kick insurers aside, while building a health system devoted to people. Even were Medicare extended to everyone someday, Americans will need to be organized to fight to keep it.

By contrast, the grassroots co-ops, based on generosity, will create a national nonprofit infrastructure that’s essential for a national health plan that’s affordable, democratic, and humane.

Most recently, I’ve been organizing to build the first Patch Adams free clinic, a passive solar earthship surrounded by greenhouses and orchards on a large vacant lot in a low-income neighborhood. We’ll serve one another in the spirit of love, justice, and fun.

Here are the basic elements:

- Make a simple plan affordable by all: $100, $200, or $300 per year.

- Incorporate as a tax-exempt organization: 501(c)15 or as a co-op.

- Find pioneer members.

- Put money into a tax-exempt bank account.

- Find pioneer healers for discounts.

- When $10,000, start a broken bone fund, maximum 5 percent of total in fund.

- When $20,000, set a maximum for broken bones and add emergency stitches.

- When $30,000, add first and second degree burns.

And so forth. Your member-owned free clinic can be started inexpensively. To enable other communities to start their own health co-ops, I wrote the book Health Democracy which explains, step-by-step, how we successfuly expanded categories and payment maximums.

The first page of H.R. 3200, also known as the Affordable Care Act or Obamacare. Photo credit: Listener42. Used under Creative Commons license.

When corporate laws become a cage for us to die in, it’s time to break the lock. Here are guidelines for model legislation:

1) Charge a maximum $300 per person per year (adjustable annually for inflation). Our intent has always been to make co-op membership accessible to the lowest-income residents. We have sought to prove that small amounts of money, multiplied by large numbers of people, can fund nonprofit systems that serve better than for-profit systems. Our small health plan has already enabled people to buy lower-cost, higher-deductible standard coverage. Yet, since even $100 per year is more money than many can afford, we invite donations to a fund which donates memberships.

2) Pay claims without requiring a deductible. Community ownership of a health system means more than just paying medical bills; it means funding free clinics, providing preventive care and/or health education, advocating for healthier cities, and so on.

3) Pay claims billed by any credentialed health provider anywhere. Because we pay only for specified non-elective care (emergencies), we do not need to leverage provider discounts and can afford to pay any doctor. We are not a preferred provider network.

4) Enroll members without collecting information about gender, age, ethnicity, income, or personal/family medical history. Such information enables insurers to discriminate against people likelier to need their services

5) Permit members to vote for board of directors annually and to initiate referenda. Essential to the democratic process, voting allows members to restrain their governing body.

6) Require that board members reside within the county where the organization is incorporated or within counties adjacent. Local boards are potentially more accountable because board members must preserve their community standing. Alliance members can lobby board members on the street.

7) Require that all board meetings take place in the county where incorporated. This makes access easier for the majority of members. Several general members who have attended board meetings have become candidates for the board.

8) Pay administrative employees not more than twice the state’s livable wage, regionally adjusted. Staff-driven organizations divert money from the original mission to ever-expanding salaries and benefits. Alliances are operated by people motivated by generosity rather than greed — people who are more keen to accumulate gratitude than consumer goods.

9) Do not hire commission agents. Selling memberships on commission encourages shortcuts that undercut service and honesty.

10) Maintain a website which presents bylaws; covered categories and maximum amounts paid; current balance sheet (including general fund total, income and expenses by category/month/year, detailed expense sheet, list of each payment and each denial of payment by member number); time and place of next board meeting; minutes of board meetings; statements by board candidates. The Internet has become an essential tool for communicating with members, for bringing in new members, and for keeping the organization honest and accountable. No other health plan lists its payments and denials of payment.

11) Maintain a listserve for members which facilitates publication of monthly reports and electronic voting. As above, e-mail enables two-way communication with greatest ease and least cost.

12) Enroll at least 51 percent of members from the county where incorporated and adjacent counties. This retains maximum democratic control by enabling more members to attend meetings and serve on committees.

13) Publish conspicuously and in bold-face type not smaller than 10-point type, on the first page of any literature, that "This organization does not operate under the supervision of the [State] Insurance Department. This is required in NYS for compliance with section 4522.

14) Publish quarterly reports to the state’s insurance department, detailing compliance with the above. We prefer that a state’s insurance department look over the shoulder of the co-op sector to assist in the credentialing of health alliances.

15) Publish atop the list of covered categories, in bold-face type not smaller than 14-point type, that “This Fund is not a major medical plan. It covers only the categories listed below, to the maximum amounts specified.” We do not encourage people to drop their major medical coverage if they can afford to keep it. Members should be reminded that, as the co-op is small, they may need help beyond our capacity.

16) Comply with HIPAA regulations. Whether required to protect privacy or not, we prefer to do so. Privacy is so important that we feel the federal government itself should not have access to member records. Members are to be notified when government copies their records.

Paul Glover is the founder of 18 organizations and campaigns, including HOURS, Philadelphia Orchard Project, Citizen Planners of Los Angeles and League of Uninsured Voters. He’s author of six books and a former professor of urban studies at Temple University.