To coincide with Shareable's Share or Die Storytelling Contest, and the print release of Share or Die, we present this excerpt from Winning the Story Wars, the new book by Free Range Studios Co-founder and Storytelling Contest judge Jonah Sachs. In the book, Sachs argues that society lacks stories offering meaning, and tracks the rise of the marketer as mythmaker.

June 16, 1945, 4:00 a.m. For weeks, he had been living off of hand-rolled cigarettes and ancient Sanskrit poetry. Starved, parched, six feet tall, and 116 pounds, there was almost nothing left—a wasted man in a wasteland.

He ran his fingers over the dusty earth; his back turned to the hastily constructed city of several thousand. Most of them were sleeping as if it was just another night at summer camp. He liked that camp feel. It discouraged the asking of too many questions. It softened the anxious curiosity of the wives and children, preserving the secrets that were everywhere.

This year, we’ve seen Mutual Aid in Motion.

From scaling sharing hubs to Mutual Aid 101 trainings, we’re helping communities build the tools they need.

Every dollar fuels lasting resilience – proving that when we move together, we all move forward.

A jeep rolled by, headed for the test site, and he waited for another flash of lightning. When it came, he could, for an instant, make out the vast New Mexico nothingness that had, even as a young man on summer vacation, made him feel at home.

“Like a nuclear bomb was dropped here,” he thought, playing with the words for the first time.

It would soon come to be a horrifying cliché, used to describe anything from a flood-ravaged town to a child’s unkempt room, the expression of an ever-present, crushing fear shared by billions. But the words passed through Oppenheimer’s mind first. On that particular day, only he and a handful of other exhausted men even knew the bomb existed.

That the “gadget,” as they affectionately called it, would work was far from certain. The men had put together a pool to predict the power of the nuclear implosion they were hoping to create and guesses ranged from nothing at all to only-half joking predictions that the entire state of New Mexico would combust. Oppenheimer, the man responsible for the project’s success, had played it safe in front of his men, gloomily predicting a blast equivalent to a mere three hundred tons of TNT. In the language of bombs, three hundred tons was hardly a game changer.

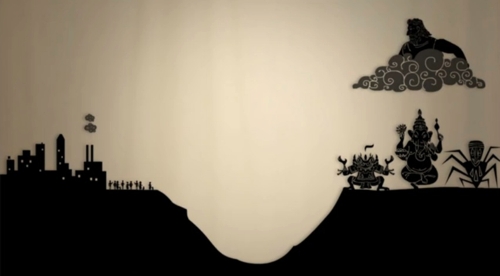

But in his private moments, Oppenheimer was feeling far less humble. He had been reading the Bhagavad Gita, one of the great foundational Hindu scriptures, in nearly every spare moment. Each time his thoughts wandered to the awesome power he was about to unleash, he brought them back to the story contained in the two-thousand-year-old sacred text. It was science that he used to design the bomb. It was a myth that he relied on to understand its significance and his place in the epoch-making moment about to unfold.

At times, he thought he must be living out the story of Arjuna, the reluctant hero-warrior, forced into battle against his conniving cousins. In the Gita, Arjuna appeals to Lord Krishna for help and is offered the benefit of either Krishna’s vast armies or his bottomless wisdom. He chooses the power of the mind over the power of the physical world. Arjuna’s story fit Oppenheimer’s own nicely. That the wisdom of a few men could overcome the armaments of thousands, even millions, was what he had been hired by the army to prove.

Then again, he suspected that the bomb was more significant even than that. Perhaps his story was not that of Arjuna, the warrior, but of Lord Krishna, himself an incarnation of the Supreme Being. After all, until this moment, it had been only the gods who held the power to utterly destroy worlds. It had now become likely that that power would fall into the hands of man—and largely because of him.

The lightning had stopped, and he lit another cigarette with the glowing end of his last one.

“Krishna,” he thought. “Why not?”

A jeep pulled up a few yards away, his brother Frank already in the passenger seat. Without a word, Oppenheimer stepped inside.

5:29 a.m. “Now!” the announcer shouted and the men in the bunker braced themselves—terrified that it wouldn’t work, terrified that it would. Ten miles away, there was a flash and suddenly the predawn became day—the brightest and hottest any of them had ever known. A plume of flame raced skyward, seven miles high, and ballooned out at the top, glowing with an eerie light of purple and green. Forty-five seconds later, the blast reached the men, disturbing the otherwise perfectly still air. Thunder echoed and bounced across the desert, eerily repeating itself in a wholly unnatural way. There was jubilation for several moments. But as the men slapped backs and called each other “sons of bitches,” Oppenheimer’s mind returned to the Gita. He would later vividly recall his thought of that moment—the thought of a man challenging the supremacy of the gods.

“I am become death, the destroyer of worlds.” His words were the words of Krishna revealing his divine form.

But all he said aloud was: “It worked.”

With a blast equivalent of 18,600 tons of TNT, indeed it had.

Four hours later, another “gadget” known as Little Boy left Hunter’s Point in San Francisco. In three weeks, two bustling Japanese cities would be as wasted as the New Mexico desert.

Oppenheimer and his men had seized the power of the gods for humankind and they knew it, just as the rest of the world soon would. This bomb dealt a fracturing blow to a pillar of the cultural mythology the world had been living by for millennia. In the West, our shared traditional stories are largely drawn from the Old Testament, itself drawn from far more ancient sources. These myths cast man as a humble and small being subject to the whims of the much larger power of God and nature. At least since the time of Galileo, science had begun to offer alternative explanations for the forces around us, but until that blast went off, science’s enormous power had never been so undeniably manifested in the real world. No wonder Oppenheimer found himself in such a mythic state of mind leading up to the blast. No wonder he would later compare his team to Prometheus, stealing fire from the gods.

In the words of Isidor Rabi, who held the winning wager in Oppenheimer’s pool: “A new thing had just been born; a new control; a new understanding of man, which man had acquired over nature.” And Albert Einstein urgently warned: “The unleashed power of the atom has changed everything save our modes of thinking and we thus drift toward unparalleled catastrophe.”

What Rabi and Einstein recognized is that changing times were deeply challenging our old ways of seeing and responding to our world. It’s not technology that can save us, Einstein would repeatedly emphasize; it’s a new mind-set. And the mind-set of a society is held in its shared myths. The myths of our ancestors were just not equipped to handle the bomb Einstein had helped Oppenheimer create.

How we choose to update those myths, our most important cultural stories, and how we choose to enact them, will in large part determine society’s response to our rapidly changing times. Through the lens of the story wars, we’re about to see that marketers now have a major part to play in this choice.

The detonation in the New Mexico desert—now a lifetime ago—marked a major lurch in the widening of our myth gap—the space between the realities of our moment in history and the shared stories to which we turn for explanation, meaning, and instruction for action.

It is this myth gap that we’ll now explore—the rift marketers have stepped into where religion, science, and entertainment have faltered.

What Is a Myth?

It is both tragic and deeply ironic that our society commonly relegates the word myth to a reviled synonym for a lie. Today, when we speak of myths, we’re more likely to think of busting them than looking to them for guidance. Yet to live without myths would put us in uncharted territory in the history of human civilization.

Myths are the glue that holds society together, providing an indispensible, meaning-making function. British anthropologist Bronislaw Malinowski said myth “expresses, enhances and codifies belief, it safeguards and enforces morality, it vouches for the efficacy of ritual and contains practical rules for the guidance of man.” What we value and what we do not are codified and shared in our myths and this makes them enormously powerful—and necessary.

When myths are functioning properly, they bring us together and get us to act by using a specific formula that appears to be universal across all cultures.

Myth Ingredient 1: Symbolic Thinking

Myths are neither true nor untrue, because they exist in a separate space and time. They need not conform to the literal constraints of reality. In fact, most societies have set the scene for their myths in a separate reality altogether—either long ago or far away. This sacred, imaginative realm informs the literal world but exists apart from it.

Using a symbolical language, myths allow us to break free from the often befuddling stream of facts that reality sends our way. They allow us to see the world through powerful symbols that stand in for and remind us of deep truths—truths that are often hard to grasp in literal language but easily evoked in symbols. You can think of the mythic realm like the realm of your dreams—not exactly real but deeply relevant to explaining reality and guiding life. In fact, Joseph Campbell called myths “public dreams.”

Existing in the symbolic world makes myths flexible. New experiences of reality, even an earth-shattering invention like the atomic bomb, don’t necessarily disprove them. The Bhagavad Gita has provided deep meaning on the proper way to live life for millions of people, including Robert Oppenheimer. It does not demand, however, that you believe the battle between Arjuna and his cousins really existed. Hindus can openly debate the symbolism of this story without fearing the charge of heresy. For most of human history, myths have survived through changing times because they did not demand to be seen as a literal retelling of events.

Myth Ingredient 2: Story, Explanation, and Meaning

Myths provide story, explanation, and meaning in a single neat package. Take one of our most powerful myths, from which so much of our cultural history has derived—the first book of Genesis:

STORY: God created the world in seven days and gave man dominion over it.

EXPLANATION: This is how everything we see around us came into existence.

MEANING: So God deserves our gratitude and obedience.

The same elements can be found in modern foundational myths too, like the myth of the American dream.

STORY: America was clawed from the tyranny of British class and privilege and formed into an exceptional nation by men who believed in liberty, merit, and self-discipline.

EXPLANATION: That’s why opportunity for success and prosperity is open to every American.

MEANING: So if you work hard, you too will be rewarded.

Any myth can be broken down this way. There is no right or wrong way to interpret a given myth. But if it is a myth and not simply a tale told for amusement, you should be able to find story, explanation, and meaning packaged within.

Myth Ingredient 3: Ritual

Stories that provide compelling explanation and meaning can’t help but hit us with a powerful moral of the story. And the first thing we do when hear a good moral is to wonder how we can apply it to our own lives. What believer of Genesis will not wonder: “What do I have to do to serve God?”

Because myths are set in a realm apart, humans have always sought to enact them in the real world through rituals. Rituals from a Passover Seder to a family ceremonially gathering to sign a first mortgage are how human beings make myths real.

When these elements are brought together—symbolic thinking, story, explanation, meaning, and ritual—the building blocks are in place. But not all stories of this kind actually become myths that shape society. For that to happen, these stories must be accepted by enough minds to approach a universal reference point. As we’ll see, the myth gap has all but destroyed the universality of our myths.

The Opening of the Myth Gap

Myths tend to be extremely resilient, often persisting and evolving for millennia. But a myth gap arises when reality changes dramatically and our myths are not resilient enough to continue working in the face of that change.

Change has been accelerating at an ever-increasing pace over the last hundred years, and Oppenheimer’s bomb caused only one tectonic shift in global consciousness. In the United States alone, we might also point to the civil rights movement, the Vietnam War, Watergate, the discovery of the ecological crisis, and the 2008 global financial collapse. It would have taken some extremely flexible mythology to continue to provide universal guidance in the face of all of these shifts.

As it turns out, our religious myths have not, for many, proven to be nearly flexible enough. And while we might have turned to science and entertainment to provide alternatives, these realms also have not been able to fill the gap with new myths. This has left the door wide open for marketers, who have gladly stepped in. But before we explore that history, I’ll take a moment to explain what the modern myth gap looks like.

The Gap of Symbolic Thinking

Our mythic landscape has become brittle because many people have rejected the notion of thinking symbolically—and that’s unique to our rationalist modern society. Today, we demand to know if something is true or not. This is why science and religion compete so furiously. Either the world is six thousand years old or several billion. Either we are descended from apelike ancestors or created by God. To the modern mind, only one can be right, and the other is wrong. To the mythological mind, both can easily be true. Held to the standard of literal truth, traditional myths start to crack.

The Gap of Story, Explanation, and Meaning

Today in our extremely diverse society, we perceive the functions of story, explanation, and meaning as dispersed among the realms of religion, science, and entertainment. When it comes to closing the myth gap, no one of these is stepping up to provide the complete myth packages we need.

Here’s why: religions continue to play a powerful role in providing explanation and meaning, but please don’t call the teachings contained in their holy texts stories. Today’s mainstream religious leaders fear nothing more than the perception that their teachings sink to the level of myth. Mainstream religious communities ask that their religious stories be believed literally—and that price of entry proves too high for many. Religious myths are far from dead, but this rigidity causes them to drift further and further from universality.

Science, too, which now offers a powerful alternative to religion in terms of explanation, has shied away from the discussion of meaning. And, mainstream science, like religion, chooses not to present itself as a collection of stories at all.

Movies and television dominate our vibrant realm of imaginative storytelling, and most carry only a single burden—the expectation to entertain. Some entertainment is so popular as to achieve the status of universal cultural reference point. But few of our entertainers accept the responsibility of providing audiences with a genuine explanation of how the world works or offering deep meaning.

While pockets of forward-thinking religious leaders, scientists, and entertainers have attempted to reunify story, explanation, and meaning in their work, they all remain firmly out of the mainstream. And for a myth to function in society, it can’t exist on the fringe. Where ancient and traditional society could turn to shamans and sages who took pride in combining story, explanation, and meaning, these sources have now disappeared or lost their widespread legitimacy.

The Gap of Ritual

Today’s religious rituals are far too diverse and conflicting to provide our society any kind of universal glue, and they have had trouble evolving fast enough to meet changing realities. Entertainment isn’t much help, since it emphasizes passive viewing, not active engagement, while science rejects the magic of symbolic action altogether.

With gaps like these opening up everywhere in the twentieth century, we need a new generation of effective storytellers—those to whom we can turn to update fraying myths and rituals and, when necessary, introduce new ones. As Robert Oppenheimer helped catapult us into the anxious age of the myth gap, we looked to our traditional mythmakers. They were unable to deliver the updated myths we so desperately needed.

The Marketer Becomes the Mythmaker

Of course, the opening of these gaps has been profoundly uncomfortable. Psychologist Carl Jung signaled an early warning about the myth gap just before the outbreak of World War I. Myth, he said, “is what is believed always, everywhere by everybody; hence the man who thinks he can live without myth or outside it, is an exception. He is like one uprooted, having no true link with either the past, or the ancestral life within him, or yet with contemporary society.” In other words, societies without myth might easily fall apart. And a world full of such mythless men is a dangerous place.

Not long after Jung began to fret about men without myths, industrialists came face to face with an existential crisis of their own. World War I had mobilized the American economy to produce a tremendous quantity of material goods. Once the machine got rolling, it was no simple matter to turn it off, even once the war ended. The job and stock markets of an urbanizing America absolutely depended on continued production, or economic freefalls would ensue. But production of what? There was simply not enough demand to meet the supply. The myth gap was matched by an equally disturbing demand gap.

Thus the opportunity for a new kind of mythmaker—the marketer—presented itself. In fact, American political leaders of the time practically begged marketers to step in. As a result, the marketer went from a product pitchman to a major player in our cultural destiny.

Let’s go back for a moment to early part of the twentieth century: Puritan values and rituals, derived straight from the book of Genesis, had built an America whose story, explanation, and meaning was based on thrift and modesty. (That history is illustrated, for example, by Benjamin Franklin’s simple and wildly popular aphorisms, which had taught a nation to work hard and save heartily.)

To fill the demand gap, society itself would have to be revolutionized—transformed into something entirely new. Here’s a perfect example of a myth challenged by vastly changed circumstances that had to be either updated or replaced. Just as Einstein called for a new mind-set to avert nuclear disaster, leaders twenty years earlier were calling for a new mind-set to avert an economic one.

During World War I, the marketing industry had flexed its muscles for America’s leaders by turning the majority of its attention to the war effort, and it had delivered powerful results. As the new threat of soft demand emerged, our leaders again turned to marketers and in clear terms asked them to do what religion, science, and entertainment had failed to do: activate new myths to keep the economy going.

Listen to Calvin Coolidge addressing a gathering of top advertisers: “[Advertising] is the most potent influence in adapting and changing the habits and modes of life, affecting what we eat, what we wear and the work and play of the whole nation. Advertising ministers to the spiritual side of the trade.” And Herbert Hoover: “You have taken over the job of creating desire and have transformed people into constantly moving happiness machines— machines which have become the key to economic progress.” Coolidge and Hoover, the top political leaders of their day, were inviting marketers in no uncertain terms to create new explanations of how to live, new meaning and new rituals. In other words, marketers were being asked to step into role of modern mythmakers.

Marketers, of course, were uniquely suited to accept that role because they had the tools to close all the gaps that religion, science, and entertainment had left open. Since the late 1800s, the marketing industry had known about the power of telling stories in their advertisements. By the turn of the twentieth century, story-based campaigns like “Spotless Town” had rocketed Sapolio soap out of bland commodity status and into a highly coveted product. The poem-based stories of a fictional town built around the brand had become a regular dinner-table discussion topic in American homes. Stories like these were all about thinking symbolically. Nobody thought that Spotless Town, the Jolly Green Giant, the Morton Umbrella Girl, or the Marlboro Man were real, but they were still seen as powerfully instructive in the real world. Tens of millions of American smokers would switch brands in order to emulate the rugged role model they knew was fictional. This is the power of symbolic thinking that drives myths. Denied it elsewhere, people flock to these symbolic stories when they are put on offer in the marketplace.

The stories marketers tell have always done the work of myth in providing explanation and meaning. Every new product launch, from liquid dish soap to the iPad, has been a new practical explanation of how to live an ever-changing modern life. These explanations update as fast as the circumstances of our lives do, sometimes even faster. And from its most primitive days on, marketing has been about allowing a product or service to confer meaning on the purchaser. Even our take-out coffee container is a signifier of meaning and belonging. Looking at the cup, we know what tribe we are part of—Starbucks paper cup? Mainstream good lifers or aspiring to it. Dunkin’s Styrofoam? Downscale and proud. Reusable steel travel cup? Eco-conscious and responsible.

And ritual? Well, of course. What’s the good of a marketing story if it doesn’t give audiences a way to live that story out? You might say that introducing a new ritual is the basis of every marketing campaign. Shopping has become the single ritual we universally share.

Symbolic thinking. Story, explanation, meaning, and ritual. Marketers would get the myth formula down cold. And thanks to a masterful class of marketers, the demand gap was decisively overcome as America shifted into hyperconsumption mode. The Puritan values of thrift and modesty were smashed, abandoned for easy consumer credit, conspicuous consumption, and deep personal relationships with brands. In terms of epoch-marking changes, this has been as profound a shift as the atom bomb.

The marketers who emerged as the new masters of the story wars had the complete package, ready for universal application. Cheered on by the highest powers, they began to update old myths and imagine new ones. History provides plenty of close-up looks at exactly how it’s been done.

Cigarettes and the Myth of Adam’s Rib: “Torches of Freedom”

Unto the woman he said, I will greatly multiply thy sorrow and thy conception; in sorrow thou shalt bring forth children; and thy desire shall be to thy husband, and he shall rule over thee.

— Genesis 3:16

By the beginning of the twentieth century, America’s traditional agrarian life was being challenged by a new dominant force—the modern city.

Compared with life in the growing metropolises, life on the farm was only a stone’s throw from the spot outside of Eden where Adam and Eve made their homestead after that little misstep in the garden. The scenario included a father who toiled on the land, ruling over his small dominion, and his wife as his helpmate. To a society based on this way of living, Genesis 3:16 provided reasonable story, explanation, and meaning. Everyone was familiar with it and almost everyone was living it.

But as women found independence from the old order and gained access to the educational and work opportunities that cities offered, “thy desire shall be to thy husband” was no longer a necessity for survival. In fact, to some of these women, it had stopped making sense at all. One culture-rocking outcome of this emerging rejection of Genesis 3:16 was the notion that women should have the right to vote. The idea that Eve might not agree with Adam on matters of public life was an 18-kiloton assault on a myth that had gone largely unchallenged for almost two millennia.

By the turn of the twentieth century, a new myth—that of the American woman on equal footing with the American man—was struggling to take root in the popular imagination. A small but influential group of urban suffragettes had begun marching in the streets, demanding the vote and sparking a major debate across the nation. These few women were prying open the myth gap, but it was a marketer, Edward Bernays, who would fill that gap by giving every American woman a ritual by which to live the suffragette’s story—not by joining the marchers, but by smoking.

Bernays, Sigmund Freud’s nephew, was the inventor of the field of public relations, a phrase he coined himself. Unlike other marketers of his day, Bernays saw marketing not as an exercise in providing products people desired. Instead, he claimed to be able to create new desires using his uncle’s fresh insights into psychology.

In 1928, George Washington Hill, the president of the American Tobacco Company, approached Bernays with a problem—the old stories about American womanhood were encouraging women to be far too modest. These stories were the source of serious taboos against women smoking in public. Only a few years before, a woman in New York had been arrested for lighting up on the street. Just like voting, public smoking was a privilege of men, and that was bad for business. Bernays had a solution.

If the smoking ritual Hill was trying to sell wouldn’t work with the old myth, why not attach it to a new story with tremendous momentum? Only eight years earlier, the 19th Amendment had been ratified, giving the suffragettes a monumental victory. Of course, they had no intention of stopping with the vote; the push for equality had only just begun. Perhaps providing the new story these women were writing with a ritual—smoking—could elevate their story to the level of myth. And more than a few cigarettes would be sold along the way.

The idea first occurred to Bernays after he brought a cigarette to a top Freudian analyst. “The cigarette,” the analyst told him, “is a symbol of the penis.”

“Well,” Bernays reasoned. “If women are wanting everything men have, what could be more primal than wanting a penis?” With penis envy on the brain, Bernays scribbled out a strategy to get women smoking by tying the cigarette to an emerging story that turned Genesis on its head. Women who wanted everything men had would be taught to want cigarettes, too.

Bernays hired a bunch of glamorous young women to march in the New York Easter Day parade posing as suffragettes. At a given signal they were to reach under their skirts, pull out cigarettes and light up, calling them “Torches of Freedom.” The phrase stirred Bernays’s soul as soon as he penned it.

He tipped the press off ahead of time about the planned rebellion. The stunt went off without a hitch, and it rocked the American imagination. Papers across the nation ran stories about these “suffragettes,” and advertisements to drive the point home quickly followed. The taboo against women smoking in public came crashing down. Within a decade, there would be dozens of national brands designed and marketed specifically for women.

It was the suffragettes who helped to open the myth gap, putting a face on this renegotiation of Old Testament values. They became major characters in the powerful new mythology of American womanhood that continues to transform society to this day. And it was a marketer, Edward Bernays, who helped to activate this emerging mythology so it could be universally shared and lived by all American women. It would powerfully and conveniently connect millions of women to a new story, explanation, and meaning every time they went through the ritual of lighting up.

Litter and the Myth of the Wild Frontier: The Crying Indian

And God blessed them, and God said unto them, Be fruitful, and multiply, and replenish the earth, and subdue it: and have dominion over the fish of the sea, and over the fowl of the air, and over every living thing that moveth upon the earth.

—Genesis 1:28

Just as the Genesis story teaches a man to rule over his wife, it’s also pretty clear about how mankind should deal with the Earth: Subdue it. As soon as our Pilgrim forefathers first beheld the marvelous expanse of seemingly uninhabited forests that would be their new home, Genesis 1:28 was instantly reactivated. To people coming from a crowded, deforested European continent, this was like a return to the Garden and a chance to carry out God’s commandment anew. The idea of a virgin wilderness awaiting human hands has been at the heart of American mythology ever since.

So, from the beginning, American heroes have been pioneers, hunters, and cowboys—Davy Crockett, Johnny Appleseed, Annie Oakley, John Wayne, Rambo—men and women willing to step out of the safety of civilization and onto the frontier, clearing the next patch of ground for the use of civilized people. Our stories from Westerns to space epics take place on the frontier because that’s where our core Genesis-based mythology can be lived out.

In the language of the frontier myth, leaving nature unexploited by human hands is not just a waste; it is an act of immorality, a rebellion against God’s commandments. Thus the myth of the frontier became a powerful guide for action in two ways: It instructed Americans to continually push the frontier outward, exploiting land not just for economic gain but for spiritual redemption. And it justified the removal of “immoral” native people who were brazenly failing to subdue the land they inhabited.

Into the 1960s, this two-part frontier myth held enormous, near-universal cultural resonance. Intact, it made for powerful story wars marketing fodder. When Leo Burnett took over the Marlboro account, filtered cigarettes were seen as a lady’s product (Bernays must have been proud). By introducing the rugged Marlboro Man, Burnett gave the frontier myth a new symbol and a universal ritual through which any male could assert his cowboy masculinity. The Marlboro Man singlehandedly made his cigarette the best-selling brand among male smokers for generations. Most Marlboro ads consisted of nothing but a single image and the brand name. The myth did all the heavy lifting. The Marlboro Man is still regarded as the most iconic brand spokesman in advertising history—and he never uttered a word.

Around the same time the Marlboro Man was born, the Kennedy administration was leveraging the “savage” part of the frontier myth to justify engagement in the emerging conflict in Vietnam. As American myth expert Richard Slotkin points out, John F. Kennedy’s ambassador to South Vietnam, Maxwell Taylor, described and justified military actions as moving the “Indians” away from the “fort” so that the “settlers” could plant “corn.” Soldiers responded deeply to the mythic lingo, for years, they would commonly describe Vietnam as “Indian country” and search and destroy missions as a game of “cowboys and Indians.” Even once the literal American frontier had been closed, its mythological resonance was alive and well, endlessly providing story, explanation, and meaning. Everything from smoking to war could be seen as a ritual enactment of it. And then things began to go terribly wrong.

In 1962, Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring hit the New York Times best-seller list and launched modern environmentalism. The book focused on DDT—the ultimate Earth-subduing pesticide that had made it safe to “plant corn” in the wilderness. The book sensationally revealed the chemical’s unintended and devastating ecological side effects. We were suddenly confronted with an all out story wars attack on the biblical exhortation to subdue nature. Many awoke for the first time to the possibility that in beating back nature, we were beating back ourselves. Perhaps it wasn’t man versus nature after all. Perhaps it was man and nature versus oblivion. We had once been at the mercy of God and the natural world, frightening and powerful forces. Just as Oppenheimer’s bomb made us realize that we humans might be as powerful as God, Silent Spring was the first step in the realization that nature might be at our mercy.

The myth gap grew and eco-anxiety began to pervade the American public, growing more intense with each successive revelation: ozone depletion, species loss, and, of course, climate change. The man versus nature myth, once so universally shared, began to divide society. Environmentalists have been toiling ever since to update and rewrite the myth. Those who oppose the “treehuggers” seem to cling to the myth ever more fiercely, rejecting any scientific evidence that might question the march of economic growth.

As our relationship to nature on the frontier began to crack, so did our relationship to its “Indians.” The situation was deteriorating in Vietnam. Opposition to the war was rising steadily, and for the first time, the myth of America as an archetypal cowboy battling for good on the frontier was being loudly and widely questioned. This new thinking combined with the dawning realization brought to us by the civil rights movement that, long after the abolition of slavery, America did not always fall on the side of justice and freedom. The myth of the virtuous settler versus the immoral savage began, to many, to seem a relic of a disappearing age. Even Western films began to question past treatment of Native Americans; eventually the genre would shift 180 degrees, to the point where films like Dances with Wolves and Avatar, in which the natives are the centers of virtue, would become the norm. Instead of subduing the Indians, the cowboys of these new stories would learn from them and adopt their ways, becoming completed heroes in the process.

By the 1970s, with both core pillars of the frontier myth—the subjugation of nature and the savagery of Indians—deeply embattled in the story wars, there was a clear need for access to an updated version of the myth. The marketing masters behind the Keep America Beautiful campaign saw a chance to provide just that.

Despite its public service-y name, the campaign was largely a food industry attack on laws that would limit packaging waste or add deposits to disposable bottles. The campaign set out to undermine these efforts by firmly implanting the idea that litter prevention was a personal, not an industry, responsibility. The “Litterbug” campaign placed the blame for our garbage-strewn cities and highways not on wasteful packaging but on immoral individuals. Its tagline: “People start pollution, people can stop it.” The statement, of course, hides the fact that for every can of trash that people throw away, seventy cans of trash are made upstream.

In 1971, with a flood of troubling ecological revelations pouring in and the war in Vietnam worsening dramatically, Keep America Beautiful provided the perfect therapeutic response to the anxiety caused by the crumbling of our cherished frontier myth. Its marketers would call their story-ad the Crying Indian, and it is considered the most iconic, and possibly effective, PSA of all time—and a powerful example of story wars mastery.

The ad stars actor Iron Eyes Cody (actually, an Italian immigrant who made a career of portraying Native Americans). As the ad opens, Cody rows his canoe majestically, tense music rising. The camera pans up to reveal that he is on a bleak, modern industrial river—he is on subdued land and it is anything but virtuous. Within ten seconds, the myth gap is invoked. But can the marketers close it?

Cody pulls the canoe onto a littered beach and the announcer’s voice warns: “Some people have a deep abiding respect for the natural beauty that was once this country. And some people don’t.” A car drives by and some jerk tosses a plastic bag out the window. We zoom into the Indian’s face and a single tear rolls down his cheek. America, from all sides of the political spectrum, burst into tears with him.

But wait—here comes the tagline and something we can do to be part of this new story—a story in which nature is respected, our former beauty restored. It’s a story in which the Indian is the hero, the cowboy in the car the villain: “People start pollution. People can stop it.”

The Ad Council marketers working for Keep America Beautiful, like Edward Bernays before them, offered a symbolic ritual that was available to all. Litter prevention and eventually recycling would become healing acts by which people could overcome the anxiety of a broken myth and feel virtuous again—reconciled with their planet and with their past.

Tea, Tents, and the American Dream: Responses to Economic Crisis

Each man and each woman shall be able to attain to the fullest stature of which they are innately capable, and be recognized by others for what they are, regardless of the fortuitous circumstances of birth or position. —James Truslow Adams, who coined the term the American dream

Of course, the anxiety created by myth gaps and the power conferred to those communicators who heal them continue to fuel the story wars to this day. As I write, the most salient emotion on both sides of the American political spectrum is anger. And that anger has been the direct result of the fraying of perhaps our greatest national myth.

The American dream equates liberty with economic opportunity for anyone willing to work hard, and it stands at the heart of the concept of America as an exceptional nation. But the 2008 economic meltdown and the government bailout of the “too big to fail” financial institutions seemed to many to be laser-targeted at dismantling the promises of the American dream. Jobs, pensions, and home ownership—the average citizen’s just rewards for hard work—had evaporated. This cherished story suddenly appeared to be a lie.

Two movements focused that anger with sensational effect, driving thousands of Americans to the streets and dominating the media: the Tea Party and Occupy Wall Street. Where countless top- down efforts failed to capture the imagination of a seething public, these two movements caught on. Characteristic of the digitoral era, they may not look like marketing campaigns, but they are. Both were intentionally sparked by nontraditional media outlets whose aim was to create a brand that would focus political rage.

The emotional impact of these movements in the United States came from the fact that they offered a modernization of the myth of the American dream that fills an unbearable gap.

Their policy platforms, if they can even be defined, were hardly new or distinct. It was their symbolic imagery that is breakthrough—modern-day American revolutionaries and “the 99 percent.”

The Tea Party invoked the genesis of the dream—when our founding fathers declared emphatically that this land does not belong in the hands of ruling elites. Their declaration of liberty, expressed in economic terms—the Boston Tea Party was, after all, an act of resistance to taxes—is the foundation of the dream. As recession began to unravel the dream, the modern-day Tea Party sought to inspire Americans to believe that the downturn’s attack on their prosperity was actually an attack on their liberty. By wearing eighteenth- century garb and squarely pointing their near-violent fervor at a government too big and too out of touch, they turned the complexities of the financial collapse into a simple and familiar morality tale, reconnecting it to a story everyone was familiar with. By naming the dismantler of the dream, the party responsible for the myth gap, they identified a clear villain (the government) and a clear conflict (resistance). Suddenly, the collapse was no longer a force of nature but a battle.

Hundreds of thousands signed up to fight this battle and reaffirm the myth. Still flush with victory in 2010, Americans for Prosperity, a DC advocacy group, which had been a key organizing force in the movement, held a national training event for Tea Party leaders. They called it “Defending the American Dream.”

Occupy Wall Street may have had very different policy aims, but its breakthrough message of “the 99%” also worked to reaffirm the values of the dream and to provide clear character and conflict. It’s worth noting that the message of Occupy differed from the Tea Party in that it did not seek to reaffirm American exceptionalism— it saw itself as an inclusive global movement. Otherwise it filled the myth gap in very much the same way. “The 99 percent” resonated as shorthand for the American dream concept that economic prosperity should be available to anyone willing to work for it. It must not be the exclusive provenance of the powerful elite. Like the Tea Party, the 99 percent message focused public anger by identifying a villain and inviting its followers into conflict. Instead of an overactive government, the elitist villains of the Occupy myth are corporations (embodied in the symbol of Wall Street) and a government weakly following their commands.

Even as the physical Occupations began to slow, it was clear that the battleground was not the parks but the story about what America is. That’s why Republican messaging guru Frank Luntz said: “I’m so scared of this anti–Wall Street effort. I’m frightened to death. They’re having an impact on what the American people think of capitalism.” While most media outlets focus on the fight in the streets, Luntz clearly sees the more important fight for the myth.

Both of these movements worked because they stepped into the gap left behind by the fraying myth of the American dream to supply new story (they provide clear character and conflict), explanation (they tell us that the root cause of the complex meltdown is simple), meaning (the exhort us as average people to stand up), and even ritual (they invite us to tea parties and tent cities). Their therapeutic and viral power was not contained in their manifestos but in the new myths they provided.

Success in the story wars began for all of these campaigns— from Torches of Freedom to today’s explosive political movements— in understanding the state of the myth gap at the moment of their release. Every marketer is looking to tap into the zeitgeist, and there is no more direct way into it than through the void created by fraying myths. This is where anxiety is welling up. This is where people are looking for therapeutic relief. This is where new ritual is ripe for the making.

Marketers as mythmakers. Is this something to be excited about? Terrified of? Though some may instinctively wish to return to a media landscape ruled by shamans, bards, or priests, that’s not likely to happen any time soon. That marketers are some of our most powerful mythmakers is, for now, a basic fact of life. And marketers would be foolish not to take advantage of the power this confers—it’s the most direct path to success in the work we do. In fact, this book is a call to fully embrace that mythmaker’s role and join the story wars. But if we do, we must also accept the responsibility the role carries. As thinkers from Jung to Einstein to Coolidge make clear, these stories are not idle play. They can set the direction of a society’s future. And as we’ll see in the next chapter, the direction marketing has chosen to set needs some serious rethinking.