In the essay, “Making Music a Racket,” from the Winter 2011 edition of online magazine Stir, Mat Callahan argues for the abolition of music copyright and against the criminalization of file-sharing as ways to resist the idea that music can be private property. The author of The Trouble with Music and a veteran musician, Callahan is passionate about the anti-individualistic nature of music and its manipulation by a profit-obsessed music industry. In the following interview, the former San Franciscan and now Swiss-based author discusses copyright, music as community, and how music has become a “stalking horse” in the corporate world’s fight to promote and commoditize intellectual property rights over open access.

Why should copyright be done away with, especially in regards to music?

The simplest answer is that it’s unjust to the creator — contrary to what is popularly imagined. If we’re going to find a system that is just, if we’re going to find some way where credit and just compensation are actually awarded to all the people involved in creating a song, putting on a performance, or doing something creative, then we need to get rid of this system, because the system prevents any alternative. It will not allow it. If copyright is done away with, then something new can be constructed. That’s why I call for its abolition.

This year, we’ve seen Mutual Aid in Motion.

From scaling sharing hubs to Mutual Aid 101 trainings, we’re helping communities build the tools they need.

Every dollar fuels lasting resilience – proving that when we move together, we all move forward.

It’s not that I don’t think that musicians, songwriters and composers should be compensated. But I don’t think it has anything to do with ownership. These are not things that are owned by the composer; they’re simply things that are created by the composer, and there should be credit assigned to that labor and that imagination. At the same time, the way the system excludes many of the people that are actually necessary to the creative process, but never get credit.

This is the classic example that I give in my book, and it’s represented in the film “Standing in the Shadows of Motown,” which is a film about the band (The Funk Brothers) that actually made all of those great hits, but none of them ever got any credit, although they composed most of the music, aside from the melody and the text. Maybe the melody is really nice, and maybe the lyrics are nice, and so on, but it wouldn’t be the same music. And yet, they were given no credit at all. That’s the way the system presently functions. A lot of people who are involved in the creative process get no credit and if they’re compensated, they’re just paid a day’s wage, or whatever.

The way the system is operated now, the overwhelming percentage of money goes to publishers, to record companies, and to people that actually have nothing to do with the creative process at all. A very small share goes to the actual creators, and even that share, the largest part of that small share goes to a few stars. There are a few very famous songwriters, like the Beatles, Elton John, who collect large royalties and are very happy with the system, but there are literally millions of songwriters who don’t get compensated at all, or who get compensated very little, and so the inequity of the system, which is what copyright was designed to enforce, is what has to be eliminated.

That reminds me of the comparison that you made in your essay between Joe Hill and Irving Berlin. They were both taking songs that previously existed and using them to make something new. How does the difference between these two composers fit into your argument about copyright and why specifically did you talk about those two people?

In Irving Berlin’s case, he was involved, along with a few other famous composers, with really defining the Copyright Law of 1909, and the way it was actually propagated through the music business. In the case of “Alexander’s Ragtime Band,” which was one of his first hits, he was actually appropriating the music of black people; this is a classic example of what’s happened throughout the history of the United States. The underlying basis of what we call American popular music, its biggest influence was the music of African-Americans, whether it was blues, jazz, soul, or gospel. The majority of the songs, melodic and rhythmic ideas derive from those sources, and those people have never been credited or given any kind of compensation.

I’m a musician myself and so I really related when you were talked about music as community and how music is inherently about sharing. It’s not a business. It’s about bringing people together who have this common love and sharing what you know, and teaching each other how to play, sharing songs. To make it into a business totally alters everything. Can you speak about this concept of music as community?

Fundamentally, that’s what art does, not just music. But music in particular has this role of, whether it’s accompanying poetry, or dance, or if it’s used in a ritual, or a ceremony, or any number of other practices that are universal — all human beings do these things. Its function is not for buying and selling. Its function is to unify a community. If it happens to be that you’re living in a modern city somewhere, and you just happen to be a lover of Free Jazz, well that’s your community.

It might be a very small community if it’s experimental music, but it nevertheless has this function of bringing people together to share something that they value. The value is not monetary, the value is not financial, the value is in lived experience. These things don’t translate in any logical sense into numbers. There is no quantification involved. It’s a quality that’s being produced, and without that quality it would not be musical. Without that quality it wouldn’t interest you, you’d be bored. It’s not about the numbers, whether they’re a number of dollars or how many downloads were created, or how many millions of songs you can put on your iPod. It’s about the quality of the experience. Of course, this is completely against the whole “bean-counter” mentality of the music industry, where all that they’re interested in is how many units have been sold.

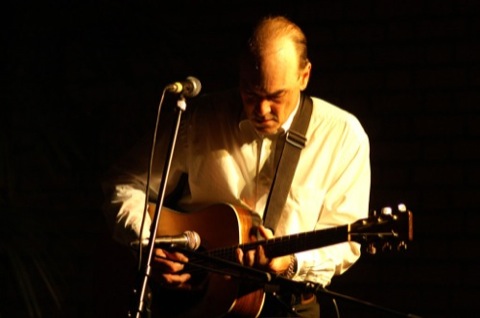

Mat Callahan at Garden Restaurant Eisenwerk, Frauenfeld, August 18, 2007. Photo by Patrick Frischknecht.

In your essay, you defend file-sharing, calling it a continuation of what people have been doing for centuries with music — sharing it with each other.

Yes, I mean, that’s it. Fundamentally, music is an activity. Built on that activity are the results, you might say, the songs, the actual compositions, which then can be shared in one form or another, either on the printed page in terms of sheet music, or in a cassette, which was the original bogeyman of the music industry. They threatened the death of civilization because cassettes were being shared, and now we have it with digital downloads. In fact, the largest number of playlists are created because people are music lovers. They’re not exploiting them for commercial purposes. They’re just sharing their music.

Given the scope of the internet, and given that you have this vast number of people who can actually be accessed world-wide, of course that freaks out the industry. One of their ways of maintaining control was through distribution, and it’s now being undermined. They still do control distribution though. And the fact is that if they want to they can shut down the internet. We see that in China and other places. That may be in the end what they do, put severe limitations on freedom of access just because they want to control copyright.

The dirty little secret in all this stuff is that what they’re really interested in is much more than music. Music in that sense is actually a fairly small percentage of what’s at stake, and what’s at stake, of course, are patents. You’re talking about food, you’re talking about pharmaceuticals. You’re talking about closing the commons. The vast fortunes involved with Monsanto and genetically modified food or various pharmaceutical companies being able to control or access the traditional knowledge from Amazonian plants to South African herbal medicine, that’s at stake. But in the wealthy countries of the North, music is a great stalking horse because they know so many kids are involved with it. They need to convince young people, the new generation, that their future lies in defending intellectual property. That’s the ideological offensive….to convince everybody that you can own an idea into perpetuity. You know, I wrote this song so not only me but three generations down the road, my great-great grandchildren will own this song.

Which is so ridiculous. All songs are informed by songs that came before. How do you own a song? Just like how do you own a plant, or what’s next, water?

Exactly. This is exactly why this is so dangerous from the point of view of the entire structure of legal definition of the individual, legal definitions of private property. This is at the heart of it because you know, music is in some ways the ideal embodiment of ideas because it doesn’t exist except as it disturbs the air. An object, a piece of paper, a CD or a file — that’s not music. Music is in it and it can be delivered, but it’s not music until it comes out of a speaker and it disturbs your eardrums. That’s also true of ideas, although somewhat indirectly since they often exist on paper.

Thomas Jefferson lobbied at the time of the American Revolution against copyright. He gave the famous example that you can’t own an idea. Something like, an idea is like the fire on my candle and if I light your candle it doesn’t diminish my light, it only extends your light. That’s metaphoric but it’s actually literally true. Ideas don’t exhaust themselves. They’re not like land, or some other material object that can be exhausted.

To compare an idea, whether it’s musical or philosophical, with a material good such as a rock or gold, or something, is insane actually. It’s illogical. It can’t be supported in any kind of practical sense, but the entire intellectual property system is built on that. So, what you’re dealing with is this fiction. It’s a fiction that was created and then enforced so that everybody would accept this fiction as fact. But it’s not actually a fact. It’s become a fact in the form of law. These conventions and treaties that were signed and then propagated in various countries. They’re not only impermanent, and they certainly didn’t exist very long ago, but they’re not permanent in the future either, there’s nothing that says they should remain.

Image by opensourceway.

How might musicians receive credit and compensation outside of the free market economy?

In terms of credit, you kind of have to do away with the legal definition of the composer, because the composer corresponds directly in law and in practice with the individual, which is the legal construction that goes back to the original copyright act of 1710 (Statute of Anne), which was based on John Locke’s definition of the individual.

First of all, the individual doesn’t actually exist except in law. Individuals owe their existence to their parents, communities, the societies in which they live. So the idea of the individual as an isolated atom is questionable on its face. When you look at a piece of music, and you say the composer is the most important element, you’re creating an artificial distinction that doesn’t exist in the making of music. It doesn’t take away from the role that a Mozart or a Beethoven, or for that matter, a John Coltrane, played in composing music.

When I write a song, I certainly have been the one responsible for assembling the melody, putting the notes together, figuring out the way the rhythm should work. But when that music becomes music, and is not just my idea, it involves other people. At the very least, even if it’s a solo singer-songwriter, it involves the audience and a relationship between the performer and the audience, and a relationship between the performer and all of the influences in their background. Obviously, you see with the more ethically inclined musicians, you’ll see them giving credit on their records. They’ll give thanks to so and so. There’s already a spontaneous desire for people to give credit for the work that they’ve done, but I think that this should become the rule and not the exception, or the nice thing that you do because you’re a nice person, but in fact credit should be defined by all of the people who have contributed to making this music.

Perhaps the leader should be given more credit, or put in larger letters at the top, but it should be kept in mind that it’s not just an individual. It’s rare that an entire musical production is one person’s work alone.

The second thing about compensation is that if we keep a cardinal rule in mind, and that is that the people pay for everything. Whatever it is, we pay for everything. The question then is: How is that payment distributed? What is the right way to pay composers or musicians for their contribution to society? What is the fair way to do that? That’s something that should be determined by society. If we want music and art, we will have to support it. It’s not a consumable good, in the manner of food, where you put labor in and you get nourishment out. We have to recognize that as a society, whether through tax money or patronage, we have to be willing to support the arts without it being a commercial good, without it being profit-making.

In that context, the artist who’s not simply doing it because they love to do it, or has special talents or special abilities need to be sustained, they need to make a living. So how do you do that? Well, there are different ways. You could — following the classical music model — say governments and rich people pay for opera houses and pay for the artists, which is already happening. Why not extend that to all music? Why is popular music considered a marketable good and therefore has to succeed or fail based on how many units are sold? The point is that it’s already recognized that art is not self-sustaining in the economic sense. Society will have to support it and decide to support it. The part that makes it very mysterious, is that in the 20th century popular culture turned into a very profitable business, especially movies and music.

Music itself was not a really big deal until World War Two. It was profitable but it was really small potatoes. We’re dealing with a culture now in the 21st century where popular music has occupied a place that’s very profitable. We have a star system and American Idol and we have all this other stuff to keep propagating this business, but that’s not actually necessary. We don’t need any of that to have great music. In fact, it gets in the way of great music. It takes up the space that great music would fill and amend. Along with getting rid of this whole copyright system, and the star system, and privileged rich and poor musicians, you would fill it out with something that is far more egalitarian.

This doesn’t mean that everybody who says “Well, I want to play guitar,” should make a living from it. There would have to be way so determining who actually is worthy of being a professional, if you want to use that term, or worthy of that kind of support. My wife sits on a board in Switzerland where she, along with other professional musicians, determines how money from a foundation is given to young musicians. They come in an audition and play and are given money when it seems that they’ve done their work. They’ve worked hard. You can tell they’re very serious. In principal there would be a way where actual masters, or experienced musicians would be the judges of the future, looking upon younger people and saying, “Okay, well, you’ve paid your dues and now it’s time to reward you, but in return you’re going to have to give society what it needs.”