Citizen science is often a hands-off activity, particularly when it comes to space exploration. There’s a wealth of collaborative projects on Spacehack.org, the clearing house of citizen space exploration projects founded by Ariel Waldman, but those missions remain earthbound. The notion of DIY space travel seems improbable, the foolhardy persuit of eccentric millionares with money to burn and their less-wealthy, but no less obsessive counterparts, who often share more with the South Carolina man who has devoted his life to building a replica flying saucer than Robert Goddard.

[image_1_big]

Kristian von Bengtson is no eccentric. When he talks about DIY space travel, it’s worth taking note. A former NASA contractor and member of the AIAA Space Architect Technical Committee, Bengtson’s plans to build a DIY manned space rocket are more than pipe dreams. Bengtson founded Copenhagen Suborbitals in 2008 with inventor Peter Madsen, a non-profit that aims to democratize travel to the final frontier. Since its inception, Copenhagen Suborbitals has already launched a number of test rockets, most recently the Heat 1X-Tycho Brahe in June:

This year, we’ve seen Mutual Aid in Motion.

From scaling sharing hubs to Mutual Aid 101 trainings, we’re helping communities build the tools they need.

Every dollar fuels lasting resilience – proving that when we move together, we all move forward.

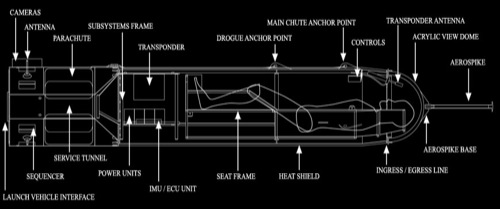

Bengtson and Madsen are building DIY spacecraft they hope will take one of their brave colleagues into suborbital space. The first spacecraft was the Tycho Brahe-1, a one-man standing craft they hand-crafted over a two year period, from 2008 to 2010. As revealed by this schematic, while the view from the ship may have been sensational, the accomodations are far from spacious:

They aim to change that with their latest spacecraft, Tycho Deep Space. Bengston describes the craft as “a half sized Apollo-shaped space capsule with a diameter of 2 meters capable of serving one (or two) persons.” When complete, Bengston hopes the suborbital craft will convey a human passenger higher than 62 miles above sea level, allowing him the rare opportunity to escape Earth’s bonds and view the heavens from the ionosphere. Bengston is blogging about the design and building process for Wired, sharing plans and regular updates from what he’s dubbed the “(space) office”.

[image_2_big]

Traditionally, the comfort of human passengers has been one of the last considerations in spacecraft design, with cost, engineering limitations, and the goals of the given mission taking precedence. Bengston wants to reverse this dynamic with Tycho Deep Space, placing a premium on making the flight “a great experience” for the astronaut. In a post on Wired, he explores the safety and comfort considerations taken while designing Tycho Deep Space, and the difference in philosophy between this project and previous manned space flight missions:

Humans in space were the main driver for the development of rockets during the space race. There is a major political statement about bringing “one of us” into space instead of a satellite or gizmo (well, except being first like Sputnik). At my time at NASA it was still clear to me that humans where a secondary payload and the design process was orientated around machines and not humans… I want to reverse the process. For me, the human being must be the baseline of the design and anything else must be add-ons.

[image_3_big]

While the notion of a DIY space program is undeniably cool, Bengston is a former NASA contractor and has a Master’s degree in Space Studies from The International Space University in France. He’s not exactly a newbie to building spacecraft. But true to its mission to democratize space, Copenhagen Suborbitals is open-sourcing its plans, making similar efforts tantalizingly available to those who lack the specialized expertise of Bengston and Madsen. 3-D e-drawings and CAD files for Tycho Deep Space have been released, with download links available on Wired.

In a TED talk, Bengston imparts “all the secrets of getting into space if you’re broke.”

Bengston signs his reports with the Latin phrase “Ad Astra”, a reference to a Virgil quote which means “to the stars”. Virgil could have scarcely imagined that one day, human beings would actually build machines that could fly them to the stars, much less mere plebians. (For what it’s worth, the scientists and astronomers who worked on the Apollo project probably would have had a hard time imagining this as well.) But with the innovations of the open source movement, the increased availability of fabrication tools, the rise of the maker movement, and the efforts of Bengston and Madsen, the DIY-inclined masses may take to the stars yet.