WHERE HAVE ALL THE SMALL BUSINESS LOANS GONE?

When Sergio Lub, a small business owner in Walnut Creek, submitted public testimony to the Banking and Finance Committee on May 2, 2011 supporting the creation of a state-owned bank in California, he wrote from personal experience, as well as knowledge of the elephant in the room: “…I long for the treatment I used to receive from the former Contra Costa Bank of Walnut Creek. Whenever I needed working capital, I just made a phone call and it was done.

“After our bank was bought by Wells Fargo, getting a credit line became increasingly more complicated to the point that now ― even after being a customer for 36 years ― we no longer qualify for loans. This is because our type of business (handcrafting and wholesaling of jewelry), does not conform with the standard type of businesses Wells Fargo seeks to bundle and easily re-sell to Wall Street investors.

“It is my hope that, as happens in North Dakota, our Bank of California will encourage and support local banks to finance local businesses so we will not be handicapped by the rigidity and restrictions of the big banks. It is ridiculous for us to go begging to East Coast bankers to please capitalize our assets, and then, if we manage to be successful with our plea, to please accept our interest payments.

“Our own California Bank, and the local banks it will help…will more easily understand the value of our assets, including the increasing importance of intangibles like name recognition, know-how, and customer loyalty, which are now being ignored by Wall Street, in spite of being often the most valuable part of our businesses (as reflected by any local appraiser). Keeping our money in our own bank will be enough to capitalize our needs several times over, and keeping our interest payments ‘in-house’ will allow us to meet long-delayed infrastructure improvements while lifting us from this unnecessary recession.”

Lub sees what the farmers and industrial workers of North Dakota saw when they noticed where their money went. They formed the Non-Partisan League, won an election, and created a state-owned bank. Those of us living outside North Dakota have been spending much of our hard-earned paychecks on Wall Street’s exorbitant interest rates. (Not much of a return, eh?) As long as there was some regulation of the banking industry, things seemed to work well enough that we didn’t pay much attention to our bankers’ activities. September of 2008 changed all that. We now know that big bank shenanigans (read “fraud”) are rampant. And we know that the bailout’s proposed effect ― to foster big bank lending for small business growth and its attendant job creation ― hasn’t happened. Instead, the big boys are even bigger and many community banks are struggling, except in North Dakota, of course.

But if we had a widespread, well-operated, transparent, publicly owned banking network in place, the private banks would have to behave, or they would simply go out of business for failing to even come close to the standards set by their public counterparts. There would not have been a crisis in 2008 if we had such a public network.

The New York Stock Exchange on Wall Street in New York City. Photo credit: Chris Brown. Used under Creative Commons license.

FROM DEBT TO WEALTH

Compounding our debt to private megabanks has carried us into dangerous waters. It’s time to compound our wealth by creating publicly owned banks. Public banks restore the issuing of credit as a public utility while supporting local and regional economies. States and municipalities are able to reclaim their money supply and exit the web of debt by creating a self-regenerating regional economic system. This alternative avenue for credit-worthy individuals, communities, counties, and states to obtain funding will put our tax dollars, and other public funds, to work for we the people.

And, yet, the Too-Big-To-Fail Few are demanding that public policy priority should be on spending cuts to get budget deficits under control, not on the banks’ recklessness. The establishment of a public banking network will restore the credit commons so we can support local economies up to the state level. Instead of bailing out big banks, we could be revitalizing our neighborhoods.

HOW DO PUBLIC BANKS OPERATE?

A well-run public bank can aid state and local governments in getting through cash crunches without massive layoffs, privatizing public assets, or cutting back public services. Since creating local economic resilience is the motivator ― not just creating profit ― the focus of public banks is not short-term lending, but rather long-term loans to finance socially beneficial projects that are not profitable in the short-term. Public banks also partner with community banks, as our friend Sergio stated in his testimony.

The economy is suffering from a massive shortage of money because about 97% of our money comes from bank loans, which are a scarce resource these days. To create the jobs we need to thrive as a society, we can do as the American colonial governments did: States and municipalities can take on the lending functions of banks to boost their primary economic driver(s), and to help their citizens prosper.

State legislatures think they have to keep going to Wall Street, hat in hand, for another loan. But those loans include high-interest payments which put the state deeper in debt. Interest payments consume an ever- increasing percentage of our taxes at all levels of government. Those payments are also stifling investment in much needed infrastructure, and are eating the savings of citizens.

Public banks, on the other hand, invest in our needs, not Wall Street greed. Unlike socialism, where the people work for the state, this is the state working for the benefit of the people. The idea is to complement private banking with a public, non-profit alternative. Complete transparency is essential to prevent corruption of this essential public utility.

At no cost to the taxpayer, public banks can finance the public directly. Any interest payments charged by a state bank are plowed back into the state as loans to fund economic development, rather than going to private megabankers. That allows taxes to be reduced at the same time that infrastructure spending is increased. The citizens would save money, and the state would make more money to provide better services and to grow local economies that are more resilient. Over time, even federal subsidies to states would shrink, thus reducing the federal deficit.

We can creatively use public banks alongside private banks to do the people's business. Examples include low-interest loans to students, businesses, and home buyers; the purchase of municipal bonds for infrastructure and economic development; a secondary market for mortgages; and provision of short-term liquidity to private banks, as well as disaster relief and other public purposes. Loans for income-producing projects (transportation, energy, and housing) could be repaid with the profits generated by the funded projects. In all cases, the profits of a public banking institution are reinvested in its capital or returned as revenue to the governmental authority (state, county, or municipal) which established the public banking institution.

Creating a public bank would get the state's frozen credit moving again because it has huge assets and a vast potential deposit base; no big-bonus-taking CEOs or shareholders demanding quarterly profits, etc.; a clean set of books that will be a matter of public record; and a mission statement requiring investment in developing local communities. To keep it public, the bank’s charter will prohibit the bank from ever being privatized. But this is all just an idle dream, right?

Main Street Market on Vinegar Hill, Charlottesville, VA. Photo credit: Villain Media. Used under Creative Commons license.

A PUBLIC CREDIT PIONEER

In continuous operation since 1919, the Bank of North Dakota (BND) demonstrates that public banking is effective and is a valuable policy tool to keep economies stable and thriving. Currently, North Dakota ― in part due to the BND’s beneficent influence ― has the lowest unemployment rate in the nation (just over 4%), has no debt to service, has a $1.1 billion surplus, has experienced no bank failures in the state, and is the only state in the last two years to avoid a budget deficit. But they have big oil revenues, you say. So do other small states like North Dakota, but the difference is the BND and its public banking policies.

The BND facilitates loans that commercial banks simply don’t make. It increases lending while avoiding risky loans. (What a concept!) This helps create a self-reinforcing economic loop that grows the state’s economy. For over 90 years, the BND has built strong working relationships with community banks to support family farmers, small businesses, and the state’s economic development. Now that’s a job generator every state could use. Yes, they are holding some bad loans, especially now. But the core of what they do is to protect themselves by setting aside reserves to cover the inevitable loss. So the occasional default on such loans does not affect the overall profitability of the bank.

The BND returned over $350 million to North Dakota’s General Fund in the last decade, easing pressure on the state budget. For a state with a population of about 600,000 people, that’s considerable cash. Imagine the revenue the bank of a more populous state could generate (as well as save), thereby allowing taxes to shrink over time.

It also acts like a bankers’ bank or mini-Fed for the state’s financial system, supporting the operation of its other financial institutions. The BND helps community banks out in a pinch, clears their checks, and also buys loans from them when they’re either beyond their legal lending limit or they want to share risk. The BND is also a secondary market for residential loans. This is how healthy economies are nurtured and maintained. North Dakota has beaten the Wall Street credit freeze by generating its own credit.

As for job creation, areas with more small banks tend to have more small businesses. North Dakota has more local banks per capita than any other state. By serving as a secondary market for loans to aid local banks, BND has contributed to this economic fertility which maintains the viability of credit-worthy local businesses.

The BND participates in loans originated by local banks and credit unions, either by increasing the total size of the loan, buying down the interest rate, or providing loan guarantees. According to their website, the BND offers “below market rate of interest to start up, or to troubled borrowers within the state.” Some of their business loans are “tied to new job creation as a requirement to get the loan.” And all its deposits are guaranteed by the state. If North Dakota can do it, so can other states and municipalities, and they can do even more.

MOVING BEYOND THE BND MODEL

At minimum, a state bank can be a banker’s bank, and assist community banks and credit unions to lend more by guaranteeing portions of their loans. Beyond that, it’s up to each state’s wisdom and imagination.

Here are some possibilities:

1. Stimulate the economy by prioritizing the creation of essential jobs;

2. Cut investment costs in half or more with low-interest financing for homeowners and businesses;

3. Make health care affordable;

4. Issue import-replacement loans to develop in-state versions of products that are currently imported;

5. Issue credit cards at affordable interest, say 6%;

6. Tie a portion of the increase in state revenues from the bank to tax reduction;

7. Offer zero-interest loans as community equity loans for public infrastructure/benefit;

8. As the Ithaca Hours Bank does, offer such loans to individuals for home improvements, etc.

A public bank based on the model of the Commonwealth Bank of Australia would be a massive community currency system (operating on the people's credit), and a massive credit union and cooperative (owned and run by and for the people).

WHAT ABOUT START-UP CAPITAL?

A bank must start with capital. This takes the form of bonds issued for the purpose of capitalizing the public bank or an appropriation of funds to be repaid from the bank's profits. There are several funding options: existing tax revenue, state and municipal CAFR accounts (government savings funds), and public assets.

WHAT ABOUT CORRUPTION?

From the BND’s website, “To minimize the possibility of political meddling, the bank publishes annual and quarterly reports detailing its finances.” In addition, the people need to be established as the proper shareholders of the bank, with the bank board directly elected by the public. Only public money may be used for the campaigns. This elected board will provide policy direction and oversight to ensure that the bank performs according to its charter, which must spell out how the bank will support the public interest. Terms for board members should overlap to ensure institutional memory.

It would be best if public banks were required to use transparency accounting standards so as to trace how proceeds of public banks flow into the local and national economy. Shine a light on every deal. Post all documents relating to every transaction on a website.

A NETWORK OF PUBLIC BANKS

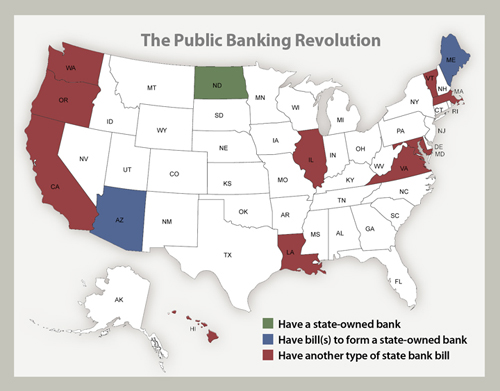

Twelve states are already considering creating a state-owned bank ― Oregon, Maine, Arizona, California, Washington, Illinois, Louisiana, Virginia, Vermont, Hawaii, Maryland, and Massachusetts. Sister public banks could align and strengthen their efforts, exchanging exposures among themselves so as to self-insure. Through networking them, we will create a national community credit-generating system, a large source of investment dollars that has been sorely lacking. That would transform the ongoing race to the bottom into prosperity for all.

LEARNING MORE

For additional information about public banks, feel free to visit the Public Banking Institute’s website. Also check out PBI's 59 page public banking legislative guide, "Public Banking in America Legislative Guide".