Claro Partners' project Changing Models of Ownership and Value Exchange sought to understand how the concept of ownership and its transfer have changed – and are changing – in recent years. This is one of three short articles which Shareable will publish this month, featuring content from Claro's latest work.

From cars to CDs, houses to handbags, people are no longer aspiring to own. Belongings which used to be the standard by which to measure personal success, status, and security are increasingly being borrowed, traded, swapped, or simply left on the shelf. Various factors – arguably the most important being an increasingly connected and digitally networked society, regardless of economic development – are causing revolutionary global shifts in behavior. As quickly as a new laptop becomes yesterday’s technology in a brittle plastic shell, or a power tool idly collects dust in the garage, it seems that material possessions are changing from treasure into junk, from security into liability, from freedom into burden, and from personal to communal.

Through global research conducted as part of an investigation into the concept of ownership, Claro Partners was able to draw some conclusions about why it’s more appealing to have a car only when you need to move from A to B. We also started to ask questions about what new challenges people face in a climate where transient access to services – rather than permanent acquisition of products – is more efficient and actually makes more economic sense. Furthermore, from the cloud to the crowd, we asked whether the concept of ownership is even applicable to today’s world.

This year, we’ve seen Mutual Aid in Motion.

From scaling sharing hubs to Mutual Aid 101 trainings, we’re helping communities build the tools they need.

Every dollar fuels lasting resilience – proving that when we move together, we all move forward.

Ownership becomes a burden

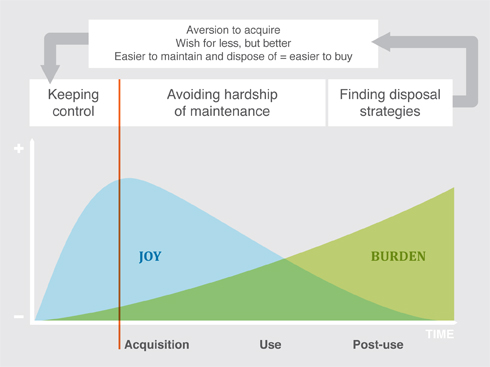

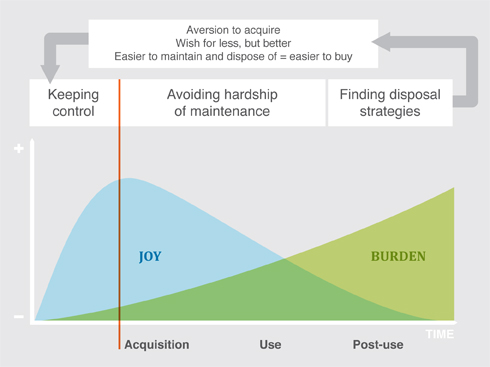

In societies saturated by hyper-consumption, the joy of acquiring, of holding the new object in your hands and knowing with satisfaction that it’s yours, is familiar. Equally recognizable, though, is that creeping anxiety when the sheen starts to fade and your mind gets distracted with a new, better, life-improving version, and at this intersection, ownership becomes a pain, a burden. The product’s value becomes outweighed by concerns of maintenance, optimization of use, and finding a good home for your once-loved product, be it through recycling or re-use. This cycle seems to be becoming ever-shorter, especially in the Western world where gadgets rule and electronics are designed to fail, and both people and businesses are developing strategies to deal with the highs and lows of ownership.

The trade-off of ownership for access

Despite the infinite diversity of the human race, we’re actually quite similar in the kind of things we want to achieve on a day-to-day basis and, collectively, we’re beginning to realize that there’s little reason not to share the resources necessary to achieve these goals. With increased connectivity through modern technology, networks at both a global and local level are growing rapidly whilst new communities can develop and flourish through digital channels. These, in turn, allow for resources to be shared, swapped, borrowed, and traded while providing a platform where exclusive belongings are simply irrelevant.

As suggested by Rachel Botsman in What’s Mine Is Yours (2010), four factors – environmental concerns, reduced spending power, the resurgence of communities, and new technological platforms – have facilitated the rise of collaborative consumption and, in the current climate, alternatives to ownership are starting to seem like a good trade-off for not having the CD on your shelf or the car in your driveway.

Equally, this environment encourages new systems to grow organically from the bottom up, naturally streamlined and designed to be resilient from the start. Effectively, access to the products or the means to achieve a specific goal has become good enough in these circumstances and a viable and appealing antidote to individual ownership. Of course, Shareable.net is both an expert and a product of this movement and many examples of this approach to consumption/acquisition/life can be found within the pages here.

Filtering the data we can access

Replacing ownership with access is not without its challenges to consumption, however. As well as providing a platform on which to connect with people, the Internet has provided us with more data than we could ever want at our fingertips and, consequently, means that we have to spend effort in handpicking what we really want to focus on.

As stated by Seth Godin and later quoted by Chris Anderson in Free (2009): every abundance creates a new scarcity. Our finite time and attention is faced with a sheer abundance of information wanting to be found, read, heard, watched, and consumed, and we are faced with the problem of digital noise. Unfortunately, one Googler’s junk is another Googler’s treasure, and that means there’s no one definitive filtering solution, so people are adopting their own systems to deal with the influx of information, driven to use various ad-hoc methods to curate the content they encounter.

For example, in Sao Paolo, we spoke to someone who no longer reads newspapers and magazines, but instead displays constant Twitter feeds from friends on a large TV screen for a source of real-time news with the added value of the attached commentary. Another tech-minded interviewee in San Francisco collected films based on their ratings on a collection of trusted movie review sites and another relied on his network of friends for the latest YouTube memes.

Social networks play an important role in the filtering of the constant flow of new data; according to a recent study, 48% of young Americans find out about news through Facebook. Likewise, strategies for streamlining belongings are being applied to the physical world, where quality and access are ruling over quantity and material possessions. A U.S. research respondent consciously subscribed to a “less stuff, but better stuff” lifestyle, making decisions to acquire, consume, and keep only the things that he saw to be of value and never a burden.

Is digital ownership an oxymoron?

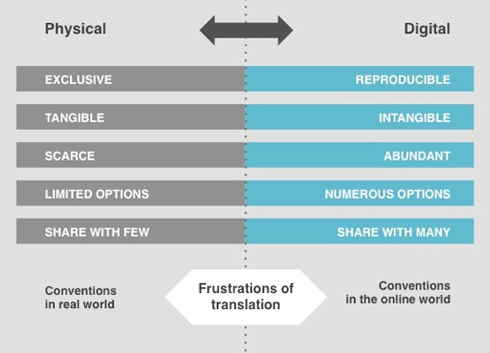

If we are busy creating, posting, storing, and investing in this exploding global community, do we own the results? How can the conventions of ownership in the physical world even be applied to the digital? Take a photo, for example: a negative or print is original, hard to replicate and will depreciate over time. Its digital counterpart is the inverse and these factors enable it to be owned – or be in the possession of – many people at once: it’s infinitely shareable. These rules of the digital seem incompatible with traditional concepts of ownership and many attempts at the application of artificial constraints to digital material have raised questions and conflict. This discord lies at the heart of digital piracy and is a grey area across societies touched by technology… that is to say, everywhere.

Ownership of a virtual presence

Participating in global networks, online or off, is facilitated by a virtual profile which needs to be controlled and maintained, along with the data with which it is linked. It’s easy to keep a bunch of photos in a box on a shelf in your house (with the embarrassing ones of you sporting questionable fashion or scoffing cake at your eighth birthday party safely hidden under all the rest), but keeping track of the same pictures digitally is another matter.

Apart from pictures, there can be all the personal data about you, your bank account, and your professional life history out there on the cloud, not to mention the content you’ve spent time generating, from playlists to forum posts, that is a fully replicable, perfectly preserved part of you. There are various, incompatible strategies already emerging to help the individual keep track of – and capitalize on – their data, some of which will be discussed in our next post. However, in the context where ownership is a synonym for control, there are restrictions and loopholes affecting whether something can be fully owned once having entered the online domain. Just ask Mark Zuckerberg.

Trust and reputation

Once a presence is established within a bigger network, be it through the Internet or at a more basic technological level, elements of trust and reputation become crucial to transactions between nodes (between buyer and seller on eBay, for example). To facilitate these communications, the individual’s virtual profile provides an important point of reference, enabled by platforms designed to provide a history of past interactions. Trends seem to point to a future with an increasingly networked system, linking social profiles with shopping, health, and political records, which could tread the fine line between trust and transparency.

In the context of building a reputation online, we spoke to a research respondent in China who had started trading items on an auction site under her father’s credit card and name. She built up a reputation and profile so credible that she continued to use her pseudonym even after becoming old enough to open her own account because it had such a high market value. To invest in an online profile or consistent virtual identity can pay real dividends and it can actually be detrimental to the owner if this identity is neglected or disowned. Many people we interviewed were concerned about losing control of their data and were wary of companies – new and established – and their handling of information, although they often judged the trade-off worthwhile and continued to opt-in to a proactive role online.

In response to dilemmas and opportunities arising from the global changes affecting ownership outlined above, new business models are emerging which tackle opening gaps in the market with varied success. Their evolution will be influenced both by developments in technology as well as the shifting expectations and needs of societies. We will look at how these businesses are responding to the factors outlined above – and how they might develop in the future – in next week’s post.

##

Check out all posts in the series: