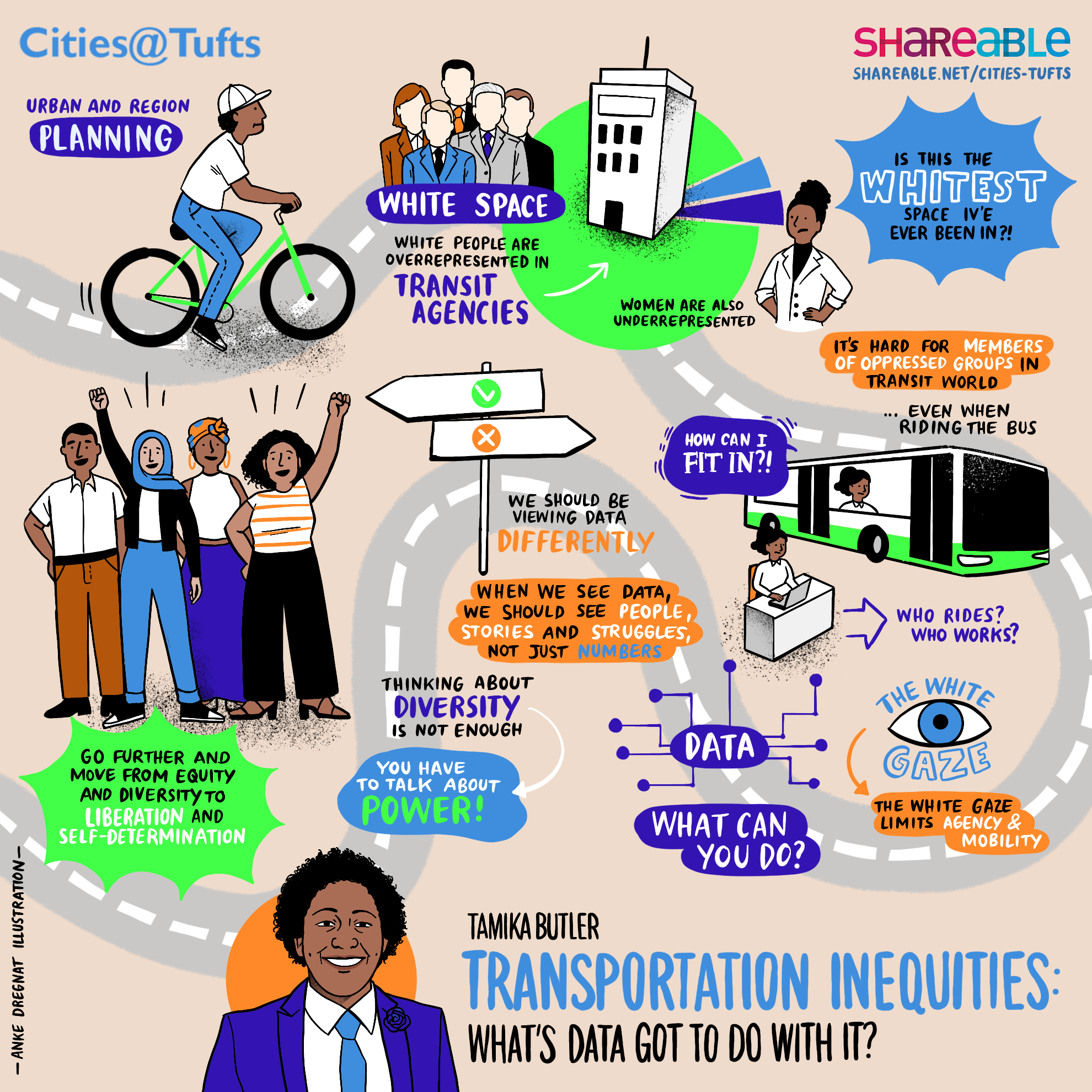

We have included the transcript, graphic recording, audio, and video from “Transportation Inequities: What’s Data Got to do With It?” presented by Tamika Butler on March 30, 2022.

About the presenter

Tamika L. Butler is a national expert and speaker on issues related to the built environment, equity, anti-racism, diversity and inclusion, organizational behavior, and change management. As the Principal + Founder of Tamika L. Butler Consulting she focuses on shining a light on inequality, inequity, and social justice. Most recently, she was the Director of Planning, California and the Director of Equity and Inclusion at Toole Design. Previously, Tamika served as the Executive Director of the Los Angeles Neighborhood Land Trust, a non-profit organization that addresses social and racial equity, and wellness, by building parks and gardens in park-poor communities across Greater Los Angeles. Tamika has a diverse background in law, community organizing and nonprofit leadership. She is currently pursuing a PhD in Urban Planning at the University of California, Los Angeles. Tamika received her J.D. from Stanford Law School, and received her B.A. in Psychology and B.S. in Sociology at Creighton University in her hometown of Omaha, Nebraska. She lives in Los Angeles with her wife, son, and daughter.

About the series

Shareable is partnering with Tufts University on this special series hosted by professor Julian Agyeman (Co-chair of Shareable’s Board) and Cities@Tufts. Initially designed for Tufts students, faculty, and alumni, the colloquium has been opened up to the public with the support of Shareable, and The Kresge Foundation.

Cities@Tufts Lectures explores the impact of urban planning on our communities and the opportunities to design for greater equity and justice.

Register to participate in future Cities@Tufts events here.

Listen to the Cities@Tufts Podcast (or on the app of your choice):

“Transportation Inequities: What’s Data Got to do With It?” Transcript

Tamika Butler: [00:00:06] Data is huge. If data is going to let us break down impacts on individuals in different populations and if we can use data to decide where we need to go and help us figure out how we’re going to get towards those goals, then we have to know the dangers of it. We have to know that there are biases in our data. We have to think about who does the data represent, who’s representing and who’s doing the data. And if we just create data in the absence of social context, then what does our data really mean?

Tom Llewellyn: [00:00:42] Can a Cooperative Cities framework address the unequal impact of automated traffic fines in Black and Brown communities? How can alternative land governance models help us respond to our climate challenge? And is there an equity measurement scheme that can bring clean energy programs and investments to frontline communities? These are just a few of the questions we’re exploring this season on Cities@Tufts lectures, a free, live event and podcast series will explore the impact of urban planning on our communities and the opportunities to design for greater equity and justice. I’m your host, Tom Llewellyn.

[00:01:18] In addition to this audio version, you can watch the video, check out the graphic recording and read the full transcript on Shareable.net. And while you’re there, please take some time to get caught up on all of our past lectures and are ever-expanding library of stories, podcasts, how-to-guides and other resources. And now here’s Professor Julian Agyeman, who will welcome you to the Cities@Tufts Spring Colloquium and introduce today’s lecturer.

Julian Agyeman: [00:01:53] Welcome to the Cities@Tufts Colloquium, along with our partners, Shareable and the Kresge Foundation and the Barr Foundation, I’m Professor Julian Agyeman. And together with my research assistants, Perri Sheinbaum and Caitlin McLennan, we organize Cities@Tufts as a cross-disciplinary academic initiative, which recognizes Tufts University as a leader in urban studies, urban planning and sustainability issues. We’d like to acknowledge that Tufts University’s Medford campus is located on colonized Wampanoag and Massachusetts traditional territory.

[00:02:27] Today we are delighted to welcome Tamika L. Butler. Tamika is a national expert and speaker on issues related to the built environment, equity, anti-racism, diversity and inclusion, organizational behavior and change management. As the principal and founder of Tamika L. Butler Consulting. Her focus is on shining a light on inequality, inequity and social justice. Most recently, she was the director of Planning California and the Director of Equity and Inclusion at Toole Design. Previously, Tamika served as the executive director of the Los Angeles Neighborhood Land Trust, a non-profit organization that addresses social and racial equity wellness by building parks and gardens in park-poor communities across Greater LA.

[00:03:15] She’s got a diverse background in law, community organizing, nonprofit leadership and is currently, I’m delighted to know, pursuing a PhD in urban planning at the University of California, Los Angeles. Tamika received her J.D. from Stanford Law School and a BA in psychology and BS in sociology at Creighton University in her hometown of Omaha, Nebraska. She lives in Los Angeles with her wife, son and daughter. Today’s talk is “Transportation Inequities: What’s data got to do with it?” Tamika, a Zoom-tastic welcome to the cities at Colloquium. As usual, microphones off and videos off. Send questions through the chat function. Thank you. And Tamika, the floor is yours.

Tamika Butler: [00:04:00] Thank you so much for the warm welcome. Thanks for having me. I’m really excited to be here. I’ll try to wrap up my comments in about 30 minutes and leave plenty of time for questions. Looking forward to hearing from you all much more than myself. So with that, let me share my screen. So I am, like I said, absolutely thrilled to be here and to talk to you all a little bit about transportation inequities and what role data plays in that. And so let’s get started. Let’s just jump right in.

[00:04:37] So for folks who haven’t heard me speak before, are wondering why I’m here and why I’m speaking, as you heard in my intro a little bit, I’m Tamika. I love bicycling. That’s how I got into transportation. I personally just started biking and I had a job at the L.A. County Bicycle Coalition, and it really opened up this whole field of urban planning for me. I have to be honest that I don’t know that I knew urban planning existed. There are so many things about our built environment I just took for granted. Sure, someone was making decisions about how things looked and how things moved and how things work. But I never really thought about it. And once I was at the Bike Coalition and realized there was this whole field of folks, many who didn’t look like me or have my life experiences planning where we could go and not go, and who could sit on a park bench and who couldn’t. And how you build that park bench to make sure some people don’t sit there. I knew it was something I really wanted to do.

[00:05:35] And so I had a few jobs at nonprofits, had a private consulting job. And then ultimately when folks ask me who I’m with, I have my own consulting firm, Tamika L. Butler Consulting. And I do a number of things. I work with agencies and big national organizations. So that first report is one I co-wrote for NACTO, one of our big organizations that brings together transportation officials from different cities. They have a big conference every year. And luckily this year it will be in the Boston area. That middle one is a report about climate. I do a lot of climate work. Yes, transportation is my home and my foundation. But naturally I do a lot of work around climate and sustainability. And then also writing and leading a research project for another agency like Metro Link, our regional commuter rail here and really looking at how they could think about accessibility and affordability post-pandemic with a specific focus on fares. I also do some freelance writing for bicycling and work with a ton of tech companies doing some emerging mobility stuff. And because my background is in the nonprofit world, I try to work with as many nonprofits as possible and often help participate in projects or help with writing reports about different topics. And then I do things like today where I love to speak. It’s been a while since I’ve done one of them in person, but I enjoy welcoming you all into my home and doing them over Zoom.

[00:07:11] So a lot of folks ask if I’m a planner and as I said, being a planner is not something I knew about. I was a kid who got relatively good grades, who had two parents who hadn’t gone to college, and they said be a doctor or a lawyer. So I did. Law school was shorter, so I went to law school. And for me, the first time I really started thinking about transportation was as a lawyer. I was working in San Francisco in Bayview/Hunter’s Point, one of the historically Black communities there. And I wanted to help everybody with their legal employment issues. I worked at a legal aid office helping with employment discrimination, and no one wanted to talk to me until they knew how I felt about SFMTA’s New Muni line that was going into Bayview Hunters Point. A lot of folks thought it was just for tourists who wanted to see the San Francisco 49ers play at Candlestick, which was located in the community. But a lot of folks didn’t think it was for people in the community.

[00:08:11] And really it was the community members and Bayview, the church I went to all the time and did my legal clinic and got to know the parishioners. It was them that helped me understand the way that transportation is, as our mayor here in LA has sometimes says, transportation is the prism through which we can see all other social issues. How do you have economic mobility without mobility? And that’s something that these folks really taught me. And I kind of became a transportation nerd then, but I didn’t really get a transportation job until the LA County Bicycle Coalition was hiring. I had just done AIDS Life Cycle, a 545-mile ride from San Francisco to LA supporting the LGBT centers in both cities. And I loved riding my bike. Training for that ride reminded me of the freedom I felt on my bike and it made me fall in love with LA. I hated LA. I was here because I had a partner here, but being able to explore the city on my bike really made me fall in love.

[00:09:21] And me being hired was a big deal there. There were some blogs written, as you can see this one, white smoke rising above the downtown headquarters, a reference to the pope, I suggest. Those of us who have been part of bike communities know that in bike communities sometimes we take ourselves pretty seriously. And for me, the L.A. County Bicycle Coalition, still to this day, best job I ever had. I got to be on my bike every day, wear wrinkled clothes and fit in seamlessly. I helped lead a coalition that made LA a Vision Zero City when Vision Zero was still relatively new and our coalition was different than in a lot of cities. We had the biking group, we had the walking group, but we had youth organizations, we had affordable housing organizations, we had community land trusts, we had public health organizations, we had racial justice, civil rights legal organizations. We had a ton of people understanding that folks dying on the street was not just a transportation issue, it was a people issue, it was a public health issue. And we had to talk about it.

[00:10:33] And before our mayor decided not to run for president and then to potentially be ambassador of India, I was going to news conferences all the time. I was helping launch bike share in LA, and I was one of the leaders of a campaign to get our MPO to really have directed specific spending for active transportation. First time in LA County that a ballot measure had specifically allocated money for biking and walking. And if that wasn’t cool enough because I lived in a place like LA, I got to ride a bike with our director of transportation and a producer of Mad Men and check out the Emmys. Our award ceremony was not as dramatic as this last one. This last week, there were no slaps. But our life was good. I really enjoyed that job.

[00:11:36] And then there was a councilmember who was running for council and he was a bike guy. He owned a bike store. A lot of folks in the bike community loved him. I did not love him so much. He had always been rude to me, dismissive of me. Sexist. Racist. And a lot of folks of color and women of color in the community — when it came out that he had been on the dark portions of the interwebs doing and saying all of these things, none of us were surprised because of our interactions with him. What was perhaps a little bit surprising is that it didn’t matter to a lot of folks in the transportation community. A lot of folks in the transportation community felt that at the end of the day, he was still going to make them safer. And if they were going to feel safe, then they could overlook some of these things he did.

[00:12:29] And it was, you know, wow, what about those of us who never feel safe in this person’s presence? But that didn’t matter. It didn’t matter at all because people wanted their bike lane. And that was one of the first times I thought, yo, this space just might not be for me. I thought about it a lot, but that’s when I really felt it in my gut. And I always tell people it’s not because I think that all bike people are horrible. I just happen to think that while bikes don’t discriminate, cyclists do, because cyclists are people and people discriminate.

[00:13:16] And the more I got into urban planning and beyond just this narrow piece of the bike world and really learned more about just what we do, I just started constantly questioning, is this the whitest space I’ve ever been in? And not saying a lot because I’m from Omaha, Nebraska. So if I think this is the whitest space I’ve ever been in, you know, I just started looking at the data. What is the most common race of urban and regional planners? White folks. White folks are actually more prevalent in the profession than they are in the general population. White people are overrepresented amongst planners.

[00:14:04] And when you think of something like transit, who rides and who works at transit agencies? So transit agencies are super important. They give a lot of jobs, but they don’t have the same demographics as the people who ride. A majority of transit riders are women, people of color, people who are low income, people who aren’t just always making lifestyle choices or climate choices, but are really dependent on transit. But the demographics of the people who work there don’t match that. When Transit Center, an organization out of New York that does a lot of great work, I self-disclose them on their board, but when they published that a report a few years ago, women only made up 39% of the transit agency workforce, and there were less than five transit agency CEOs that were women. There might be a few more now, but the boards are still predominantly white..

[00:15:03] And some people may say, well, that’s transit, that’s old school. Like the future of transportation is emerging mobility. And, you know, like I said, I do a lot of emerging mobility work. I’m all in on Super Pumped the Showtime series taking us behind the scenes on Uber right now. I did a lot of work and have a lot of community in the San Francisco Bay area. I’m on the board of a tech company, Lacuna, that does what I think is great transportation work. But at the end of the day, it’s not just transit, right? When you look at when Uber first released their stats about who made up their company, it was more men, t was more white people. No different than transit. What about when you look at leadership? The disparities are even greater.

[00:15:51] And Uber is fun to pick on because they’re in the news right now as the show is getting a lot of buzz, but it’s not just them, right? When you look at Lyft, they may display it differently and want it to be a little harder to follow, but the biggest circle is still white, folks, right? When you look at leadership again, biggest circle is still white folks. And for me, it’s like, yes, this might be the whitest space I’ve ever been in. Nonetheless, I love transportation, I love planning. So I decided to get my PhD and when I decided to get my PhD during the pandemic, when theoretically we all decided, let’s go back to grad school, I didn’t know if I was going to get in anywhere. My generous introducer graciously served as one of my reference letter writers, but I applied to a few places because I wasn’t sure I was going to get in.

[00:16:46] But one of the places I applied where I ultimately ended up going was UCLA. And as I do as a student of color, when I was applying to UCLA, I was like, Look, I know transit’s super white. I know emerging mobility super white. I know that transportation can be a really wide space. But what’s what’s the academy like? If I’m going to go get my PhD and potentially be part of this academy, what is it like? So, you know, I did my research and these are pictures from the website at UCLA when I was applying. So front and center, they have this commitment to diversity, equity and inclusion. They have a commitment to social justice and to thinking about disparities. They show their demographics right out front. And though it does reflect the highest number, again, being white folks, there are a ton of women there. They even consider non-binary folks. There’s Latinx folks and African American folks. And so, you know, maybe I’ll be okay.

[00:17:48] But then I do what I always do. I go to the faculty page and I see how long I have to scroll before I get to somebody who I think, Wow, is there another Black woman? I don’t see anyone right now. Sure, there is some diversity in the faculty. It’s not completely white. But if you look, it’s still a lot of men. It’s still a lot of white folks. And that’s just what it is. And so when I think it’s transportation and more broadly, because that’s not just transportation faculty, that’s all faculty. When I think of is this a white space? Absolutely, it is.

[00:18:36] And so what does that mean for those of us who want to do planning work and again, not just transportation work, but feel like we’re young and we’re gifted, and I used Black here because I’m Black. But fill in whatever group of oppressed people. How do we think about what this will be for us once we’re in school? When we get out of school, how do we think about advancing? One of your local institutions and the Harvard Business Review, they put out this article last year or the year before 2019, and they just talked about the way that Black folks are still underrepresented in all organizations. And part of the reason is when you are a part of a group that has been historically oppressed, again, whether that’s your race, whether you’re a person with a disability, a queer person, Indigenous, whatever it may be, you have to figure out the ways of white folks. You have to figure out how the folks in charge operate.

[00:19:39] And that means that you’re often code-switching, you’re often figuring out, how can I bring my full, authentic self to work? But how can I still fit in? How can I dress the way I want to dress? How can I talk the way I want to talk? And how can I still be taken seriously? And so many of us code switch, right? And for many of us, that’s why working for home was refreshing because you didn’t have to quite be on in the same way. And people often say to me, Well, that’s not just code-switching, that’s just being professional. We all do it. But you have to realize that some of us do it more. It’s seen for many of us who are members of a press group as crucial for professional advancement. But it has this huge psychological cost.

[00:20:24] And if we’re entering the space that, as I’ve said, is pretty white, we have to understand that there’s just this group of us who feel like we can’t be ourselves in the classroom, in the boardroom, out in the field. Sometimes we feel like we can’t even be ourselves when we’re writing transit. We have to make sure we present in a certain way. I’ll never forget hearing from a foundation director in the Bay Area that when her son asked if he could ride BART, their subway system, by himself and she was like, I don’t know, I’m worried. And he said, Don’t worry, Mom, I have a plan. I’ll take a book and I’ll read the whole time. So people know that I’m a good Black kid.

[00:21:09] We feel like we have to constantly be thinking about what the white gaze will think of us. And organizations stay white and fields like planning stay away because segregation is persistent. If you do planning, you know that, you know residential segregation is persistent, but so is organizational segregation. So is occupation segregation. In many organizations, whiteness is seen as a key credential for moving up. And don’t be confused, like whiteness being white, but also acting a certain way. There have been tons of research studies about women who talk about the way that to advance, they’re often told you have to act like these other people in leadership. And you look around and everyone else in leadership is a man and they’re like, Just don’t be so emotional. Don’t be so moody. Right? Things that they think are stereotypically women. So to act like a masculine patriarchal leader, you don’t have to be a man to have whiteness to move up, you don’t always have to be white. It’s easier if you’re white, but it’s still seen as is a key part of moving up.

[00:22:24] And if we’re going to talk about how to change our profession, we can’t just keep having conversations about, well, that’s just a bad apple, that’s just one-off. We have to first understand that diversity, equity and inclusion are not interchangeable terms. Right? Diversity is this. Folks who have seen me speak before, I’ve seen this slide. Diversity is nineties clip art, right? Get as many diverse folks as you can and just sprinkle them in. Put that person in the wheelchair in front, put the white guy in the back and make it pretend like it’s hard for him to see. And then make sure we have lots of women laugh. Be happy, right? But diversity isn’t the same as inclusion because to get to inclusion, you have to talk about power. You have to shift power. You have to shift control.

[00:23:14] We can have diverse organizations. We can have a ton of diverse faces at the table. But if they don’t get to make decisions, if they don’t get to set budgets, if they don’t get to say yes or no to projects or who gets admitted into this class, then do they really have control? And if you can’t get inclusion, then you’re never going to get to equity. And again, you’ve seen me speak, you’ve seen this because I will put this in every presentation and say this is a great visual representation for many people who are new to the equality and equity understanding — that just giving everybody the same thing doesn’t help. But it’s not an accurate picture because it’s not reality of how we start and it doesn’t actually get to where we should be getting.

[00:23:58] Why are we just trying to see over fences and over the barriers? That’s not where we should be at. Instead, we should really be thinking about liberation. I’m not just doing transportation justice work. I’m doing mobility work. I’m doing liberation work. I’m doing abolition work, right? That’s what’s important to me. And even this picture still is tough for me because as I said, we have to talk about power. Too often folks like to talk about equity without talking about power, but who has the power to determine that what these folks want to be doing is watching baseball. Look, I got out of baseball hat. I got out of baseball Jersey. I like baseball. But what if these folks want to play? What if they want to own the team? There has to be some self-determination involved.

[00:24:53] And too often when we’re trying to make decisions, we turn to data. Not to people and their own self-determination. So why is data such a big deal to me? You know, that’s a question a lot of folks should ask. And some folks may even be unconcerned with the presentation and just be really distracted with my casual attire today. My baseball cap and my jersey. What am I even wearing for the serious talk? And I’m wearing a hat from the Kansas City Monarchs and a jersey from the Kansas City Monarchs. And the Kansas City Marks are a Negro League baseball team.

[00:25:40] So why am I talking about baseball during a talk about transportation inequities? Well, one, as I said, I really like baseball. I like sports. I know for some people that are like sport, what is the ball? But for those folks who like sports or like baseball or even casual fans, when you think of the best player of all time, there are some names that come to mind. Maybe you’re not even thinking of the best player of all time. Maybe you’re thinking of the best player right now. Maybe you’re just thinking about a player’s name who you recognize, right? And for a lot of folks, those are white men.

[00:26:20] And baseball is one of the sports that has really taken the lead on analytics, on using data to make decisions. So in some ways, baseball is like planning. We use a lot of data to make decisions. We use a lot of data to figure out the best route, the best solution, the best way to change our built environment to help people, right? We use data. But something that’s been coming up in the baseball world in the last few years is that the data that’s collected didn’t include the data of the Negro Baseball League. And when you do include data from the Negro Baseball League — we have some Kansas City Monarch players here — it starts to reframe who the greatest player is.

[00:27:14] See, data is powerful. It can help us do a lot of things, but I’ve already shown you data about who makes up our profession. I’ve already shown you data about who’s teaching the future of our profession. We know that one of the tenets of white supremacy is that we really value data. And in fact, there’s this belief that quantitative data is better than qualitative data. And we trust data more when it’s created by folks who have certain qualifications and degrees and institutional backing. But again, I’ve already shown you the data of who makes up those institutions. And if we just create data in the absence of social context, if we’re just collecting data without acknowledging that there’s racism and not just racism, segregation and not just segregation, laws prohibiting perhaps some of the best baseball players from playing in the league, then what does our data really mean? Whose history is it? Who is truly the greatest player?

[00:28:27] That’s why data is important, because, yes, it helps us answer questions and gives us a clearer picture, but we have to start asking critical questions. If data is going to let us break down impacts on individuals in different populations, and if we can use data to decide where we need to go and help us figure out how we’re going to get towards those goals, then we have to know the dangers of it. We have to know that there are biases in our data. We have to think about who does the data represent, who’s represented, who’s doing the data. Are we ground-truthing the data with folks in the community? And are we truly understanding the difference between engagement and outreach? Are we just going out like planners love to do and saying we’re going to do solution or solution A or solution B. Here’s some stickers. Tell us what you like. That’soutreach. Or are we doing true engagement? Here’s what our data shows us. Does that reflect what you experience? What do you think is the problem? What do you think is the solution? Data is huge.

[00:29:44] I perhaps ended up in a PhD program based on a simple overreaction. I was working at a company writing for a client a report about law and how laws have been used, specifically pedestrian laws and biking laws — how laws have been used disproportionately to police people of color. And I was working with a colleague at work and we wrote a lot of things down and the feedback we got, the red marks we got from one of the partners at our organization was, These are opinions. These aren’t facts. I don’t see any academic citations. So perhaps I got upset and said, Fine, I’ll go get a PhD and I’ll make some of those citations.

[00:30:32] So I get it — academia and data and field research, all of these things are important. But we have to understand that sometimes when you see data, you see numbers. And when I see data, I see people, I see stories and I see struggles. And I’m not just looking at transportation data to do my work, because even if I go to a meeting to talk about transportation, the people who I’m talking to have so many other things going on in their life. And so as folks who care about any type of planning, any type of issue facing the city, we have to realize that progress comes through struggle. But you can’t be a single-issue person. You have to think about how these things overlap. There’s no such thing as a single-issue struggle because we don’t lead single-issue lives. Thank you. Let’s do some questions.

Julian Agyeman: [00:31:33] I’m still pondering the implications of all of what you said there to make a fantastic presentation. We do have a couple of questions and I’m sure there’s going to be more as we go on. I mean, I want to start off with Roberto Morales Román who says professionalism itself is a white supremacist concept. So it’s a statement. Roberto, rather than a question. Roberto is there anything else you’d like to add to that or would you like Tamika to just reflect more on it? Know.

Roberto Morales Román: [00:32:07] Thank you. No, no, I just wanted to say, this is an issue that I’ve seen come up a lot, even inside equity organizations themselves. Which really seems to be a problem. And I love — thank you so much, Tamika for speaking on it. Right. But when they talk to us about being professional and acting certain ways and dressing certain ways, a lot of times we can get that from even executives of color. That they’re not seeing how the concept itself serves to kind of replicate and cement these white criteria or ideas of what work should be. And that’s what — I just kind of stating that. Thank you.

Tamika Butler: [00:32:54] No, thank you, Roberto. And I think you’re absolutely right. I remember when I first went natural, my grandmother was appalled and she said, How are you going to get a job? You can’t go to work with your hair like that. And my grandmother loves me, but she really strongly believes that to be professional, you have to look a certain way. That’s why things like the Crown Act are important. And we have to realize that, that there are things like a time clock that started on the plantation. So that we knew when people clocked in and clocked out. And so in organizations and in the work we do, we have to always be really, really critical with ourselves. Why do we think this is important? Why do we think this is professionalism? Does it really matter? And really push ourselves.

Julian Agyeman: [00:33:42] Great. Thank you. We have a question from Ezra Mattaridi. Thank you so much for taking your time today Tamika. Could you expound a bit on the consequences we will see for both planners and the public if this vision, your vision, is not fulfilled? I think about cities where growth is being fueled by white affluence. What does our future look like if Black, Indigenous, queer, transgender, gay people of color, insert other marginalized identities, are excluded from planning processes?

Tamika Butler: [00:34:15] Yeah, that’s a great question, Ezra. I think it will look a lot like it looks. I think that what we see in our communities is not an accident. Part of what makes planning so powerful is this country we have that is deeply segregated. You’re talking about neighborhoods, you’re talking about schools — that was part of a plan. We know this. When you look at the history, when you look at post-World War Two — the war brought many people together. For many Black folks, for instance, we got factory jobs that paid well. We joined the military. We had a taste of what it looked like when things were a little bit more equal, but that’s because we were needed. But then after the war, there were these government programs to help people build houses, have homes, build generational wealth, move out to the suburbs. Well, then we need highways to go out to the suburbs. So so much of this was planned.

[00:35:24] But who didn’t get those benefits? A lot of the folks you just mentioned, what did we do when we started talking about urban renewal and getting rid of urban blight? So now we see folks maybe coming back to the cities, as you said, as refueled by perhaps white affluence and kind of this reverse migration. But we’re doing the same things. I think one of the most important things for people who care about planning to do is start caring about history and start owning the fact that our work has been used to perpetuate and further racism and exclusion. And if we don’t start including some of these folks, all of these folks, in the conversation and not just that public meetings. Pay them and encourage them to get into planning. As a young Black kid who cared about social justice, I heard be a lawyer, go into education, go into criminal justice reform. We need to start saying go into planning. This is the place to be. And I think when we acknowledge our history, we will understand that if we don’t change it, we’re going to just keep perpetuating the things and it’s going to look a lot like it already looks great.

Julian Agyeman: [00:36:36] Thank you. Olivia Burrell-Jackson is asking for a little bit more clarification on the difference between engagement versus outreach.

Tamika Butler: [00:36:45] Yes. So I think, Olivia, the way I think about it is outreach is really — we’re just reaching out to tell you what’s going on. And we all have been to those meetings. We put up a public notice. We’ve gotten this funding, we’re doing this project. Here’s what it’s going to be. And sometimes we ask for feedback. Right? But the feedback is still very narrow. It’s like, do you like option or option A or option B. And we’re not ever truly transparent about hearing whether or not they like option A or option B is really going to impact what we’re going to do in the end.

[00:37:20] The difference is with engagement, we still might go in with what we think is the solution, but we’re open to hearing something different. So a great bike lane example. Outreach would be we’re making the streets safe, we’re putting in a bike lane. We can’t decide if we want it on this street or this street. What do you think? We want to take your opinion, but also, just so you know, we’re leaning towards this street and it’ll probably be this street. But we’re coming here to tell you because we want you to know that you’re not going to be able to drive here and blah, blah, blah, blah, blah. Engagement is we’ve seen a lot of sidewalk bike riding and we don’t want sidewalk riding, so we’re putting in a bike lane. And then you go to the meeting and people say, I’m still not riding in a bike lane. I don’t care what street you put it on. I’m not writing in the bike lane because this is a four-lane street where people never follow the speed limit. There are no — there’s just nothing. There’s no — the street has potholes. Put a bike lane there, but I’ll pop a tire. Okay. Whoa. These are different issues. We’re actually engaging now and we’re actually getting to the bottom of it. So it’s being open to a little back and forth and it’s doing it with honesty and transparency. Because it also doesn’t help people if you tell them you’re going to make changes and actually you can’t. Like the funding says you’re going to do this. So it’s a level of honesty and transparency and engagement that isn’t always there with outreach. Hopefully that helps.

Julian Agyeman: [00:38:51] That’s great. Yeah. And the second part to Olivia’s question, how can institutions increase true diversity in the planning sector?

Tamika Butler: [00:39:01] Yeah. So I think all institutions, whether you’re talking about a private firm, a government agency, an academic institution, I think right now equity is really sexy and people really want to do equity work and so they want to get to the results. Let’s do equity and let’s see what the results of doing equity are. And I think sometimes people aren’t looking internally and saying, are we ready to do equity? You can be an institution that says we want more diverse people here. But then a few years later, you’re like, why don’t they ever stay? And it’s because you haven’t necessarily done the work to figure out what about your institution is an equitable or racist or just really not welcoming, right?

[00:39:46] And so I think whether or not you’re talking about institutions or whether or not you’re talking about it as an individual, we all have to examine what does that internal work, what does that system and culture and personal change we have to do? And then sometimes an activity I do with folks is circle of trust and I ask them to write down in a professional setting, who are the five people you would reach out to if you ran into a problem that you really trust to help you think through something tough? And then I have people look at that list and often it’s people who are just like them, right? Same kind of educational background, same race, same gender.

[00:40:21] And the reality is, I think often and planning, we bring people into the fold who we know, who we’ve heard from somebody, who we recognize something on their resume. And as someone who didn’t go to planning school before, ow, let me be clear. You can do planning without a planning degree. Like the homies hanging out on the corner every day, just chomping it up, can tell you everything you need to know about the speed of traffic on that street and whether or not the stop sign or the speed bumps are effective. And so we have to start understanding that, one, we have to do the internal work. And two, we have to start thinking differently about who should be deemed an expert. There is absolutely knowledge which you can gain from learning and reading, but there’s also wisdom and there are many people who have wisdom. And if institutions can start valuing wisdom, I think that would also lead to a change.

Julian Agyeman: [00:41:20] Great. Thank you. Joyce Klemperer. So, so interesting. I love the way Tamika ties it all together in spaces that aren’t always examined this way. And I think that really is very powerful. The question from Stefan building on Ezra’s question, wondering about the benefits for the broader community, for better representation in transportation, what might you say to further show that all people benefit from better designing transportation for all people?

Tamika Butler: [00:41:50] Yeah. I mean, I think the classic example that a lot of folks use for this question are curb ramps — the curb cuts. Curb cuts, sure, might be part of our Americans with Abilities Act. But many of us who are able-bodied have had a suitcase or have had a baby stroller or have had, you know, whatever it may be, just having a tough day, an injury, whatever it might be. And that curb cut is just as helpful to us. And so sometimes people say, well, if we do this equity planning, it’s going to take longer, it’s going to cost more money, and it’s only going to help this specific people. Right? When we think about design, we have to design for the everyman and too often the everyman picture that comes into our head isn’t it necessarily that person in a wheelchair? And so there are many countries who don’t have those curb cuts. But I think this is a good example of when you plan for the folks who are perhaps the most oppressed, the most vulnerable, it really helps everyone.

[00:43:06] Now, notice, I’m not saying a rising tide lifts all boats or whatever that analogy is. I don’t always think that’s the case. What I always tell people is if I’m in a little dinghy with holes and, you know, just trying to get off Gilligan’s Island, maybe I’m adding myself there. But if I have this little dinghy and the tide rises, Beyonce and Jay-Z are going to be good in their yacht. They’re not even going to notice the tide rising. But for me, I may completely capsize. That may be the end of my boat. So I think we both have to think about the folks who have been most oppressed and realize the way that when we plan for them, it can help everyone. But I think sometimes we can’t get stuck in that argument — I recently read a research paper where the person said, If we start planning and really focusing on people of wealth and affluence and getting them to love transit, transit will be better for everyone. And I don’t know that that’s true. And so I think we just have to think critically about these things and ask ourselves those questions. I hope that helps.

Julian Agyeman: [00:44:17] Great. And I’m glad you mentioned the curb cuts effect. It’s really a very important policy principle, and I think it was. Socorro Shiels needs some advice. He, she they says, surviving government spaces as someone thinking about transformation and justice, can you give me some recommendations?

Tamika Butler: [00:44:42] So I think I think surviving any of these spaces — I think government has its drawbacks, but it has its benefits. One of my best friends is is number two at the Department of Public Health in LA County. That’s a big job always. That’s a big job these last few years. And me and my team were doing an equity training for her staff, and something she said to some of her staff that was feeling discouraged was government work isn’t for everybody. It really isn’t because it’s hard and it’s long. And in government work you are working really long stretches for changes that seem really small. But when you make those changes, because it’s government, it’s really hard to change it back.

[00:45:37] And so government work might not be as sexy, but if you can change a procurement policy and figure out how to directly pay folks in the community, that is game-changing and it probably won’t get changed back any time soon. And so I think that first, no matter what space you’re trying to go into, I always tell people to know yourself. Government isn’t for me. I like to talk a lot. I’d probably get in trouble. It just wouldn’t be a thing. So figure out who you are first. Don’t just go somewhere because you want to make impact. And someone else has told you this is the best way to make impact. Because if it doesn’t feel true to who you are as a person, you’re not going to enjoy it. And you won’t do your best work and you won’t make your best impact.

[00:46:21] So first, figure out who you are and then when you’re in a space, something I had to learn through lots of therapy — so therapy is also advice — but something I had to learn through lots of therapy is, we can’t save them all. And that’s okay. And particularly for people who are folks of color or queer or have a disability or part of groups who have been oppressed, the quote I always tell people is, you don’t have to set yourself on fire to keep other people warm. You might change the world. But that doesn’t mean that you’re going to change that person. And you know? All the energy you spend on that person or that agency or that department is energy you’re taking away from your greater purpose of changing the world. And that doesn’t make you a sellout. That doesn’t mean you’re not good at it. It just means that you sometimes have to choose you. So hopefully that’s helpful.

Julian Agyeman: [00:47:16] Thanks, Tamika. We have a question from Lindsey Doswell. Great question. Environmental justice and equity dashboards are having a big moment in federal, state, regional and local decision making. How can planners create news dashboards that are responsible and meaningful? Can these be good tools for public engagement and accountability?

Tamika Butler: [00:47:38] Absolutely. I think you’re right, Lindsey. Dashboards are having a moment. I think a couple of things are happening. Particularly — and I’ll talk specifically about transportation, but I think this applies to environmental justice and I think it applies to equity indexes and kind of across the board. And there are a lot of jurisdictions doing this. San Antonio did this whole process where they came up with equity indicators and then they’re checking in every year. So there are a number of different cities. That sustainability report from LA County’s chief sustainability officer and Sustainability Office, they have metrics and they are keeping track of it. And then LA County just hired a new racial equity person who’s supposed to put together a dashboard. So this is happening everywhere.

[00:48:30] And I think part of it is as technology grows, government wants to use that technology. Again, specifically in transportation, we’ve seen companies disrupt transportation. And I think cities in a lot of ways are trying to keep up. How can we also use technology to keep track of things? And so I think there are a few principles that are really important and there are different groups that put out different principles. I did a project with the LA Department of Transportation, I went in their first year of their scooter pilot. And we talked about different things that matter and we talked directly with community members.

[00:49:07] So I think the first thing is and creating dashboards and indexes, first talk to community people. I think it’s a mistake when entities create them and only after that then show them. Right, we’re going to unveil this big thing. I think the process to get to the dashboard and what’s in the dashboard has to include engagement, lots of it and a lot of feedback. And both from community-based organization heads, but also from folks in the community. And then the other thing is transparency and accountability. You have to keep saying transparency and accountability. I don’t think if you do these things — but it’s very hard to tell how the data is calculated, what gets put in there. So I think open source sharing and constant accountability, constant sharing and knowing that you’re going to have to constantly update people. I think too often we just collect data from people, but then we don’t ever tell them what we do with it. We don’t ever tell them what decisions were made, we don’t ever come back. And so I think it has to be an interactive process. So hopefully that answers that question.

Julian Agyeman: [00:50:14] Thanks, Tamika. So we have a question from the Brown House Watch Party. And for your information, Brown House is where our main departmental offices are — or some of the main departmental offices. So there’s a group of people watching in there. They’re wondering, what are your thoughts on methods of data collection, such as participatory action research and mixed methods research that combines quantitative methods which, as you mentioned, sometimes dehumanize and qualitative methods that redistribute power to those who are most marginalized.

Tamika Butler: [00:50:46] Yeah, that’s a great question. So this quarter, I’m taking a qualitative research class, and I’ve taken some quantitative research classes, and our first reading for this class talked about the way that data collection, quantitative are qualitative, right? And in fact, in many ways, qualitative data collection was the start of it was all about colonialism, right? It was all about taking the other Brown folks and studying them, pointing out why they were the other, why they were not as good as the white folks and creating data as to why you want to change it.

[00:51:27] So I think no matter — and some people might have said that was the beginnings of participatory research. Like those folks who said, well, we’re going to go into communities and we’re going to integrate and we’re going to go in and we’re going to be one with the community. And so I think the first thing we have to do is ask why: why are we doing this research? And then I think we always have to ask, are we the best situated to do this research? And if we’re not the best situated to do this research, then who is? And maybe we’re the best situated to do this research because we have the reources or we have the educational backing, but we shouldn’t be doing it by ourselves. So who needs to be on our team and who do we need to pay for that expertise in time?

[00:52:09] So I think whether or not you’re doing quantitative or qualitative, it could be bad, right? It can also be helpful. But you have to understand that, as I said before, data isn’t just numbers. Data isn’t just descriptions or coding. It’s about people, it’s about stories. And those of us who do research have to take our responsibilities well enough that we can’t just solve problems because we’ve determined their problems. We have to really be willing and we have to have a framing of what is the community? Who is the community? And I’m here to help, not necessarily do it on my own. And that process starts from the beginning. With research, too often, we like to go after and say, What do you think of my research? Is this helpful? And we have to start thinking about how we can start crafting those questions from the beginning with the people who are going to be most impacted.

Julian Agyeman: [00:52:59] Thank you, Michelle Meyer asks, How can we push institutions to offer more flexibility in funding? I’m thinking about nonprofits and putting money towards the actual solutions and allowing this to be driven by the people closest to the issues as opposed to being limited to what is written in the grants. And this is definitely also applicable for government, academia, etc.

Tamika Butler: [00:53:21] Yeah, this is a huge problem and I think this is one of the reasons a lot of people started talking about the nonprofit industrial complex. Because unfortunately, many NGOs or foundations have been instrumental in exacerbating some of these problems and making them worse. And so I think that we have to really start looking at the folks in power and who control those purse strings and start pushing them and advocating for them to think differently about how they fund. And that’s big picture. We need shifts and we need change.

[00:53:56] In the interim, what I hear from all of my professors that I admire and respect is you got to learn how to write the grant and you got to learn how to write the report, and you have to learn how in between those two processes, you actually do the work. And that’s different. You write the grant, you get the money, you write the report at the end and you say what you’ve done, but you have to learn how to do the work in the middle and the way that is most meaningful. And you have to cultivate sources of funding that have fewer strings. So you have to work on that now and you have to work on the change in the future.

Julian Agyeman: [00:54:33] Great. Thank you. One last question, and I think this is a really good question because I think it’s one that we all grapple with. So Georgia Gillan says, first of all, you’re amazing Tamika. So there you go. Secondly, she says, It strikes me that a lot of people in organizations who prioritize equity don’t actually understand or don’t appear to understand that an equity framework necessarily requires different people to be treated differently in order to meet them where they are. Do you agree with that? And then she says, I think the idea of fairness is entirely underpinned by meritocracy, a.k.a. white supremacy. Question: what are some steps you think we can take to reverse this mindset specifically through transit?

Tamika Butler: [00:55:17] Yeah, so I think something that we first have to realize is that we didn’t get to this place of inequity overnight. And so it’s going to take a lot of work to get there. There’s a new book out about reparations and it really focuses on reparations as a world-making project. And it’s amazing. You should all read it. I’m trying to look up the name of it: “Reconsidering Reparations” by Olúfẹ́mi O. Táíwò. And he talks about the way that if we’re going to change things, and it’s not just about reparations, right, but if we’re going to change things, we have to realize that there was a world-making process of imperialism, to shape the world in the powers of a certain way. And so it’s going to be a long fight to redistribute and to come up with a more equitable system. And he talks a lot about the environment and that’s why the environment is a place to focus.

[00:56:25] But one thing he says is we have to constantly be asking ourselves, what kind of ancestor do I want to be? Because my ancestors really fought for this? And did they give up just because it didn’t happen quickly? No, they just moved the fight forward. And I think sometimes that’s what’s so hard about equity work. I think you are absolutely right. It’s huge, right? It’s a mindset shift. It’s like people want to talk about fairness without acknowledging that nothing is fair now. They don’t want to acknowledge that people who have historically gotten the least have to get the most. And that means a different amount. And that you might get none at all. They want a win-win situation. It’s like, no, someone’s going to lose something, right? And that’s tough for people.

[00:57:08] But as a result, people get so stressed out are they just think this is work they can’t do. And too often they leave the work for the people of color, for the women. What I will say is, what kind of ancestor do you want to be? And you want to be one who’s just moving it forward. You want to be one who is figuring out how in your space you can make a little bit of shift, because that’s the only way we’re going to get this larger cultural change.

Julian Agyeman: [00:57:36] What kind of ancestor do you want to be? That’s a great place to leave this. Tamika, what a fantastic talk. I’m sure we could go on for longer. There’s more questions, but people have got to go to classes and we’ve got to go and do things. So can we give a fantastic round of applause for Tamika Butler, please?

Tamika Butler: [00:57:55] Thank you.

Julian Agyeman: [00:57:55] And on April the 20th, we have Kyle Whyte and Justin Schott, who are talking about the Energy Equity Project. Thanks, everybody. See you April 20th, Tamika. Keep doing fantastic work. Thank you.

Tamika Butler: [00:58:08] Thank you. Talk soon. Bye, folks.

Tom Llewellyn: [00:58:15] We hope you enjoyed this week’s lecture. You can access the video, transcript and graphic recordings of Stacey sentence presentation on Shareable.net. There’s a direct link in the show notes. As Julian mentioned, our next live online event is Wednesday, March 30th, when we’ll feature Tamika Butler’s lecture. Transportation and Equities. What’s data got to do with it? Click the link in the episode notes to register for a free ticket. And if you’re not available for the live event, you can always find the recording right here on the podcast.

[00:58:45] Cities@Tufts Lectures is produced by Tufts University and Sharable with support from the Kresge, Barr and Shift Foundations. Lectures are moderated by Professor Julian Agyeman and organized in partnership with research assistants Perri Sheinbaum and Caitlin McLennan. “Light Without Dark” by Cultivate Beats is our theme song. Robert Raymond is our audio editor. Zanetta Jones manages communications. Alison Huff manages operations. Anke Dregnet illustrated the graphic recording. Caitlin MacLennan created the original portrait of Tamika Butler, and the series is produced and hosted by me Tom Llewellyn. Please hit subscribe and leave a rating review wherever you get your podcasts and share it with others so this knowledge can reach people outside of our collective bubbles. That’s it for this week’s show. Here’s a final thought.

Tamika Butler: [00:59:30] Diversity, equity and inclusion are not interchangeable terms. To get to inclusion, you have to talk about power. You have to shift power. You have to shift control. And if you can’t get inclusion, then you’re never going to get to equity.