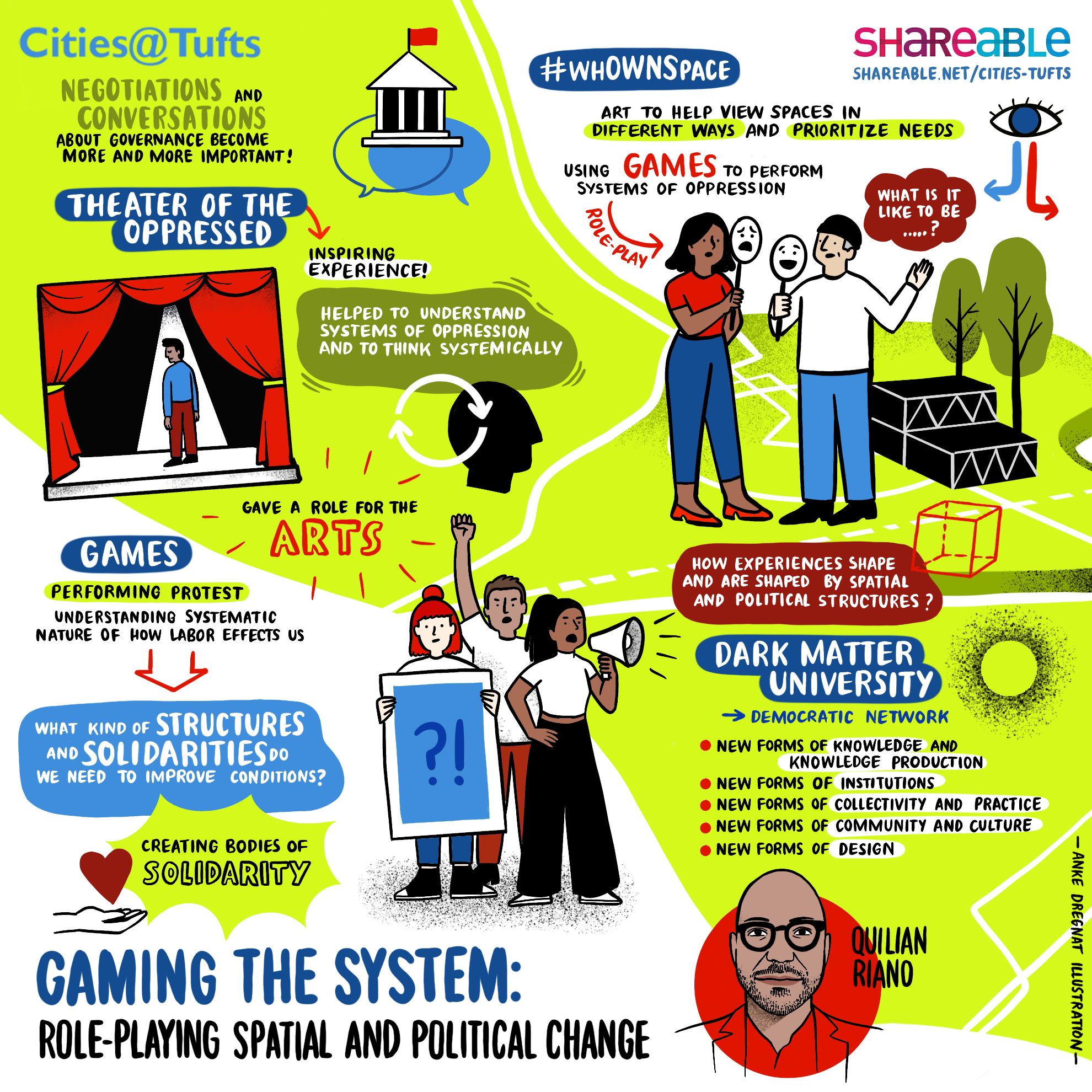

We have included the transcript, graphic recording, audio, and video from “Gaming the System: Role-playing Spatial and Political Change” presented by Quilian Riano on April 27, 2022.

About the presenter

Quilian Riano is an architectural and urban designer and the Assistant Dean of the Pratt School of Architecture in Brooklyn, New York. Prior to this, he served as the Associate Director of Kent State University’s Cleveland Urban Design Collaborative (CUDC), where he provided strategy and design coordination for the CUDC’s urban design, applied research, publication and academic activities. Quilian has worked in and with public institutions, such as New York City’s Department of Design and Construction as a lead design strategist and the National Park Service as an urban design consultant. Quilian is also the founder and lead designer of DSGN AGNC, a design studio exploring new forms of political design, processes and engagements through architecture, urbanism, landscapes and art. Quilian/DSGN AGNC’s design work has been featured at the Venice Biennale, Queens Museum of Art, Harvard University, The Storefront for Art and Architecture, The New Museum, the Center for Architecture, the Architectural League of New York, among others. For this work, Quilian has won awards from the Vilcek Foundation, the American Society of Landscape Architects, Harvard University, The Boston Society of Architects, and the University of Florida and received fellowships from the Design Trust for Public Space, Institute for Public Architecture, and the J. Max Bond Center for the Just City at CUNY, among others. Quilian has over a decade of teaching experience, having taught undergraduate and graduate studios in architecture, urban design, and transdisciplinary design at Harvard University, Columbia University, Carleton University, Parsons The New School of Design, The Pratt Institute, Syracuse University, Wentworth Institute of Technology, the City College of New York, and Kent State University. Quilian is an initiator and core member of Dark Matter University.

About the series

Shareable is partnering with Tufts University on this special series hosted by professor Julian Agyeman (Co-chair of Shareable’s Board) and Cities@Tufts. Initially designed for Tufts students, faculty, and alumni, the colloquium has been opened up to the public with the support of Shareable, and The Kresge Foundation.

Cities@Tufts Lectures explores the impact of urban planning on our communities and the opportunities to design for greater equity and justice.

Register to participate in future Cities@Tufts events here.

Listen to the Cities@Tufts Podcast (or on the app of your choice):

“Gaming the System: Role-playing Spatial and Political Change” Transcript

Quilian Riano: [00:00:07] One of my main interests has been that as we think about sharing, collectivising, creating more opportunities — negotiation and conversations about governance become more and more important. The ideas of collaboration, co-production, co-anything is not an end in itself, but it is a process and it’s an invitation for democratic processes.

Tom Llewellyn: [00:00:34] Can a Cooperative Cities framework address the unequal impact of automated traffic fines in Black and Brown communities? How can alternative land governance models help us respond to our climate challenge? And is there an equity measurement scheme that can bring clean energy programs and investments to front-line communities? These are just a few of the questions we’re exploring this season on Cities@Tufts lectures, a free live event and podcast series where we explore the impact of urban planning on our communities and the opportunities to design for greater equity and justice. I’m your host, Tom Llewellyn.

[00:01:05] Today on the show, we’re featuring Quilian Riano’s lecture “Gaming the System: role-playing spatial and political change.” In addition to this audio version, you can watch the video, check out the graphic recording and read the full transcript on shareable.net. And while you’re there, please take some time to get caught up on all of our past lectures and our ever-expanding library of stories, podcasts, how-to guides and other resources. And now here’s Professor Julian Agyeman, who will welcome you to the Cities@Tufts Spring Colloquium and introduce today’s lecturer.

Julian Agyeman: [00:01:48] Welcome to the Cities@Tufts colloquium, along with our partners Shareable, the Kresge Foundation and the Barr Foundation. I’m Professor Julian Agyeman and with my research assistants Perri Sheinbaum and Caitlin McLennan, we organize Cities@Tufts as a cross-disciplinary academic initiative, which recognizes Tufts University as a leader in urban studies, urban planning and sustainability issues. And I’d just like to say that this will be Perri Sheinbaum’s last — as a second-year student — last Cities@Tufts. And Perri, thank you so much for all the work you’ve done and Caitlin for carrying on into next year. We’d like to acknowledge that Tufts University’s Medford campus is located on colonized Wampanoag and Massachusetts traditional territory.

[00:02:35] Today we are delighted to welcome Quilian Riano. Quilian is assistant dean at the Pratt School of Architecture in Brooklyn, New York. And in that role he works across all four schools of the departments to help develop and amplify the research-driven spatial outcomes with real-world impact. Quilian is also the founder and lead designer of DSGN AGNC — I’m assuming that’s design agency — a design studio exploring new forms of political design processes and engagements through architecture, urbanism, landscapes and arts.

[00:03:10] Quilian and DSGN AGNC’s design work is featured at the Venice Biennale, the Queen’s Museum of Arts, Harvard University, the storefront for Art and Architecture, the New Museum, the Center for Architecture and the Architectural League of New York, among others. Quilian has over a decade of teaching experience and is an initiator and core member of Dark Matter University. He holds a bachelor’s in design from the University of Florida School of Architecture and a master’s of architecture from Harvard University’s Graduate School of Design. Quilian’s talk today is “Gaming the System: role-playing spatial and political change.” Quilian, a zoom-tastic welcome to the Cities@Tufts Colloquium.

Quilian Riano: [00:04:02] Thanks so much, Julian. Thanks so much to you, to Tufts to Shareable for inviting me to have a conversation with all of you. What I’m hoping to do over the next 20 minutes or so is I’m going to chat a little bit about some work and projects that I both have done, have been involved in as part of collectives and some of the ideas of where some of that work might be coming from. And also a little bit of conversations around how games and performance, etc., have made their way into different aspects of work and how one of my main interests has been that as we think about sharing collectivizing, creating more co-opportunities, negotiation and conversations about governance become more and more important. The ideas of collaboration, co-production code anything is not an end in itself, but it’s an invitation for democratic processes.

[00:05:07] So for me, it begins with [indistinct] — a left architecture school and I was interested in pursuing conversations around politics, but I wasn’t sure where to start. I was getting my education, although had not really chatted about some of these principles. For me, Theatre of the Oppressed was important because it gave tools for role-playing, for really trying to understand the systems of oppression and understanding that they’re not a one thing that can be solved, but rather a systems, away of thinking. It brought the body into into the conversation. My experience, my everyday experience of of oppression and systems is as important as many others and will allow me to then think about the systems. And so the body and the system are constantly at play. And it also gave a role for the arts. What is the role of the person, kind of the facilitator, the joker? And to me has always been helpful.

[00:06:19] The other work has mentioned [indistinct], a contemporary political theorist that basically has said that democracy has always been intention is in one word: a liberal democracy, liberal is trying to be a universalist, etc. And the other, democracy, is trying to draw a line among who belongs, who is in the system and who’s outside? And as this is facing a pluralistic moment, it’s having a hard time because a lot of the foundations of our democratic principles take into account an initial political subject, usually in our case, white men, landowning. And as that has been challenged, our institutions are having a hard time right now dealing with those changes and how can we have a fully pluralistic democracy?

[00:07:15] These two things have led me to thinking about how the idea of games. And when I mean here by games, I’m trying to find a word around how to talk about negotiation, how to talk about performance. And by performance I mean literally being in a room, working with other people. And at that time it can be performative, it can be similar to Theater of the Oppressed, role-playing or something like that, or at the very thing that we’re doing, the negotiations and governance is as a kind of performance. You know, at times I have gone away from the word games. I come back to it because it can be misunderstood that it’s about playfully playing ping pong at the office or something. And that’s not what I mean.

[00:07:58] So I’m going to start by sharing some of the work. I’m going to start with the Architecture Lobby. It’s an organization, a collective that I was a part of for many years. I have taken a step back, but it is something — it is work that I did for close to ten years that’s very close to my heart. And so with Peggy Deamer, the founder, and the great national and international teams that have come to organize under that organization. For anyone that doesn’t know the Architecture Lobby it’s an organization that really advocates for architects as workers, that is trying to bring conversations around labor into a larger architectural community.

[00:08:43] I wanted to begin because performance — performing a protest, it has been an important part of the lobby from the beginning, going to a Chicago convention, I think it was 2012, to 10 years ago, and showing that we are precarious workers. And we brought that as a way of working. And then that idea performance of Theatre of the Oppressed being used as a way to think about our everyday experience within labor. So during the Chicago Biennial, and I honestly forgot how many years ago, we put together with a great team of people, many, many people working on scripts, working, bringing their own experiences to create scenes, one for each of the manifesto points, and to go through that idea of trying to understand the systematic nature of how labor affects us and what kind of organizations, what kind of structures, what kind of solidarities do we need to be able to change some of those conditions? Again, staying away from solutionist approaches, but rather creating bodies of solidarity. It’s on YouTube, it’s called “Reworking Architecture.” And I’m going to invite you all to take a look at that. I won’t post the link because then you won’t pay attention to me anymore, but I will invite you to then.

[00:10:11] Then the same group— I think that it has two broad, large efforts. One is around unionization and conversations around how to bring unions into architecture, the other one around cooperation, cooperative networks, understanding that a lot of architects are also kind of small practitioners, etc. A group of us, as you can see here, [indistinct] wrote the research and wrote pieces on how to begin to bring those small practices together into a cooperative network that both would allow those firms and small practitioners to share resources, but also then to begin to participate in the larger network of cooperatives and collectives that can affect community. So we’re looking at also partnering with people already working and doing this kind of work.

[00:11:10] So that’s a little bit on the Architecture Lobby. And out of that, what I wanted to share is that idea that starting with performance, moving to that kind of almost Theatre of the Oppressed image theatre is sections in which things are identified, then identified and beginning to create a collectivity out of that. And then I’m going to chat a little bit about a couple other projects and things. My first experience with collectives was Who Owns Space? It was a conversation around the increasing of privatization of public space in our cities and what that could mean. This one was a collective with artists, urban planners, lawyers. And we did everything from creating these kind of vignettes about the way that public space rules were being broken to tours of privately owned public spaces. And this work led to a commission work with the Queens Museum of Art, not just the Queens Museum, in Corona. My background right now is Corona Plaza in the neighborhood of North Corona in Queens, heavily immigrant neighborhood and mostly Latinx, Mexican-American, Ecuadorian-American, Dominican-American, Colombian-American.

Quilian Riano: [00:12:26] And a new plaza was going in here and the conversation was about how to create a process for a new kind of sharing of space and new engagement. One of the things that I share with the Queens Museum is that I didn’t really want to design the Plaza, but I didn’t see that as the project here. But more about designing the engagement processes that would have conversations, that would leave even behind groups of people that can advocate and have conversations around how public space is used. So we started with this, the design agency team and I created this series of signs. We call them “lo fi augmented reality” that allowed people to see the plaza in different ways through plexiglass and allow us to have conversations going back to the themes around privatization, public and uses in Spanish and English. And then out of that we identified five major items that people were talking about: social services, green spaces, mobility, local economies and community programming.

[00:13:37] We decided to turn this — and at that time I was actually also teaching and working embedded in Colombia with an actual Theater of the Oppressed group that had been doing urban planning. And so these questions were on my mind. We decided to create a game, a negotiation game. Each of these five items got three pieces, and so 15 total, and we created a 12 piece board. And then through prompts, the idea was to get people to have conversations — a game without winner or loser or no real aim except to have the conversation itself. So we — this is what that looked like. This is the plaza one winter, I think, in 2011 and 2012. And people stood for hours in the snow, playing the game and talking about, with each move, talking about what they meant — the fear of what would happen to the tamale lady that stands there, the fear of more banks and more and cellphone stores coming in and replacing the retail activities that actually give a lot of the immigrants here their first jobs, etc..And then we gave to the Queens Museum, the Department of Transportation, a series of notes from these meetings.

[00:15:06] But then I kept wondering, similarly to the public space conversation about the systems by which these public spaces are maintained, managed and both what they could mean for this conversation between privatization, public goods, etc.. And one of the things that was happening while right after I finished my project with the museum is that the people that were managing the plaza as per the plaza program tools decided to no longer do that. So in order to maintain the Plaza, a large business improvement district was proposed in Jackson Heights. It was to expand the existing one in 82nd Street, Little Columbia way. And I was interested in looking at a piece of policy as a design, understanding that it’s a complex piece of policy and that it has both social and spatial outcomes and to find its history the way it has been used and the potentials for a community like this. And so I put together a studio called Urban Embodiments at Parsons in the Masters of Design and Urban Ecologies.

[00:16:23] A great group of students that worked on this. We started by doing research into three major themes: the social infrastructures, meaning that the physical spaces, the political economies, things like business improvement districts and other rules that govern that infrastructure. And then the communal process, how people’s everyday experiences both shape and are shaped by the two, the political economies and the social infrastructures. And out of that and doing the research, four teams were reconfigured and created. I’m going to show you the work from two of the teams, the negotiating space for negotiation and the [indistinct] agenda engine. The negotiating space for negotiation seems more important today than even back then. And because of COVID, there’s a lot more happening in front of businesses and the street eateries. These students use the beginnings of those rules, the rules that the Department of Transportation had in order to create a political economy that would be new, that would be basically by using this as an excuse to create a new micro-political unit of tenants, street vendors, people, other kinds of businesses that were in large businesses, to maintain and create something similar to what a business improvement district does.

[00:17:52] And for people that don’t know, a business improvement district does basically three things: create uniform signage or some sort of identity for an area, picks up trash more often than the city will, and creates a sense of security — whether that’s through things like cameras or security guards. And in the research we found that — you have to buy into that, these things are all good, but the business improvement districts are generally successful in doing those three things. But the questions are, are those three things good? And the question is how democratic it is? Because what happens is that a nonprofit often with a board, with some of the people that are taxed here, some of the larger landowners especially, can dictate things in public space in ways that that cannot be done otherwise. So if the existing bid here didn’t allow for, at the time when we’re doing this research, street vending. And there was a lot of concern that the expanded business improvement district wouldn’t allow that either. And so that’s an example of — so, if it does those three things, these three questions, how can we do that in a different, more collective way?

[00:19:08] The second group — the [indistinct] Agenda Engine, basically took a page from the original monopoly and allowed people to play the way a business improvement district, what it is, how it works and then as it exists now with the relative power dynamics of the place. So they created personas for everything from large landowners, developers, to street vendors. And then they would play at once the way that a bid works and begin to see what those dynamics would be. And they would play one `one more time trying to re-imagine how to do the same things that a business improvement district would do in other ways. So this is what the students created. This is a group of street vendors working on this project and basically playing the game. I brought a group of students from Carleton University in Ottawa to actually work in Queens out of the Queens Pride House and a group, without me sharing the previous team’s game, decided to create a game. In this case, the game would be to create a spatial dynamics bringing in politics. For example, if the councilwoman was supporting you, what would you be able to do if you were working with one of the major nonprofits? So, creating a scenario of constituency and political bodies buildings in order to shape and reshape space. I’m putting some of the players, for example, there’s a school nearby. What can be done to shift space for those children? That kind of question.

Quilian Riano: [00:20:50] So that’s the Corona work. Again, it began with who owns space, questioning public space, then moving into an actual space with the immigrant community and really working on negotiations and having conversations and then shifting to what that means at a larger urban scale and looking at policies like the Business Improvement District as a more specific kind of design, that the policies themselves are designed to have specific outcomes and then they lead to social and spatial outcomes.

[00:21:25] The last thing I’ll say about this is that for anyone that might not know them, one of the things that I found most interesting is that basically it was a way to compete with malls. So one of — they start in Toronto — and one of the, as white flight took hold of cities. And it was basically a way to make people feel in cities more like they would feel in a mall, something I’ve always found kind of interesting. And so I’m going to share a couple of other ways in which then games have been used. This is a project, a small little project that I made for Dallas. It was for an arts conference about the future of the southwestern city. It’s one of those in which they give you almost no money, and then they want you to build a little pavilion, something for this arts conference. So what I decided to create was a quick and easily manufactured and placed a sandbox in which the children or anyone that uses it would negotiate land and water. So all these yellow wooden sticks here, you can actually go into the sandbox and either create your own little corner of it or you can share more space. And the more space you share than there’s new catcher in the back, you could use more of the water. So it was a hopefully a fun way to think about the kind of resources and that kind of dynamic around sharing and negotiation.

[00:22:50] Another one was in Nicaragua, where in a collaboration with studio [indistinct] landscape artist [indistinct] and the studios, he was teaching at [indistinct] and also started us as [indistinct] — so using all this to think about how to develop a housing project in Nicaragua in a site that did not have a great survey. So we don’t know where the trees are, where we had to have a light touch and also create opportunities here for there not to be a masterplan, but rather what we created was something that I would call a set of rules, again, a game-like set of rules that people on the ground can interpret and an all around, using the trees. So it began by identifying where the trees are, identifying a middle zone for things like infrastructure, water for pathways, and then allowing where the trees are to be. The main reason why you would move and where you would place the house. The house itself then rethought from what was being built, which was kind of these CMU boxes, into more open structures that would allow more light and air to come in and would also allow the house to grow over time.

[00:22:50] So now I’m going to go into the conversation around Dark Matter university. The important thing here to note is that I was in Ohio doing work and research around cooperatives, collectives, very interesting things like the Evergreen Cooperatives — Cleveland owns a community-driven, mostly led by people of color group, that was creating new models of collective ownership and spatial creation through that. And then after the murder of George Floyd and as the pandemic was beginning, the conversations as they began to hit architecture, made a group of us, BIPOC design educators, talk about some of the things that our own fields needed to start doing. And so we came together and a group of us, about, I think the number is anywhere between 12 to 20-something created Dark Matter University, a BIPOC-led a collective that is trying to reimagine education. It’s democratic in nature, and what we’re trying to create is new forms of knowledge and knowledge protection, new forms of institution empower, collectivity and practice, community and culture, as well as new forms of design.

[00:25:29] It started with Tuskegee University, five of us teaching a course, and [indistinct] and myself working with incoming undergraduate students. And it was great sharing basically our paths. And all of us both have many things in common, but we also have slightly different paths that we’ve taken within the design world, created a constellation of courses, both applied and taught. So I’m going to share with you a little bit of one of the first studios that was titled as part of Dark Matter University between landscape architect [indistinct] and myself. It was called Cooperative Futures, and the studio was done as, again, the idea of Dark Matter University was to allow institutions to reimagine even how classes are taught. So in this case, it was a relationship between Kent State University, Carleton University in Ottawa again — different group of people, it actually was interesting. [indistinct], who taught another Allied studio, mini studio, called for with — an individual practice towards collective expression that was really incredible, looking at African-American arts, culture expressions and finding urbanism and spatial outcomes out of that. And then the studio we had, which was more around — if all these things are really happening in Northeast Ohio, what is the spatial expression of collectivity in some experiments around that? And I’ll share that. And some of the community partners where Cleveland owns, Third Space Action Lab, 12 Literary Arts and even the Community Development Corporation of Midtown participated. And so what it allows us is to have a constellation of two studios happening at Kent State and Ottawa and Carlton with the same theme, then two studios within Carlton, then a group of community partners all working with us together. It was really a fun experience.

[00:27:41] We’re looking at the community of [indistinct] that sits between downtown Cleveland and the Cleveland Clinic and Case Western University. So two enclaves with incredible wealth in Northeast Ohio with community, mostly African-American communities in the middle, that have been redlined and systematically disinvested on for decades. So what we did with them is create a system and the Kent State studio I was teaching by myself, but used the same systems, in which it would allow us to look at the folks already making change in the ground, all of them interested in collectivity in one way or another, and begin to design for people on the ground with the body. So taking that idea, then they would move to body. So to design for two or three bodies, then to begin to aggregate that into maybe a building, a landscape or chunk of urbanism and then into an urban context. So body, bodies, aggregations and connections. And then at each stage the students had to negotiate with other groups. We created — I forget if it was four or five groups.

[00:28:52] So for example, at the body stage, let’s say I was designing almost a piece of furniture — a spatial piece of furniture for one person. I would have to talk to another group that had done the same project, talk about and think about the person they were doing it, or the agglomeration, the kind of persona that they had been building for. And I had to consider what they had been doing. The person’s story, the spatial idea and incorporate and make changes. Mutations. So you would make, you would negotiate, you would mutate your body scale piece and then you would scale up to the next scale with that mutation in mind. What that led to is that everyone’s — we were working collectively — and everyone was working almost with ideas and thoughts from every other group. But you were still working on your project. So it was a way to create, to almost make visible some of the themes you may have seen up to now around negotiation, mutation, bodies, political bodies, everything from this scale to larger scales. And that the back and forth between those bodies.

[00:30:06] So what that led to was some interesting work. For example, this group here looked at the 12 literary arts and it’s a group that within [indistinct] and the surrounding communities that brings writers into residencies. So how would their needs match, for example, the needs of children in the community? And design spaces for housing for the community, residencies, and play — all at the same time. So beginning to create almost hybrid structures that are very grounded of what’s already happening and begin to provide more. And one of my potentially favorite cases of this group was really taken by the story of [indistinct], a ballet dancer who is also does community-driven processes and was working for urban design, urban planning processes, and they were taken by her process that includes performance and includes — not the only thing, but it does include that — to begin to think about what the work she was doing with the especially young people in the community. And [indistinct] created what they call the [indistinct], a series of spatial strategies that could be applied by the communities themselves, tested out, and if they prove to be something that people want, then amplified on. They use the space paradigm. [indistinct], a local technologist and he’s also part of Cleveland Owns, he owns a series of public spaces in this area and they also were interested in working with someone like Mansfield Frazier, a gentleman that sadly passed away about a year ago, who owns a veneer in [indistinct]. So he’s literally growing grapes and blinds in this community. As well as looking at the smaller space. So not only for new spaces, for existing spaces to amplify the connections and community relationships.

[00:32:08] With that, I’m going to end and there’s always more. And I left a lot on the table, but that was all the time I have and I want to get into some conversations. Thank you.

Julian Agyeman: [00:32:19] Well, thanks so much, Quilian. This is a really interesting presentation on so many levels. We don’t get to engage as urban planning, environmental policy and planning people perhaps as much as we would like to with architects. And so your world and our world, of course, are very close. But maybe we should explore the places in between a little bit more. Can I start? We’ve got several questions, but can I start? You use the word space probably more than you did the word place — to an architect like yourself, how do you differentiate place and space?

Quilian Riano: [00:32:55] Interesting question. Julian. Yeah, and I think that shows my training. For me, it’s funny because it’s the first time that has ever been asked of me and given the kind of work and the kind of places where I present it actually is a little bit odd that it has never even been asked before. But as I think about it, I feel like I use the word basically interchangeably. It maybe is a way to both understand that the built environment shapes and is shaped by people. And that is the heart of what I use the word spatial as, but perhaps my education and being asked at every review. “where’s the space in this?” has invaded my, my language. But really what I mean when I say that is how the built environment is shaped and how that shapes both communities and policies. And they really what I’m interested in is the interaction between those three things.

Julian Agyeman: [00:34:00] Thank you. And I think segueing from that, Roberto Morales asks, What do you call this practice in Spanish?

Quilian Riano: [00:34:09] Interesting question as well. I mean, I’m not sure if you’re asking me literally to translate it — the disclosure is that my Spanish is good enough to like chat. I am Colombian. I was born in Bogota, Colombia. I grew up in Miami. Have lived all over the US, including New Mexico, South Dakota, Boston, New York for a long time. Cleveland. I actually am not 100% sure how to call this. I can share this with you. And I think it’s a really interesting question. Roberto, and you probably know this, given what I see of your flag here, is that there are many collectivos that are happening everywhere from Chile to Puerto Rico. You know, I’ve known some of them. In Venice, I was doing a project one time around immigration in Venice and a collectivo from Puerto Rico came out. The practice I’m not sure it has a name in itself because but it is interesting that it is typically a mixture. And as is mine, I am maybe a North American version of this. I’m obviously not the only one, but I even don’t know what to call it my own practice, that is between arts, architecture, urbanism and just whatever.

[00:35:30] And even the language that I use when I go into communities changes. If I feel like calling myself an artist opens up certain opportunities, I do. If I find that my training as an architect is helpful to mention, or if my interest and experience and teaching career in urbanism is important. And I find that these practices are care a little bit less about the name. And I have studied them both in Europe, Latin America and North America. North America tends to be a little bit harder just because collectivity in North America tends to be a little bit harder to pull off — everything from student debt to prices to the way nonprofit things work, in tenure. There are many systems that actually try to enforce individuality versus collectivity. But in the places that I have studied, and also a little bit in Southeast Asia, in East Asia, found a little bit less. But I’m sure they exist and I’m just not aware. As well in Africa I do know a couple of collectives, but in everywhere I think that people just use the word collectivos, collectives, and they are trying to maybe focus on the larger issues of being maybe change agents and less on kind of describing what they do. And they just use whatever tools they have, they work with the local communities, etc..

Julian Agyeman: [00:37:06] Roberto, would you like to follow up on that?

Roberto: [00:37:11] I would love to, I guess as a sort of gamification of engagement, that way of doing it. I’ve heard of it before. I’ve seen an example when I was doing my planning masters and I would love to look into it more because I’ve seen that it’s very successful in getting people to understand difficult concepts. And to participate. Right. So what would I Google?

Quilian Riano: [00:37:43] I’m going to share with you what I’ve done, which is I will look at Theater of the Oppressed, because I think that what Theater of the Oppressed does that are other gaming platforms doesn’t is that doesn’t leave politics behind, doesn’t leave systems behind. It was created specifically to decolonialize, before that was even a word or a little bit of what has become a buzzword at this point. And I think that perhaps looking at an analogous research, the places, other places that are doing it. And again, I would say the performance might be a good place. There’s also things like serious games. I know even the UN and other people use that word, the idea of serious games as a way of doing it. But for me I’ve found it more productive for me personally to go through that lens, not calling myself a performer, but rather invite people that do it, learn from and work with.

Julian Agyeman: [00:38:38] Are you an animator, Quilian?

Quilian Riano: [00:38:42] What does that mean?

Julian Agyeman: [00:38:45] And are you an animator? I saw somewhere in Toronto that the city council at some stage, about ten or 15 years ago, employed some people as community animators. And I like that concept. People who animate.

Quilian Riano: [00:38:59] No, now that you mention it. Yeah. And it sounds similar to what happened in Bogota, where even at times like the famous thing of clowns to make fun of your driving, that kind of thing. But I don’t know. I mean, I haven’t really ever thought about it quite that way. I mostly feel like my practice has been about asking questions and, yeah. I don’t know. And I’m going to share this with you. This is one quick thought, and it may or may not answer the question, as I feel like what I have tried to do is, that as you come in and you see what the dynamics that are happening in working class communities that are usually in the US, that is, I’m meaning communities of color, immigrant communities, etc., that there is always this idea that change is inevitable, right? That change is just going to come. So for me, the question has been one about asking, okay, I, as an immigrant, I’m changing to a system, right? Yet the agency for change is not equal across the board. The way that the Upper East Side changes is very different than the way that Bed-Stuy changes, right? So what are the reasons for that? What are the policies? And then trying to create structures by which some of that change can be more driven by the communities that are affected by it, not to stop it, not to anything, but rather to ask the questions that would allow those groups to be in the driver’s seat. Or at least something like that. And not to say that it’s been successful, etc., but that is the question.

Julian Agyeman: [00:40:49] Great. Thank you. We’ve got a question from [indistinct]. What do you think are the benefits of incorporating play into our fields and generally into our lives and fields? I think that means professional fields.

Quilian Riano: [00:41:05] I think it’s very important. I think play can do a couple of things. It can sometimes hide more serious conversations, right? It can bring them up and make them less threatening. So I think it’s very important. But again, I think it’s important to not forget, as you do that, to then bring the larger questions, the politics, the real kind of conversations behind. When it becomes play for play sake, I sometimes wonder if it then becomes a tool to soften a change that may be uncontrollable change. So what happens when there’s someone that wants to change a community, puts up luxury condos, and that’s going to displace a whole bunch of people. When they begin to put out the big chess games and the things that look fun and kind of informal, etc., they that is a way of using play. And the way that sometimes in now in labor you see it to the ping pong tables, etc.. Yes. And one way that can be great ways to bring wellness in other ways is to like disguise that the blurring of work and life can end up becoming a labor issue, right?

[00:42:30] So I just want to complicate the idea of play, not to make it seem like it’s an end in itself, but rather that play might allow both to be able to bring people along — it also brings young people along, which I think is incredibly important. And I think often like providing things that are playful will bring often young people and their parents too. And in that, you might be able to have a bigger conversation that you wouldn’t have otherwise. The last thing I’ll mention around plays, that play brings the possibility of something potentially unusual, weird. Like that game in Corona that by the very kind of, I don’t know, I don’t think everyone knew exactly what to make of it, but that allowed them to open up possibilities and conversations that were not typical.

Julian Agyeman: [00:43:29] Great, thanks. I’m just thinking about the words play, performance. These are words that progressive architects are using a lot. And are we using them enough, I wonder, in urban planning. The pursuit of joy through play and performance, the sidewalk ballet, we’ve had all of these ideas. I wonder how much we are really adopting those into sort of planning, policy and practice. That’s just me musing. I want to ask a couple of questions about Dark Matter University. I mean, Quilian, this is where you and I sort of came together and I just think it’s a fantastic concept. Can you tell us a little bit more about the potential for growth of this idea? Because, if you think about it, I thought Dark Matter University, where is it? Where is it located? And of course, it isn’t located — it is a very fluid idea. What’s the vision amongst the organizing group for where this goes?

Quilian Riano: [00:44:27] So, thank you so much for asking about it because it’s a group, a space against space, but a community that I’m very proud to be a part of. I think that when we started, in a funny way, we started we moved very quickly and within months of like coming together and giving it a name, we were kind of in that first course in Tuskegee. A few months later, we had multiple courses and multiple places. One of the great things that has been collectively Creative’s Design Justice Fundamentals course that has been taught in multiple schools, and usually, if not always, we ask that, the collective asks, that it’s taught of two places at the same time together. So we had Utah and Florida A&M and all the students would come together virtually and to have that conversation and to work. So that led to some great experiments, both within DMU, allied to the DMU, slightly out of it, but still part of it, between [indistinct] teaching maybe at Howard and Yale or different things like that. Things that now have shifted policies at those schools. So that happened very kind of quickly and there was lots of energy.

[00:46:00] The reality is that both some of that can continue. And one of the advantages for us was that virtual teaching and that moment really allowed us to be very flexible and to do some of these things and to do it well. Now, as schools are beginning to go more and more in-person, the question is going to be how much of this we can continue and how much we can amplify on. The question on the table for us always is going to be how much do we work within the existing institutions? How much do we create new ones?` So that we create our own summer school? And as well, I mean, something that personally for me is important and that we also talk about is how to respond that after we started this, multiple places? Some of this kind of education illegal? Or very close to illegal. And what is our responsibility within that? And then how can we work within our collective or with other collectives to respond to things like that?

[00:47:08] One of the beautiful things about is that is flexible, that there’s so many of us that we have different ideas and performance also brings some interesting concepts. Like, for example, in the Architecture Lobby, very early on, we started using the both and so bringing in kind of improv language into our community organizing. The designers protest group, I love that they have this idea around bias towards action and that there’s enough people and enough things going on that we can have multiple things and experiments going. And some of the things will continue. Some of them will not. And there was a course that was taught by a group of folks with [indistinct], working with community members from New York City Housing Authority (NYCHA). And that has spinned into other courses and into other ways of working. So for us, I think that the future is about amplifying and kind of sharpening the things that we’ve already done and looking at possibilities is also with other groups outside of academia, how to bring that also and to work more closely with folks affected with these changes. And then the larger question of what to do as potentially the national environment gets hostile towards these ideas.

Julian Agyeman: [00:48:42] Just being aware of the time and looking for a last question. You mentioned institutions and we desperately — I think all of our universities are looking at the institution itself in the light of all of the conflicts that we’re facing, certainly here in the US. And I’m thinking, do you only work with like-minded institutions? You get requested to come into certainly like-minded — what if Brigham Young University asked you to do some work with them? I mean, I can think of certain institutions that are more needy of your work, but that you’re not as likely to be invited into them. What’s your strategy in terms of working across conflict, if you like? I can imagine some places, yes, would not like the messages that you’re bringing, but would you still work in those institutions?

Quilian Riano: [00:49:37] That is the kind of thing that really is a collective question. I think that any institution would have to be willing to work with us and that at times it’s good for the collective to push back on an institution and at times change the way it works. Again, not all institutions want to work in that collective way that we’ve been asking the two institutions to work together, maybe share faculty, share resources. Yet when they do, they’ve really enjoyed it. I personally would agree with you, Julian, that I think that at times what we need to do is we need to go to a place — this is the way I see it. As you can see, my work has been similarly to the inside and outside institutions at times have literally been in the very activist edge of it where I’ve sued government agencies and I worked within a government agency. And the question is, both, for me is, how to affect the systems that are going to affect most people, and those tend to be existing institutions. Often state schools, often in places that may not be welcome. So for me personally, it is important that we have these conversations and that we are going there. But then what I think cannot happen is for us to compromise the kind of work — because it’s very compromise, it basically it’s the status quo. Like people are not willing to talk about race and built environment. People are not willing to talk about these subjectivities, new models of connectivity, etc.. So that’s just the status quo and come to the status quo that would be difficult for this kind of organization.

Quilian Riano: [00:51:30] So, I think the larger question and the one that I think is really interesting for all the organizing to have done, for all the tools, is that I think in this moment, especially, it’s important to hold institutions accountable, to change them where we can. Because similarly to where I began with [indistinct] and these conversations about our government being the biggest institution we’re a part of, but it has that subjectivity, right? What I personally have come to call, the implied subjectivity of architecture school. Of planning school, of all these things is the same. I see a similar process as large democracies. It was created for a small group of people. It has expanded. It’s doesn’t really know how to respond to it, yet it’s important that something happens, because if not, those spaces are not going to change and they’re not going to be welcoming the people and the ideas and the ways of thinking that would bring about further change. And the change is right here, I mean, the demographic shifts, they’re here. They’ve been here in many cases forever. There’s always been people of color in the U.S., that’s not something new. However, the demand for a pluralistic democracy is something that is more contemporary. And the way that we’re describing it — pluralistic doesn’t mean that you become like this. Doesn’t mean that people come in and begin to fit the subjectivity that the institution demands of them, but rather that the institution can accommodate multiple overlapping, at times, hopefully productively conflicting subjectivities.

Julian Agyeman: [00:53:26] Quilian, on that, I’ve got plenty more questions, but thank you for bringing such thoughtfulness to our final Cities@Tufts Virtual Colloquium for this spring semester. Can we give a round of UEP applause to Quilian, please?

Quilian Riano: [00:53:42] Thank you all so much.

Tom Llewellyn: [00:54:06] We hope you enjoyed this week’s lecture. You can access the video, transcript, and graphic recordings of Quilian Riano’s presentation on Shareable.net, there’s a direct link in the show notes. As Julian mentioned, this was our final event of the semester. We’d like to thank all of our speakers, everyone who joined us live, and of course, podcast listeners like you. Stay subscribed so you don’t miss out on the bonus content we’ll be releasing between now and the next CitiesTufts Colloquium this fall.

[00:54:32] Cities@Tufts Lectures is produced by Tufts University and Sharable with support from the Kresge, Barr and Shift Foundations. Lectures are moderated by Professor Julian Agyeman and organized in partnership with research assistants Perri Sheinbaum and Caitlin McLennan. “Light Without Dark” by Cultivate Beats is our theme song. Robert Raymond is our audio editor. Zanetta Jones manages communications, Alison Huff manages operations, Anke Dregnet illustrated the graphic recording, Caitlin MacLennan created the original portrait of Quilian Riano, and the series is produced and hosted by me. Tom Llewellyn. Please hit subscribe, leave a rating and review wherever you get your podcasts, and share it with others so this knowledge can reach people outside of our collective bubbles. That’s it for this week’s show. Here’s a final thought:

Quilian Riano: [00:55:15] What we’re tr†ying to create is new forms of knowledge and knowledge protection, new forms of institutions and power, collectivity and practice, community and culture, as well as new forms of design.