Rural electricity and telephone co-ops are one of the great sharing success stories in American history – largely due to coordination by the federal government. In 1934, only 11% of farmers had electricity compared to 90% in Europe. Private electric companies refused to serve many rural customers or price gouged them when they did. The Rural Electrification Administration (REA) was formed in 1935 to fix the problem by providing technical assistance and loans to electric cooperatives. Less than 20 years later, practically all farms had power due largely to electric co-ops.

The REA was such a success that the same strategy was used in the 40s to make telephone service available in all rural areas. The Rural Telephone Administration matched the success of the REA. To this day, 1.2 milllion rural residents are members of a telephone co-op.

The US government’s success in boosting rural economies through cooperative development is a largely forgotten story that couldn’t be more relevant today. For instance, in creating jobs.

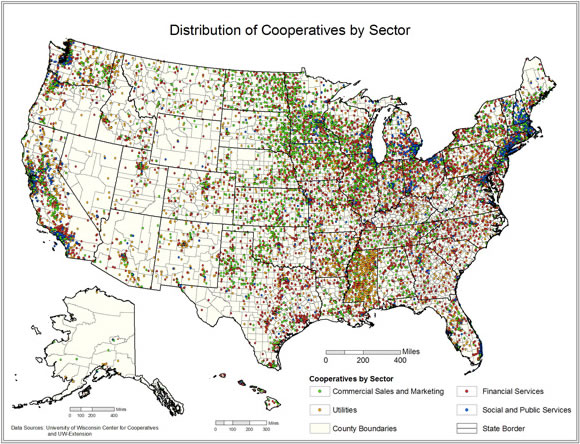

Member owned cooperatives are a proven economic development strategy the world over, and were recognized as such by the United Nations which declared 2012 The International Year of the Cooperative. The democratic ownership and management of cooperatives creates stable enterprises and jobs. Yet, none of the $20 billion in loan programs available to rural cooperatives are available to urban ones. This is despite the fact that 80 percent of Americans now live in cities, with some of the highest poverty rates in the country.

Last year, when cooperative groups were visiting Congressional offices on the Hill in support of USDA programs, Congressman Chaka Fattah, who represents an urban district in Philadelphia, asked why co-ops in urban America didn’t have similiar support. A year later, a bill developed by Fattah and cooperative groups – the National Cooperative Development Act – aims to bring technical assistance, revolving loans, and startup capital to coops in cities across America, recognizing that coops are a vital and long-term economic development model.

HR 3677 would set up an organization within the Housing and Urban Development Administration and administered by a separate non-profit to implement the kinds of support needed by coops. The bill would also set up a revolving loan fund for machinery, buildings, and the other startup costs. Currently with 13 co-sponsors, the bill will be reintroduced in 2013 in the new session by Congressman Fattah, with more bipartisan support, according to his office.

“The fact that cooperatives are seeing a resurgence in urban areas shows the strength, diversity, and staying power of the movement. I really believe that cooperatives are an excellent means for economic development and community enrichment,” said Congressman Fattah, whose family shops at the Weaver’s Way grocery co-op in Northwest Philadelphia and sees the co-op model as a solution to urban food deserts, among other problems.

Compared to the rest of the federal budget and rural co-op support, the program is tiny – $25 million over five years. But it’s a start, and would be official recognition that coops are still an excellent way to create strong local economies and local jobs in the era of globalization.

A lot of the grants would be regranted through the cooperative development centers that work as hubs, knitting together state-wide networks.

A “Grow Your Own Food Co-op” sponsored by the Northwest Cooperative Development Center.

One critical thing that the Rural Utilities Service (part of the US Department of Agriculture’s rural development area) does is direct co-ops through the maze of low-interest loans and grants not specifically directed at co-ops, but for which co-ops are eligible: programs to fund telemedicine, biorefineries, programs for people of color and women, grants for high energy costs, and a lot more. Those programs totaled $21 billion last year for rural America, capital that in cities is often very hard to come by but does exist in other nooks and crannies of the federal budget.

“A really big problem for growing cooperatives is that they often have difficulty expanding their operations because they cannot raise sufficient capital. Either because they can’t raise the funds from their existing members or they may not be able to get loans from organizations that don’t quite understand the cooperative business model,” said Congressman Fattah.

“A second key problem is lack of knowledge… Many new cooperatives are filled with people who have the energy and enthusiasm to start the cooperative and get it moving, but they may not have the specialized knowledge that is needed to ensure that the co-op continues operations long after that initial burst of enthusiasm runs out.”

Peter Frank is the Advocacy Manager for Cooperation Works, the national network of co-op development centers. He is working on the national campaign for HR 3677, getting cooperators in various states to make visits to elected officials.

Frank is also in year five of organizing a food co-op in the Fishtown neighborhood of Philadelphia. He and a group of organizers have recruited 270 members, and are aiming for 750 members by the time their business opens. The idea is indeed catching on in Philadelphia, with its tight-knit neighborhoods and participatory culture: there are currently seven food co-ops starting up in various neighborhoods.

“When you set up a co-op, you’re not just setting up a business, you are setting up a democratic organization to run that business,” said Frank. Accounting is different. Membership is new. The bylaws are different. You don’t dazzle a couple of investors – you build support from the community, member by member, worker-owner by worker-owner.

A startup at work, co-op style. Photo from Cooperation Works.

From looking at the success of co-ops in rural America, you can see a pattern of latticework: members of a purchasing co-op are often members of another co-op to take their product to market, a mutually reinforcing system of that deepens relationships and builds community resilience. In the recent economic downturn and this summer’s drought, the number of cooperatives had shrunk while co-op employment went up; the USDA speculated that a number of co-ops had merged rather than close.

It’s very similiar to the 50-year experience of the largest system of cooperatives in the world, Mondragon, 256 interlinked companies with over 83,000 employees, operating in Spain under the slogan “Humanity at Work.” In the recent documentary Shift Change, Mondragon is shown as successful precisely because humanistic business principles are simply better for business, the community, and for longevity.

As American cities explore alternative economic models amidst recession, co-ops are emerging as a smart choice. Telephone co-ops plunged ahead for 20 years before the federal government got involved. Hopefully, this time, it won’t take so long. The New York City Council this year funded Brooklyn’s Center for Family Life to train two community organizations in co-op development. They’ve already help start six co-ops so far, all with a focus on immigrant communities. But federal funding is not nearly what cities need to kickstart an urban co-op movement.

That’s a shame. Compared to the default method of economic development – giving tax breaks to lure out-of-town corporations – co-ops may be one of the best ways to bring quality jobs back to American cities.

##

Want to start a co-op? See Mira Luna’s article on How to Start a Worker Coop.