Thanksgiving can be a difficult time. Like many, I’m ambivalent about it due to its troublesome political implications and the roiling emotions it evokes. The holidays could be a contentious time in our family, and once I grew up I avoided celebrating for years, escaping to a bar in lieu of the inevitable annual re-airing of grievances. But in recent years, my immediate biological family has nearly dissolved: my sister passed away eight years ago. My grandmother, who lived with us throughout my childhood and primarily raised me, succumbed to Alzheimer’s-related complications seven years ago. And then three years ago my father died at the premature age of 61.

Since then, avoiding its observance has seemed like an empty gesture that only emphasizes one’s isolation from their community. I’d known this for a while: there were only so many times I could drink alone in a half-empty tavern playing 18 holes of Golden Tee Golf before coming to that realization. But it took this string of deaths to get motivated to find an alternative.

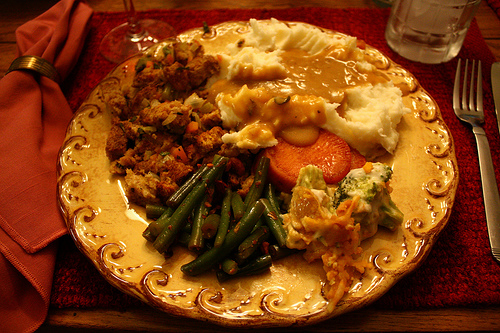

Despite the painful memories it can evoke, I came to realize that the sense of connectedness, forged over a meal you’ve spent the day cooking, is a valuable thing in itself. Despite its baggage, you can wrest Thanksgiving away from its personal and political moorings and use it as an opportunity to share an all-too-rare collective dining experience.

This year, we’ve seen Mutual Aid in Motion.

From scaling sharing hubs to Mutual Aid 101 trainings, we’re helping communities build the tools they need.

Every dollar fuels lasting resilience – proving that when we move together, we all move forward.

In the years since, I’ve come to highly value organizing community dinners with a ragtag group of friends and acquaintances. It’s far more fulfilling than a night at the bar: there is probably nothing so innate to the human collective experience than breaking bread at a table full of food. There are few activities as rewarding as cooking for yourself and others, something that Michael Pollan has described as “soulcraft”. And though the holiday has seriously questionable political implications, it’s rare to have an opportunity where the majority of Americans can take a day off work and spend the day cooking and eating together. Which, for those estranged or otherwise separated from their biological families, can often exacerbate the sense of isolation.

This isn’t for everybody: a few days ago, I spoke with a new acquaintance about her Thanksgiving plans, with the intention of inviting her. She scoffed, saying that she was most likely spending it at a bar. It was clear she had significant negative experiences associated with the day, and I didn’t push her any more. After all, for reasons both personal and political, disavowing Thanksgiving is a completely reasonable reaction. Yet I was struck by how this interaction drew in sharp relief the difference between these different coping mechanisms.

This year, I’ve invited friends over who are similarly separated from their biological families, geographically or emotionally. If you feel similarly isolated, I encourage you to do the same: extend an invitation, put out on your various social networks and see who needs a place to share the holiday. There are other ways to share a communal Thanksgiving: Arianna Davalos’s excellent recent post about how to host a stranger dinner is a great way to go if you’re looking to connect and meet new people. You may want to give to your larger community more directly and help feed those less fortunate; services such as ServeNet and VolunteerMatch are great resources to find such opportunities in your neighborhood. If your concerns are politically-motivated, you might want to connect with people that have similar takes on Thanksgiving and devise education strategies.

I’ve found that any of these collective experiences are a better response than refusing to acknowledge the holiday’s existence: whether connecting with strangers or close friends, these pot-lucks or collective efforts among our self-selected families allow us to connect in a fundamentally human way. A much more fulfilling way to spend an acutely fraught day than many of the alternatives.