Architecture can both dictate, and facilitate, our behaviors. Christopher Alexander’s influential A Pattern Language illustrates the concept best. His book explores the underlying code, or “pattern,” found in our environments. For example:

…Pattern 158 ("Open Stairs") argues for the building of several public outdoor staircases to each upper-story apartment or workplace not simply because they are aesthetically pleasing but because "…we are saying that a centralized entrance, which funnels everyone in a building through it, has in its nature the trappings of control; while the pattern of many open stairs, leading off the public streets, direct to private doors, has in its nature the fact of independence, free comings and goings." —Christopher Alexander, A Pattern Language, p. 742

This year, we’ve seen Mutual Aid in Motion.

From scaling sharing hubs to Mutual Aid 101 trainings, we’re helping communities build the tools they need.

Every dollar fuels lasting resilience – proving that when we move together, we all move forward.

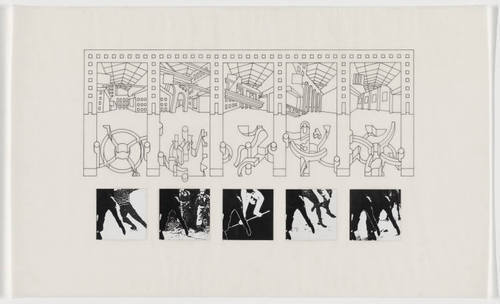

A page from Christopher Alexander's A Pattern Language, above.

Neighborhood sharers live in relatively close proximity: in apartment buildings or condos, dorms, row houses on urban streets or suburban houses on cul-de-sacs. And none of these environments have been designed with resource-sharing or community-building in mind. There’s no underlying “pattern” designed to foster sharing. And since it's hard to work against one’s environment, less sharing goes on as a result.

Many have talked about third places, so called "anchors" of community life that "facilitate and foster broader, more creative interaction." Hallmarks of a true third place, according to the idea's founder Ray Oldenburg, are:

— free or inexpensive food and drink

— highly accessible and proximate for many (walking distance)

— involving regulars – those who habitually congregate there

— welcoming and comfortable

Third places sound a lot like the original British public houses. These Anglo-Saxon environments grew out of domestic dwellings. The "pub" was known as the fifth house because in village tradition in a row of five houses the 5th was the designated public space. It looked exactly like a house, but it housed communal activity. The pub was for the locals to meet and gossip and arrange mutual help within their communities. Then, when rooms and meals started to be offered to travelers gratis, these “pubs” turned into businesses.

Starbucks has co-oped this idea of the third space. Jen Burke Anderson writes here on Shareable about preserving authenticity in public spaces as a result of this type of commercialization of communal life.

I like to imagine we could bring back the idea of an uncommercialized public environment, a neighborhood clubhouse for instance. Or how about The Sunnyside Swap Shop as inspiration:

The Sunnyside Swap Shop and Play Space is an inviting place for families with children 10 and under to play in the Sunnyside neighborhood, a year-round place for member families to exchange useful goods (clothing, toys, books, art supplies, baby equipment, etc.) and a place for parents to network with and support each other. Members bring in items that can be used in the play space or taken home by other families. Children play in the play space supervised by their own family while adults sort through items such as clothes and books that they would like to exchange. Each co-op family takes on responsibility for a certain area or task of the co-op creating a safe, clean, creative, community space. Co-op fees are used to cover the costs of rent, insurance and supplies an also to hire local artists and entertainers to perform in the space.

Or, for something a bit more extreme, how about a foreclosed home as a third place. It sounds radical, but how about this example: In Detroit, Artists Look For Renewal In Foreclosures:

…They set their sights on the foreclosed house down the street — a working class, wood frame, single family house that was listed for sale for $1,900. The house had been trashed by scrappers who stole everything, including the copper plumbing, radiators and electrical lines. Still, they decided to buy it and turn it into what Cope calls the "Power House Project."

"Our idea — instead of putting it all back and connecting to the grid, we wanted to keep it off the grid and get enough solar and wind turbines and batteries to power this house and power the next-door house," Cope says. He thinks he can make the whole place operate "off the grid" for around $60,000, a cost he hopes to help cover with grants. And, since the whole point of the project is to better the neighborhood, Cope wants to turn the first floor of the Power House into a neighborhood art center. The second floor will be a bedroom for visiting artists; Cope believes that if he can just get artists to visit the neighborhood, they'll want to stay. And he hopes the cheap real estate will lure them there.

Imagine if KB Homes added a 5th house, a neighborhood clubhouse, a swap house, a power house, or third place concept to its vast housing tracts. This ‘gift’ to the community would pay for itself many times over in community strength, safety, and so on.

While we wait for the folks at KB Homes to come around (let's start a letter-writing campaign!), how about a DIY approach: there are tons of things we can do this weekend in our neighborhoods. How about sharing storage space, laundry rooms, or amenities like pools or hot tubs with neighbors? Share a yard. Share garages.

What ideas do you have – crazy or practical – that we can do right now to make our physical spaces more condusive to sharing? Anybody seen anything? Send pics!