The most difficult part of starting a new peer-to-peer marketplace is the very beginning. You need to get the critical mass in both the supply and the demand side for the marketplace to really work. This matter has been the subject of some extensive research, but it still remains a difficult nut to crack for many.

After launching Sharetribe, a platform for starting your own peer-to-peer marketplaces (or “tribes”, as we like to call them), we have seen more than 650 marketplaces created. Some of them are successful and thriving, while others are stagnant. This experience has taught us a lot about how to tackle the challenges of creating peer-to-peer marketplaces, specifically in the field of the sharing economy. The purpose of this post is to share what we have learned.

Our definition of a “marketplace” here is pretty wide: It’s an online tool that helps people to communicate with each other about exchanging their real-life assets — the things they own and the skills they have — with other people in a peer-to-peer fashion, with or without using money and without middlemen. It covers everything from a book-lending circle of 10 using a Facebook group to a classified ads site with millions of users. I have tried to distill the ideas that apply to all these cases.

This year, we’ve seen Mutual Aid in Motion.

From scaling sharing hubs to Mutual Aid 101 trainings, we’re helping communities build the tools they need.

Every dollar fuels lasting resilience – proving that when we move together, we all move forward.

1) Focus on the Needs of the People

First, think about this: Who are going to be the members of your marketplace, and what are their needs? Why do you think they need this new marketplace? How does using it fit into their daily routine? Why is your solution better than all the existing ones?

Many people today start designing a marketplace by focusing on a single asset, like a car, an apartment or even a washing machine. While that can be an effective approach, it’s not the only one. Sometimes it’s more effective to start with the needs of an existing community, and enable the members to share multiple, different assets. You might be surprised at the results.

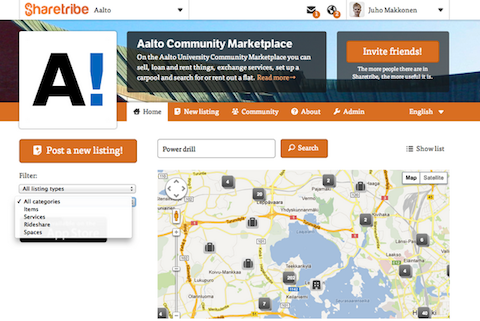

The first marketplace created using Sharetribe was the Aalto University Community Marketplace. Today it has more than 4000 members. We started by interviewing students, who said it would be cool if they could borrow tools from their peers and get help when needed. Thus, the first iteration we launched was focused on lending goods and exchanging services. However, we soon realized that the students also wanted to use the solution for more familiar tasks like selling their course books and looking for apartments, so we enabled them to do so.

We launched a similar marketplace for the neighborhood of Kallio in Helsinki and for the homeowner association of Korso. In the former, the most popular offerer was a guy who was willing to drill holes in the walls of his neighbors for free (or in exchange of a few beers). In the latter, the hit product was horse manure. One resident had a huge pile of it on his yard, so he offered it to others to pick up and use for their gardens.

We’re now designing Sharetribe in a way that makes it really easy for the creators of the marketplaces to adapt to new situations. You can easily change both what is shared (the categories) and how they are shared (lending/renting/swapping/selling/etc), easily adding and removing options on the fly, based on what your community needs. You can start with just one category if you want, and add more when needed.

2) Pick the Right Tools for Creating Trust

As we all know, trust is vital to marketplaces. Different kinds of marketplaces require different tools for creating trust. It depends on the asset that is shared, the type and the size of the community, and cultural differences.

In Aalto University, we started with a completely open community. Everyone could join and post content, and much of the content was also visible to non-registered users. Soon we discovered that while the members trusted their fellow students, it was important for them to make sure that the people they were interacting with really were from the same school. So we introduced an email confirmation: you couldn’t get in without a university email address. However, some folks still wanted their listings to be searchable by anyone. The Finnish people, especially young folks, in general trust strangers. Thus, we allowed the users to choose whether to make their content public (viewable also by non-registered users) or private (visible only to fellow students).

A very different case was the tribe created for the Oakland Single Parents’ Network. The purpose of this marketplace was to help busy, single parents get help from one another in their daily activities.

We soon noticed that this community required very different level of trust. Said one member, “I’m a judge and a single mother of two. There’s no way I’m going to join any online community where someone could track down who I am and where I live.”

We decided to make this marketplace completely private and invite-only. You couldn’t see any content without logging in, and to sign up, you needed an invite from another member. Also, you could follow the “invite chain” all the way up to the founder of the network (the initial member of the tribe), so it would be easy to see how everybody is connected. We also allowed people to be anonymous, if they desired, while in Aalto we required everyone to use their real name.

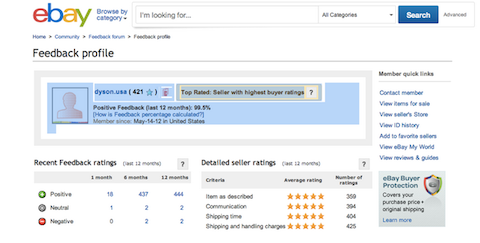

Many marketplaces use a classic rating system to create trust: after a transaction you can rate the other party by giving them thumbs up or a star rating. While these systems are great, they also require some thought. The rule of thumb is that the smaller the size of the marketplace, the less complicated of a system is required. If it’s just a group of 20 people sharing gardening tools, and everyone knows each other, it’s obvious no rating system is required. If it’s a community of 10,000, a simple thumbs up or down will do. If you’re talking about the size of eBay, you probably want to have detailed five star ratings for different areas, like delivery speed, condition, and so on.

Again, our goal with Sharetribe is to offer people the choice. You should be able to use the trust mechanics that your community requires, and change them quickly to adapt to new situations.

Many marketplace sites don’t feel very personal. A typical classified ads site is pretty business-oriented; the goal is to make or save money, and that’s it. While some sites targeted to mass audiences, like Craigslist, don’t necessarily need the community feeling, it can be really helpful, especially in the beginning. If the members feel that there is something special about this particular marketplace, they are far more likely to engage.

The first Sharetribe marketplaces used to feel a lot like, well, marketplaces. In our previous design, the content was up-front, but the people behind the content were pushed to the background. In our latest version we introduced some subtle changes that aim to change that. Along with redesigned profile pages, we introduced a “members view,” which is currently a simple grid of faces and names. One of our users, who had previously complained about his neighborhood marketplace not feeling friendly and warm enough, commented that simply seeing the faces of the other members suddenly made it feel a lot more like a community.

Etsy is a great example of building a community around a marketplace product. They have done it by creating and embracing different ways for their customers to interact with each other. At Sharetribe, we’ll keep adding new ways for people — both the members of a certain marketplace and the creators of the marketplaces — to communicate outside the marketplace context. We talk about our tribes as “community marketplaces” to emphasize this very aspect.

Etsy has managed to build a community around its marketplaces.

4) Decide Who is in Charge

Whether your marketplace is a classified ads site for thousands of people or a book-lending circle of 10, there needs to be someone who’s in charge. Again, this is especially crucial in the beginning. At some point, you might notice the marketplace reaching a critical mass, after which it can start to live a life of its own. However, in the beginning it needs someone who is in charge of enabling the creation of that initial engagement.

One of our users recently complained, “I started a tribe for my neighborhood and nobody joined. How sad.” Many people don’t realize how much work it actually takes to build a successful marketplace from the ground up. There’s a lot of manual work: quality assurance, answering the questions of the first members, building the initial selection, and simply spreading the word. This is the main reason many of our marketplaces have stalled. People get an idea for a marketplace one night, get excited and create it, but then lose interest before they reach the critical mass.

One of the things we want to do with Sharetribe is to make the marketplace creator’s life easier by offering a ready-made set of tools for moderation, customization and communication. There’s still a lot of manual labor you need to do yourself, there’s no question about that, but many parts can and should be automated, and that’s where these tools can be of help.

Sharetribe gives marketplace admins tools to make it easier to curate the community.

5) Start with a Small Group of Committed People

So, you’ve created your marketplace, designed it around the needs of the community, and know who is going to be the community manager. By this point you’re probably anxious to tell the whole world about it. But you shouldn’t just yet.

If people arrive and see an empty marketplace, they’re not going to hop in and start producing content. This is a well known “chicken and egg” problem in two-sided marketplaces: the marketplace is only worth engaging with if there is enough content.

A lot has been written about this issue by others, so instead of delving in too deep, I’ll give just one simple piece of advice: you should “seed” the marketplace by gathering a small group of committed people.

It always helps if you are building the marketplace for a community that includes yourself. In that case you can be the most committed, first user. After that, you should think about those people you can easily reach, who belong to the target group of the marketplace. If the marketplace is for your university, you should contact your fellow students. If it’s for your neighborhood, you should contact the people living next door. If it’s all the people in your country, you might want to start with your Facebook friends.

Some of our tribes have failed precisely because not enough attention has been payed to this issue. This can be especially tricky when working with larger, established organizations which have their own set of rules and hierarchies. Even if you are a big organization and have identified a clear need for an internal marketplace, you can’t just expect that if you put up a site and add a link to your intranet, it’s going to be enough to get things going.

TaskRabbit started by acquiring a list of potential “rabbits” in certain neighborhoods, which made it easier to focus on the people employing the rabbits afterwards.

6) Find the Right Communication Channel(s)

Now you have the initial content in place, and it’s finally time to let everyone know. But how?

It depends. If the marketplace is open to everyone, you want it to go viral. It will help a lot if you make it easy for people to share their content through social media, make a compelling case to invite their friends (“the more people there are in the marketplace, the better it works for everyone!”), spend some time working on SEO so that people looking for a marketplace like yours will find it, and maybe manage to get the media to write about you.

However, there are other things you can do too. Often, the most effective way to spread the word in the beginning is to use existing communication channels. This is especially effective when the marketplace is directed to a specific, smaller audience, like people living in a certain city, or students at a university.

The good old mailing lists still work great. They are the primary tools we have used in multiple, successful, university communities, the most recent example being the University of Helsinki, the biggest university in Finland. Facebook groups or pages that have a lot of followers are also great. The active community of the Kallio neighborhood got its critical mass almost solely from two posts on a popular, local Facebook page.

In the very beginning it’s also good to remember offline channels. It’s not scalable, but it can be effective for reaching the first early adopters. Go to events and talk to people face to face. Offline can be viral too. You can make it easy for people to print out posters and stickers they can then spread around. There’s a lot of creative stuff you can do.

We have failed in the past by not getting access to the right communication channels. One of our cases was a business park that had dozens of companies in it. It wanted to create a marketplace community to bring all the employees of those companies together. However, it didn’t have an existing communication channel that would have quickly reached all those employees, and the critical mass was never achieved.

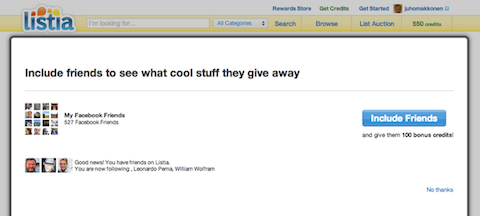

Sometimes a good way to create buzz is to make the marketplace “invite-only” in the beginning. If you manage to brand it correctly, everyone will want an invite and the existing members will be motivated to send the invites, because they know it’s the only way to make the platform useful for them. However, this approach can also backfire. My own neighborhood community marketplace at Lauttasaari was originally invite-only. But then we realized that some of the most effective ways to spread the word about it were posters, local events and the local newspaper. All the people coming to the site from these sources would not have the invitation code and would feel disappointed. Thus, we ended up removing the invitation requirement.

At Sharetribe, we try to build things in a way that makes spreading the word as easy as possible for the people creating the marketplaces. We’ll take care of issues like SEO, social media integration and invitation systems for those who need them, and we’ll also make it easier to produce custom posters and other material.

Listia, a marketplace for free stuff, uses its virtual currency cleverly to incentivise people to invite new users.

Summary

Every marketplace is different, and unique ideas are needed for growing each one. Still, remembering some basic concepts in design, administration and communication can help you get things rolling. Try to find the right niche, make your marketplace feel like a trusted community, put some effort into community management, and take advantage of existing communication channels, and you are lot more likely to succeed.

Additional Resources on Two-Sided Marketplaces

Wikipedia: Two-Sided Markets – a good place to start

Two-Sided Marketplaces – a constantly updating list of blog posts and other online articles discussing challenges related to two-sided marketplaces

Multi-Sided Platforms – Harvard Working Paper by Andrei Hagiu and Julian Wright

Chicken & Egg: competition among intermediation service providers – A classic journal article by Bernard Caillaud and Bruno Jullien

Some Empirical Aspects of Multi-sided Platform Industries – David S Evans does empirical analysis of why c2c platforms like eBay have succeeded

The Economics of E-Commerce: A Strategic Guide to Understanding and Designing the Online Marketplace – a book by Nir Vulkan that covers multiple types of e-commerce

Indebtedness and Reciprocity in Local Online Exchange – Airi Lampinen, Vilma Lehtinen, Coye Cheshire and Emmi Suhonen reveal why people can be reluctant to participate in “share for free” marketplaces because they don’t want to be indebted, using Sharetribe as their use case.