Pandemic stay-at-home orders and social distancing prompted a rapid rethink of our urban streets, with many cities limiting vehicle traffic almost overnight. While many welcomed the increased pedestrian access, anthropologist planner Dr. Destiny Thomas questioned how the decisions were implemented in communities of color, which are the most impacted by the pandemic.

New bike lanes and a network of “slow streets” popped up in cities including Oakland, New York, and Minneapolis, creating space for pedestrians to easily social distance and get around on foot. However, Thomas says the move came without genuine community engagement, and residents and urban planners of color had questions about safety in these public spaces — especially amid protests against over-policing and brutality within Black communities.

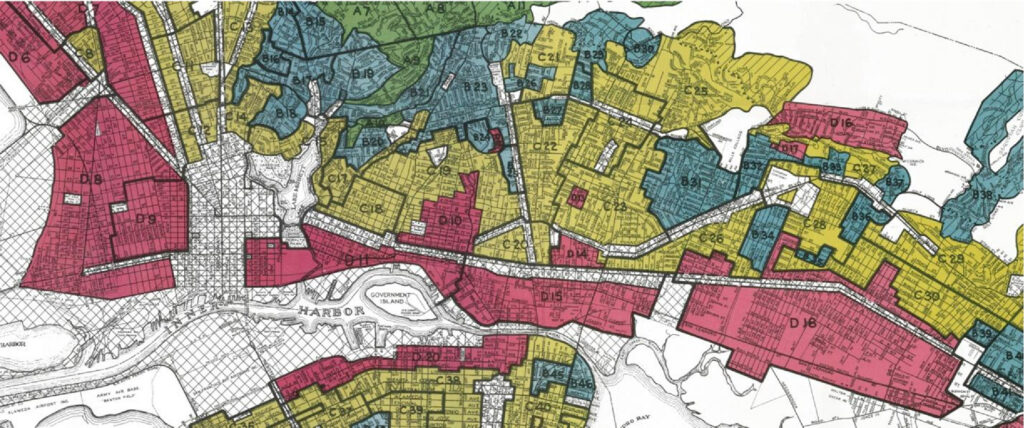

Thomas, a former transportation planner, likened the decision and the implementation process to many of the discriminatory practices that came from redlining, established in 1937 following another national emergency — the Great Depression.

“As with redlining, Black people and many communities of color have been convinced that they don’t belong in the process and have to accept what they are offered,” said Thomas, founder of Los Angeles-based nonprofit Thrivance Group.

For practitioners, community activists, educators, and planners, Thrivance offers educational tools and resources and runs panel discussions to promote sustainable changes in planning processes.

Deemed a far right-leaning practice, redlining impeded homeownership and the building of wealth by restricting where Black families could live. Generations were shut out of the housing market and forced to rent in communities redlined as “risky” prospects for investors, which led to underinvestment in the housing stock, utilities, local economies, and services. Redlined districts were chosen as sites for new freeways, highways, and industrial facilities. These policies combined to disenfranchise and impoverish Black communities and to reinforce segregation. Redlining also has its roots in disinvestment and displacement within communities and has connections to gentrification.

Thomas had one caveat about slow streets: she said they had long been part of a dream progressive agenda among transportation planners to transform urban areas into safe havens for bikers and pedestrians. Closing streets to cars mostly supports those privileged enough to stay at home during these unprecedented times, without consideration of Black, Indigenous, and LatinX people traveling these same streets to get to essential jobs, often in the gig economy. Merge that approach with the legacy of redlining, communities of color continue to be marginalized.

Hugely popular with white urbanites, the slow streets are likely to stay, without a true public process. “This is what I call purplelining,” Thomas said. “And it suggests that anti-blackness and racism are so embedded in planning practices that you really can’t tell who’s doing the harm.”

This is what I call purplelining and it suggests that anti-blackness and racism are so embedded in planning practices that you really can’t tell who’s doing the harm.

Thomas joins a host of planners, architectural designers, and community activists who are shining a light on race and anti-blackness in city planning. Black, Indigenous, and LatinX communities have been disproportionately impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic and economic fallout, which has been compounded by nationwide protests against police brutality.

On June 18-19 2020, Thomas led a live digital 23-hour “teach-in,” titled The Un-Urbanist Assembly, confronting the legacy of anti-blackness in the built environment. More than 8,000 people joined the event to celebrate urban planners of color who’ve been at the forefront of pressing for change, to examine the legacy of racism in city planning, and to discuss toxic urbanism and why planners are culture-bearers.

“I went into this thinking this is my version of protest, and I will use my voice and body to denounce what we know as urbanism,” Thomas said. “When we’re talking about defunding and abolishing systems, let’s talk about what that means for urban planning.”

Thomas told the group that the purplelining in her hometown Oakland — one of the first cities to institute slow streets — matched a redlined map of the city from 1937. “I instantly knew this was a new wave of gentrification,” she said. “I hated to see this happen in my home.”

Resisting purplelining and bringing about healing would “require a degree of reckoning with the past, a plan to heal the existing trauma that stems from the past, and must be careful to resist the tendency to be motivated by and responsive to white comfort,” she said.

That would entail moving away from planning processes that focus solely on what white urbanites want. Cities needed to support and invest more in the economies within communities of color including the street vendors who’ve served as a means for essential items, she said. There should be more focus on long-term planning that redistributes wealth throughout communities and divests from law enforcement and other entities that perpetuate systemic racism. Most of all, the voices of Black, Indigenous, and LatinX communities should be valued and lead the discussions on future planning.

Comfortability and convenience are not sustainable ways for urban planning and design. We should be imagining a world that divorces from our current understanding of what we mean when we say space.

“Comfortability and convenience are not sustainable ways for urban planning and design,” Thomas said. “We should be imagining a world that divorces from our current understanding of what we mean when we say space.”