Editor’s Note:

Shareable is partnering with Tufts University on this special series hosted by professor Julian Agyeman (Co-chair of Shareable’s Board) and Cities@Tufts. Initially designed for Tufts students, faculty, and alumni, the colloquium has been opened up to the public with the support of Shareable, The Kresge Foundation, and Barr Foundation.

Cities@Tufts Lectures explores the impact of urban planning on our communities and the opportunities to design for greater equity and justice.

Register to participate in future Cities@Tufts events here.

Below is the audio, video, and full transcript from a presentation on September 15, 2021, “Rethinking the Future of Housing Worldwide: Favelas as a Sustainable Model” with Theresa Williamson.

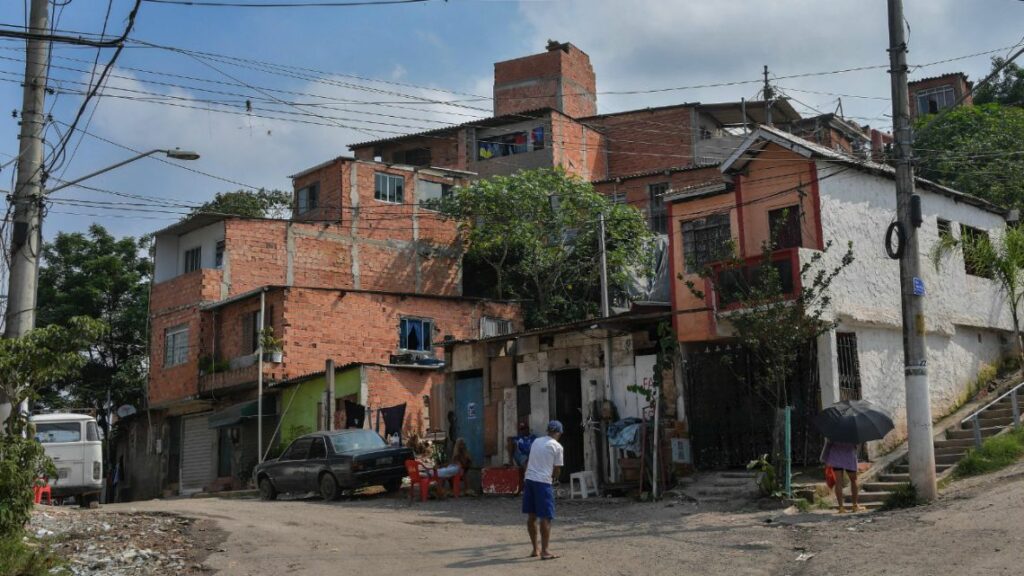

Informal settlements, such as Rio de Janeiro’s favelas, are not new and they’re not rare. Today, one in three people in cities lives in an informal settlement and 85 percent of all housing worldwide is built illegally. By 2050, nearly a third of humanity will live in urban informal settlements.

How can we value informal settlements around the world and integrate them on their own terms into our urban planning practices? Could this search lead to a sustainable urban future? This talk will introduce strategies employed by grassroots NGO Catalytic Communities, in over twenty years supporting Asset-Based Community Development together with Rio de Janeiro favela organizers.

You can find out more information about Theresa Williamson and Catalytic Communities by visiting https://catcomm.org

Listen to “Rethinking the Future of Housing Worldwide” on the Cities@Tufts Podcast (or on the app of your choice):

Watch the video:

“Rethinking the Future of Housing Worldwide” Transcript

Theresa Williamson: [00:00:06] We really need to think about this differently, you know, we have these double standards as urban planners, right? There are all these things that become in vogue: tactical urbanism, hackerspaces, you know, risky playgrounds — many of these are done in favelas and informal settlements organically. They are part of how these communities develop. And if you really think about it, most UNESCO World Heritage sites were established informally. And when you look up why they’re seen as World Heritage sites, you get descriptions like, “Their vernacular urban fabric adapted to the hillsides,” or “Their improvised urban design and unique architecture.” So we really need to drop those double standards and think differently.

Tom Llewellyn: [00:00:49] Could Rio’s favelas offer a sustainable housing model for cities around the world? What are the impacts of over-policing Black mobility in the U.S.? Are $16 tacos leading to gentrification and the emotional, cultural, economic and physical displacement it produces? These are just a few of the questions we’ll be exploring on this season of Cities@Tufts Lectures, a weekly free event series and podcast where we explore the impact of urban planning on our communities and the opportunities to design for greater equity and justice. I’m your host, Tom Llewellyn.

[00:01:20] In addition to this audio, you can watch the video and read the full transcript of this lecture and discussion on shareable.net. And while you’re there, get caught up on all of our past lectures. And now here’s Professor Julian Agyeman, who will welcome you to the Cities@Tufts Fall colloquium and introduce today’s lecturer.

Julian Agyeman: [00:01:46] Welcome to the Cities@Tuftts Colloquium, along with our partners Sharable from San Francisco and the Kresge Foundation. I’m Professor Julian Agyeman and together with my research assistants Perri Sheinbaum and Caitlin McLennan, we organize Cities@Tufts as a cross-disciplinary academic initiative which recognizes Tufts University as a leader in urban studies, urban planning, and sustainability issues. We would like to acknowledge that Tufts University’s Medford campus is located on colonized Wampanoag and Massachusetts traditional territory.

[00:02:21] Today, we are delighted to welcome Dr. Theresa Williamson to be our inaugural colloquium speaker Fall 2021. Theresa is a city planner and founding executive director of Catalytic Communities, CatComm, an NGO that has worked to support Rio de Janeiro’s favelas through asset-based community development since 2000. CatComm producers Rio on Watch, an award-winning local to global favela news platform and facilitates Rio’s Sustainable Favela Network and Favela Community Land Trust program.

[00:02:56] Theresa’s talk today is rethinking the future of housing worldwide favelas as a sustainable model. Theresa, a Zoom-tastic welcome to the Cities@Tufts colloquium as usual, microphones off and send questions either through the Q&A or chat functions. Theresa will talk for about 30 minutes and then obviously we will open up for question and answer. Theresa…

Theresa Williamson: [00:03:22] Thank you, Julian. Thank you all for being here. It’s an honor to be the inaugural speaker. Thanks to Shareable and Cities@Tufts for this opportunity. So today, as Julian said, I’m going to be giving a talk on rethinking the future of housing around the world based on the experiences that we have in Rio de Janeiro, supporting favela organizers for over 20 years now. I run Catalytic Communities, it’s a non-profit organization that I founded in the year 2000 to support grassroots organizers and communities. I’m originally from Rio, but I grew up in Washington, D.C., which is why I sound like this. And then I moved back to Brazil twenty one years ago when I started this work as part of my PhD in urban planning.

[00:04:07] So before we get into the presentation, I’m just going to give you a quick overview. I’m going to show a lot of slides, mostly because I think it’s great when people aren’t familiar with a place to see images — can really paint a picture for you of of what we’re talking about here. I’ll also show some slides with a lot of text, and I may not go through all that text. So what I’ll do is at the end of the presentation, I’ll actually share the link, although you can see it at the bottom there, of this presentation, so you can take a look later if you want to go through the slides in more detail. If you want to catch up with me, you can email me if you want to understand something that I went over more quickly. Okay, but I prefer to include all the slides in the presentation so you can get a sense even if I don’t go through all of them in a lot of detail, okay?

[00:04:54] And so first, before we even talk about favelas and sustainability and housing, we have to understand the context that we’re dealing with, right? Rio’s favelas are not a rarity in the world. We have informal settlements — are pretty much the main way people build housing around the world. A third of people living in cities today live in informal settlements. Eighty-five percent of all housing worldwide is built quote illegally, according to Justin McGuirk and his research. And we can — have we have an option, basically, we can think of these communities as an aberration as we have been thinking about them for a long time. Or we can actually think of them as what they are — people addressing a basic need for shelter and housing in difficult circumstances, but who are at their core trying to address a problem. So favelas really are solutions at their core. But of course, they’re very challenged communities, there are many things that have to be handled, and we really need to rethink our approach and how we see these communities if we’re going to be able to produce better outcomes in cities around the world and build sustainable cities, so at the base of everything we do is an approach that’s asset-based. We look at these communities through an asset-based lens.

[00:06:06] So quickly, I’m going to go through a quick backdrop for those who are not familiar with Rio or Brazilian history. And I think most people, even in Rio, don’t know this. So Rio is actually the largest slave port in world history. We’re talking about one city that received five times more enslaved Africans than the entire United States. And slavery in Brazil lasted 60 percent longer than the U.S. Rio’s favelas are a direct result of this history. The first favela was founded less than a decade after abolition. The city was the federal capital at the time, and the favela is named after a plant. There’s nothing necessarily pejorative about the word favela, it does not translate directly to slum or shantytown. These are simply communities that are developed spontaneously and they’re called favelas after that plant you see in the top right of this slide — a robust spiny resilient bush that existed in the northeast of Brazil in an area that was where the Canudos War took place, which led soldiers to move to Rio seeking the land they had been promised, forming the first community, and naming it after these plants from the hillsides where they had served battle.

[00:07:19] Again, this is one of the slides with a lot of text that I’m just going to quickly go over. Basically, there was very little rural land available. People started moving to cities. They squatted initially on these hillsides and formed the first favelas. And since then, we’ve lived, essentially, a cyclical process of policies of neglect and repression in these communities. Often, we think of neglect as an absence of policy. But in Rio, we see very much that neglect is an active policy. It’s a long history to have passed without sufficient investment and neglect really is a choice by the authorities in these communities. We had a brief window of change which painted a picture of what could be different in Brazil in the late 1980s through the early 2000s. But since then, we’ve had regression.

[00:08:10] So again, a slide I’m not going to go through in a lot of detail, but to summarize that in another way, we’ve seen this cycle of neglect and repression from the authorities. But meanwhile, communities are there. They’re forming. They’re evolving. People are investing. They’re building their homes, they’re rebuilding, they’re forming ties and consolidating their communities. So, the result is today we have about twenty four percent of the city’s population living in favelas and most of these communities, most of the people live in these communities that are over 50 years old. And they’re all over the city. This is a map that depicts just half of Rio, but you can see favelas are in all of the tourist areas. There are around the north zone, the south zone, the reds and oranges. And so they’re really an integral part of the city in the case of Rio. You can see them in the south zone, you can see them in the north zone.

[00:09:08] And going back to their history, essentially, they’re a territorial manifestation of that legacy of slavery. These are communities that serve the city, they build the city, but they’re not seen as deserving of services themselves. So, you’ve got a population that is there to serve and not be served. And when you look at racial maps of Rio, you see that footprint very clearly to this day. Favela communities are Black and Brown and wealthy areas are white. Okay, so this is the backdrop. But then remember how I shared the middle of that slide where people are building and rebuilding? So there’s another part of this story, which is absolutely as critical, if not more, which is while these communities are evolving people or investing in their homes and their communities and they create value in those communities.

[00:09:57] And so what actually defines favelas today are four elements which are universal to all the favelas in Rio, and none of them are necessarily objectively good or bad. They’re just neighborhoods that develop out of need for housing. There’s no outside regulation, so what that means is there’s nobody telling them how to build. That can lead to dysfunction. That can also lead to incredibly creative approaches to urban planning. They’re built by residents for themselves, people create their own — you can see here on the right a community building their own sewage system. People build their own homes. There’s incredible amount of embedded history in these communities where all the bricks, all the tiles have been laid by people and their relatives, their ancestors. And they constantly evolve based on culture, access to resources, jobs, knowledge and the city.

[00:10:48] So a favela in the South Zone will be very different circumstances from North Zone. The South Zone is the tourist area, the North Zone is the post-industrial area. Favelas on hills will be very different from those in low lying areas, Big favelas, small — those who are settled in the sixties versus more recently, the type of leadership they have — all of these things influence the outcome. So these are incredibly diverse communities. More diverse than any formal neighborhoods would be by virtue of that lack of regulation, which again doesn’t necessarily produce dysfunction. It can also produce consolidated, vibrant communities. So favelas again summarized or affordable housing, informal, self-built and unique.

[00:11:34] And they are solution factories. So they start with the issue of shelter, but they go beyond that, right? So, focusing quickly on shelter, I think it’s really important to highlight that in Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, right, we have shelter at the base of the pyramid. We all know this, right, so water, air, shelter. But in the last few decades, in urban planning and urban development in general, we see this conflation of property and shelter, right? So, we think of housing as an investment, as property, not as a basic right, a basic need often. And this is a big problem because twenty percent of people in any major city cannot afford market rate housing. And so it’s not a coincidence that twenty-two to twenty-four percent of people in Rio live in informal settlements in favelas. They’re a natural response to the lack of public or private sector opportunities for shelter. People create their own housing, and that’s what informal settlements are. And there are no different — this problem is not a developing world problem. It is global, right? Los Angeles has 70,000 people living on the streets in tent cities.

[00:12:48] So, you know, as an urban planner, I’ve come to appreciate a host of qualities favelas have organically, for the most part, that we try to develop in our cities. And often it’s hard to retrofit these qualities if they weren’t established in the first place. So, in Rio’s case, affordable housing in central areas, the architecture is responsive. People develop their homes in response to their needs. So this street that you see here on the bottom right, this is in Muzama — everything you see in that picture was built by residents. So when somebody builds their house, right, initially they would have bought just land or a small shack, they’ll build a room, they’ll improve the quality of that over time. They need another room for — their child is born and they add another room. Their child grows up, they might not have floor for them to live with their family. They become unemployed, they might move upstairs and start a shop below. They need leisure space, they might open a terrace on the roof. They need extra income, they might add a floor and rent it out. These are incredibly versatile communities where people create architecture around their needs.

[00:13:55] They are pedestrian oriented right? In Rio’s case, they’re typically near — at least they were founded near employment. This is a huge issue that evictions cause. People are moved far from their employment, but typically favelas form around employment and so on. So, there are a number of qualities, we’ve documented sociocultural assets in these communities, urbanist and economic qualities. This is a study that came out at the end of Brazil’s economic boom period a few years ago. So, it’s not current, but it was really telling because during that boom period, the average wage in favelas increased fifty-five percent in the previous 10 years, which was significantly more than the national average of thirty eight percent. And eighty-one percent of residents like their communities, sixty-six percent wouldn’t like leave their communities, sixty-two percent were proud to live there. And these are statistics that paint a very different picture from the popular misconceptions of these communities, which lead unfortunately to those counterproductive policies I mentioned earlier.

[00:15:00] This is a simple activity we did a few years ago prior to hosting the Rio Olympics. The city was building the Athletes Village, which is this development you see on the right. They were able to get it certified at the time as the first LEED Neighborhood Development Initiative in Latin America. We thought it would be interesting to compare that on the LEED standards to a nearby favela with the help of one of the architects of LEED. And we actually found that the favela had higher indicators on neighborhood pattern and design and location and linkages. So, this is just the kind of thing — just to kind of help flesh out this idea that favelas are not inherently a problem.

[00:15:43] So to go further down that line, let’s look at specific examples. So, this is a community called Vale Encantado, it’s located in the Tijuca Forest above Rio. It’s a community where you see Otávio Alves Barros here, on the bottom left, building a bio-digester for the community sewage system. He’s the president of the co-op in the community. This is a neighborhood that’s trying to become basically a laboratory for sustainability among favelas. They were recognized in this article in The Atlantic a few years ago. They’re about to finish the first full bio system for sewage of a favela in Rio. It’s a small favela, about 40 families, but it’s the idea is to create a prototype for other communities.

[00:16:26] This is an example of the Vidigal, which is a favela that if any of you have been to a favela in Rio, this may well be the favela you visited. It’s in the south zone. It’s next to Leblon, a famous beachside neighborhood. They actually — residents took out 14 tons of trash by hand from this site where the city had demolished buildings, left the debris, it had accumulated trash over years and they were concerned about landslides and other things, and they’ve turned it into this incredible garden oasis. Of course, when it comes to culture, then people are typically more aware of the assets of favelas, whether it’s capoeira, whether it’s samba, whether it’s carnival. Rio’s popular culture is basically rooted in the favelas — maintained or strengthened or developed in the favelas.

[00:17:18] Again, another slide with a lot of text just to provide information, you can look at it later. But essentially, what I’m arguing here is that it’s important to recognize that formal and informal environments in cities, they represent two different ways of life. An informal community is not simply lacking in formality, it’s not lacking in formal instruments. It’s not just about what it doesn’t have. It’s not just about not having land titles or the businesses not being formal or the electric grid not being formal. There’s a lot more to that. So, for example, in the formal city, you have limited complexity because these neighborhoods are regulated. In the informal city, you have growing complexity, which can be an asset in cities. It can help build resilience. You have more financial, monetized — the formal city is more monetized. You have to pay to get things done. In the informal city, many services or demonetized. A lot of support is provided through mutual aid through self-build. There’s a logic of privacy in the formal city and of proximity in the informal city.

[00:18:24] All of these things are important to recognize because when government comes in to formalize informal settlements, they may be unraveling qualities that were developed there. They may be unraveling the social fabric. So it’s very important that any planning that happens in these communities is done very carefully. It’s an ecosystem, like any other, of people, right? A neighborhood, and you have to respect the way people have come to develop their community.

[00:18:51] And on this point of complexity, I just want to show a slide here that looks very confusing if you’re not intimate with the science, which I’m not. But basically, I borrowed this from David Krakauer of the Santa Fe Institute because I thought it was a nice depiction of what happens. Basically, what it shows is as you grow the randomness in a system, any system, you get more complexity to a point. And that complexity can breed resilient systems like an ecosystem, for example, right? The more complexity, the more resilient an ecosystem is. So, he applied the same logic to art just to give a different take and facilitate our understanding. And then I just like to, just as a way to encourage discussion and reflection, apply the same logic to human environments, to urban environments.

[00:19:45] So the simplest complexity and randomness would be like a cul de sac neighborhood, and the most would be a sort of dysfunctional urban environment where things can’t move and so on. But somewhere in between, there’s a sweet spot, and I would actually argue that some informal settlements that have been able to consolidate to a point and reach a healthy level of exchange and some mutual aid and support, development, access to services, could be at that sweet spot. They provide incredibly vibrant environments for people to live, which is why many people in favelas now don’t want to leave their communities if they get the opportunity, they want to stay in their communities and see them improve.

[00:20:30] So here I’m going to show just a few different pictures that show different communities, different favelas in Rio, at different levels in their development with different levels of services, different scales, lack of investment, where residents have to address their needs themselves, the incredibly creative environment that’s created and the ability that people have to sort of take over their street and use their street as a pedestrian zone, primarily. And of course, culture. This is an image of from Providência which is the first favela, it was originally Favela Hill, I mentioned at the beginning, it was called Favela Hill. It was the founding favela of the term. Today, it’s known as Providencia. It’s still a favela, right? It hasn’t received titles fully and been integrated fully in terms of upgrading of services. A few years ago, about a decade ago, the city declared they were going to evict a chunk of the community. A section of the community and the local photographer went ahead and took photographs of the people who were threatened with eviction and plastered them on the sides of their homes as part of a campaign to stop the evictions — and it was successful. So what we found, essentially, is that the favelas where residents take advantage of the qualities of informality, realizing their creative improvements because they can, but also fighting for access to services, they seem to make the greatest inroads over time. So not sitting back and waiting for the government, but also not simply developing informally. So, the combination of developing informally but also constantly seeking government investment.

[00:22:13] So I’m quickly going to talk about our organization Catalytic Communities. So, you get a picture of our project so you can ask questions about these as well. We’ve been around twenty-one years — we just turned twenty-one this week. Our basic model is very simple. We identify people in favelas who are doing incredible work, who are working on behalf of their communities, and we find out what we can do to help. It’s very simple. You don’t need to have a non-profit to do that, but we have created an organization that basically creates a whole resource network of programs and volunteers and access to resources and networks to support those local organizers. So we have four main programs at the moment, but in our early year, and I’ll tell you about those in a second, but in our early years, our focus really was about connecting grassroots organizers to each other through our community center and also through technology — hosting their local solutions in a database online before social media. So, we had a community solutions database which was in Portuguese, English and Spanish at the time, sharing these grassroots solutions. So, all of our work has always been around supporting these grassroots solutions and favelas.

[00:23:21] But then what happened was in the pre-Olympic period, and this is where we became known, we realized that the communities we had been supporting for a decade from 2000 and 2010, were facing eviction, and they were being threatened directly by the government. And a lot of that was based on misunderstandings of what these communities are. And this broad assumption that they have no qualities, they have no value, that they’re better off if they’re removed, they’re better off if they’re relocated to public housing, which is not true typically in Rio anymore because of the quality favelas have attained and also the lack of quality of the public housing and the distance from people’s needs being met. And so on. So, we realized that it was important to do work on the narrative of favelas, and we really focused on that for about six years, working with the international media, working with community journalists, which is a huge movement in Rio and reporting.

[00:24:18] And then now we’ve entered a phase developing models. So our focus now is really about how to actually create sustainable favelas, how to develop these communities sustainably. So, I’ll talk about the four programs we have now. Here we go. So first, as Rio on Watch, which was just alluded to, right, that was our reporting work starting in 2010, which is really about dealing with the narrative of these communities because it’s so counterproductive that it keeps them from developing in the first place, keeps pushing them back because it facilitates counterproductive government programs and it stigmatizes people, makes it hard for them to be served as full citizens, be seen as full citizens.

[00:25:00] The second is the sustainable favela network. And this I’ll talk a little bit more about in a minute because the focus, of course, today is on the sustainable elements of favelas, and this is essentially a broad network of hundreds of grassroots leaders across favelas that are working to develop their communities sustainably. And the third program is the Favela Community Land Trust project. I know some of you at Tufts are familiar with community land trusts. Of course, Dudley Street is a global example that you guys have right there. And we’ve basically been introducing this model in Brazil as an alternative to either keeping favelas untitled or titling them through individual titles because Favela Community Land Trust can protect them against both eviction and gentrification while preserving the assets that we’ve been talking about all along. And then finally, last year we launched the COVID-19 in Favelas Unified Dashboard, which is a crowdsourced data platform where community groups collect data on COVID in their communities and together with other data sources we’ve been able to access, we’ve compiled the most complete picture of the impact of COVID across the favelas.

[00:26:13] So you can see here from this part on the right that these programs they work in sort of a cycle. So, Catalytic Communities, our work began with grassroots organizing support, but we realized when the Olympics came and evictions were happening, that if we didn’t deal with the narrative of these communities, you can only do so much through organizing. It was important to do both. So, we sort of backtracked a bit, started Rio on Watch, and then now we have a cycle that we believe as we move forward in all of these elements, we’re going to be able to really firm and maintain these communities and help develop these communities through their own priorities, right?

[00:26:51] Another slide with lots of text, but I think this one’s really important. So, we operate on an asset-based community development framework. And so what that means is, rather than, like, typical government programs, right? Or even large NGOs sometimes, focusing on a community’s deficiencies — we focus on their assets. Rather than thinking, “Oh, we’re going to solve problems and we’re going to bring in technical solutions,” we identify opportunities based on their assets and then from those we springboard forward to thinking about solutions. We don’t see them as communities deserving of charity or a favor. We see them as communities that deserve investment and have rights. We’re not outside experts bringing in our solutions. We see ourselves as technical allies, engaged in mutual exchange and so on. So, you can kind of go down this list and see that it’s very different the way we approach organizing and supporting grassroots communities and the way they’re typically treated by the government, which is really counterproductive, especially in communities that have so much to offer.

[00:27:55] And now finally, before we conclude, I’m going to highlight the sustainable favela network part of our work. The Sustainable Favela Network started — it was actually seeded in 2012, when Rio hosted the Rio+20 United Nations Conference on the Environment, and we saw in that an opportunity to talk about some of the assets of favelas. And so we put out a call — this is how we do a lot of our work — we put out a call to our community network, you know, “Is anybody interested in talking about their community from a sustainability perspective? Your solutions, your challenges?” And we got 50 responses from 50 community leaders. We identified eight that were very diverse across the city. We went out and filmed whatever it was they wanted to share. And then we patched together, created a film based on those stories. And I highly recommend it, I think it’s a wonderful film. I’m very proud of this project. And that’s going to be almost a decade ago. But the actual network didn’t begin until 2017 because we were so focused on the narrative and our work with media and Rio on Watch in the pre-Olympic build up, and the Olympics were in 2016.

[00:29:06] So in 2017 we mapped this network, we put out a call, again, and we got over 100 community groups that shared what kind of work they’re doing on socio-environmental issues across Rio and reported on this. You can see that most of the projects were — in the bottom right image — you can see that most of the projects were fairly new. So, we weren’t particularly established. So, in the next year after that, we did a whole bunch of exchanges between some of the more established projects, and then we launched the network at the end of 2018. And here are some of the projects and organizations that do the sort of environmental work in Rio — whether it’s stream cleaning, whether it’s working with income generation through adaptive and creative reuse of materials, there are recycling cooperatives.

[00:29:57] This is a music program that uses reclaimed materials to create the instruments. You have solar panels in some favelas. Here’s another. This is a water society — it’s a favela where people organize the water from a source at the top of the community across residents. You have community gardening programs of all sorts — also just individuals who love to garden. This is a green roof project, which is really incredible — the community leader who set this up, they’ve been able to record a temperature difference in his house of 15 degrees Celsius cooler in mid-summer to neighboring homes. So, we’re trying to expand this green roof project. This is a video we did earlier this year about this project that you guys can check out when I share the presentation later. Again, different kinds of gardening projects. This is a project with another favela where a grassroots organizer set up a solar power system to irrigate his garden.

[00:30:59] Then there’s tons of environmental education projects across favelas that do incredible work, and we’ve been reporting on this for the last couple of years. These are, oh, these are the events that we held in 2019, we had about 80 to 100 people at each of these. They were these massive exchanges where basically grassroots organizers from different favelas would all go to one community and learn all about what they were doing there. And they would do trainings and sometimes they would do cleanups. This is one of those events, one of the capacity building circles. This is another event at a recycling facility and graffiti museum. This is a river monitoring project that the graffiti artist who runs the recycling and graffiti museum was doing. This was at our annual event at the end of 2019, which it’s so sad now because we haven’t had in-person events for so long. But we miss it, but we’ve been doing everything online since then. This was our last in-person event of the Sustainable Favela Network in late 2019.

[00:32:03] Now, just before we finish up and go to questions, just want to quickly say the pandemic has exacerbated all of those issues we talked about earlier. Favelas are incredibly at risk, both because of factors like inadequate water and sanitation, people not being able to just take time off from work or work from home to survive. But also things that normally are qualities of favelas, like intergenerational living or a strong social fabric where everyone talks. These are things that actually became a risk factor, but communities have responded. So really, it’s been incredible to watch all of those groups that just mentioned — the pandemic hit, they shifted gears, and they’ve been entirely focused on supporting their neighbors through this difficult time.

[00:32:53] This is a project, for example, that did agroforestry in a favela before the pandemic, and then they switched gears completely during the pandemic, and they’ve been getting agroecological produce to residents to support them to fight food insecurity. This is another project, before the pandemic, they were focused — they basically had this huge space and they did everything they could to support community residents, whether it was tutoring or martial arts or massage or film screening — anything you can think of. And during the pandemic, they just totally switched into a distribution center for goods to help people. So, during the pandemic, everything went online, including the Sustainable Favela Network, which has held a number of public teach ins live events on the pandemic. This is a video you guys can check out later if you want, summarizes all of those events last year. It’s got English subtitles.

[00:33:44] And then finally, before we conclude, there are twenty-six museums in favelas in Rio and memory projects. If you think about informal settlements or what we, you know in English, unfortunately, is often translated as slums, despite their longevity or despite their own experiences. That’s the antithesis of what we think about, right? We think of slums as precarious communities that everyone wants to get out of. Now, if they’re setting up museums and they’re working to preserve their history, then that doesn’t sound like something temporary, does it? And so it’s really important, it’s another kind of demonstration that these communities are here to stay and that it’s important to include them in our development.

[00:34:25] And so to conclude, in the pre-Olympic period, eighty thousand people were evicted from their homes across Rio’s favelas. Many of these were consolidated communities, and we really need to think about this differently. We have these double standards as urban planners, right? There are all these things that become in vogue: tactical urbanism, hackerspaces, you know, risky playgrounds. Many of these are done in favelas and informal settlements organically — they are part of how these communities develop. And if you really think about it, most UNESCO World Heritage sites were established informally. And when you look up why they’re seen as World Heritage sites, you get descriptions like, “Their vernacular urban fabric adapted to the hillsides,” or, “Their improvised urban design and unique architecture.” So, we really need to drop those double standards and think differently. And so I hope that that’s what I brought today — a different perspective.

[00:35:21] Brodwyn Fischer at the University of Chicago, you know, she points out that this is all recent, right? Just think about a few hundred years ago, right, before industrialization, that’s how cities developed. They developed the way we could, whatever we could do with our own hands at our scale. And there weren’t that many rules for how to do it. And we use the materials around us and so on. So that’s really what informal settlements are. They’re just the way people build cities organically. And so the question is what if Rio embraced the unique heritage of these communities and recognized their contributions in ways that supported their development by honoring resident knowledge and history? And what if we invested in decentralized urban planning where communities control their destiny and allies support that vision?

[00:36:08] And then finally, we have — the U.N. predicts a third of humanity will live in urban informal settlements by 2050. So, we need a new approach. What if Rio set that example? We have a lot of things coming up with our organization. I’d rather hear questions from you guys, so I’ll skip through. I’ll mention that we have a digest that we send out every few weeks that compiles all the news on Rio’s favelas in English. It’s a great resource. We put a lot of work into it. Please sign up because it’s free and available. We also take interns, so if you’re interested in that, we welcome you. So looking forward to questions now.

Post-Talk Discussion

Julian Agyeman: [00:36:46] Well, I’m buzzing with thoughts and ideas, what a great way to kick off the Fall Colloquium series. Theresa, thank you. And the chat is buzzing with questions. I’m hoping we can get through them. I’m going to try and go through them in order, although there’s one that I particularly want to get to. So first question: Fascinating presentation. Are there cities and communities in the US that operate with this kind of amazing social capital and autonomy?

Theresa Williamson: [00:37:16] Well, I’m not familiar personally with the informal settlements in the U.S. I do know that they exist. I’ve been told in California there’s some areas where they are, so I don’t know. I mean, I think there are different circumstances. The U.S. is a highly regulated country. Everything here is very different in those terms, and I’ve actually heard planners in the global south say that maybe we should be thinking about cities in two different approaches. And that instead of trying to impose a hyper-regulated structure in those countries, maybe there needs to be space. And I would say that probably some, you know, I don’t know. I feel very personally committed to people determining their own priorities, and I think I wouldn’t say that what’s happening is better or worse than somewhere else, or certainly our problems in Brazil are much more severe in terms of survival on average than they are in the U.S., so it’s hard to say that it’s better, the outcomes there. I don’t know if I’m fully addressing the question.

Julian Agyeman: [00:38:19] I think that’s great Theresa. Question from Josh: How do the programs that CatComm offers engage with the insurgent urban movements such as MTST (The Homeless Workers Movement) in Rio? How do the formal legal organizations like CatComm navigate the legal gray zone, e.g. illegal land occupations to further their goals and vice versa?

Theresa Williamson: [00:38:40] So we work with housing movement — like movements that are dealing with, so, the MTST is a national level organization that supports people living in situations of homelessness, and they help do occupations. And there are a number of groups like that. We’ve been involved a lot with them within the Favela Community Land Trust project, which I didn’t mention as much. And you know, in terms of addressing the grey zone of formal-informal — it’s culturally very different. I mean, we use the formal structure as much as we have to, but we actually very much work as informally as possible in our own activities, and we’re inspired by favelas in terms of how we organize as an organization.

[00:39:23] So, for example, we do as much as we can with as few resources as possible. We try to develop our projects in a way that’s cheap or free so that we can share the strategies that we use as an organization with our community partners. And so we’re not using sort of expensive technologies or depending on expensive labor for anything that we do. It’s an interesting question. I’m trying to think about all the different frames that I could think that through. If you have a specific element that you want to know about, let me know because that might help me focus a bit more.

Julian Agyeman: [00:39:57] All right. Well, I think Josh can follow up with you in due course, Theresa. Valeria asks: As future planners and policy makers, how can we make sure not to overregulate in order to sustain creative hotbeds without communities having been forced into creativity due to neglect? Essentially, how do we sustain, create that sweet spot you mentioned?

Theresa Williamson: [00:40:19] Yeah, no, it’s a good question. So, I have a friend from graduate school who did his research on part of the Brooklyn waterfront, where there was a skate park back in the nineties that was massively revitalized and developed and became more of a private zone. I don’t remember the exact site. I remember talking a lot with him because this is a U.S. case where basically a public site was taken over informally. It was incredibly vibrant. All sorts of folks used it. People came from far away to see it, to be there. And instead of seeing that and the qualities that had been created there and working to embrace that, the government destroyed it. They didn’t see that.

[00:40:59] And so I think that happens everywhere. It’s a problem for cities because what we want is cities that are inclusive, vibrant, diverse. And so I think in a place that’s very regulated, one way to do that is to create, through regulation, create spaces of deregulation — or lack of regulation. Create spaces to just allow those things to happen. And then as planners, my view is that we should be observing those processes and seeing how we can integrate the learning that happens, the organic planning that happens that often will give us ideas for how to make our cities even better. So, I think that’s one thing that can happen. But if there are other questions, I guess I’ll continue…

Julian Agyeman: [00:41:39] Yeah, no, no. The questions are coming thick and fast. Another question from Valeria, and she apologizes for asking two, but I think this is a really, an interesting question that a lot of people are going to want to hear your response to: How do favelas deal with security issues? I’ve often heard of favelas as areas that can be dominated by gang violence. Thus, how do these communities work towards some kind of policing that may be less scary and more in tune with wanting to keep communities safe instead?

Theresa Williamson: [00:42:07] It’s very complicated because the government neglect, you know, really, really over generations facilitated the establishment of these problems, right? And then instead of addressing that neglect, which is what produced a lot of the crime, we continue addressing the final result and doing it harmfully. For example, last year, the Brazilian Supreme Court actually voted in favor of a landmark prohibition on police operations in favelas during the pandemic because they were exacerbating the pandemic. When the police would come in, there would be chaos. Community organizations that were providing relief couldn’t do that, etc., etc. And we actually saw huge decline in mortality in these communities because a lot of it is produced by police and not by gangs. I’m not defending gangs, but we actually have a bigger problem in Rio, which is the militias now than the gangs.

[00:43:05] So in the last decade, these vigilante, off-duty police mafias, which we locally just call militias, they’ve taken over many, many favelas and they now control more of the city than drug traffickers. So the gangs are the police, whether it’s officially or extra-ficially. So, it’s hard. And really what needs to be done is investment in these communities, but on their terms, on their terms. Because what we found also is when the government comes in with their programs and it’s not through community-controlled and community-informed — not just informed but controlled development, it often ends up backfiring, too. And that’s created a really sad situation where we have communities that don’t want investment, sometimes don’t want titles. We’ve had communities where people fight against titling because they don’t want gentrification, and they say that that’s what’s going to happen, right?

[00:44:02] There are communities that are fighting against investment infrastructure because they think it’s going to be the wrong kind of infrastructure, it’s going to cause evictions, or…You know, in the north zone, we have favela Vollmann, where the cable cars were built, and people were removed from their homes in that period before the Olympics — this whole system of cable cars and it was all over the media, all over the world. Well, when the — after the Olympics happened, shortly after, they were all shut down. There are these white elephants floating above everyone’s heads now for the last five years, and the stations have been turned into police stations. So where people had houses, are now, the police occupy them and they keep an eye on the whole community. So, you know, people don’t trust the government. Anyway, it’s very complex.

Julian Agyeman: [00:44:50] Thanks for that. Yeah, that’s really useful answer. Scott asks, well, he says: Thank you. Beautiful talk and ideas. So much to learn as we struggle to solve the housing crisis in the US. I saw permaculture mentioned in one of the slides. Has there been an active permaculture movement in the favelas?

Theresa Williamson: [00:45:07] A little bit, yes. Actually, one of the movements we see the most among the environmental infrastructure movement within favelas is gardening in general. So community gardens, agro-forestry, permaculture, green roofs, different forms. Partly, because I think it’s so accessible and, you know, it helps achieve greater food sovereignty. It’s a very tangible, accessible thing that people can do in their lives right there where they live with fairly low resources. So, we’ve seen a bit of that. And there are a couple of organizations that are sort of the forefront of that. So if any of you are interested, just, you can email me at the email I just shared and tell me what, you know, what you’re interested in and I can share those links with you.

Julian Agyeman: [00:45:52] Great. So our community watch party, the Brown House Classroom, has asked: Has the network made efforts to influence formal infrastructure systems to support favela needs and regional connectivity like transportation, digital resources, sewerage etc.? Any insights about the power for institutional change?

Theresa Williamson: [00:46:11] The Sustainable Favela Network has been on sort of a course of development, which I would say is sort of inspired by and similar to other grassroots movements that have been successful within communities where there’s more of a focus, internally first, to build itself and create trust among members, create a common vision, before kind of going outward facing — before necessarily working with government or so on. And that’s really important. I think the Transition Towns movement has, I think, on their list of how to approach transitioning to a Green community they have I think it’s 8th or 9th or 10th on the order, where they actually engage with the authorities.

[00:46:51] And so it’s been a similar process with us because basically there needs to be this trust. So the first few years I describe with the networking, the solution sharing. Last year, the network began engaging more with the authorities, towards the end of the year, and if any of you are interested, please, I can send you the link, it’s really — it’s an amazing letter. The network put together a commitment letter they sent to all the candidates for city council and mayor with something like 80 different proposals for all these different elements that are worked on by the network, which includes food sovereignty — so it’s community gardens, solar energy, environmental education, income generation, memory and culture, solid waste and so on — water, sewage.

[00:47:35] So there are all these elements that they put in the proposal and ninety-four candidates signed the proposal. And then they put together a debate with the mayoral candidates. And eight mayoral candidates came and it was on Zoom. So, there’s been some engagement with the authorities around implementing some of these ideas. Not many of those folks were elected. So, this year, there’s been another process to try to share more. But I think that’s going to be growing going forward, right? That focus on influencing. The main thing is that, yes, there have been movements towards that. But like I said, it’s a upward battle with getting government. So, the network works along these two lines: one is creating solutions on the ground and not waiting for the authorities. But meanwhile, there’s now a participatory policy front within the network that’s working on how to engage the authorities with these issues.

Julian Agyeman: [00:48:31] And just on that, participatory — I’m thinking of participatory budgeting. Is that involved at all with the favelas? Because if Rio had a participatory budget process, then enough people came from the favelas to vote, surely they could tap into municipal resources?

Theresa Williamson: [00:48:48] That would be wonderful. We have not had participatory budgeting in Rio. It was created in a southern city in Brazil a few decades ago.

Julian Agyeman: [00:48:59] Porto Alegre, yeah?

Theresa Williamson: [00:49:00] Yeah. And it expanded throughout Brazil, there’s other parts of the world who have implemented it, and it’s an incredible model. Basically, you take the discretionary budget of a city and then divide it up by neighborhoods and based on need and population, they determine what they want to use that money for within their local area. And it’s a wonderful, wonderful model. But we’ve never had it in Rio. There’s been a few people trying to pressure for it, but we’ve never made any progress.

Julian Agyeman: [00:49:24] Final question to Danielle: Are community leaders and community members in favelas thinking about climate change?

Theresa Williamson: [00:49:31] Yes, it very much impacts these communities, the ones on hillsides. When it rains, you can get landslides and the ones in the low-lying areas, when it rains, can get flooding. And all favelas are either in one or the other, because favelas tend to occupy the land that no one else is using in the city, and public land, which in the case of the hillsides, were originally occupied by favelas. So, people are talking about it. And actually the Sustainable Favela Network just decided that we’re going to make climate justice the focus for the next year, year and a half. And not just talking about it, but implementing it. I mean, really, what the sustainable favela network does is implement climate justice.

[00:50:11] So yes, we talk about it, folks, grassroots organizers worry about it, but it’s not something that is, you know, people are talking about food sovereignty, they’re talking about — you know, because they need food, food insecurity and therefore food sovereignty. They’re talking about energy, justice and the need for access to energy, they’re talking about access to clean sewage, etc. But those things are an implementation, right? When people act. And so there’s growing recognition of these relationships. But yeah, climate is not at the forefront of people’s thoughts yet because they’re dealing with daily responses to daily needs.

Julian Agyeman: [00:50:47] Well, Theresa, that’s a great point to finish. You have set the standard for this fall. Seriously fantastic, and I am sure you’re going to get a lot of emails from our students. I wouldn’t be surprised if a few don’t ask you about internships as well. It was fantastic. Can we give a UEP round of applause to Theresa, please?

Theresa Williamson: [00:51:12] Thank you, guys. You’re wonderful. Wonderful questions. Amazing.

Julian Agyeman: [00:51:16] Fantastic questions. Yeah. Next week we have Dr. Pascale Joassart-Marcelli of San Diego State, who will be talking about contested geographies of food, ethnicities and gentrification. Thank you and thank you again, Theresa.

Theresa Williamson: [00:51:30] Thank you.

Tom Llewellyn: [00:51:34] We hope you enjoyed this week’s lecture. Join us live for another event tomorrow or listen to the recording right here on the podcast next week. Cities@Tufts Lectures is produced by Tufts University and sharable with support from the Kresge Foundation. Lectures are moderated by Professor Julian Agyeman and organized in partnership with the research assistants Perri Sheinbaum and Caitlin McLennan. “Light without Dark” by Cultivate Beats is our theme song. Robert Raymond is our audio editor. Zanetta Jones manages communications and editorial, and the series is produced and hosted by me, Tom Llewellyn. Please hit subscribe, leave a rating or review wherever you get your podcasts and share it with others so this knowledge can reach people outside of our collective bubbles. That’s it for this week’s show. Here’s a final thought.

Theresa Williamson: [00:52:18] This is all recent, right? Just think about a few hundred years ago, right before industrialization, that’s how cities developed. They developed the way we could, whatever we could do with our own hands at our scale. And there weren’t that many rules for how to do it. And we used the materials around us and so on. So that’s really what informal settlements are — they’re just the way people build cities organically.