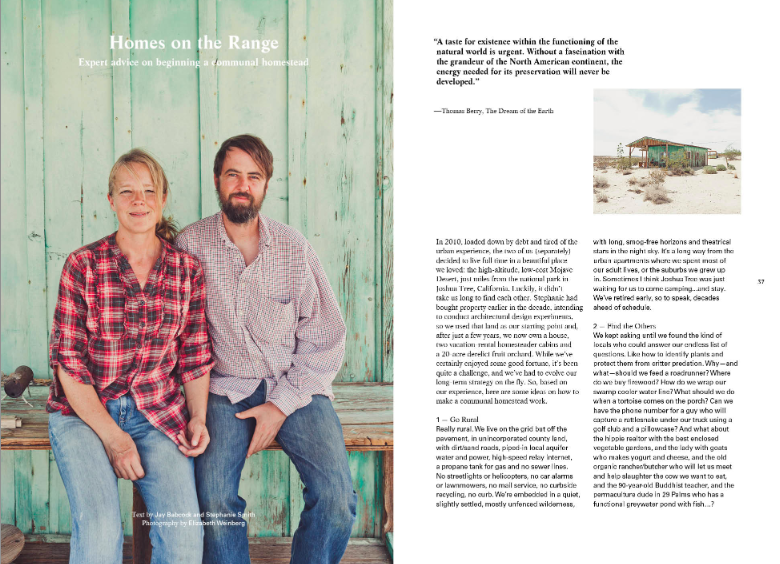

By Stephanie Smith and Jay Babcock, founders of JT Homesteader.

“A taste for existence within the functioning of the natural world is urgent. Without a fascination with the grandeur of the North American continent, the energy needed for its preservation will never be developed.” —Thomas Berry, The Dream of the Earth

Loaded down by debt and tired of the contemporary urban experience, in 2010 the two of us (separately) decided to try our luck dealing with the imploded economy by living full-time in a beautiful place we loved: the high-altitude, low-cost Mojave Desert, just miles from the national park in Joshua Tree, California. Before long we found each other, and today, somehow, we’ve got a house, two vacation rental homesteader cabins (and another on the way) and a 20-acre fruit orchard to our name. Of course, we had a head start — Stephanie is an architectural designer who’d bought property here to experiment on, earlier in the decade — and we’ve enjoyed some good fortune. Still, it’s been quite a challenge, and we’ve had to evolve our long-term strategy on the fly. If you’re curious, here’s how we’ve been making it work out here in the desert — so far…

1. GO RURAL

Really rural. We live on the grid but off the pavement, in unincorporated county land. So: dirt/sand roads, piped-in local aquifer water and power, high-speed relay internet, propane tank for gas, no sewer lines. No streetlights or helicopters, no car alarms or lawnmowers, no mail service, no curbside recycling…no curb. Embedded in slightly settled, mostly unfenced quiet wilderness, with deep unsmogged horizons, enveloped nightly by a fantastically starred sky. It’s a long way from the urban apartments we spent our adult lives in, or the suburbs we grew up in. And yet, Joshua Tree was always here for weekend roadtrips. We went camping…and stayed. We found where we wanted to retire, and moved there early, decades ahead of schedule.

2. FIND THE OTHERS

We just keep asking around until we find the local people who know stuff. What that plant is and how to protect it from critter predation. Why — and what — you should feed a roadrunner. Who to buy firewood from. How to wrap your swamp cooler water line. What kind of snake that is. What to do when a tortoise comes on the porch. The phone number of the gentle guy who will capture the rattlesnake under your truck using a golfclub and pillowcase. The hippie realtor who has the best enclosed vegetable gardens…. The lady with goats who makes yogurt and cheese… The oldtimer organic rancher/butcher who has buffalo on his land, who lets you meet and help slaughter the cow you’re going to eat… The 90-year-old Buddhist teacher… The permaculture dude in 29 Palms who has a functional greywater pond with fish… It never ends.

3. DON’T BUILD FROM SCRATCH

Land is very cheap here, but building from scratch isn’t. And there’s no need, what with all the abandoned or unoccupied homesteader cabins built in the ’40s and ’50s. So, we try to use what’s here already. Rehabilitate existing structures for greater resource efficiency, through adaptive reuse of on-site or locally sourced waste materials. We reduce old structural footprints — converting an RV pad into enclosed, raised vegetable and herb garden beds is a good example. We buy as much land with disused built structures as possible — this permanently ends the risk of irreversible damage from ‘scraping’ (the practice of removing all plants on a site via a single bulldozer swipe) as well as fencing and other destructive/counter-wild ‘development’ by unenlightened owners.

4. PRACTICE MUTUAL AID

Telecommuting gives us some income, and the cost of living here is lower than anywhere else we’ve ever lived. Still, getting out of debt and putting aside money to buy property as it becomes available has at times left us with work that needs doing that we can’t do ourselves, and can’t pay somebody else to do. So we started a group with other local folks to barter/share expertise, labor and tools on each other’s home projects, erecting outhouses and growshacks, building swales to catch rainwater and so on. The group encourages neighborliness, good times conviviality, bioregional solidarity and community resiliency. Only recently have we found out from old-timer neighbors and old Desert Magazine articles that this is the way people have been building stuff out here since the ’40s. For bigger projects, DIY is wasteful; mutual aid is where it’s at.

5. EDENIZE: PLANT SOMETHING

A corner was turned when we added a line item in our monthly budget for new tree purchases. We generate new soil and mulch by composting free horse manure (from a local stable), free woodchips (from a local woodworker) and kitchen waste (from our house — and from our raw food enthusiast neighbor’s), and combining it with the mineral-rich desert sand. Native and climate/terrain-appropriate trees are strategically sited across the acres to provide shade, cooling, aroma, oxygen, habitat for animals and beauty — and to suck up carbon dioxide. We bucket greywater or use a long hose; water comes from an ancient local aquifer. Eventually the trees will send roots deep enough to find rainwater stored in the sub-surface sand. Next up: fruit orchards, blue agave cacti, medicinal plants from neighboring bioregions — gotta re-forest this planet before it’s too late!

6. STEWARDSHIP: PUT EYES ON THE LAND

We leave a significant amount (more than three-quarters) of each property as it is, providing corridor, sanctuary and native habitat for wild animals that travel through the area or live here, including a number of desert tortoises that are older than we are. That means land that is unmachined, unfenced, wild. No lights, as little artificial sound as possible. Our stewardship of this precious space extends to constant, persistent monitoring (rangering?) for illegal and inappropriate human use and damage, with special attention paid to illegal off-road vehicle use, dumping of waste and (this is new) bobcat poachers. Same goes for the Bureau of Land Management land, interwoven across the square miles with private property; the area’s many absent-owner properties; and the Mojave Desert Land Trust’s Wildlife Linkage collection. Only the presence of watchful folks, willing to report illegal activity to the police, can impact creep behavior. We need more eyes on the land.

7. INVITE OTHERS INTO WILD NATURE

This has to do with the Thomas Berry quote above. We rent out our modest cabins using Airbnb at First World-affordable rates. Guests get primary encounters with bright starlight, open land, silence, wildlife, and organized participation in each site’s permaculture cycles. Their urine and feces, collected in dry toilets Stephanie designed, is safely composted over a year, eventually becoming rich soil for new trees. The outdoor showers and indoor kitchen are part of a greywater system; guests’ linen is washed in the main house’s system, also outputting greywater. Meanwhile, guests provide more eyes on the land. We’re enabling meaningful, net-positive impact on the land by non-residents, building a political constituency for land use practices that will bring about a far healthier balance between civilization and what’s left of the wild. And we roll that Airbnb income into acquiring more land.

8. CREATE A COLONY

We’re growing a network of non-adjacent stewarded properties across a single square mile: a distributed colony. Over the decades, we figure each property will be a ‘node’ that triggers affiliated reinhabitation around it — more trees, more bushes, more animals, more insects. More complexity. Less destruction. More life.

9. BEHOLD THE POWER OF A STARRY SKY

Joshua Tree isn’t the only place in North America where you can still be overwhelmed by a moonrise. People are always going to be wowed by a sky of stars. It’s our birthright — we humans can’t help but respond positively to it, it’s in our DNA. So: look for the stars, or some other overwhelming natural/wild feature, buy property there, and steward it wisely. Share it with nature-deprived urban folks via vacation rentals. Everyone wins. Welcome home.

Republished with permission from Wilder Quarterly.