Several US cities are rewriting the rules when it comes to how and where housing can be built. But will it be enough to turn the tide?

A burgeoning zoning reform movement is coalescing across the nation as places like Minneapolis, Denver and Oregon rewrite long-standing laws lifting the stranglehold that single-family zoning has had on urban land use for the last century.

Increased urbanization and a lack of affordable housing are fueling the desire for change, but progress is often held back by entrenched opposition from homeowners and those who bemoan the potential loss of neighborhood character. Can zoning reforms offer enough density to offset a century of race- and class-based housing discrimination?

The reform movement is creating “a new opportunity to be able to rethink cities and rethink urban conditions,” says Scott Demel, director of New York-based Marvel Architects. He predicts that greater density will gradually alter neighborhood character, but residents won’t see radical transformations in the short or long term.

What zoning reform looks like in 2019

Advocates are pushing radical reforms, but most changes to local planning and zoning requirements that have been enacted are incremental.

“When a requirement is changed over time to allow denser housing along traffic corridors and other opportune locations, there are elements that can be baked into the zoning requirements to set up contextual zoning guidelines,” says Demel, such as height and setback requirements, or maintaining continuity by requiring new construction to align with existing street conditions.

“From a design standpoint, it’s really a selection of the architect to interpret those policies,” he adds. “It’s always a balance of what’s there now and what might be there in the future.”

Marvel Architects recently completed The Parkline on Flatbush Ave. in Brooklyn, a 254-unit, mixed-income tower across the street from Prospect Park, an urban expanse designed by famed 19th-century landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted. Its 23-story tower is noticeably taller than neighboring low-rise buildings, but its two-story base with retail and community space creates a significant setback at street level.

Residents filed a lawsuit to stop construction, but a judge lifted a temporary restraining order in 2014 because the park’s east side has no height restrictions. The space had previously been occupied by a medical building and parking lot. “Infill is a pretty standard thing in dense places like New York City, where things are turning over all the time,” Demel says.

In recent years, activism and stark inequality have pushed policymakers into a growing acceptance that land-use laws have kept neighborhoods racially and economically segregated while artificially inflating home prices. In response, updates to zoning laws are clearing a path for denser housing in neighborhoods that were previously preserved for single-family homes. Duplexes beget triplexes, parking structures are making way for mixed-use housing, and some new construction need not even include space for parked cars.

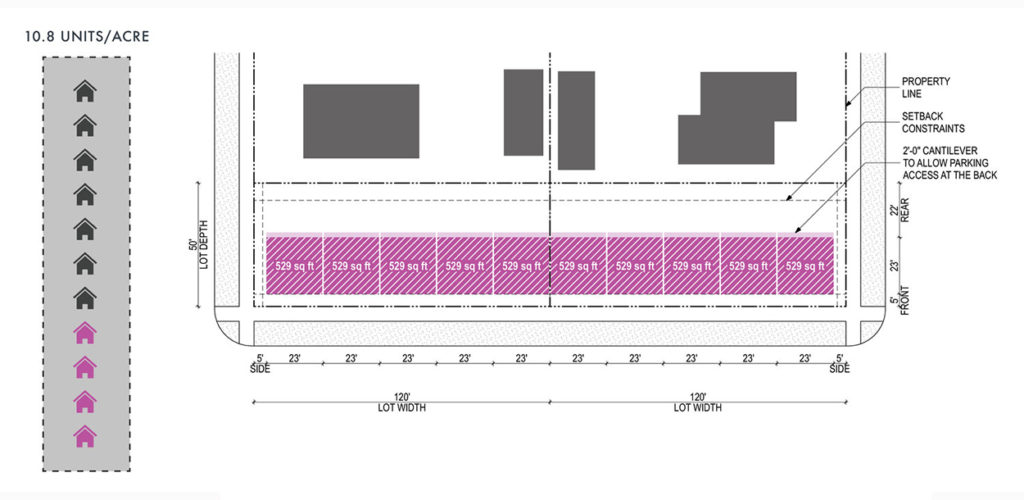

In March 2019, Seattle passed Mandatory Housing Affordability (MHA), a citywide rezoning program that requires developers to build housing for low-income residents and enables greater density. To show how MHA could boost capacity in residential areas, local firm b9 architects developed a case study proposal for adding block-end developments to the backyards of one or multiple homes with empty space in their lots.

If builders aggregated unused space in adjoining backyards at the end of a block, b9 envisioned adding two detached accessory dwelling units, or one full-sized home. Similarly, borrowing unused space from four backyards creates an envelope large enough for two 1,225-square-foot homes. Because Seattle now allows row houses in what were once low-rise multi-family and single-family zones, b9 was able to boost density from 7.1 to 10.8 units per acre in its case study.

Affordable housing shortages driving reform

As urban populations swell, a shortage of affordable housing is forcing out middle- and low-income residents like schoolteachers and retail and health care workers, whose presence is required for a city to operate optimally.

As a result, cities in different parts of the country are retooling local ordinances to address issues that recur in multiple metro areas, including gentrification, homelessness, and the expanding carbon footprints of super-commuting workers who spend ninety minutes or more driving in from exurban communities.

These reforms are also being used to address needs that aren’t specifically housing-related; Washington, D.C., moved to allow corner stores to open in row-house districts to create oases in food deserts; Denver’s neighborhood development plan for boosting density dovetails with the city’s goal of reducing car trips to improve air quality and eliminate traffic fatalities.

Rewriting zoning laws alone isn’t a comprehensive strategy for achieving housing equity, says Kearstin Dischinger, project manager and policy planner at BRIDGE Housing, California’s largest nonprofit developer. Previously, she was a policy manager and community development specialist with the San Francisco Planning Department.

She says even though technocrats like civil engineers and city planners aren’t political actors, anyone who hopes to use recent reforms to add density must first consider hurdles that have political dimensions, like lawsuits, NIMBYism, ballot measures and ad hoc groups.

“Even the laws we have on the books don’t seem to always allow us to do the [land] uses that are permitted by the code,” she says. “It definitely feels like there’s a culture in our city of being shy or afraid of doing something controversial that might create more housing just because of the process we have and the way we deliberate.”

While with SF Planning, Dischinger worked on a local density bonus program intended to spur construction of “missing middle” housing like townhomes, courtyard apartments and live/work spaces. The program relaxed height and density restrictions near transit corridors for developers who designate a portion of the new units as permanently affordable. But even with new opportunities to put up taller, denser homes, Dischinger says uncertainty about San Francisco’s labyrinthine approval process continues to suppress new construction.

Moves to override local zoning controls

Senate Bill 50, a law proposed by California State Senator Scott Wiener (D), would allow statewide zoning guidelines to significantly override most local ordinances.

If passed, Wiener says SB50 would represent the state’s most significant change in land use in over a century. It would supersede local zoning restrictions to allow greater density near public transit lines and by-right construction of fourplexes anywhere in the state, meaning such developments can be built without needing any special permits or variances. “It’s an important change and it’s absolutely necessary if we’re going to solve this housing crisis over time,” he said in an interview.

However, the bill stops short of making changes to the California Environmental Quality Act, (CEQA), which allows individuals to delay development by declaiming a project’s perceived impacts, such as increased shadows, wind, and traffic. A 2015 study found that only 0.7 percent of these complaints triggered a formal environmental review, but they can still slow the pace of new construction.

Wiener’s bill attracted 20 co-authors and sailed through two committees with bipartisan support before it was shelved until 2020 by Sen. Anthony Portantino (D), chair of the Senate Appropriations Committee.

Portantino, who represents La Cañada Flintridge, a city where 89.2 percent of residents own their own home and median income exceeds $156,000/year, described Wiener’s bill as “a well-intentioned effort,” but says it raised “legitimate concerns” about increased gentrification, “historic preservation,” and other “unintended consequences.”

Wiener, who represents San Francisco and its adjoining suburbs, says his bill is backed by an “extraordinary coalition” that includes Gov. Gavin Newsom, environmental groups, homeowners, renters, the state’s Chamber of Commerce, AARP, Habitat for Humanity, and several labor organizations. “We have a real shot at getting it passed next year.”

Zoning reform supporters hail from every part of the spectrum. In June 2019, President Donald Trump signed an executive order establishing the White House Council on Eliminating Barriers to Affordable Housing Development. The council is tasked with reducing “the multitude of overly burdensome regulatory barriers,” though the mix of hurdles cited includes some conservative shibboleths such as energy efficiency requirements and “overly burdensome wetland or environmental regulations.”

What zoning reforms look like

In Minneapolis, Denver and Washington, Dischinger says residents are rebuilding single-family homes to add additional capacity with accessory dwelling units (ADUs) — often known as in-law units — via home additions, backyard cottages and garage conversions. “That is definitely important, although you have to think about the scale of change that needs to happen,” she says. “There’s a risk of us being too incremental now and then paying the price in the future.”

Minneapolis 2040 dramatically expands the potential for new construction citywide. This comprehensive regional development plan eliminates single-family zoning across the 422,000-person city. Consisting of 14 discrete goals intended to “guide the future of the city,” the new zoning plan promotes policies focused on climate change resilience, creating affordable housing and eliminating disparities in health, wealth and public safety.

The Minneapolis plan calls for using prefabricated homes and 3-D printed materials like extruded cement to expand the city’s housing stock. It also aims to accelerate construction of ADUs, facilitate increased housing near mass transit; and allow new forms of “intentional community cluster housing” like tiny homes to accommodate residents who are transitioning out of homelessness.

Dischinger says the first decade after zoning reform will see empty lots and backyards get filled in, but adding ADUs won’t significantly alter the physical context. “I don’t think that you would visually notice all the changes in RH-1 (single-family zoned) areas,” she says. “Maybe if you’re super-observant, you’d notice that a garage door turned into a front door.”

Minneapolis 2040 revisits every facet of city life, down to a freeway remediation plan that aims to reconnect and repurpose swaths of the city that were lost to the interstate highway system in the last century. Given the plan’s potential to transform the city and expand its economy, it’s popular with both democratic socialists and the centrist Brookings Institute, which described it as “the most wonderful plan of the year.”

Once enacted, zoning reforms will create new opportunities for seniors to age in place and may help revitalize commercial districts, since density increases foot traffic. Reducing the number of super-commuters also allows developers to stop converting farmland to housing, but getting more residents to walk and use public transit won’t just reduce emissions, says Demel — density increases social contact, a scarce currency in a smartphone-saturated world.

To prepare for a rezoned future, citizens should ruminate about what they want and need with regard to access to nature, green space, and their desire to interact with each other on a day-to-day basis, Demel says. “It’s that kind of perception that takes some time for people to adjust what their expectation is within any particular space.”

It’s not just zoning that must be reexamined, reform advocates say.

Building a new urban future

“Unchecked greater density could be a problem without adequate planning, thinking through not just the opportunities, but the consequences of not having enough support in place,” Demel adds. If cities want to create sufficient capacity for core requirements like schools, infrastructure and transit, “all of these have to come together at once,” he notes. “It’s not just about adding more square footage; it’s a whole package of city planning and urban planning.”

Wiener predicts that if SB50 passes, California rents will stabilize before they decline. “It may take 10, 15 years to see really significant shifts… and that’s frustrating for people,” he says. “People are hurting right now.”

The nation’s largest state is an example of how hard it is to effect change on a large scale; zoning reform is a popular talking point in California cities, but suburban communities with less diversity, more wealth, and room to sprawl are more entrenched in their opposition.

Even in liberal San Francisco, progressives fight to slow-roll infill developments even when they include below-market-rate housing, citing potential impacts like traffic congestion, historical preservation, and obstructed views. Political candidates may debate each over who’s more pro-housing, Dischinger says, “but that’s at the talking point level, and now you need the cultural shift at the institutional level, and all the policy changes in between.”

Reforming California’s zoning laws is a generational project, says Wiener.

“It’s taken us 50 years of bad policy to get into this crisis. It’s not going to take us 50 years to get out — we can do it a lot shorter than that, but it’s going to take time.”

##

This post is part of our Fall 2019 editorial series on land use and housing policy challenges and solutions. Download our latest FREE ebook based on this series: “How Racism Shaped the Housing Crisis & What We Can Do About It.”

Or take a look at the other articles in the series:

-

- Zoned apart: How the US failed to share land but should start today

- Timeline of 100 years of racist housing policy that created a separate and unequal America

- How pro-density advocates in Minneapolis took on single-family zoning — and won

- Bringing equity to the forefront of urban planning

- How some cities are looking to in-law units to ease the housing crunch and build more diverse neighborhoods

- Segregation By Design author expects political battle between fair housing opponents and proponents

- How to ease the US housing crisis? Import strategic policy from abroad

- Cities at turning point: Will upzoning ease housing inequalities or build on zoning’s racist legacy?

- Author Richard Rothstein calls for new civil rights movement to address housing scarcity and injustice

- 8 must read books on US land use and housing policy