This article originally appeared on Bollier.org and is republished with permission.

For years, I have been the rapporteur for the Aspen Institute’s Information Technology Roundtable conference which, every year, brings together about 25 technologists, venture capitalists, policy wonks, management gurus, and others to discuss topics of breaking concern. The most recent topic was the “power curve” distributions that tend to result on open network platforms.

This is extensively discussed in my just-released report on the conference, Power-Curve Society: The Future of Innovation, Opportunity, and Social Equity in the Emerging Networked Economy. The report notes how a globally networked economy allows greater ease of transactions, but also requires fewer workers at lower pay, which tends to aggravate wealth and income inequality. As I write in the introduction to the report:

Although the new technologies are clearly driving economic growth and higher productivity, the distribution of these benefits is skewed in worrisome ways. Wealth and income distribution no longer resemble a familiar “bell curve” in which the bulk of the wealth accrue to a large middle class. Instead, the networked economy seems to be producing a “power-curve” distribution, sometimes known as a “winner-take-all” economy. A relative few players tend to excel and reap disproportionate benefits while the great mass of the population scrambles for lower-paid, lower-skilled jobs, if they can be found at all. Economic and social insecurity is widespread.

Who holds the key to wealth? Photo credit: Pilisa Connor. Used under Creative Commons license.

The report also looks at Big Data and the coming personal data revolution beneath it that seeks to put individuals, and not companies or governments, at the forefront. Companies in the power-curve economy rely heavily on big databases of personal information to improve their marketing, product design, and corporate strategies. The unanswered question is whether the multiplying reservoirs of personal data will be used to benefit individuals as consumers and citizens, or whether large Internet companies will control and monetize Big Data for their private gain.

You can download a pdf of the report here: https://as.pn/powercurve. Here is an excerpt that describes how the power-curve dynamic works:

A profound change is occurring in both the global and national economies as more commerce migrates to networked platforms. This change is the rise of a power-curve distribution of wealth and income as network platforms reduce the friction that previously impeded economic productivity in the old economy. A power-curve embodies the principle of what is known as a power law distribution, in which a small number of people reap a disproportionate share of the benefits of a market (or other network-based activity) while the bulk of participants receive very modest gains. This is sometimes referred to as a winner-take-all or 80/20 rule, in which 20 percent of the participants reap 80 percent of the gains, and 80 percent of the people receive 20 percent of the gains. Power-curve distributions are entirely predictable in many physical and biological contexts, but they also appear to describe structural inequalities produced on human networks, particularly on the Internet.

The conference devoted a session to this issue as a result of several email exchanges months earlier between Kim Taipale, Founder and Executive Director of the Stilwell Center for Advanced Studies, and Bill Coleman, Partner in the venture capital firm Alsop Louie Partners. The lively exchange was provoked by a March 6, 2011, column by New York Times columnist Paul Krugman about the loss of American jobs to automation and globalization; one response that Krugman urged was a restoration of bargaining power for organized labor.

In reading Krugman’s analysis, Taipale saw evidence of a power-law distribution in the network-based markets that are transforming more and more segments of the U.S. and global economies. Taipale asked: How will power-law distributions affect jobs creation, incomes, and wealth in the future? Will social inequality and instability result if nothing is done about the growing disparities of rewards from the emerging network-based economy?

Below, we excerpt portions of the email dialogue between Taipale and Coleman before recounting how conference participants reacted to the arguments set forth. Taipale’s thesis can be succinctly stated: “The era of bell curve distributions that supported a bulging social middle class is over and we are headed for the power-law distribution of economic opportunities. Education per se is not going to make up the difference.” The kinds of work performed by “information creators, exploiters and decision-makers”—entertainers, artists, CEOs, entrepreneurs, technology architects, etc.—will continue to have a future, said Taipale. But the jobs of information managers who make up the bulk of the upper middle class—lawyers, accountants, programmers—are seriously endangered as new forms of software-based automation and outsourcing accelerate. There will continue to be many low-paid, relatively unskilled working-class jobs as service providers, Taipale argue, but “the spoils from the economy will be increasingly distributed on thepower-law curve.”

This image of Vibrant Data captured by Eric Berlow shows lines of thought from 50 experts each trying to solve "how can we democratize data?" This map allowed Berlow to identify 90 essential challenges to finding a solution then he narrowed it down to four: digital data literacy, trust, open platform for sharing and easy access. Images from Brainvise.

Existing organizational structures are being replaced by platforms or networks, said Taipale. This is significant because it is taking so much friction out of the system, and it is happening faster and faster. In the Industrial Age, when information was managed in analog form—i.e., unstructured and on paper—businesses needed lots of workers in the “middle” to manage information inefficiency, he said. That’s why General Motors had ten layers of management between the shop floor and the executive suite. It was a vast, inefficient, paper-based information sorting and distribution organization that was responsible for creating many “well-paying” middle class jobs. A great many of those jobs have been lost over the past thirty years, replaced first by computers and later by networks that allowed decisionmakers to have greater direct oversight and control over production.

This process is now accelerating as new types of “connecting platforms” and associated apps—iPhone, EC2, YouTube, the cloud infrastructure itself, among others—are deployed. These technologies are lowering interaction costs for collaboration, coordination and market-making. The shift is making markets more efficient, competitive and productive—and in the process, destroying the jobs that have historically sustained the middle class, said Taipale: “The only reason we have the middle class is because it was over-compensated for what it contributed to the system, thanks to the relative inefficiencies of technologies at the time.”

Those inefficiencies could not be automated and outsourced previously—but now they can, said Taipale. And that is introducing more aggressive power-law distributions as participation in network platforms (and thus the value of those platforms) grow. The technology-enabled efficiencies may create greater wealth and broader distributions of it, said Taipale, but not enough to maintain existing middle class standards of living in “high-cost silos” such as the U.S. A key issue here is not just the displacement of middle class jobs but the accelerated rate at which they are being displaced and thus the inability of society and the economy to adapt.

The Industrial Revolution went through a similar transformation, with old jobs destroyed and new ones created. But that transformation occurred over a period of generations, Taipale pointed out. Today, skill sets are becoming obsolete within five years, which means that systemic, disruptive changes are occurring ten times or more in a single generation. Our society is not prepared for this kind of hyper-accelerated pace of change, he said. We simply do not have the policy architectures or social organization to handle it, said Taipale, and no one in the private sector, public sector or emerging social systems are even close to grappling with what these trends imply.

The paradoxical result of network effects, Taipale noted, is that “freedom results in inequality. That is, the more freedom there is in a system, the more unequal the outcomes become.” This is because of the power-law distribution that tends to prevail on open platforms, as wealth flows to the “super-nodes,” a phenomenon sometimes called “preferential attachment.”

In the 20th century economy, wealth and income tended to be allocated broadly to the middle class in the pattern of a classic bell curve. But in the new power-curve economy that appears to be emerging, distributions are scale-free and therefore “there is no characteristic node and the average has no useful meaning.” There is no “representative” member of the whole because distributions are so skewed. For example, even though 90 percent of Americans self-identify as middle class, the mean income in the U.S. is now $63,000, said Taipale—but the median household income (in which there are an equal number of people earning more and earning less than that amount) was $50,054 in 2011. This disparity suggests the mismatch between “average” and actual income distribution; the disproportionate number of lower-wage earners reduces the mean income by a one-third, making “the average” far less meaningful. This polarization of incomes could grow worse in the power-curve economy, Taipale contends.

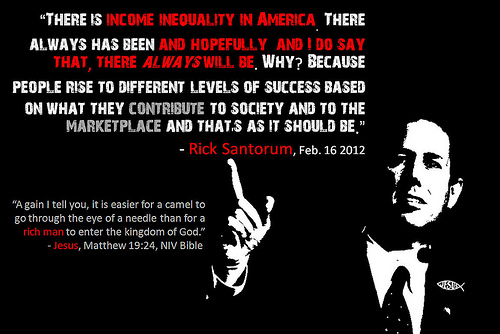

Former Republican presidential candidate Rick Santorum's take on income inequality as contrasted with a Biblical verse. Photo credit: Cory Grenier. Used under Creative Commons license.

Although some observers tout the App Economy as a redemptive force for economic growth and social benefit, Taipale scoffs: “Even if 400,000 ‘new jobs’ are created by hiring app developers, those are not stable, middle class jobs of the sort that previously existed. Companies that would have been hiring Web developers last year are now hiring app developers for a ‘B round’ or ‘C round’ of [venture financing].” The point is that the overall distribution of productivity gains in the networked economy is increasingly subject to power-law distribution and control. Only a relatively small number at the top reap the lion’s share of gains.

In very approximate terms, said Taipale, the bottom 80 percent of app developers are making, say, three percent of the revenues. The mean revenue that a developer reaps from an app is $3,000 a year, but the median is $600 a year. That means that some people are making a huge amount of money, and the rest are not. But the cost of making an app is between $15,000 to $30,000. So what’s making up the difference? asked Taipale. It’s either venture capital money or cross-subsidization [within a company], he said. Taipale’s conclusion from this data is that “the 400,000 jobs that the App Economy is supposedly creating doesn’t necessarily mean long-term, middle class jobs for the economy.”

If power-curve distributions become the norm in the new economy, said Taipale, it could result in greater social polarization and even social disruption. It is not clear what should be done about this trend, however, particularly if it might disrupt productivity and growth. For Taipale, the vexing question is: “How do we redistribute the spoils (or opportunities) to maintain a system in which there is sufficiently widespread prosperity to avoid the problems of political distribution that Krugman proposes in his column, i.e., ‘class struggle’ by politically empowering ‘labor’ to demand its fair share.” Taipale thinks it is a better strategy to focus on devising a suitable economic architecture for fair allocations of wealth and income in the first place, rather than mandate new redistribution schemes, because the latter are far more prone to the vagaries of politics.

As Taipale sees it, there are only a few choices: “Regulate freedom—or redistribute the spoils at the backend, through tax policy. Or do nothing and live with it.” By this formulation, Taipale explained that if governments are going to intervene to address the problem of power-curve distributions, they can either constrain markets and/or the architectural design of technical systems in the first place—which amounts to a regulation of opportunities and freedom—or they can redistribute the spoils of the economy after the fact. Both choices involve some level of political choice, but the latter may be more subject to cronyism and political muscle than the former. In any case, it is inescapable that the power-law curve has social implications. The question is how far can you let those inequalities continue before the social implications become troublesome.

It is dubious to me that this economy or any economy could evade the problems of power-curve distributions through either greater growth or redistributionist government policies.