In 1972, Ernest Callenbach was an editor with the University Press of California in Berkeley, “leading a normal, bourgeois life,” he says. Aside from the occasional peace march, he didn’t participate in the revolutionary turmoil that defined Berkeley in the 60s and 70s. But he was reading and thinking about natural history, conservation, ecology, technology, and Native American culture—threads that came together in a utopian novel he was writing that year that came to be called Ecotopia. A small, cooperatively owned press published it in 1975. A prequel, Ecotopia Emerging, appeared in 1981.

Thirty-five years later, it is difficult to overstate Ecotopia’s quiet, persistent influence on the counterculture, in the form of bioregionalism and locavorism, as well as mainstream professional fields like urban planning and environmental policy—the New York Times calls it "The Novel That Predicted Portland." In imagining that Northern California, Oregon, and Washington broke off from the rest of the United States to form a sustainable, steady-state economy, Ecotopia anticipated real-world developments like compostable plastics, citywide recycling and composting programs, urban agriculture, bikesharing, C-SPAN, reality TV, print-on-demand publishing, and more. It’s sold almost a million copies and been translated into nine languages.

As Scott Slovic of the University of Nevada told the New York Times in a 2008 profile: “People may look at it and say, ‘These are familiar ideas,’ not even quite realizing that Callenbach launched much of our thinking about these things. We’ve absorbed it through osmosis.” Writing in the February edition of Forbes, right-wing journalist Joel Kotkin reviewed Ecotopia’s influence on the real-world urban development of San Francisco, Portland, and Seattle. His conclusion: “The rest of the country may not follow all their strictures, but our would-be Ecotopians could produce some interesting and even usable ideas.”

But in many ways, Ecotopia’s influence is much more complex than simple mimicry; its utopian vision provides today’s counterculture (if such a term is even meaningful these days) with something to rebel against as well as strive towards. As Ernest was writing Ecotopia in 1972, author and urban farmer Novella Carpenter was born. Her parents came directly out of the same Berkeley milieu from which Ecotopia arose—but they were longhaired doers, not bourgeois thinkers, and they quit Berkeley to go “back to the land” in Idaho.

As she describes in the following conversation, growing up in a rural hippie household left Novella permanently disillusioned with the Ecotopian-style ideals that shaped the lives and dreams her parents. And yet she never embraced mainstream culture either, preferring to focus on concrete, hands-on, small-scale projects like the urban farm she started in Oakland, California in 2000. Last year she published a memoir called Farm City: The Education of an Urban Farmer, which has won a slew of honors, become a bestseller, and established Novella as a leading evangelist for urban agriculture.

Last month, I visited Novella’s charmingly scruffy little farm to talk with her and Ernest Callenbach about how Ecotopian ideals have mutated and evolved since the book’s publication, and how a new generation is putting those ideals into practice without necessarily embracing the book. But before we got to those big issues, we needed to discuss sewage and toilets…

Jeremy Adam Smith: Your started writing Ecotopia in the early 70s. What was your life like during that time?

Ernest Callenbach: Well, you know, all my working life I was an editor at the University of California Press but I only worked four days a week so I had a day free and then the weekends to do my writing. I had a house, a wife, two kids, and a garden and a car—

JS: You didn’t have long hair?

EC: No, no, I always looked like a normal sort of a person. It’s like my friend Ted Roszak who wrote sort of the foundational book about the counter-culture [The Making of a Counter Culture, 1968]. He was a professor at Hayward State and he looks like a perfectly ordinary professor. In fact he never went over to the Haight-Ashbury during the heyday of the Summer of Love and all that stuff; he just sat at home and wrote a very good book.

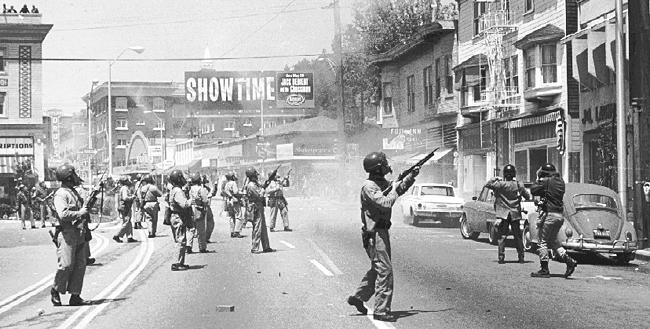

JAS: So you weren’t out at People’s Park throwing Molotov cocktails.

A scene from the battle for People's Park, Berkeley, California, 1969. Credit: Ron Stinnett

A scene from the battle for People's Park, Berkeley, California, 1969. Credit: Ron Stinnett

EC: No, I’m not an agitator or an organizer—I mean, I marched and that kind of stuff and wrote letters and did that, but mostly, I’m like a friend named Fritjof Capra—a very famous writer—who says he is a thinker and a writer. And in my lesser capacity I think of myself the same way. I’m not very practical about organizational matters, actually…

Novella Carpenter (interjects): Mmm, I’m the same way.

EC: I’m not good at managing people or getting groups of people moving all in the same direction—which is a great gift. I once heard an interview with Lech Walesa, the guy who led the Polish solidarity revolution, and somebody said, “How do you do it? What’s your secret to being a leader?” and he says, “Well, you know in every flock of sheep there’s some sheep who gets up in the front and ‘baaahs’ and they all follow, and I am that sheep.” But I’m not. I, Ernest, am not that sheep.

People's Park at peace, Berkeley, California, 2010. Credit: Snoutsparkle

People's Park at peace, Berkeley, California, 2010. Credit: Snoutsparkle

NC: Wait, Ernest, so what books were you editing at the press at that time?

EC: Well, I was basically doing film books because I was editing the journal Film Quarterly at the time. I had founded it in 1958 and then I had run it all those years. After a while I got put in charge of the California Natural History Guide series, all the identification guides of the plants and insects and trees and everything of California. I’m not a natural history expert by any manner or means, but I was an experienced editor so I could keep all these different authors going and….

NC: Is that when The Ohlone Way [a classic study of Native American life in the San Francisco Bay Area] came out too? Around then?

EC: The Ohlone Way came out a little after Ecotopia; I believe about six months [Editor’s note: The book was first published in 1978]. It’s really curious because I think the The Ohlone Way is a classic book—it’s much better written than Ecotopia, for one thing, just in terms of writing, and it was a breathtaking new take on California, a slap in the face to suburban growth, sprawl, all that stuff.

It’s not really known how many Indians lived in California or the Bay Area before white diseases—and white gunfire—came in and began to wipe them out. But it was certainly a large number. That village there at what we now call Emeryville probably had more than 1,000 people in it, and they think California might have had a million people living very dispersed on the land—very small groups with their own languages and very un-warlike, too, that’s the really amazing thing about it.

So there I was in 1971, and my favorite reading matter was Science magazine, the journal of the AAAS. And that came across my desk in the course of my duties at the office so I was able to spend some time thinking about that stuff while being paid by the University Press. And it was good job because it informed me about a lot of different fields that I would never want to become expert in but which helped in writing Ecotopia to know at least a little bit about a whole lot of stuff.

JAS: Ernest, was there a moment when the vision for Ecotopia clicked into place?

EC: There was, and it’s actually a kind of an Ecotopian story because it has to do with sewage—the recycling of sewage.

I had written a book that was originally called Living Poor With Style—it’s been stripped down to a sort of a Woman’s Day level now and it’s not worth reading; people ask me where to find it and I don’t want to tell them although it’s now called Living Cheaply With Style.

But I had written that and I was taking care of my family and my garden and all the usual things and I started work on an article called “The Scandal of Our Sewage.” I had been a country boy in central Pennsylvania, and we had to recycle everything and reuse everything, partly because of the community’s poverty but also because there was nobody to haul stuff away. We buried our garbage in long trenches—sort of a primitive composting system—and we kids straightened nails and saved all the jars and everything else we could find. So I was aware, dimly, that our system of exporting valuable nutrient material through the sewage system was just crazy. It was biologically insane.

JAS: One of many insane behaviors. Why do we do it?

EC: In college I had been a devotee of a philosopher named Alfred Korzybski who talked about “non-survival behavior.” Smoking is a good example of non-survival behavior; it makes people feel good, it’s sort of sexy to look at — the thing is that if you do a lot of it, it’s probably going to kill you. Or at least it’s going to decrease your chances a lot.

And it occurred to me that societies do that too. It isn’t a purely individual thing—societies indulge in non-survival patterns. So I was going to write this article about how we could and should reform our system of wasting sewage nutrients—barging them out to sea, burning them, burying them, you know all that stuff we were doing. And believe it or not, UC Berkeley had a Sanitary Engineering Library. So I began spending time up there and I soon learned that the reason we were not doing that—except for Milwaukee, with its so-called “sewer socialists”—a bunch of German socialists who ran Milwaukee had started doing a thing in about 1921 or something and they still have a product out there called Milorganite, which I don’t think is sold in the West but it’s great for lawns and all but root vegetable uses in the rest of the country.

I discovered that there was this fork in the road where if you took path A it might be the cheapest thing you could do but path B which would be biologically sane, like recycling sewage into fertilizer and reusing it, would cost a little tiny bit more. Therefore in our society where the cash calculation rules, we wouldn’t do it. And I thought, “This is really, really dumb.”

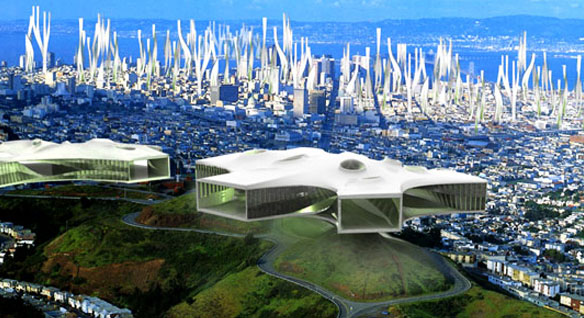

Ecotopia has inspired numerous architects, such as this re-imagining of San Francisco by IwamotoScott Architects, which in 2008 won the History Channel's "City of the Future" competition.

Ecotopia has inspired numerous architects, such as this re-imagining of San Francisco by IwamotoScott Architects, which in 2008 won the History Channel's "City of the Future" competition.

I tried to find a way to write this article in a positive way—here’s how we could do it, here’s how city planners could be convinced it’d be a good idea, and so on and so forth—but finally I started looking around the world to see what other countries might be acting more intelligently about their waste, and I couldn’t find any. Well, the Chinese who were then totally agricultural—their manufacturing base was minuscule—but aside from them nobody, not even the Cubans who had just freshly had a really wonderful (at that time) revolution, they weren’t doing it either.

So a light went on in my head: if a country doesn’t exist that gets its bleep together, maybe it’s time to start thinking about inventing one. And so the first chapter of the book I wrote was about how my narrator Weston goes to the minister of agriculture and he says, “Well, we’re not just talking about agriculture here, we’re talking about the whole system.”

I looked at that for quite a while, as I recall, and I thought “Well, what the hell is this anyway?” It occurred to me that any group of people that did something smart with sewage, that really paid attention to what was going on and how it ought to be dealt with—they would do a lot of other stuff differently: Transportation, land use, residential, the way they lived together, the way they ran their enterprises, the way they did everything.

So, little by little I began doing these bite-sized chunks. All my books have been made out of little tiny bits and the reason is that I was working all the time, so I would only have a three-hour stretch to write something and then maybe not for several more days I wouldn’t get back to the typewriter (as it was then) so I had to do them in little crazy quilt patches and then sew them together later. So that was how it all got started. It all began with sewage, which was altogether appropriate since everything begins with nutrient recycling. I mean, when you get into the deepness of deep ecology—not Arne Naess’s variety, but scientific deep ecology, everything is about nutrient recycling.

NC: Was [the architect] Sim Van der Ryn doing his toilet stuff at that time?

EC: Not yet, I don’t think. They had started building the integral urban house over on Fifth Street in West Berkeley—it might have overlapped with when I was working, I’m not sure. Which was a wonderful, wonderful thing, by the way. Every town needs to have—you’re doing one here, in a way—but every town needs to have one. Theirs was so perfect because you’d drive down the street and it’d look exactly like all those other little bungalows down on Fifth St. in Berkeley but once you went in you realized that it was solar everything and had a really amazing garden and fish pond in the back.

NC: And a composting toilet!

EC: Two or three composting toilets. Did you get to go to it?

NC: No, I never did but I read his book The Toilet Papers. Which is so—have you ever seen that book or read it? It’s so great. It’s a history of the toilet, which is fascinating itself, and then a rant against the idea of using clean water to flush away our feces. It makes no sense! And then there’s a great book, The Humanure Handbook, which talks about ways to make your own composting toilet with buckets and sawdust and that kind of stuff, instead of buying an expensive one.

EC: Yeah. Well, the era I was writing in was still very much under the influence of appropriate technology and I think Sim came out of that background, basically. There is, by the way, a whole book called The Integral Urban House: Self Reliant Living in the City. Complete architectural drawings of everything because—

NC: Yeah, I have it.

EC: You have it?

NC: Yeah.

EC: I don’t have it anymore, but if anyone wanted to replicate it, there are the plans.

NC: And they’re meticulous. You know, there are drawings in the back so you can build everything. It’s really amazing. It’s really, really accurate.

EC: It was a neat place. They would run battalions of school kids through, people would bring them on tours. At the sink faucet there was a thermometer built into the hot water line so they would turn on the hot water and watch the needle go up and then they’d stick their little fingers under the water and “YAI!” because it was really hot. That teaches people—that teaches kids, particularly—that solar power really has power. It was there for, I don’t know, maybe half a dozen years. Something like that.

JAS: Here in the Bay Area there have been a million projects like Novella’s farm, where people are trying to create the world they want to exist in, in these little bubbles. They start urban farms like the one we’re sitting in now, build green homes, start neighborhood work groups, and so on. When you look back on the decades since Ecotopia was published, do you see those kinds of projects influencing the wider culture? Do you think those have been worthwhile?

EC: I try to look at everything biologically, including what human beings do. And you could apply the concept of succession to what’s going on now. The industrial era has laid waste, visibly or invisibly, to huge parts of our society. And in nature what happens when you disturb something, or when there’s a fire or something, first you get really quick-growing little plants that produce a lot of seeds and don’t last very long but they take up the ground; during that time, none of the bigger plants can come in. Then finally you get to the point where the land is hospitable again to whatever was the biggest vegetation there before.

So I think all these little start-ups and stuff—like we’re sitting in one here at the moment—you could say in a way that they’re demonstration projects and they’re very important.

NC: They’re experiments.

EC: Very important experiments. But they’re also the equivalent of what we often call weeds. They’re coming up in battered areas where the regular society doesn’t know what to do anymore and little by little people learn what works and what doesn’t. Like being a farmer in a normal, conventional sense. A lot of the stuff you try doesn’t work. I grew up among farmers and I have an immense respect for practical farmers who are—you can say they are ridiculously conservative but it’s not ridiculous. Their survival depends on being conservative and not doing too many dumb things. Or they’ll starve. So they are very cautious about doing new stuff but that’s the period we’re in now, where we have to try a lot of new stuff. And people do wonderful, wonderful things.

As we talked in her home, Novella plucked seeds out of green coriander. Credit: Jeremy Adam Smith

As we talked in her home, Novella plucked seeds out of green coriander. Credit: Jeremy Adam Smith

NC: I think farmers too are very conservative—I was thinking about this this morning when I was watering—for me, it’s not high-stakes, right? My lettuce crop fails or whatever and it doesn’t matter. I’m not dependent on this. But if you knew, “Okay, it’s up to me to grow all this food,” then you would have a sense of precariousness…you just know too much. You know how these things could fail. So I think there’s a real sense of the power of nature and the things that could go wrong. That’s why I can see how farmers, especially larger farmers, really want to control things and make sure that everything’s going to work out. Otherwise people are going to starve. It’s a big responsibility. And for us we’ve made it so rarified in the Bay Area—we’re so like…organic, whatever, and I think that’s great but at the same time it’s not—food doesn’t have that sort of survival thing anymore, it’s pure pleasure. So it’s really interesting to see how that plays out.

JAS: It seems to be that partially what’s happened since you were working on Ecotopia is we’ve developed this very bifurcated food system, with large-scale industrial farms on one side and a growing number of many small organic and urban farms on the other…

EC: Yes, the number of small farms has gone up a couple hundred thousand in the United States, and they’re real farms. It’s the best piece of news I’ve heard in a long while and these are not people having backyard gardens, these are farmers who are growing something or other—various things usually. Mixed farming is beginning to come back. And even the US Department of Agriculture—which is, God knows, no friend of the small farmer—did a study now I think 15 years ago, where they looked very carefully at mixed farming where you have animals producing manure as well as a variety of plant crops — and they found on 160 acres a farm family could make quite an ordinary decent living out there. This was big news to all the agricultural economists who were thinking along the lines you were talking about. Once the secretary of agriculture—under, was it Nixon, I guess?—Earl Butts, from Utah, said, “Get big or get out”—and that was the mantra that they’ve been living under until very recently. But maybe that’s beginning to give way.

Today, the context is really different because of the economy. As economist Paul Krugman of the New York Times argued, “Let’s face it, we’re in a depression.” It’s not just a recession that’s gonna roll by and everything’s gonna be okay again. This is really a new ball game and so everything — agriculture, urban planning, architecture, transportation, everything — is all going to have to be re-thought. I rather like the work of William Kunstler, who wrote the The Long Emergency. He’s a bit of a madman and in my opinion he collapses the time perspective far too much—he imagines things are going to happen a lot quicker than they probably will. Richard Heinberg [author of The Party's Over, 2003, and Blackout

, 2009, among other books] is also a marvelous, marvelous analyst. They’re both trying to figure out what happens when oil gets more expensive and when therefore doing practically everything gets more expensive.

NC: Yes. We had that experience last summer. Because I have a bio-diesel station and diesel prices were at $5/gallon and so was bio-diesel, and I realized that I was never going to drive anywhere. I would do some calculations, and I’d be like, “Let’s see I could go to East Oakland and go get some burritos” and then I’m like, “Wait, that’s gonna cost me $10 in fuel” — and so I wouldn’t! When it finally happens that we are paying the proper cost for oil, or transportation, people are just going to be staying at home a lot more.

EC: Yeah, localization—I mean, locavore is the first thing that has really gotten into the language, but it’s going to be local everything.

JAS: What do you say to the criticism that high gas prices disproportionally hits poor people or working class people?

EC: Well, it does hit poor people worse but so does everything. Every damn thing that society does hits poor people worse than not-so-poor people—much less the rich. It’s just the way our society’s set up. We’re not probably going to have a genuine revolution of any kind in the foreseeable future so we have to try. In Europe what they do with carbon tax proceeds is to decrease taxes on wages so it’s net-revenue-neutral, as they call it. That means that it’s not raising or lowering the general tax rate but it’s taking some of the burden off working people and putting that burden on the people who use a lot of fuel, mostly. By contrast, these cap and trade systems are very easy to evade. They’re highly political, and in our system which is totally corrupt it would just be a farce, I think. But a carbon tax, you can see the oil coming out of the ground and going in the ships and you can tax it.

NC: Wildly unpopular, though.

EC: It is, and it’ll never happen in our current political system.

NC: This is what is interesting about me in terms of doing urban agriculture, which is kind of hard. People have become so used to everything automated and delivered to them. It’s not even about knowing where your food comes from, it’s like knowing the pain in your back when you’re harvesting stuff. These kinds of things, people are gonna resist because our tendency is to avoid pain at any cost and so these are going to be impossible things to—unless there’s major pressure.

EC: I used to be a lot more optimistic about the human species. We’re reasonably smart compared to the squirrels in my back yard or something—well, I’m not all together positive about that: squirrels are smarter than people think. Random foraging has great advantages, it turns out. But human beings react to real pressures. The mule may have to be hit on the head with the 2×4 but there are lots of 2x4s out there aiming in our direction, so all these people who are so spoiled are going to have to buckle down. It’s easy for me to say that because I grew up in a really, really poor community where the kids got one pair of shoes in the fall and they went through the school year and in the summer they went barefoot because by then their feet had grown bigger and they couldn’t wear the old shoes—and besides they were probably worn out.

But nowadays—you know, like my grandchildren, they have no conception of going without fundamental things. Even quite poor people are living fairly well in this society. And there are many wonderful things about that.

The Berkeley Bowl supermarket in Berkeley, California. Credit: Vera Yu and David Li

The Berkeley Bowl supermarket in Berkeley, California. Credit: Vera Yu and David Li

NC: It’s great! I was just in [the supermarket] Berkeley Bowl yesterday and I was like, “THIS IS AMAZING—” Every time I go there now I’m just like, “I can’t believe I can get five different kinds of quinoa!” You know? People just wandering around like this is normal, like “Oh, this is my birthright.”

JAS: This reminds of a scene from The Simpsons. Bart and Lisa are standing in line for food at a football stadium. Bart says, “Okay, Lisa, if they don’t have tabouli, what’s your second choice?” Lisa sighs as though Bart just said something stupid, and says, “They’ll have tabouli.” [Laughter.]

NEXT: In part two of this conversation with Novella and Ernest, we explore sustainable urban life, the impact of urban agriculture, the Ecotopian promise of the Internet, and how books like Ecotopia are read by younger generations. Read it here.